|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 21(2); 2006 > Article |

|

Abstract

Primary pancreatic lymphoma is rare, comprising 0.2~4.9% of all pancreatic malignancies and less than 1% of cases of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Many patients are diagnosed with lymphoma after radical resection. We report a rare presentation of diffuse large B cell lymphoma, appearing as a primary tumor of the pancreas. A 61-year old female was admitted to the hospital with the complaint of right upper abdominal pain. Computed tomography of the abdomen showed a well defined mass located at the head of the pancreas. A frozen section of pancreas, during laparotomy, revealed lymphoma. The patient received 6 cycles of chemotherapy and is currently in complete remission. This case underscores the importance of differentiating primary lymphoma from the more common adenocarcinoma of the pancreas as treatment and prognosis differ significantly. Primary pancreatic lymphoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic tumors and an attempt to obtain a tissue diagnosis is always necessary before proceeding to radical surgery, especially on young patients.

Ductal adenocarcinoma accounts for 85% to 9% of pancreatic tumors1). Primary pancreatic lymphoma is rare, comprising 0.2~4.9% of all pancreatic malignancies and less than 1% of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL)2-4). Treatment and prognosis of these tumors are different. However, the diagnosis of primary pancreatic lymphoma is very difficult, because the clinical symptoms and signs resemble those of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Many patients are diagnosed as having lymphoma only after invasive radical resection. Here we report a rare presentation of diffuse large B cell lymphoma, appearing as a primary tumor of the pancreas.

A 61-year old female was admitted to the hospital with the complaint of right upper abdominal pain in February 2003. On admission, the patient had a temperature of 36.9℃, blood pressure of 115/58 mmHg, and a pulse of 68 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed a palpable non-tender mass in the right upper abdomen and icteric sclera. The hemoglobin was 8.2 g/dL with 6,400 leukocytes/mm3 and 247,000 platelets/mm3. The alanine aminotransferase was 129 U/L (normal range (NR), 5-40 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase was 65 U/L (NR, 5-33 U/L). The alkaline phosphatase was 615 U/L (NR, 35-129 U/L) and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase was 212 U/L (NR, 8-61 U/L). The total bilirubin was 16 mg/dL with 12 mg/dL of direct bilirubin. The serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) was 36.9 U/mL (NR, 0-37 U/mL). The abdominal ultrasound demonstrated a hypoechoic 3.4 cm sized mass located at the head of pancreas; there was dilatation of the bile duct and the gallbladder appeared to be filled with sludge. Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed a well defined mass located at the head of the pancreas which was slightly enhanced during the arterial phase (Figure 1). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) revealed stenosis of the distal common bile duct by extrinsic compression. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage was performed because of the clinical signs of fever and leukocytosis, suggesting acute cholangitis.

