|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 20(2); 2005 > Article |

|

Abstract

Extramedullary plasmacytoma may originate in any organ, either as a primary tumor or as a facet of systemic multiple myeloma. These solid lesions most commonly affect the upper respiratory tract, gastrointestinal and urogenital tract, skin, and lung. Primary plasmacytoma of the lymph node is a rare hematologic neoplasm, which usually manifests as an enlargement of the cervical lymph nodes with no evidence of any other plasma cell dyscrasia. A 56-year-old man was admitted, due to the presence of multiple palpable masses in the right cervical and submandibular areas. Surgical resection revealed plasmacytoma of the lymph nodes. According to our full work-up, no evidence of the systemic involvement of plasma cell dyscrasia was discovered and thus, the diagnosis of primary plasmacytoma of the lymph node was made. Radiotherapy was administered, and the remnant mass was reduced substantially, to 1×2 cm in size. The patient was scheduled to be monitored by a PET CT scan, as well as by a neck CT scan.

Extramedullary plasmacytoma is a rare form of plasma cell dyscrasia, and represents 1.6~4% of all plasma cell tumors1,2). Extramedullary manifestations of plasma cell dyscrasias may be initially observed in any organ, either as a primary tumor or as a facet of systemic multiple myeloma. These solid lesions most commonly affect the upper respiratory tract, including the nasal cavity, sinuses, oropharynx, salivary glands, and larynx (representing 80% of the reported cases), followed by the gastrointestinal and urogenital tracts, skin, and lung3-5). Most lymph node plasmacytomas are attributable to metastasis from multiple myeloma, or other extramedullary plasmacytomas. Primary lymph node plasmacytoma is quite rare, and represents 2% of all extramedullary plasmacytomas, and only 0.08% of all plasma cell malignant neoplasms1). There have been fewer than 20 reported cases worldwide6). There have been no case reports as yet in Korea. We report a case of primary lymph node plasmacytoma, and include a brief review of the literature.

