|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 26(1); 2011 > Article |

|

Abstract

Somatostatinomas are rare functioning carcinoid tumors that usually arise in the pancreas and duodenum. They are seldom associated with typical clinical symptoms; their diagnosis is confirmed only by histological and immunohistochemical studies and the presence of specific hormones. Two distinct clinicopathological forms of somatostatinoma exist: duodenal and pancreatic somatostatinomas. Clinically, compared to pancreatic somatostatinomas, duodenal somatostatinomas are more often associated with nonspecific symptoms and neurofibromatosis, but less often with somatostatinoma syndrome or metastasis. Histologically, duodenal somatostatinomas frequently have psammoma bodies in the tumor cells. We report a case of duodenal somatostatinoma in 58-year-old man with vague epigastric pain and nausea. He did not have diabetes, steatorrhea, or cholelithiasis. Abdominal computed tomography showed a 25-mm mass in the duodenum and 25-mm nodule in the liver. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showed a duodenal submucosal tumor. Although the endoscopic biopsies were free of malignancy, the patient subsequently underwent Whipple's operation for the duodenal mass. Examination revealed as a somatostatinoma using a special stain for somatostatin.

Carcinoid tumors, relatively rare neuroendocrine neoplasms arising from enterochromaffin cells, were first described by Lubarsch in 1888 [1]. Since 1974, functional neuroendocrine tumors have been classified according to the major hormones secreted, such as insulinoma, gastrinoma, VIPoma, glucagonoma, and somatostatinoma. Since the first two case reports of somatostatin-secreting tumors in 1977, fewer than 200 cases of somatostatinoma have been reported [2]. The pancreas is the most common site of somatostatinoma (68%), followed by the duodenum (19%), ampulla of Vater (3%), and small intestine (3%) [3]. Typical somatostatinomas are large, solitary, malignant tumors that are often discovered with lymph node or liver metastases at the time of diagnosis [4]. The clinical presentation includes abdominal pain, nausea, obstructive jaundice, and endocrinopathy, such as a somatostatin syndrome. Krejs et al. [5] first reported somatostatin syndrome in 1979. It is caused by excess somatostatin released from the somatostatinoma and consists of the clinical triad of diabetes mellitus, cholelithiasis, and steatorrhea [5].

Here, we report a case of a nonfunctional duodenal somatostatinoma and review gastrointestinal somatostatinomas.

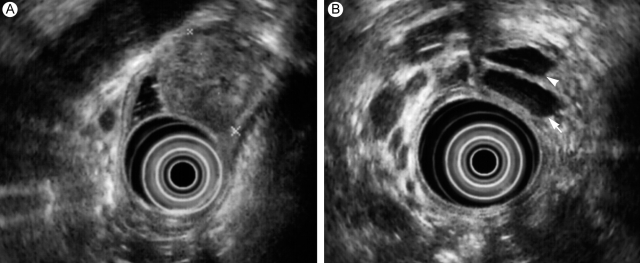

A 58-year-old man was referred to our hospital for evaluation of a periampullary mass detected on ultrasonography. He had suffered from vague epigastric pain and nausea for about 1 month. Abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) revealed a 25-mm mass in the medial side wall of the second portion of the duodenum at the level of the ampulla of Vater (Fig. 1A) and a 25-mm ill-defined lowattenuating nodule in the left medial segment of liver (S4) (Fig. 1B). The intrahepatic duct, common bile duct (CBD), and pancreatic duct (PD) were dilated. The total serum bilirubin was 0.5 mg/dL, and the serum AST/ALT was 38/47 IU/L. Other laboratory findings were normal. The tumor markers CA19-9, carcinoembryonic antigen, and a-FP were all in the normal ranges. His fasting blood sugar was 118 mg/dL, but a glucose tolerance test was normal. Neither neurofibromatosis nor multiple endocrine neoplasms were detected. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed an enlarged ampulla of Vater covered with a smooth mucosal surface (Fig. 2). However, the orifice was too narrow to insert the scope for a cholangiopancreatogram. Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed a well demarcated mass under the duodenal mucosa that compressed the distal lumens of the CBD and PD, and caused dilatation of the proximal CBD and PD (Fig. 3). Biopsies from ERCP showed only chronic nonspecific duodenitis with lymphocyte infiltration.

