INTRODUCTION

Tuberculosis of the stomach is quite rare, both as a primary or secondary infection1, 2). It can present as a facet of a multiorgan disease process or may result from immunodeficiency. Clinically, this condition resembles peptic ulcer disease, and in rare cases, can mimic malignancy3, 4).

Here, we report a case of gastric tuberculosis which morphologically mimicked advanced gastric cancer in an immunocompetent patient.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old male presented to the emergency room after 2 days of hematemesis and melena at volumes of approximately 300 cc. He had experienced epigastric pain and nausea for the last several days, but no other symptoms, including weight loss, were evident.

The patient had no past or family history of tuberculosis. He was a 16 pack-per-year-smoker, but was not a heavy drinker. He had lived in Seoul, where he was employed as an electrician. His physical examination proved unremarkable, revealing no lymphadenopathy and normal pulmonary findings. The abdomen of the patient was soft and was not tender, and a digital rectal examination revealed no blood. He had a normal body temperature, and exhibited stable vital signs. Laboratory data recorded a hemoglobin level of 10.6 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 9,400/mm3, platelet count of 185,000/mm3, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 2 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein < 0.8 mg/dL. Liver and renal function tests revealed normal findings. Tests for the viral markers of hepatitis and HIV were both negative.

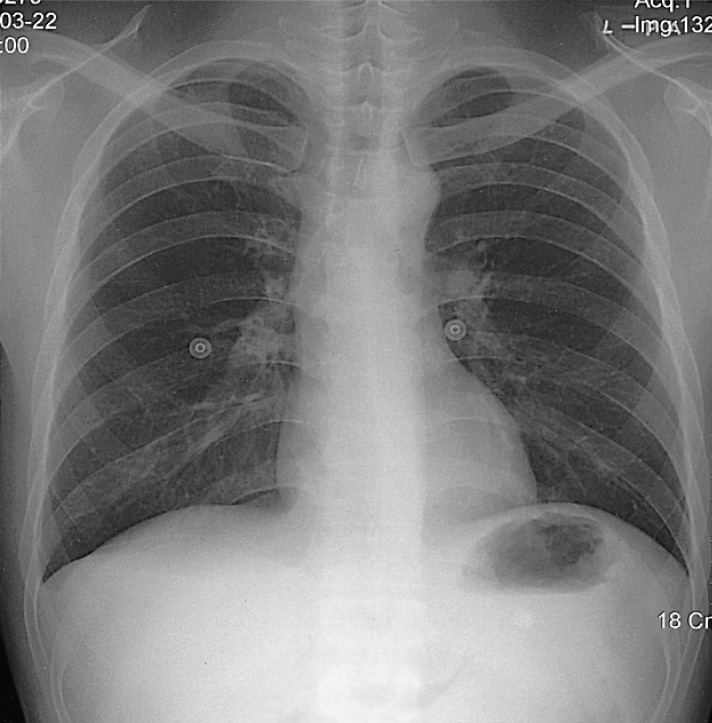

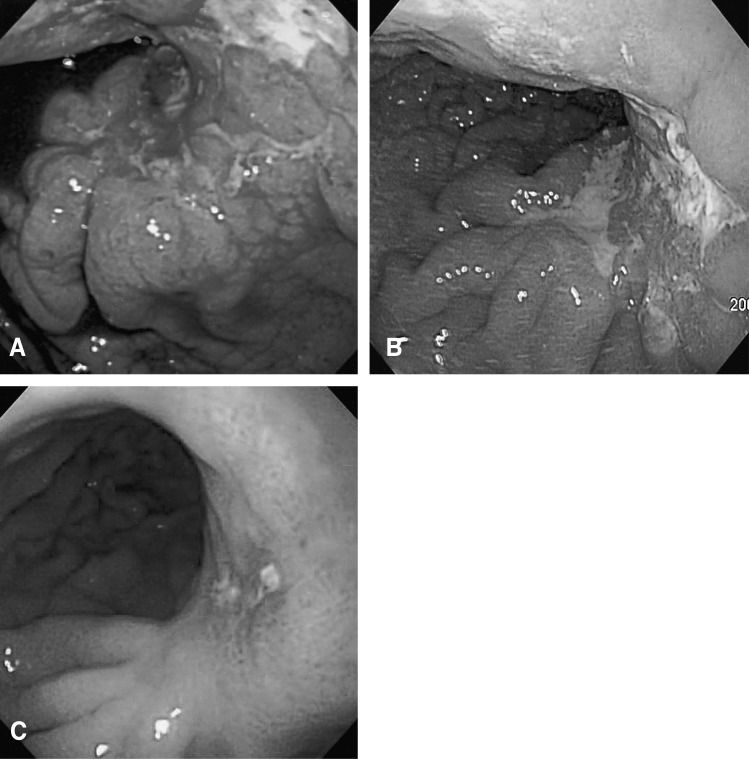

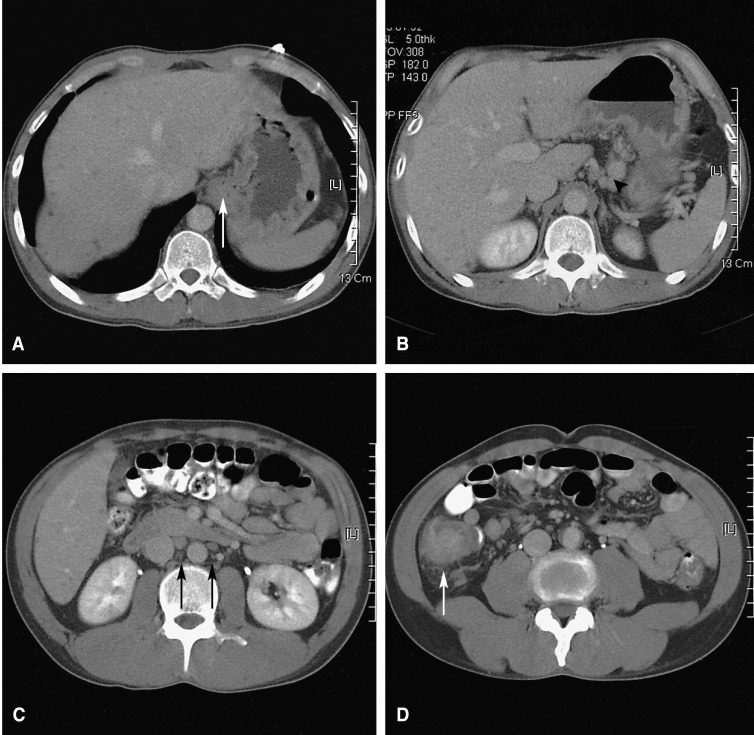

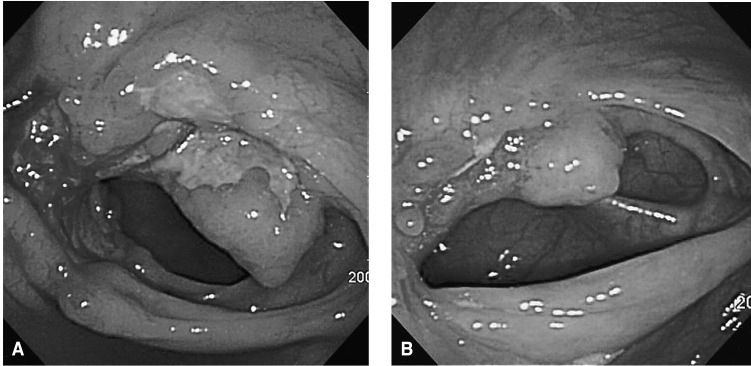

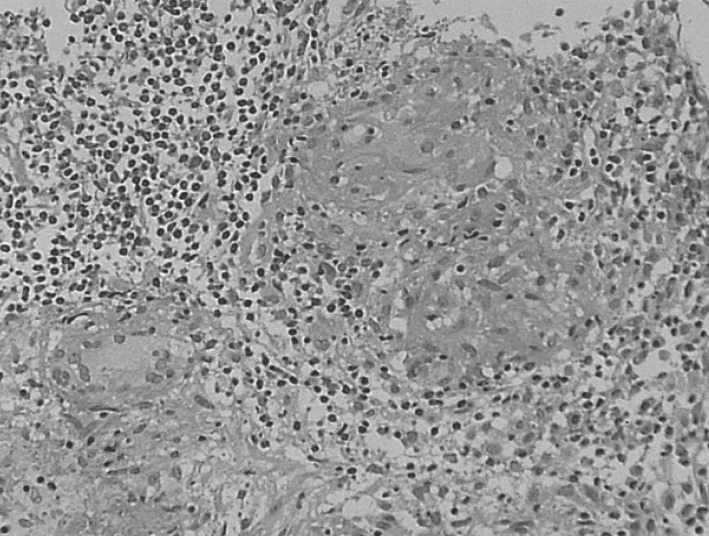