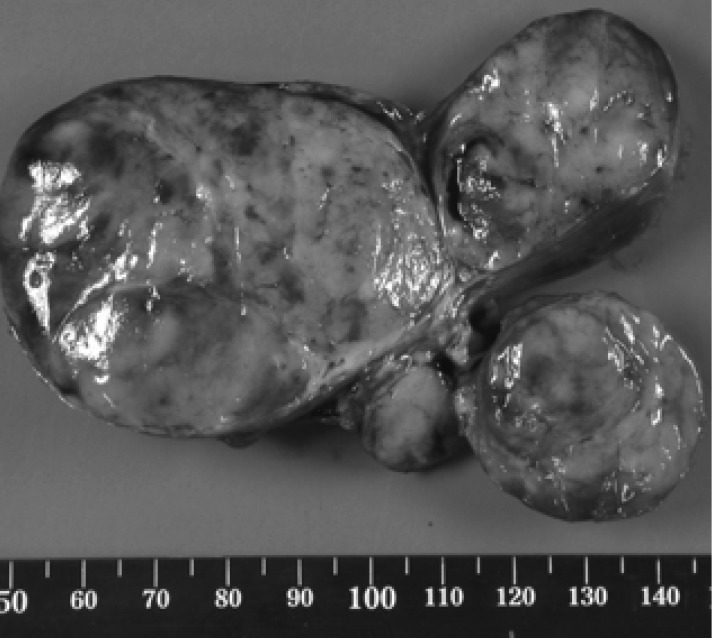

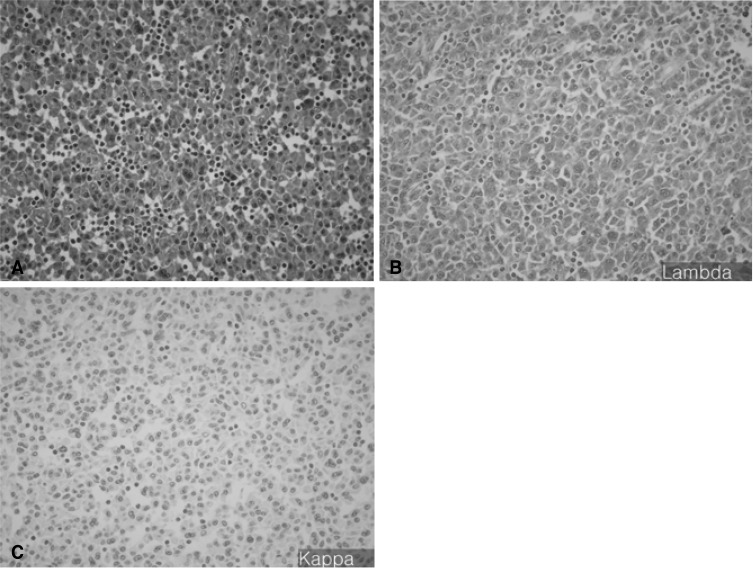

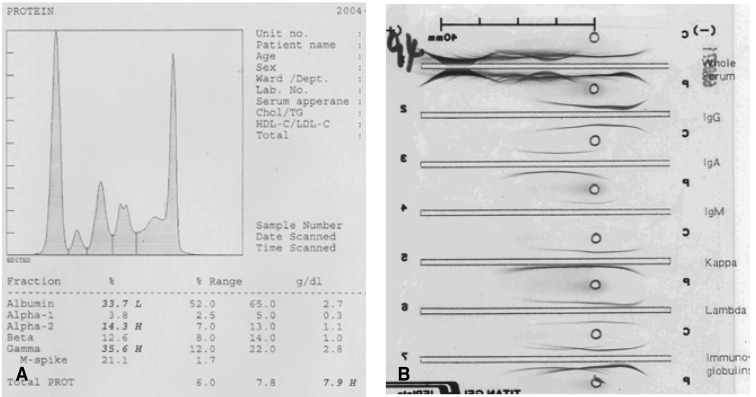

A 56-year-old man was admitted to the otorhinolaryngology department, complaining of multiple palpable masses in the right cervical and submandibular areas, which slowly progressed in size during the past 8 years. The patient had neither any remarkable past medical history, nor a family history relevant to such a complaint. On physical examination, no palpable lymph nodes or masses in any other area of the body were noted. Initial laboratory values revealed mild anemia (Hb 11.6 g/dL), but normal leukocyte and platelet counts. Blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, calcium, inorganic phosphate, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and serum electrolyte levels were found to be normal. Serum albumin was 3.3 g/dL, and total protein was 8.9 g/dL. There were no abnormalities on the routine urine analysis. Neck and paranasal sinus computed tomography (CT) scans were conducted as part of an evaluation for surgical resection. Numerous enlarged lymph nodes were found to be conglomerated in the right submental and submandibular areas (level II, III, IV, V). The largest of these measured about 6.7×4.7 cm, and the right internal jugular vein was appeared to have been severely compressed by multiple enlarged lymph nodes. The tonsil, salivary gland, paranasal sinus, and nasal cavity yielded no abnormal findings (Figure 1). The patient underwent surgery for the removal of the masses, but some small remnant masses persisted. Upon the gross examination of the removed lymph nodes, multiple grayish-white masses were seen, ranging from 2.5×1.8×1.5 cm to 6.5×5×4.5 cm in dimensions. Upon sectioning of the lymph nodes, the cut surfaces were grayish-white with focal hemorrhaging (Figure 2). Histologically, the masses were composed of dense and diffuse infiltrations of atypical plasma cells, with a few residual atrophic lymphoid follicles. These secreted immunoglobulin (Lambda positive) aggregates with extensive amyloid deposits (Congo Red positive, Lambda positive/Kappa negative) in both the stroma and blood vessel walls (Figure 3A -3C). After the operation, the patient was transferred to the hemato-oncologic department, for further evaluation and treatment. A full work-up was conducted in order to ascertain whether there was any other evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia. Serum and urine protein electrophoresis (PEP) and immunoelectrophoresis (IEP) were also conducted. Serum PEP revealed an M-spike in the gamma region, and serum IEP revealed abnormal arcs against anti-IgG and anti-Lambda antisera (Figure 4A, 4B), but urine PEP was not performed due to the small amount of available protein, and urine IEP revealed no abnormal arcs. The β2-microglobulin level was found to be normal (1.6 mg/L), and no osteolytic lesions were noted on the skeletal evaluation, which included a skull series. Rouleux formations were seen on the peripheral blood smear. However, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy from the iliac crest revealed trilineage elements of normal hematopoiesis, as well as no evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia. Accordingly, the patient was diagnosed with primary lymph node plasmacytoma, and was treated via radiotherapy (total dose of 50 Gy in 25 fractions). The residual mass is about 1×2 cm sized, so we are planning to monitor the patient with PET CT scans, as well as a neck CT, in order to assess the viability of the remaining mass.