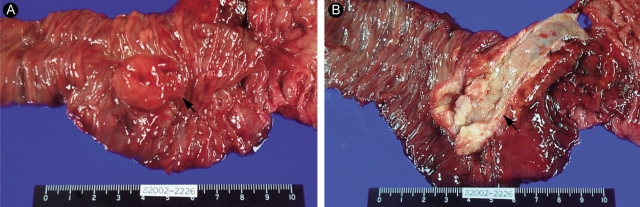

Ten days later, the patient underwent Whipple's operation (pancreaticoduodenectomy), since the tumor was highly suspicious for malignancy at endoscopy. At surgery, a 2.5 × 2.5-cm enlarged ampulla of Vater was found at the second portion of the duodenum; its surface was smooth and covered with duodenal mucosa. The regional and periaortic lymph nodes were enlarged. A hepaticojejunostomy was also performed, and all of the enlarged lymph nodes were dissected.

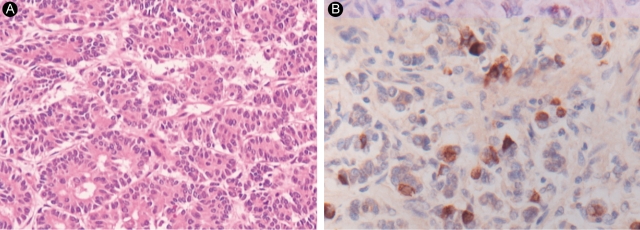

The pathological examination showed a 2.3 × 2.3 × 2-cm mass located mainly in the duodenal submucosa, abutting the superficial muscle layer of the duodenum (Fig. 4). The ampulla of Vater was elevated, but free of malignancy. The tumor was located in the duodenal submucosa and distal CBD, dilating the CBD. All resected tumor margins and dissected lymph nodes were free of tumors. A microscopic examination revealed that the tumor consisted of uniform cells arranged in solid nests, cords, and glandular patterns without psammoma bodies (Fig. 5A). The tumor cells stained for chromogranin A, synaptophysin, and somatostatin (Fig. 5B). They were argyrophilic on Churukian Schenk's staining, but non-argentaffinic on Fontana-Masson staining. We diagnosed it as a primary duodenal somatostatinoma.

One month later, he was discharged without complications. At the 6-month follow-up, abdominopelvic CT showed no recurrent mass and the previous hepatic nodule.

A somatostatinoma, a carcinoid tumor arising from enterochromaffin cells, is a relatively rare neuroendocrine tumor; the pancreas is the most common site of somatostatinomas. Somatostatin is a cyclic tetradecapeptide widely distributed in normal human tissues and secreted by the hypothalamus, cerebrum, spinal cord, vagus nerve, and D cells in Langerhans islets of the pancreas, stomach, duodenum, and small intestine [6]. Somatostatin inhibits numerous endocrine and exocrine secretory hormones, including insulin, cholecystokinin, pancreatic enzymes, and gastrin [4,6]. Nonspecific symptoms such as vague abdominal pain, nausea, weight loss, and altered bowel habits are more common than somatostatin syndrome [4]. Somatostatin syndrome occurs only with pancreatic somatostatinomas or extrapancreatic tumors larger than 4 cm [4]. Duodenal somatostatinomas are detected relatively earlier and are generally smaller than pancreatic somatostatinomas. They frequently present with abdominal pain, obstructive jaundice, cholelithiasis, vomiting, and abdominal bleeding, rather than typical somatostatin syndrome [7].

In this case, the tumor originated from the duodenum and was smaller than 4 cm. The patient had only vague nonspecific symptoms. Unfortunately, the serum insulin, glucagon, gastrin, somatostatin, and urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels were not checked. Before the exploratory laparotomy, the tumor was thought to be an adenocarcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. The serum somatostatin level is usually elevated in functioning tumors, although duodenal somatostatinomas are usually non-secretory. Given the nonspecific symptoms and laboratory findings, microscopic and immunohistochemical studies typically enable a specific diagnosis.

The histological features of somatostatinomas are similar to those of other carcinoid tumors. The tumor cells are arranged uniformly in trabecular, acinar, ribbon, or cribriform structures. They have few mitoses with little necrosis and are separated by stroma [8]. The most distinct histological characteristic of somatostatinomas is the psammoma body. These spherical bodies have been reported in somatostatinomas of the ampulla of Vater, and in pancreatic and extrapancreatic somatostatinomas, papillary thyroid cancers, serous ovarian tumors, and meningiomas [9]. Psammoma bodies were reported in 68% of duodenal somatostatinomas [7].

