Ovarian Granulosa Cell Tumor presenting as Meigs' Syndrome with elevated CA125

Article information

Abstract

Herein, a rare case of ovarian granulosa cell tumor, presenting as Meigs' syndrome, with elevated carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), is reported. A 69-year-old woman was admitted for the investigation of abdominal fullness and dyspnea. A preoperative examination revealed a huge pelvic tumor and an abdominopelvic magnetic resonance image (MRI) assumed ovarian cancer. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan revealed pleural effusion. A laparotomy confirmed the huge mass to be an ovarian tumor. A total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) and partial omentectomy, was performed. Although short-term intrathoracic drainage was required, the hydrothorax and ascites rapidly resolved in the postoperative period.

INTRODUCTION

The constellation of findings consisted of a solid ovarian mass, ascites and hydrothorax, which should be considered as a malignant process until proven otherwise. However, in 1937, Meigs and Cass1) reported the clinical picture of nonmalignant ascites and/or pleural effusion in association with a benign ovarian tumor, with resolution of the ascites and hydrothorax after removal of the ovarian lesion, which thereafter has been called Meigs' syndrome2, 3). When the same clinical features exist, but involve other ovarian or gynecologic tumors, it is referred to as pseudo-Meigs' syndrome4, 5). Ovarian sex cord stromal tumors represent approximately 5% of all ovarian cancers. Granulosa-stromal cell tumors, including granulosa cell tumors, thecomas and fibromas, are the most common diseases of sex cord stromal tumors, and may be associated with endometrial hyperplasia and an endometrial carcinoma6). Granulosa cell tumors are low-grade, estrogen secreting malignancies, and can be seen in women of all ages. An ovarian mass and an elevated serum CA125 level in a postmenopausal woman generally suggest a malignant process.

Herein, a case of Meigs' syndrome from an ovarian granulosa cell tumor, with elevated CA125, and the unique principles of its management are reported, with a review of the literature.

CASE REPORT

A 69-year-old Korean woman was admitted to our hospital complaining of abdominal fullness and dyspnea. Her family and medical histories were unremarkable. On physical examination, there was dullness to percussion, with decreased breath sounds in the lower half of the right lung field, a huge palpable mass in the lower abdomen, and on a rectovaginal examination a large, smooth solid mass was palpated on the left adnexa.