The chest X-ray revealed no pathologic findings (Figure 1). Gastroscopic findings on admission revealed a large, ulceroinfiltrative mass with irregular margins on the posterior wall of the high body (Figure 2A). Blood clots and exposed vessels as recently bleeding stigmata were observed. Additionally, converging and disrupted thickened folds were observed on the surrounding mucosa. Secondary gastroscopy after two days showed more prominent abnormalities of the marginal folds as cut, bitten, and converging shapes, although the clots and vessels had disappeared (Figure 2B). The bases of the irregular ulcers were uneven. These findings strongly suggested gastric malignancy. Consequently, biopsies were obtained from the described areas. A CT scan of the abdomen was conducted in order to rule out other malignant metastatic lesions. The CT scan revealed a thickening of the gastric upper body (Figure 3A) with enlargement of the perigastric (Figure 3B) and paraaortic lymph nodes (Figure 3C). The CT scan also revealed a mass lesion at the cecum and the ascending colon with pericolic fat infiltration and regional lymphadenopathies (Figure 3D). Colonoscopic examination revealed an ulceroinfiltrative lesion encircling the lumen of the ascending colon, through which the scope was unable to pass (Figure 4A). Endoscopic biopsies from the stomach and colon revealed noncaseating granulomas with no malignant cells, and detected no acid-fast bacilli (Figure 5). However, the PCR tests for the detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from gastric and colonic biopsy specimens were positive. No culture tests were performed.

As the patient exhibited no more bleeding, he was treated conservatively, with antituberculous medications of isoniazide 400 mg, rifampicin 600 mg, ethambutol 800 mg, and pyrizinamide 1.5 g daily, beginning nine days after admission. On the follow-up endoscopic examinations, two and eight months after the start of this treatment, marked improvements were observed in the ulcerations with distortion of the mucosal folds at the high body of the stomach (Figure 2C) and in the ascending colon (Figure 4B), respectively. On the CT scan performed after eight months of treatment, the previous lymphadenopathies were improved, and no more wall thickness was seen in the gastric and colonic areas. The patient is currently doing well, and antituberculosis treatment is being maintained with no side effects.