Most patients with plasma cell neoplasia exhibit a generalized disease upon diagnosis. However, a minority (<5%) of these present either with a single bone lesion (solitary bone plasmacytoma, SBP) or, less commonly, with a soft tissue mass (extramedullary plasmacytoma, SEP)7). Primary plasmacytoma of the lymph nodes is quite rare. In order to diagnose primary plasmacytoma of the lymph nodes, there must be no evidence of plasma cell proliferation elsewhere, and also no associated malignant lymphoma components7). The case reported here was a patient who exhibited a neck mass which revealed, histologically, monoclonal plasma cells in the lymph nodes. However, bone marrow aspiration and biopsies and skeletal studies revealed no evidence of plasma cell proliferation. Also, no evidence of plasma cell dyscrasia involving the upper respiratory tract with the paranasal sinus was detected on the paranasal sinus CT scan. Histologically, primary lymph node plasmacytoma needs to be differentiated from MALT (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) type low-grade lymphoma8). MALT type low-grade lymphoma is characterized by the benign reactive proliferation of lymphoid follicles around malignant cells, and is also distinguished by its characteristic lymphoepithelial lesions. In this case, the fact that there were no such findings, and that the lymph node, histologically, revealed only immature or plasmablastic plasma cells, made it possible to differentiate it from MALT type low-grade lymphoma. Primary lymph node plasmacytoma is a rare hematologic neoplasm, which normally manifests as an enlargement of the cervical lymph nodes. Also, the lymph node is normally replaced by mature plasma cells8). Solitary extramedullary plasmacytomas are highly radiosensitive tumors, and with even moderate doses of radiotherapy, local control rates have been reported to be as high as 80~100%9-11). Due to the small number of patient cases and low local failure rates associated with this condition, the dose-response relationship remains unclear. However, the optimal radiation dose appears to be somewhere within in the range of 40-50 Gy7). Tumors of less than 5 cm in diameter have an excellent chance of being locally controlled with doses of radiation in the region of 40 Gy in 20 fractions, whereas there is a higher risk of local failure when dealing with tumors greater than 5 cm in diameter, which require a higher dose, somewhere in the region of 50 Gy in 25 fractions7,11-13). Surgery is not generally required for diagnosis. Radical surgery is not normally indicated for curative therapy, as the tumors are generally highly radiosensitive, and the majority of patients can be cured by radiotherapy7). In our patient, the tumor size was greater than 5 cm. Therefore, we removed the masses surgically, both for cosmetic reasons and histological diagnosis. After surgically removing the bulky masses, we administered 50 Gy of radiation in 25 fractions for curative therapy. Very rarely, primary lymph node plasmacytoma as associated with focal amyloid depositions8). In this case, the plasmacytoma secreted immunoglobulin (Lambda +) aggregates, as extensive amyloid deposits (Congored +, Lambda +/Kappa -) in both the stroma and blood vessel walls. Primary lymph node plasmacytoma may present as disseminated lymphadenopathy, but does not progress to multiple myeloma. The survival time associated with this condition is significantly longer than that of patients with multiple myeloma8). However, in our case, the patient's tumor was composed of multiple, bulky masses, and continuous follow-up remains necessary.

References

1. Woodruff RK, Whittle JM, Malpas JS. Solitary plasmacytoma: I. extramedullary soft tissue plasmacytoma. Cancer 1979;43:2340–2343PMID : 455224.

2. Pantelidou D, Tsatalas C, Margaritis D, Karayiannakis AJ, Kaloutsi V, Spanoudakis E, Katsilieris I, Chatzipaschalis E, Sivridis E, Bourikas G. Extramedullary plasmacytoma: report of two cases with uncommon presentation. Ann Hematol 2005;84:188–191PMID : 15042315.

3. Alexiou C, Kau RJ, Dietzfelbinger H, Kremer M, Spiess JC, Schratzenstaller B, Arnold W. Extramedullary plasmacytoma: tumor occurrence and therapeutic concepts. Cancer 1999;85:2305–2314PMID : 10357398.

4. Wiltshaw E. The natural history of extramedullary plasmacytoma and its relation to solitary myeloma of bone and myelomatosis. Medicine 1976;55:217–238PMID : 1272069.

5. Galieni P, Cavo M, Pulsoni A, Avvisati G, Bigazzi C, Neri S, Caliceti U, Benni M, Ronconi S, Lauria F. Clinical outcome of extramedullary plasmacytoma. Haematologica 2000;85:47–51PMID : 10629591.

6. Lin BT, Weiss LM. Primary plasmacytoma of lymph nodes. Hum Pathol 1997;28:1083–1090PMID : 9308734.

7. Soutar R, Lucraft H, Jackson G, Reece A, Bird J, Low E, Samson D. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of solitary plasmacytoma of bone and solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma. Br J Haematol 2004;124:717–726PMID : 15009059.

8. Menke DM, Horny HP, Griesser H, Tiemann M, Katzmann JA, Kaiserling E, Parwaresch R, Kyle RA. Primary lymph node plasmacytomas (plasmacytic lymphomas). Am J Clin Pathol 2001;115:119–126PMID : 11190797.

9. Mayr NA, Wen BC, Hussey DH, Burns CP, Staples JJ, Doornbos JF, Vigliotti AP. The role of radiation therapy in the treatment of solitary plasmacytomas. Radiother Oncol 1990;17:293–303PMID : 2343147.

10. Bolek TW, Marcus RB, Mendenhall NP. Solitary plasmacytoma of bone and soft tissue. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996;36:329–333PMID : 8892456.

11. Jyothirmayi R, Gangadharan VP, Nair MK, Rajan B. Radiotherapy in the treatment of solitary plasmacytoma. Br J Radiol 1997;70:511–516PMID : 9227234.

Figure 1

Neck and PNS CT scans reveal that numerous enlarged lymph nodes had conglomerated in the right submental and submandibular areas, and that the right internal jugular vein was severely compressed by multiple enlarged lymph nodes.

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Primary Pulmonary Plasmacytoma Presenting as Multiple Lung Nodules2012 March;27(1)

A Case of Green Urine after Ingestion of Herbicides2008 March;23(1)

A Case of Granular Cell Tumor of the Trachea2007 June;22(2)

A Case of Primary Pancreatic Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma2006 June;21(2)

A Case of Extramedullary Plasmacytoma Arising from the Posterior Mediastinum2005 June;20(2)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print