INTRODUCTION

Three types of monoclonal antibodies are widely used for therapy of lymphoma with the approval of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration1). These are unconjugated antibodies such as rituximab and alemtuzumab or a conjugated antibody with radioactive iodine, tositumomab. Rituximab was the first developed monoclonal antibody that targets CD20 and is currently the most extensively studied and clinically used. In combination with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone), the standard chemotherapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, rituximab has demonstrated a complete response (CR) rate of 61~76% in phase II and III trials2, 3). There have been no significant increase of adverse events in studies with a superior survival in a rituximab-CHOP arm compared to a CHOP only arm. A relatively low incidence of follicular lymphoma exists in Korea compared to Western countries. In this subtype of lymphoma, rituximab combined with CHOP or fludarabine has shown nearly a 100% response rate4, 5). Adverse events associated with rituximab therapy have been primarily infusion-related and include: fever, chills and skin eruption. Severe respiratory adverse events have been infrequent and reported in less than 0.03 percent of cases6). There have been five cases with interstitial pneumonitis related to rituximab therapy in combination with CHOP or as single therapy when used for lymphoma or immune thrombocytopenic purpura7-10). There are no known risk factors for this serious adverse event. Here, we report two patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in whom interstitial pneumonitis developed with rituximab therapy.

CASE REPORT

CASE 1

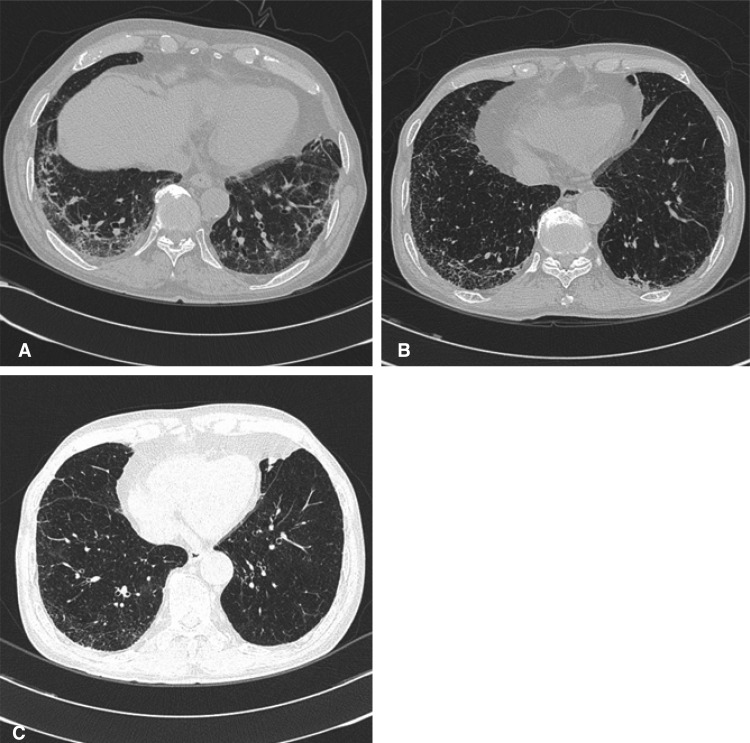

A previously healthy 73-year-old man visited our hospital because of a left cervical mass. Incisional biopsy of the cervical node revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma stage IIIA. The patient received seven cycles of R-CEOP combination chemotherapy (rituximab 375 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 750 mg/ m2, epirubicin 50 mg/m2 and vincristine 2 mg IV on D1 and prednisolone 100 mg PO on D1-5). The response was partial after the 6th cycle. After the 3rd cycle of R-CEOP, he complained of cough and purulent sputum. A chest computed tomography revealed sub segmental consolidation with peripheral ground glass opacity (GGO) in left upper lobe of the lung. After the administration of parenteral antibiotics, symptomatic improvement and disappearance of the infiltration on X-ray were observed. After an additional four cycles of chemotherapy, he complained of cough, sputum and exertional dyspnea, NYHA class II. Auscultation revealed end-expiratory Velcro-like rales at both lower lung fields. Arterial blood gas analysis was PH; 7.49, PaCO2; 29.2 mmHg, PaO2; 74.3 mmHg, and HCO3; 22.5 mmol/L. The cultures of blood and sputum were all negative for bacteria, tuberculosis and fungi. Chest computed tomography showed a markedly increase in the extent of sub pleural GGO at both lungs (Figure 1A). Pulmonary function testing showed a mild restrictive pattern with FEV1; 2.19 L/min (87% of normal predicted value), FVC; 2.60 L/min (68% of normal predicted value), FEV1/FVC; 84%, and DLCO; 10.3 mL/mmHg/min (59% of normal predicted value). A bronchoalveolar lavage sample showed a lympho-dominant nature with a CD4/CD8 ratio of 1.5. After the diagnosis of interstitial pneumonitis, methylprednisolone 60 mg qd was administered for five days. Symptomatic improvements were followed by a change of dose to prednisolone 20 mg once daily. After five weeks of steroid therapy, pulmonary function testing showed an objective response with FEV1; 1.90 L/min (71% of normal predicted value), FVC; 2.57 L/min (63% of normal predicted value), FEV1/FVC; 74%, and DLCO; 13.4 mL/mmHg/ min (74% normal predicted value).