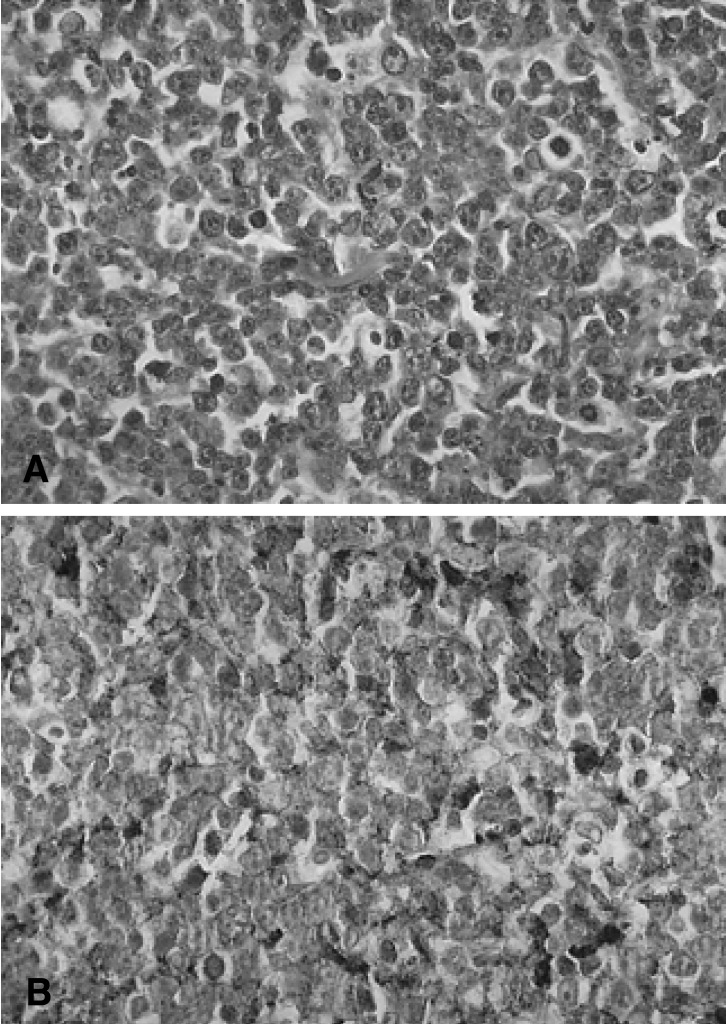

Laparotomy was performed, revealing a prominent mass located at the head of the pancreas accumulated with the duodenum and the portal area. A frozen section of pancreas revealed lymphoma and partial excision of the mass located at the pancreatic head was performed instead of the Whipple procedure. Microscopic examination revealed a malignant lymphoma which consisted of large anaplastic lymphocytes (Figure 2A). The round or oval nuclei showed condensation of chromatin patterns with nucleoli. The cytoplasm was scanty or eosinophilic. Mitotic figures were easily identified. Tumor cells showed strong membrane staining for the B cell marker protein (CD20) and were negative for the T cell marker protein (CD3) (Figure 2B). Therefore, according to the Ann Arbor classification, the patient had stage IE disease.

Six cycles of CHOP chemotherapy (cyclophophamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) were administered without any further complications. Follow-up abdominal CT showed no visible mass in the pancreas (Figure 3). The patient is currently in complete remission and in good general condition.

NHL frequently occurs at extranodal sites, most commonly in the gastrointestinal tract and rarely in the pancreas5). In this case the criteria for the definition for primary pancreatic lymphoma as used by Behrns and associates, were satisfied7). These criteria include: no superficial or mediastinal adenopathy, normal leukocyte count, and findings confined to peripancreatic disease (Ann Arbor stage I or II) without hepatic or splenic involvement6, 7).

Clinical manifestations of pancreatic lymphoma include abdominal pain (75%), a palpable abdominal mass (54%), weight loss (50%), jaundice (40%), night sweats (22%) and fever (20%)3, 6). These symptoms are similar to those associated with ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. Laboratory findings provide no additional information to differentiate pancreatic masses. Double-contrast enhanced spiral CT is the imaging modality of choice and demonstrates the presence of a pancreatic mass in virtually all patients6). Lymphoma should be suspected in the presence of a large, rapidly growing pancreatic mass4, 8). It is unlikely to have a pancreatic adenocarcinoma above 10 cm in size; about 60% of pancreatic lymphomas are greater than 6 cm in diameter3). The presence of lymphadenopathy in the peri-pancreatic area, splenomegaly and as well as a large tumor, generally without encasement of the superior mesenteric artery, are suggestive of lymphoma. The location of the tumor in the pancreas does not appear to be helpful in determining whether the mass is carcinoma or lymphoma. In the absence of any pathognomonic clinical or radiological features, the diagnosis is established only on histopathological examination. The use of a CT guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) has the advantage of not requiring an open surgical procedure but has the disadvantages of sampling error, difficulty in evaluating obtained sample (false positive/false negative) and the inability to subclassify the lymphoma3, 5). In a review of 269 percutaneous biopsies of pancreatic lesions with CT or ultrasound guidance, the combined accuracy in the diagnosis of malignancy was 93%, major complications were seen in three cases and no biopsy related death occurred9, 11). Recently, endoscopic ultrasonography with FNA has also been used successfully to identify and biopsy pancreatic lymphoma6, 10). Open biopsy of the pancreas provides more tissue and allows direct visualization of the lesion and other abdominal organs and lymph nodes, but carries the morbidity and mortality associated with a surgical procedure3). With the availability of less invasive diagnostic modalities, operating to obtain tissue for pathologic diagnosis should be reserved for the rare instance when all other available modalities have failed to provide a final tissue diagnosis6).