Most carcinoid tumors stain positively for chromogranin A, neuron-specific enolase, Leu-7, and specific endocrine cell markers. On classical silver staining, 75% to 80% of carcinoid tumors are argyrophilic, while they are seldom argentaffinic [8]. Since the pathological findings of our tumor concurred with somatostatinoma, we diagnosed it as a duodenal somatostatinoma.

Considering its malignant potential, surgical resection is the recommended treatment for this tumor. Generally, for tumors 1 cm or smaller, endoscopic excision is adequate because of the low incidence of metastasis. For lesions between 1 and 2 cm, transduodenal excision should be applied. Larger lesions are more aggressive and invasive. Tumors larger than 1 cm are likely to invade to deep layer beyond the submucosa [10] and endoscopic resection cannot always remove the tumor completely. The malignant nature of duodenal somatostatinomas and the risk of metastasis increase significantly in tumors larger than 2 cm. For larger tumors (> 2 cm), Whipple's operation with a regional lymphadenectomy should be considered, even if all of the regional lymph nodes are negative in preoperative imaging studies [10]. Regardless of the size of the primary tumor, if abnormal lymph nodes are detected, the tumor and all of the regional lymph nodes should be removed [10]. This recommendation is based on the experience with duodenal gastrinomas, for which surgical resection of lymph node appears to improve survival [10]. With liver metastases of neuroendocrine tumors, cytoreductive therapy, such as segmentectomy or lobectomy, is effective. Therefore, somatostatinomas with hepatic metastases are suitable candidates for hepatic resection.

Since supporting data are lacking, adjuvant chemotherapy for somatostatinomas is not recommended. Palliative chemotherapy for unresectable or advanced tumors has only limited value. Multi-agent regimens, such as combinations of streptozocin, fluorouracil, cyclophosphamide, or doxorubicin, produce limited responses in patients with metastatic disease. Octreotide is useful for reducing the symptoms of somatostatin syndrome in inoperable patients. The overall 5-year survival for patients with somatostatinoma is 40% to 60% [4]. The 5-year survival rate is 40% in somatostatinomas with liver metastasis, but 100% in tumors without liver or lymph node metastases.

References

1. Lubarsch O. Uber den pimaeren krebs des ileum nebst Bemerkungen ueber das gleichzeitige Vorkommen von krebs und tuberculos. Virchows Arch 1888;111:280–317.

2. Larsson LI, Hirsch MA, Holst JJ, et al. Pancreatic somatostatinoma: clinical features and physiological implications. Lancet 1977;1:666–668PMID : 66472.

3. Kimura R, Hayashi Y, Takeuchi T, et al. Large duodenal somatostatinoma in the third portion associated with severe glucose intolerance. Intern Med 2004;43:704–707PMID : 15468970.

4. House MG, Yeo CJ, Schulick RD. Periampullary pancreatic somatostatinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2002;9:869–874PMID : 12417508.

5. Krejs GJ, Orci L, Conlon JM, et al. Somatostatinoma syndrome. Biochemical, morphologic and clinical features. N Engl J Med 1979;301:285–292PMID : 377080.

6. Mahajan SK, Mahajan LA, Malangoni MA, Jain S. Somatostatinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc 1996;44:612–614PMID : 8934174.

7. Tanaka S, Yamasaki S, Matsushita H, et al. Duodenal somatostatinoma: a case report and review of 31 cases with special reference to the relationship between tumor size and metastasis. Pathol Int 2000;50:146–152PMID : 10792774.

8. Hoffmann KM, Furukawa M, Jensen RT. Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors: classification, functional syndromes, diagnosis and medical treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2005;19:675–697PMID : 16253893.

9. Kelley T. Somatostatinoma. Probl Gen Surg 1994;11:99–119.

Figure 1

Abdominal computed tomography shows a well-defined mass at the duodenal second portion (A) and a low-attenuating nodule in the left medial segment of liver (S4) (B).

Figure 3

The endoscopic ultrasonography view reveals a 2.6-cm submucosal mass (A), along with common bile duct (arrow) and pancreatic duct (arrowhead) dilatation (B).

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Topical Steroids to Treat Granulomatous Mastitis: A Case Report2011 September;26(3)

Gastric Yolk Sac Tumor: A Case Report and Review of the Literature2009 June;24(2)

Duodenal Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma: A Case Report2007 December;22(4)

Agenesis of the Dorsal Pancreas: A Case Report and Review of the Literature2006 December;21(4)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print