A Study of the Bronchial Provocation Test with Methacholine in Patients with Active Pulmonary Tuberculosis

Article information

Abstract

Bronchial hyperreactivity is a characteristic feature of bronchial asthma. Recent respiratory infections, allergic rhinitis, atopic family history, pulmonary tuberculosis, pulmonary sarcoidosis, cystic fibrosis, and farmer’s lung have also been demonstrated to have bronchial hyperreactivity to inhaled methacholine. It is not known if pulmonary tuberculosis can cause nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity and what the mechanism would be. We therefore undertook to evaluate nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity in active pulmonary tuberculosis using the bronchial provocation test with methacholine and we measured the total serum IgE and peripheral eosinophil count to seek some mechanisms.

There were 5 patients among 18 subjects with active pulmonary tuberculosis whose response to methacholine was positive. The mean baeline FEV1 of positive responders was 71.40 ± 17.39%, and that of negative responders was 110.18 ± 17.65%(p<0.05). There were no significant differences in serum IgE and peripheral eosinophil count between positive and negative responders.

We found that active pulmonary tuberculosis would increase the nonspecific bronchial response with methacholine, and the mechanism of the bronchial hyperreactivity in patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis may not be related to an immunologic mechanism but may be related to the stimulating receptors.

INTRODUCTION

Bronchial hyperreactivity is a characteristic feature of bronchial asthma and there are allergen-specific and nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivities. Allergen-specific bronchial hyperreactivity is only observed in extrinsic asthma, but nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity is increased by several factors, including exposure to offending allergens. This is often found in chronic obstructive lung disease and can be caused transiently by viral upper respiratory infections and vaccination of influenza virus6–8). There were some reports that bronchial hyperreactivity can be a manifestation of bronchiectasis8), pulmonary sarcoidosis10), cystic fibrosis11) and pulmonary tuberculosis9).

Several mechanisms have been reported to explain nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity, but none of them has been clearly identified. It is not determined whether pulmonary tuberculosis can cause nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity and what the mechanism is. Bronchial provocation tests with methacholine, histamine, or the physical stimuli of exercise are useful in the assessment of nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity5).

The aim of the present study was to examine nonspecific bronchial hyperreactivity in active pulmonary tuberculosis, using bronchial provocation tests with methacholine, which is a parasympathomietic drug that produces bronchial smooth muscle contraction, and we measured total serum IgE and peripheral eosinophil count to evaluate some mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

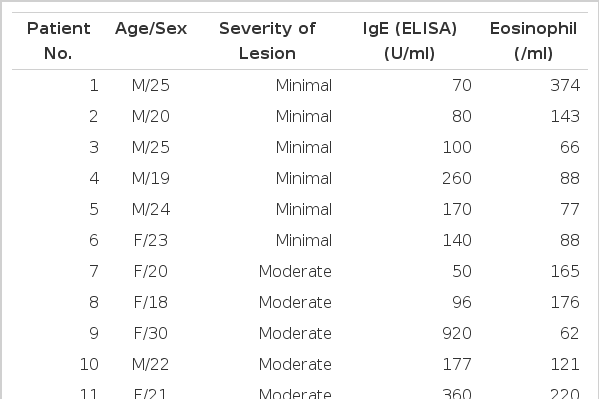

Eighteen patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis participated in this study. This group consisted of 12 men and 6 women, 18 to 54 years of age (mean age 27.5 years) with basal FEV1 over 60% predicted (pred) value and FVC over 80% pred value.

The selected subjects were proven to have active tuberculosis with sputum AFB, bronchoscopic washing AFB, or bronchoscopic biopsy. The patients with a history of previous respiratory allergy or pulmonary tuberculosis medication were excluded.

The potential subjects underwent a physical examination and pulmonary function test, including complete spirometry, before and after inhalation of methacholine.

The severity of the pulmonary tuberculosis lesion was determined by chest X-ray and we checked the serum IgE level and serum total eosinophil count with the ELISA technique.

We used the methacholine chloride with the following structural formula:

In our laboratory, a 20% or greater reduction in FEV1 constituted a positive response to methacholine.

After inhalation of normal saline as a basal study, serial administration of the methacholine aerosol with a nebulizer was begun with an FEV1 maneuver performed after each dose (0.31, 0.62, 1.25, 2.5, 5.0, 10.0, and 25.0 mg/ml). Three and a half minutes following inhalation of five deep breaths of the diluent, the pulmonary function studies were repeated.

The test was terminated when the FEV1 had decreased 20% or more from the patient’s baseline or in the absence of a positive response when the dosage schedule was complete.

If the test was negative, five breaths of the next dilution was given at 5 minute intervals. Finally, a bronchodilator aerosol (e.g. salbutamol inhalator) was administered to reverse the bronchoconstrictive effects of methacholine if the test appeared positive.

RESULTS

1. Baseline Spirometry

According to the lesions of pulmonary tuberculosis, 3 groups were defined: subjects with minimal pulmonary tuberculosis (n = 6) showed a mean FEV1 of 118% pred (64–140% pred) and mean FVC of 103.7% pred (86–120% pred); subjects with moderate pulmonary tuberculosis (n = 7) showed a mean FEV1 of 97.6% pred (64–140% pred), and a mean FVC of 92% pred (65–126% pred); and subjects with far advanced pulmonary tuberculosis (n = 5) had a mean FEV1 of 79.2% pred (64.117% pred) and a mean FVC of 82.2% pred (49–91% pred).