The management of primary pancreatic lymphoma is controversial. Behrns et al. advised a more aggressive surgical approach including pancreatic resection or tumor debulking, in view of the poor survival rate with radiotherapy and chemotherapy7). Currently, many institutions with a large experience of operative management for pancreatic disease have reported mortality rates of 5% or less after major pancreatic resection with an acceptable morbidity rate of 30%6, 8). However Webb et al. reported that no evidence supported a role for extensive resection in the management of patents with pancreatic lymphoma, and that the majority of patients should be managed with chemotherapy and without surgery4, 8). Extensive surgery frequently causes a variety of complications which may prevent patients from receiving chemotherapy. Radiation remains a suggested general adjuvant to chemotherapy to increase the local control regardless of anatomic location6). Bouvet and colleagues reported the use of radiation therapy in all cases of lymphoma of the pancreas not treated with surgery; they reported four of eight patients with long term survival after standard chemotherapy and radiotherapy5). Local failure either from residual or recurrent disease has been noted by multiple authors and accounts for more than 85% of deaths (28 of 32). Because of these frequent local failures, additional therapies directed to local control should be considered6). Therefore, it is very important to establish a definitive diagnosis and stage of disease, to plan the modality of treatment. The range of survival time is wide and few conclusions are available since the data is not directly comparable3). The primary treatment for patients in whom the diagnosis of lymphoma can be established, with minimally invasive techniques, is combination chemotherapy with involved-field radiotherapy5). Surgical resection may play a beneficial role in the treatment of localized pancreatic lymphoma6).

Lymphoma is an uncommon cause of obstructive jaundice, and the management for this diagnosis is controversial. Operative decompression of the bile ducts, with biliary-enteric bypass, has been recommended as it allows for rapid resolution of jaundice before initiation of chemotherapy. Others have observed equally rapid resolution of jaundice with a short course of radiotherapy or nonhepatotoxic chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide and prednisone). Endoscopic stenting when feasible is another viable option11).

NHL is curable in more than 50% of patients with anthracycline containing combination chemotherapy regimens and radiotherapy. The treatment of pancreatic lymphomas with chemotherapy and radiation shows mixed results. Webb et al. reported complete remission in six of nine patients treated with chemotherapy at a median follow-up of 24 months. In another report, a 40% relapse-free survival was reported in 14 patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation6, 8, 11). Adnan et al. reported that all five patients studied achieved a complete remission, and only one relapsed at 12 months after treatment; while the others remain in remission at 84, 26, 24 and 21 months11).

It is important to differentiate between primary lymphoma and the more common adenocarcinoma of the pancreas as treatment and prognosis differ significantly. Primary pancreatic lymphoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic tumors and an attempt to obtain tissue diagnosis is always necessary before proceeding to radical surgery, especially on young patients.

References

1. Cubilla AL, Fitzgerald PJ. Atlas of tumor pathology. 1984;2nd ed. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 109–183.

2. Kalil AN, Reck dos Santos PA, Azambuja DB, Beck PE. A case of retroperitoneal lymphoma presenting as pancreatic tumor. Hepatogastroenterology 2004;51:259–261PMID : 15011880.

3. Salvatore JR, Cooper B, Shah I, Kummet T. Primary pancreatic lymphoma: a case report, literature review, and proposal for nomenclature. Med Oncol 2000;17:237–247PMID : 10962538.

4. Webb TH, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Jones RJ, Cameron JL. Pancreatic lymphoma: is surgery mandatory for diagnosis or treatment? Ann Surg 1989;209:25–30PMID : 2910212.

5. Bouvet M, Staerkel GA, Spitz FR, Curley SA, Charnsangavej C, Hagemeister FB, Janjan NA, Pisters PW, Evans DB. Primary pancreatic lymphoma. Surgery 1998;123:382–390PMID : 9551063.

6. Koniaris LG, Lillemoe KD, Yeo CJ, Abrams RA, Colemann J, Nakeeb A, Pitt H, Cameron JL. Is there a role for surgical resection in the treatment of early-stage pancreatic lymphoma? J Am Coll Surg 2000;190:319–330PMID : 10703858.

7. Behrns KE, Sarr MG, Strickler JG. Pancreatic lymphoma: is it a surgical disease? Pancreas 1994;9:662–667PMID : 7809023.

8. Ueda K, Nagayama Y, Narita K, Kusano M, Mernyei M, Kamiya M. Pancreatic involvement by non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2000;7:610–613PMID : 11180896.

9. Brandt KR, Charboneau JW, Stephens DH, Welch TJ, Goellner JR. CT- and US-guided biopsy of the pancreas. Radiology 1993;187:99–104PMID : 8451443.

Figure 1

Computed tomography showing well defined mass with slight enhancement during the arterial phase.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print