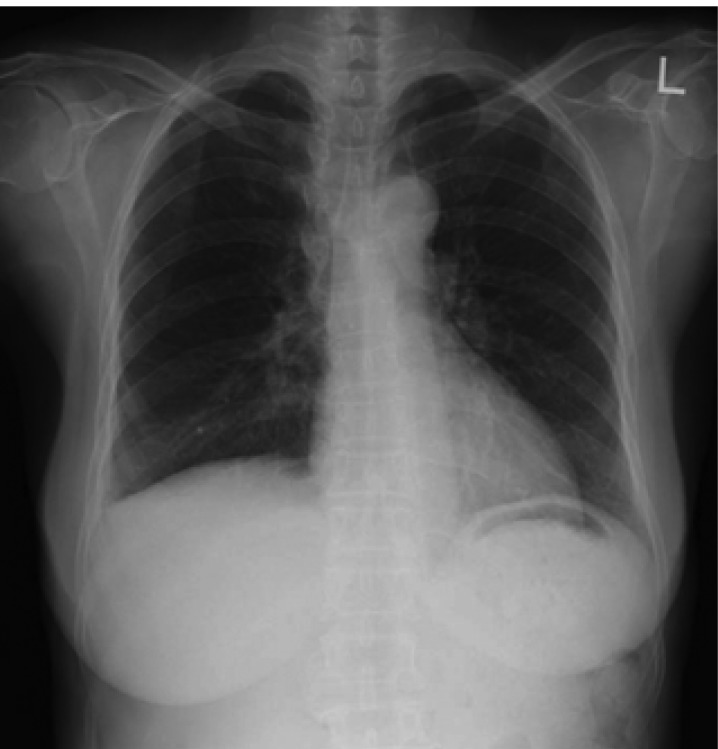

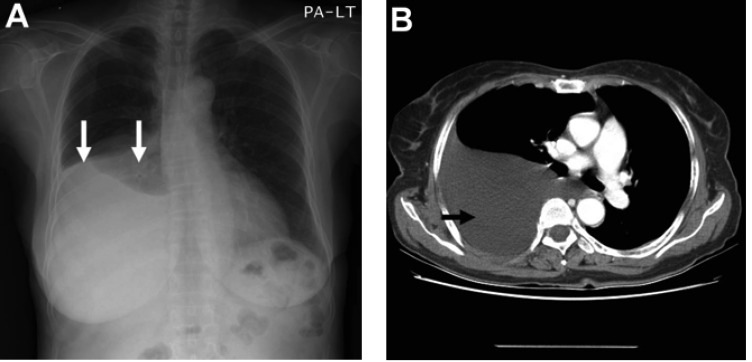

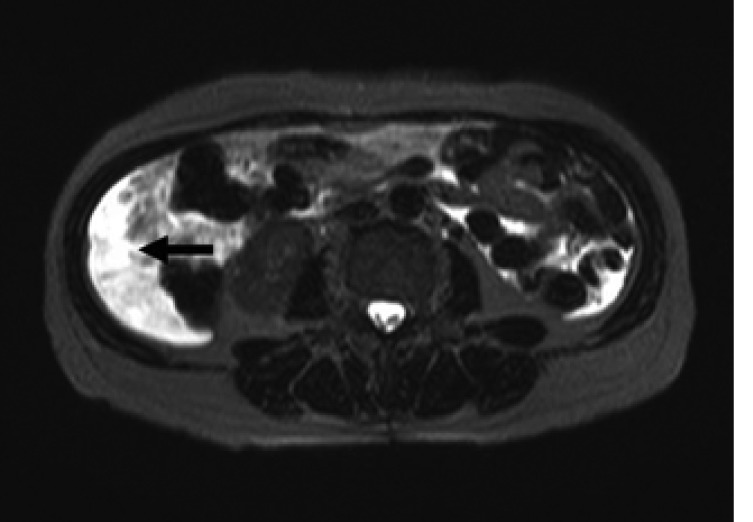

Laboratory data on admission were within normal limits. A chest X-ray (Figure 1A) and CT scan (Figure 1B) showed massive right pleural effusion, and ultrasonography, CT and MRI scans revealed a 6×10×12 cm in sized intrapelvic huge solid mass, including cystic components involving both adnexae and the uterus, and a moderate amount of intra-abdominal fluid collection (Figure 2, 3). The MRI and CT scans showed no evidence of a metastatic disease involving the lymph nodes, bone or abdominal organs. The serum CA125 concentration was 82.49 U/mL (normal, 0~35 U/mL). The serum levels of carcinoembrionic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) were normal. A cytological examination of both the ascites and pleural fluid showed no signs of malignant cells. An explorative laparotomy was performed based on the suspicion of ovarian cancer. Serous ascites, a moderately enlarged uterus and a large right ovarian mass were found, but there were no signs of metastatic spread. A total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) was performed, with a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO), partial omentectomy and pelvic lymph nodes sampling. During the operation, the ovarian tumor ruptured in the pelvic cavity and 2,500 mL of serous ascites were drained during the laparotomy. Due to the right pleural effusion, a trocar tube was inserted into the right thorax, with a total of 650 ml of serous fluid collected.

(A) Chest X-ray film showing right pleural effusion (arrows). (B) Contrast enhanced CT scan showing large amount of pleural effusion (arrow)

Magnetic resonance imaging on the T2-weighted images showing an intra-abdominal fluid collection (arrow).

Magnetic resonance imaging on the T2-weighted images showing about 6×10×12 cm size, a well defined solid mass including cystic components in pelvic cavity (arrows), compressing rectosigmoid colon.