CASE 2

This 66-year-old man visited our hospital because of a right testicular mass (8├Ś6 cm), which was detected one year prior to presentation and recently grew larger and became painful. After orchiectomy, the pathologic diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, stage IVA with unilateral involvement of bone marrow. He received five cycles of R-CEOP combination. His had a complete response after the 3rd cycle. After the 5th cycle of R-CEOP, he complained of cough and dyspnea, NYHA class II. Auscultation revealed end-expiratory Velcro-like rales at both lower lung fields. Chest computed tomography showed a markedly increased centrilobular and subpleural GGO and multiple consolidations in both lung fields (Figure 1B). Pulmonary function testing showed a mild obstructive pattern and decreased diffusing capacity with a FEV1; 1.95 L/min (76% of normal predicted value), FVC; 3.09 L/min (83% of normal predicted value), FEV1/FVC; 63%, and DLCO; 10.8 mL/mmHg/min (70% of normal predicted value). Bronchoalveolar lavage was refused by the patient. Symptomatic improvements were achieved two weeks after a prednisolone 10 mg qd daily regimen. After two months of steroid therapy, pulmonary function testing showed an objective response with a FEV1; 1.84 L/min (67% of normal predicted value), FVC; 3.33 L/min (83% of normal predicted value), FEV1/FVC; 56%, and DLCO; 15.5 mL/mmHg/min (89% of normal predicted value). Chest computed tomography demonstrated improvement (Figure 1C)

DISCUSSION

Monoclonal antibodies are targeting agents for tumor-specific antigens on tumor cells. As the first developed, and the most widely used monoclonal antibody, rituximab targets the CD20 antigen of B-cell lymphoma. The mechanisms by which rituximab acts include activation of cell-mediated cytotoxicity and complement-mediated cytotoxicity resulting in the release of several cytokines and apoptosis of tumor cells11). The expression of CD20 antigens is greater than 95% in B-cell lymphoma; for normal B-cells it is nearly zero in precursor B-cells and stem cells12). Therefore, mature B-cell lymphoma such as diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma all respond to rituximab, accompanied by the depletion of normal B-cell immunity. The apparent and frequent adverse events with rituximab are infusion-related fever, chills and flushing which occur frequently during or just after the first infusion. Other non-hematologic adverse events are nausea, vomiting, hypotension, angioedema, bronchospasm, and chest pain. These symptoms and signs are of mild to moderate severity in more than 95% of cases and spontaneously resolve after the cessation of the infusion. Rare hematologic toxicities include transient thrombocytopenia, leukopenia and hypogammaglobulinemia12).

Severe adverse events related to rutuximab have been reported in less than 5% of patients and severe lung abnormalities that interrupt further therapy are extremely rare. Five cases with interstitial pneumonitis induced by rituximab have been reported in Western countries and Japan. In Korea, there has been no prior report of interstitial pneumonitis with rituximab. The pathogenesis of interstitial pneumonitis resulting from rituximab may be related to the release of the inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-╬▒, IL-8, and IFN-╬│13). The risk factors for interstitial pneumonitis are generally: smoking, occupational exposure to dusts, advanced age, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypotension and obesity14). Our two patients had no risk factors except for advanced age, 73 and 66 years. The median age of the previously reported patients was 77. Therefore, cautious monitoring for respiratory symptoms during rituximab-containing therapy is mandatory in geriatric patients.

The diagnosis of interstitial pneumonitis is possible when typical symptoms and signs such as exertional dyspnea, dry cough, abnormal breathing sounds and a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing are combined with radiological abnormalities such as GGO and multiple infiltrations on computed tomography. If these findings are equivocal, a lung biopsy helps to confirm the diagnosis. Our two patients were exposed to neither drugs known to induce interstitial pneumonitis nor environmental risk factors. The mainstay of treatment for interstitial pneumonitis includes immunosuppressive agents such as steroids with a response rate reported as 20%15). The previously reported five patients were all treated with low- to high-dose steroids based on disease severity and further rituximab therapy was withheld. After the two to three weeks of steroid therapy, four patients showed objective improvement on pulmonary function testing. One patient showed resolution of the chest infiltrates on chest computed tomography. A patient who did not respond to steroid therapy underwent lung biopsy and subsequently died; the pathological findings from this patient were characterized by generalized thrombosis and suggested that the primary lung injury was a vascular event7-10). Our two patients also showed an objective response to low dose steroid treatment.

At present, rituximab is widely accepted as a targeting agent for B-cell lymphoma with high efficacy and low side effects. Additional concern for the severe adverse events in specific high risk groups such as geriatric patients is necessary.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print