DISCUSSION

Pulmonary tuberculosis is primarily seen in developing countries, in which poor sanitation contributes to its spread. In the 1980s, however, the incidence of extrapulmonary tuberculosis began to increase even in developed countries, with a rise in the numbers of patients considered to be high risk for this disease. This high risk group includes HIV-infected individuals, immigrants from endemic areas, and immunosuppressed patients with transplantations, or who are undergoing prolonged steroid therapy5, 6). Other groups at high risk include alcohol abusers, injection drug users, elderly persons, and diabetic patients7).

Tuberculosis may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, but it most commonly involves the terminal ileum and ileocaecal region, followed by the ascending colon, jejunum, appendix, duodenum, stomach, and rectosigmoid colon2). Isolated gastric tuberculosis, without evidence of pulmonary or other gastrointestinal involvement, is extremely rare, even in parts of the world where intestinal tuberculosis is common, and is almost always located in the antrum or prepyloric region. Gastric tuberculosis normally occurs secondarily to pulmonary tuberculosis or another organic infection1, 8). The incidence of gastric tuberculosis, whether as a primary or secondary infection, is found in only 0.03 to 0.21% of all routine autopsies, and in 0.3 to 2.3% of autopsies of patients with known concurrent pulmonary tuberculosis1, 2). In our case, the patient showed no evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis infection, and showed multiple intraabdominal lymphadenopathies, as well as tuberculous colitis. This is not surprising, as less than half of all patients with abdominal tuberculosis exhibit associated pulmonary disease7), and in one study, the proportion was only 19%9, 10).