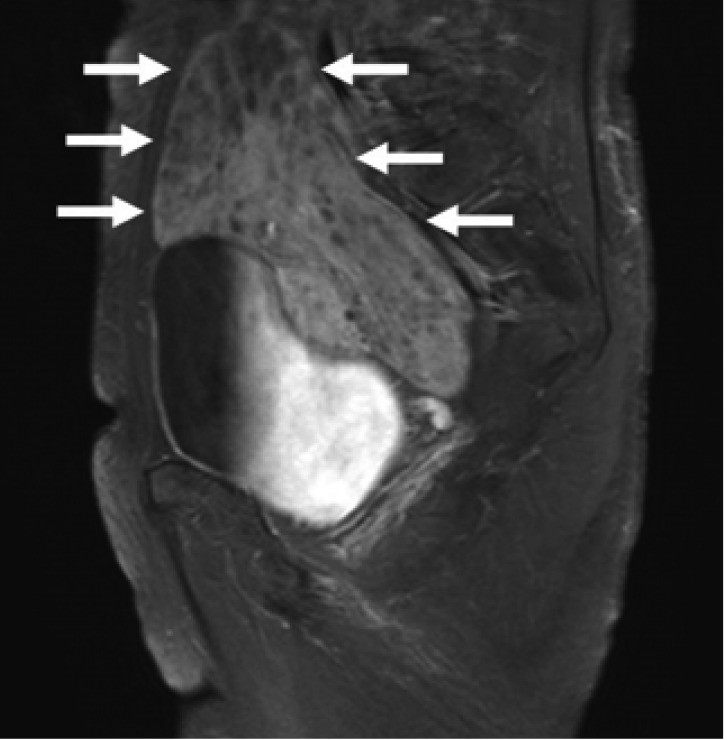

The specimens of the left ovary and salpinx, macroscopically, showed a previously ruptured fragile, with numerous grayish brown ovary tissues. Necrosis or hemorrhage was not found. Microscopically, this neoplasm was composed of diffuse sheets of round to oval cells. The nuclei of this tumor were pale and round and oval or angular and have occasional nuclear grooves (Figure 4). The totally removed uterus measured 7×4×2.2 cm in size, and showed adenomyosis and senile endometrium. The right ovary and salpinx were grossly clean, but no definitive lesion was found. The resected partial omentum showed no malignant findings. Resected left and right pelvic lymph nodes were no tumor in 13 lymph nodes. A cytological examination of the ascites drained during the operation showed no sign of malignant cells. The final diagnosis of the left ovarian mass was that of a granulosa cell tumor. The pathologic stage of the tumor was designated as T1cNOMO and IC, according to the TNM stage and to the International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) staging system, respectively.

The mass is composed of diffuse sheets of round to oval cells and the nuclei of this tumor are pale, round and oval or angular and have occasional nuclear grooves (H&E stain, ×400).

The hydrothorax and ascites rapidly resolved in the early postoperative period (Figure 5), and the trocar tube was removed on the seventh postoperative day. Four cycles of postoperative chemotherapy were planned due to the tumor rupturing during the operation. The adjuvant chemotherapy consisted of CAP (cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2, adriamycin 50 mg/m2 and cisplatin 50 mg/m2 on day 1) regimen. Each cycle was repeated every 28 days. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course. The serum CA125 level declined, and had normalized 2 months after surgery.

DISCUSSION

Meigs and Cass1) described a rare triad of benign, solid ovarian tumor, with the gross appearance of a fibroma (e.g., an actual fibroma, a thecoma, or a granulosa cell tumor), ascites and hydrothorax, where a cure was achieved by completely removing the benign tumor. This has now come known as Meigs' syndrome2-4). This syndrome occurs in association with only 1 to 2 percent of fibromas, which in themselves are rare in children2). Since the original description by Meigs, ascites and hydrothorax have been reported in a variety of other gynecologic conditions, including fibroids7), degenerative ovarian changes, mature cystic teratoma and ovarian-hyperstimulation syndrome, and are usually referred to as "pseudo-Meigs' syndrome". However, as Ryan5) indicated, the discrimination of true Meigs' syndrome is considered fundamentally academic, and does not affect the therapeutic aspects of the problem8).

