Acute Respiratory Failure Associated with Cryptococcal Pneumonia and Disseminated Cryptococcosis in an AIDS Patient

Article information

Abstract

A 36-year-old homosexual Mexican man was admitted to our hospital, with a 30-day history of fever and headache. Upon cerebrospinal fluid examination, the patient's white blood cell count was 1,580/L, total protein was 26 mg/dL, sugar was 17 mg/dL, and his intracranial pressure was 23 cmH2O. The patient was diagnosed with HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) infection by serum Western blotting. Cryptococcus neoformans was isolated in cultures of the patient's blood and cerebrospinal fluids. Chest computerized tomography revealed diffuse reticulonodular infiltration and a ground-glass appearance in both perihilar regions, suggestive of either Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia or cryptococcal pneumonia. On the patient's 6th day in our hospital, bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial lung biopsy were conducted via bronchoscopy, and a pathologic examination of lung biopsy specimens revealed signs of cryptococcal pneumonia.

This patient died on his 14th day in our hospital, as the result of acute respiratory failure, associated with cryptococcal pneumonia and disseminated cryptococcosis.

INTRODUCTION

The respiratory tract is the site most commonly infected with opportunistic organisms in AIDS patients, and respiratory failure is the leading cause of death in these cases. In the 1980s, the vast majority of cases of respiratory failure were determined to have been the result of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). However, AIDS patients now commonly receive antibiotic prophylaxis against PCP, and thus acute respiratory failure is attributed to PCP in only two-thirds of current cases. However, the incidence of acute respiratory failure induced by infection with other organisms is being increasingly encountered1).

Initial clinical symptoms and radiographic evidence of cryptococcal pneumonia in AIDS patients may be initially similar to those of PCP, but the mortality associated with cryptococcal pneumonia is much higher than that associated with PCP. Therefore, the rapid diagnosis of cryptococcal pneumonia, particularly in immunocompromised hosts, including AIDS and cancer patients, is crucial2, 3).

Here, we present a case of disseminated cryptococcal infection, including acute respiratory distress syndrome associated with cryptococcal pneumonia, cryptococcemia, and cryptococcal meningitis, in an AIDS patient.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old man was admitted to our hospital, with a 30-day history of fever and headache. The patient, a homosexual Mexican, had entered Korea 4 months prior to admission. One year prior to admission, the patient had experienced a mild fever, diarrhea, and 20 kg of weight loss. On admission, this patient's body temperature was 38.5℃, and his blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg. He was alert, and was found to have oral thrush. The patient's breath sounds were clear, and his heart sounds were regular, with no murmur. Hepatomegaly and splenomegaly were noted. Upon neurological examination, neck stiffness and Kernig signs were noted. Upon a cerebrospinal fluid examination, the patient's white blood cell count was 1,580/L, total protein was 26 mg/dL, sugar was 17 mg/dL, and intracranial pressure was 23 cmH2O.

The patient was diagnosed with HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) infection via serum Western blotting assay. The total number of CD4+ T lymphocytes and CD8+ T lymphocytes were 7 and 60/L. The patient also had an HIV RNA level of 41,000 copies/mL. Cryptococcus neoformans was isolated on cultures of blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

On the day of admission, an initial chest roentgenogram revealed no specific abnormal findings, and the patient was treated with intravenous amphotericin B and ceftriaxone as empirical therapy for possible bacterial and fungal infection.