The relative rarity of gastric tuberculosis can be attributed to the bactericidal properties of gastric acid, the scarcity of lymphoid tissue in the gastric wall, and the continuous motor activity of the stomach1). It has been postulated that the main causes of isolated gastric tuberculosis may include the ingestion of unpasteurized milk infected with bovine tuberculosis or a severely immunocompromised condition2). In cases of gastric tuberculosis such as this, nodal involvement is usually extensive, and the route of spread is thought to be the coeliac lymph nodes. Other possible mechanisms include direct mucosal invasion, hematogenous spread, extension from adjacent structures, and superinfection of a pre-existing ulcer or malignancy2, 8).

Abdominal pain is the symptom most commonly associated with gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Other symptoms, including diarrhea, fever, anorexia, weight loss, and constipation, are usually observed, but hematemesis, as seen in this case, is extremely rare1, 7, 11). It has also been suggested that, although intestinal tuberculosis results in increased capillary vascularity, small arteries undergo obliterative endarteritis in tuberculosis. This would explain the rarity of bleeding in such cases12).

The differential diagnosis of gastric tuberculosis includes adenocarcinoma, gastric lymphoma, benign peptic ulcer disease, Crohn's disease, syphilis, and sarcoidosis2). Endoscopy plays an important role in diagnosis. Single and multiple ulcers have been associated with this disease, as have hypertrophic nodular lesions surrounding a stenotic pyloric channel1). The associated ulcers are typically found to be irregular with a necrotic base, which may extend into perforation. Fistulae and anorectal lesions may also occur. These features are non-specific, and are also frequently observed in Crohn's disease7).

A definitive diagnosis essentially relies on a histological approach, normally involving Ziehl-Neelsen staining for acid-fast bacilli and culturing. Histopathological findings of caseating epithelioid cell granulomas are very helpful, but granulomas, whether caseous or noncaseous, are frequently found to be negative on endoscopic biopsies. Tuberculosis is strongly suggested when caseation is present. However, central acute necrosis of granulomas is also sometimes observed in Crohn's disease7). When granulomas are non-caseating, small, and discrete, the differential histological diagnosis includes Crohn's disease, sarcoidosis, syphilis, mycotic lesions, and exposure to beryllium, silicates, or reserpine8). Findings of acid-fast bacilli or positive cultures are also quite unusual in extrapulmonary lesions, and the absence of such findings is insufficient to exclude the diagnosis of tuberculosis3, 9). One of the reasons for this is the very low diagnostic yield of endoscopic biopsy specimens. For example, in a series of 50 patients with colonic tuberculosis sampled over a 10-year period, specific diagnostic features, such as the presence of caseation on histological study, positive staining for acid-fast bacilli, or a positive culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, were seen in a mere 18% of patients13). PCR testing of biopsy specimens may facilitate diagnosis and allow the exclusion of Crohn's disease with a 100% specificity and a sensitivity of 27 to 75%9). Another advantage to this method is that results can be obtained in 48 hours, rather than in the weeks that may be required for other methods7). Due to inaccurate clinical diagnoses, most patients end up requiring surgical intervention, only after which is gastric tuberculosis diagnosed7, 8). Regarding the present case, we were able to demonstrate neither AFB bacilli, nor caseating granulomas, but we did obtain a positive PCR test from the endoscopic biopsy. Fortunately, although endoscopically, the condition of the patient resembled a very aggressive gastric malignancy, we diagnosed gastric and colonic tuberculosis, thereby obviating the necessity of operation. The coexistence of carcinoma and tuberculosis may occur in 10% of gastric tuberculosis cases4). In this case, however, the clinical response to antituberculosis treatment and repeated endoscopic examination also confirmed our diagnosis8). In general, surgery is reserved for tuberculosis cases involving refractory or severe bleeding, or gastric obstruction2).

Although gastric tuberculosis is a rare condition, in patients presenting with endoscopic evidence of diffuse chronic inflammatory activity, the possibility of gastric tuberculosis should be considered, particularly in areas in which tuberculosis maintains endemicity8).

In conclusion, here we report a rare and interesting case of gastric tuberculosis which mimicked advanced malignancy, responded well to antituberculosis medication, and did not require surgery. Although gastric tuberculosis is usually located in the ileocecal region of the gastrointestinal tract,clinicians must bear in mind that tuberculosis can involve any site in the gastrointestinal tract, and may present with a variety of characteristics, even in the absence of an immunodeficient condition, as seen in this case. Gastric tuberculosis should always be part of the differential diagnosis of chronic infiltrative lesions in the stomach.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print