The mechanism of formation of the ascites is unknown, but several theories have been offered to explain the origin of the hydrothorax and ascites in Meigs' and pseudo-Meigs' syndrome. Meigs believed it due to leakage from the fibroma, as fibromas are frequently edematous, possibly due to pressure on the lymphatic vessels on the tumor's surface2). It has also been suggested that the presence of fluid results from cyst formation within the tumor as a result of injury or necrosis. Meigs showed the hydrothorax generally developed from movement of the ascitic fluid into the pleural space through congenital defects in the diaphragm. Generally, a plausible theory explaining Meigs syndrome has been proposed, as follows; first, the ascites may be caused by transudation of interstitial edema fluid from the tumor. In relation to this explanation, Samanth and Black9) proposed a discrepancy between the arterial supply to a large mass of tumor tissue, and that it's venous and lymphatic drainage could lead to stromal edema and transudation. Second, it is possible that pressure on the lymphatics in the tumor itself may cause the escape of fluid through the superficial lymphatics situated just beneath the single layered cuboidal epithelium covering the tumor10). Third, the production of fluid by the peritoneum, other than around the tumor surface, has recently been suggested as the main factor in the production of ascites8).

Recently, Abramov et al.11) reported that the findings strongly suggested the involvement of vasoactive growth factor (VEGF and FGF) and the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 in the pathogenesis of Meigs' syndrome. All 3 factors possess potent vascular permeability-enhancing properties, and have been associated with capillary leakage and the formation of ascites and pleural effusion in other gynecologic abnormalities, such as the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome12) and ovarian cancer. Concentrations of all 3 vasoactive factors were significantly higher in the ascites than in the serum. This suggests local rather than systemic secretion of these factors by the ovarian neoplasm mediates the hyperpermeability of the ovarian or peritoneal vasculature, with the subsequent transudation of fluid into the peritoneal cavity. The etiology of hydrothorax is also unclear, although the transfer of ascitic fluid via the transdiaphragmatic lymphatic channels is the current prevailing theory13, 14). This would explain the disappearance of ascites after the excision of the tumor. Both the ascites and pleural effusion in our case disappeared 2 months after surgery.

CA125 is a cell-surface antigen associated with a high molecular weight glycoprotein. Although the highest levels of CA125 are seen in association with a pelvic malignancy, such as ovarian cancer with dissemination, there is no CA125 value 100% specific for ovarian cancer. Elevated levels have been noted in various benign processes, such as endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, pregnancy, ascites and benign ovarian tumors9, 15, 16). In our case, the elevated serum CA125 level was strongly suggestive of primary ovarian cancer, with the decline and normalization of the elevated levels after surgery confirming the association of raised CA125 levels with ovarian granulosa-cell tumors. Due to the rarity of this disease, Meigs' syndrome caused by an ovarian granulosa cell tumor may be misdiagnosed as severe peritoneal and pleural dissemination.

Granulosa cell tumors are the most common sex cord-stromal tumors, and may be associated with endometrial hyperplasia and an endometrial carcinoma. In general, they tend to present with a stage I disease and are frequently associated with hormonal effects, such as precocious puberty, amenorrhea, postmenopausal bleeding or virilizing symptoms. However, in our case, no entometrial lesion or hormonal effects were found.

The surgical staging of sex cord-stromal tumors is the same as that for epithelial ovarian cancers, with their surgical management based on the tumor stage and age of the patient17). In women who have completed childbearing, the surgery should be more aggressive, including a TAH, with a BSO and the standard surgical staging. Women older than age 40 at diagnosis are more likely to experience a recurrence of granulosa cell tumors, which is why adjuvant therapy is recommended older populations, although definitive evidence for its efficacy in preventing or delaying recurrences is lacking. Patients with an advanced stage disease (i.e., stage II to IV) may benefit from additional therapy, with cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy being the most frequently used treatment18, 19).

The overall 5 and 10 year survivals were 87 and 76%, respectively. Eighty percent of granulosa cell tumors were diagnosed as stage I, according to FIGO staging system. The 10 year survival rate after a recurrence was 56.8%, and the mitotic rate, tumor stage and residual tumor disease were associated with a poor prognosis20). In our case, with an age of 69-years and an IC stage, cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy was performed due to the rupturing of the ovarian tumors in pelvic cavity during the operation.

In conclusion, an intrapelvic tumor, with ascites, pleural effusion and elevated serum CA125, should suggest a malignant ovarian tumor, but if both the ascites and pleural effusion cytology are negative, the diagnosis and treatment of Meigs' syndrome is required. Clinicians should be aware that an ovarian granulosa cell tumor may cause Meigs' syndrome, and that resection of the ovarian lesions can improve the prognosis.