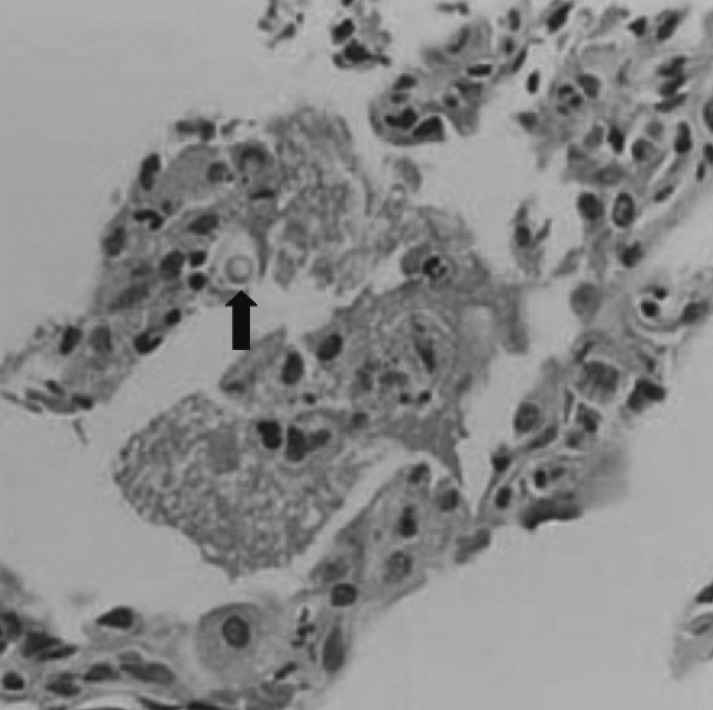

On the patient's 4th day in our hospital, a chest roentgenogram revealed diffuse interstitial infiltrations in both lung field, and computerized tomography revealed diffuse reticulonodular infiltration and a ground-glass appearance in both perihilar areas, suggesting PCP or cryptococcal pneumonia (Figure 1).

Diffuse reticulonodular infiltrates with ground glass opacities in the whole lung field on a computed tomography scan.

On the patient's 6th day in our hospital, bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial lung biopsy were conducted via bronchoscopy, and antiretroviral therapy (didanosine, lamivudine, nelfinavir) was initiated. Results of methenamine silver staining of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid revealed no specific abnormal findings. After the patient's 6th day in our hospital, the patient's breathing difficulties and arterial hypoxemia worsened.

On the patient's 9th day in the hospital, his arterial oxygen pressure and saturation level were measured at 32.7 mmHg and 61.6%, and mechanical ventilation was initiated.

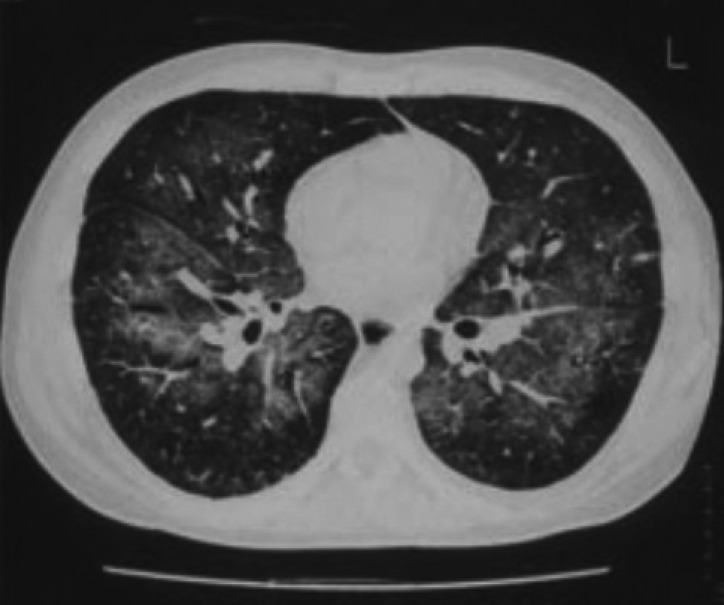

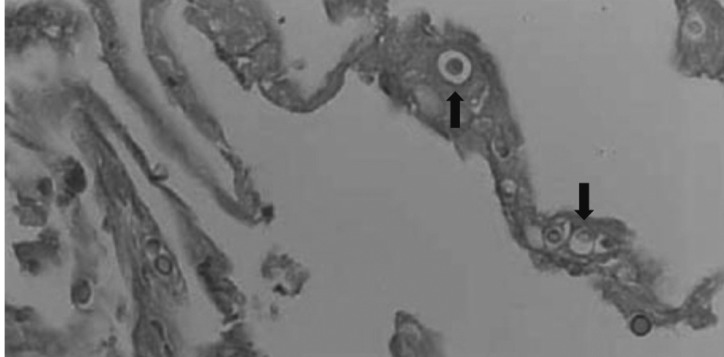

Cultures of the patient's blood and CSF samples, obtained at the time of admission, revealed Cryptococcus neoformans. Pathological findings and the special stain results of lung biopsy specimens, obtained at the time of bronchoscopy, also revealed cryptococcal pneumonia (Figures 2, 3).