The mean baseline FEV1 of positive responders was significantly lower than that of negative responders to the bronchial provocation test with methacholine (Table 3, Fig. 1), (positive responders, 71.40 ± 17.39%; negative responders, 110.18 ± 17.65%, p<0.05).

Also, the mean baseline FVC of positive responders was significantly lower than that of negative responders to the bronchial provocation test with methacholine (Table 3, Fig. 2), (positive responders, 77.80 ± 14.99%; negative responders, 99.08 ± 17.42%, p<0.05).

2. Airway Responses to Methacholine

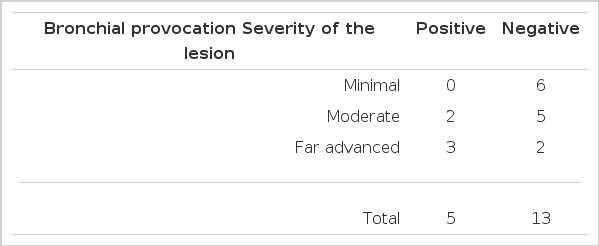

Five patients showed positive responses to the methacholine bronchial provocation test among 18 patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis. All patients with minimal pulmonary tuberculosis showed negative responses to the bronchial provocation test with methacholine.

But 2 patients among 7 subjects with moderate pulmonary tuberculosis and 3 patients among 5 subjects with far advanced pulmonary tuberculosis revealed positive responses to the methacholine bronchial provocation test (Table 2).

3. Serum IgE Levels

Mean total IgE values were 529.90 U/ml (SD = 524.26) in positive responders and 297.25 U/ml (SD = 264.16) in the negative ones.

But there were no significant differences in the serum total IgE levesl between the 2 groups (t = 0.9835, p>0.1), (Table 3, Fig. 3).

4. Serum Eosinophil

Mean blood eosinophil count was 260.60/ml (SD = 104.72) in the positive responders and 164.64/ml (SD = 125.36) in the negative ones.

Although eosinophil count in the positive responders was higher than in the negative responders, there was no significant statistical difference between the 2 groups (t = 1.4847, p>0.1), (Table 3, Fig. 4)

DISCUSSION

The bronchial inhalation challenges with pharmacologic and antigenic substances were introduced to North American for the detection of airway hypersensitivity and hyperreactivity in the 1940’s1–4). The successful application of inhalation challenge techniques has improved our understanding of pathophysiologic and immunologic mechanisms of reactive airway disease5).

Although most subjects with current asthma are exquisitively sensitive to methacholine, bronchial reactivity can be demonstrated in the individuals without asthma.

Recent respiratory infections6), allergic rhinitis2), an atopic family history7), chronic pulmonary disease8), pulmonary tuberculosis9), pulmonary sarcoidosis’10), cystic fibrosis, and farmer’s lung12) have all been demonstrated to influence the bronchial response to inhaled methacholine.

When patients with hyperreactive and hypersensitive airways are exposed to aerosolized pharmacologic bronchoconstriction substances or antigens to which they have become senitized, they will usually develop one of 3 responses, i.e. immediate response, late reponse, and combined response’13).

Possible causes for the exaggerated smooth muscle contraction in bronchial hyperreactivity include a decrease in baseline airway caliber, an increased responsiveness of the smooth muscle itslef, an abnormality in the autonomic stimulus to the target cells”14). The age also has a significant effect on the methacholine responsiveness, that is, younger and older subjects may exhibit a bronchial response that may falsely suggest hyperreactive airway disease18). But the age group of 20 to 60 years does not demonstrate a significant age effect18,19). The age group in this study was 18 to 54 years, so there was no significant age affect.

Three pharmacologic agents are currently used for bronchial inhalation challenges and they are methacholine, carbachol, and histamine. Methacholine is a parasympathomimetic drug that produces bronchial smooth muscle contraction when delivered in sufficient dose by aerosol. Methacholine is slowly broken down in the body by cholinesterase, while carbachol is not significantly inactivated by the enzyme. Inhaled parasympathomimetic drugs produce their effect on the airways by stimulating acetylcholine receptors in bronchial smooth muscle cells15–18,21,22).

The most common parameter of spirometry appears to be the one second forced expired volume (FEV1) for clinical bronchial reactivity testing. In this study we used the FEV1 as a parameter for bronchial hyperreactivity evaluation.

In summary, the resonse to methacholine was positive in five patients among 18 subjects with active pulmonary tuberculosis (2 patients among 7 subjects with moderate pulmonary tuberculosis and 3 patients among 5 subjects with far advanced pulmonary tuberculosis). The mean baseline FEV1 of positive responders was significantly lower than that of negative responders to the bronchial provocation test. There were no significant differences in serum IgE and eosinophil count between positive and negative responders.

In this study, we found that active pulmonary tuberculosis would increase the non-specific bronchial response with methacholine, and the responses were prominent in the subjects with lower FEV1. Because there were no significant differences in the serum IgE and blood eosinophil count between the 2 groups, we suggest that the mechanism of bronchial hyperreactivity in subjects with active pulmonary tuberculosis may not be an immunologic mechanism but may be related to the stimulating receptors.

However, a bronchial provocation test with extracts of tubercle bacilli or long term follow-up studies for the attended subjects are necessary to elicit the more exact mechanism of bronchial hyperreactivity in patients with activie pulmonary tuberculosis.