PAS positive yeasts, morphologically consistent with Cryptococcus neoformans in lung parenchyma. Lung Biopsy (PAS, ×400).

This patient died on his 14th day in our hospital, as the result of acute respiratory failure, associated with cryptococcal pneumonia and disseminated cryptococcosis.

DISCUSSION

Acute respiratory failure with cryptococcal pneumonia in AIDS patients is associated with disseminated disease and a high level of mortality. However, the diagnosis of cryptococcal pneumonia in its early periods is rather difficult, as the initial clinical symptoms and radiographic signs of cryptococcal pneumonia in AIDS patients are practically indistinguishable from those of Pneumocystis carinii (P. carinii) pneumonia, which is the most commonly encountered cause of acute respiratory failure in AIDS patients2-4).

Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans) is the fourth most commonly recognized life-threatening infection-causing organism in AIDS patients, after cytomegalovirus (CMV), P. carinii, and Mycobacterium avium intracellulare (MAI)5). P. carinii, CMV, and MAI are known to induce diffuse interstitial pneumonias in AIDS patients. C. neoformans is also known to induce diffuse interstitial pneumonia in AIDS patients.

The initial clinical manifestations of cryptococcal pneumonia in AIDS patients are similar to those seen in cases of P. carinii pneumonia, but the mortality associated with cryptococcal pneumonia is much higher. Cryptococcal pneumonia-induced acute respiratory failure is associated with a mortality rate of nearly 100%, and most of those patients progress to disseminated cryptococcosis. Due to the rapidity with which cryptococcal pneumonia progresses to acute respiratory failure in AIDS patients, it is fairly difficult to diagnose cryptococcal pneumonia in its early stages. It is also quite difficult to distinguish cryptococcal pneumonia from P. carinii pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia, and miliary tuberculosis, as cryptococcal pneumonia is characterized by a variety of radiological findings, including interstitial infiltrations, alveolar consolidation, a ground-glass appearance, miliary nodules, lymphadenopathy, and pleural effusion6, 7).

When an AIDS patient contracts pneumonia and the results of an induced sputum examination are negative, the accepted course of action is to administer an early check-up, including a bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage, in order to detect a possible mycotic infection which may prove fatal8).

The possibility of mycotic infections, such as cryptococcal pneumonia, must also be investigated in cases in which steroid therapy is administered for the treatment of P. carinii pneumonia9, 10).

The above case represents an example of disseminated cryptococcosis which, in its early stages, manifested the classic symptoms of encephalomeningitis, in a patient in whom Cryptococcus neoformans was cultured in cerebrospinal fluid and blood cultures. Our patient died as the result of galloping pneumonia with acute respiratory insufficiency, although he was being treated with a course of intravenous amphotericin B. This patient exhibited disseminated cyptococcosis, but the diagnosis presented difficulties, as the radiological findings revealed perihilar density and a ground-glass appearance, both of which are also classic characteristics of P. carinii pneumonia. In this patient, P. carinii could not be identified on a bronchoalveolar lavage examination. However, cryptococcal pneumonia was diagnosed in the patient's lung biopsy samples.

An AIDS patient suffering from Cryptococcus neoformans, like this one in this study, often exhibits the same early clinical patterns and radiological findings observed in patients suffering from P. carinii pneumonia. However, early diagnosis and treatment are crucial, particularly due to the much higher fatality rate associated with Cryptococcus neoformans1-3, 11).