Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Complicated by Left Ventricular Apical Necrosis and Aneurysm in a Young Man: FDG-PET Findings

Article information

Abstract

A 29-year old male was transferred to our hospital with an abnormal chest X-ray finding diagnosed as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with apical necrosis and aneurysm formation. Four years after the initial hospitalization, we confirmed the aneurysm and necrosis using both integrated positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT) scanning. The F-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) PET/CT enabled precise localization of the aneurysm, which was found to be composed of semi-lunar calcification of non-metabolic myocardium. A contrast-enhanced CT angiography showed an hour-glass appearance of the left ventricular cavity. The integrated PET/CT fusion scanner is a novel multimodality technology that allows for a comprehensive analysis of the anatomical and functional status of complex heart disease. Based on these findings, long standing mechanical and physiologic abnormalities may have led to chronic ischemia in the hypertrophied myocardium, induced necrosis and calcification at the cardiac apex.

INTRODUCTION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is characterized by inappropriate myocardial hypertrophy which can occur in the absence of identified causes; it is the most common form of primary myocardial disease in Asian countries. Apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (AHCMP) is a variant that predominantly involves the cardiac apex and is much more common in Asian populations. We previously reported a case of AHCMP in a young man who presented with an atypical appearance of the left ventricular contour secondary to apical necrosis based on the findings of echocardiography, coronary angiography and myocardial perfusion scans. Four years after the initial work up, the precise anatomy as well as functional status were confirmed by F-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and contrast-enhanced CT angiography. Here we report these findings with images.

CASE REPORT

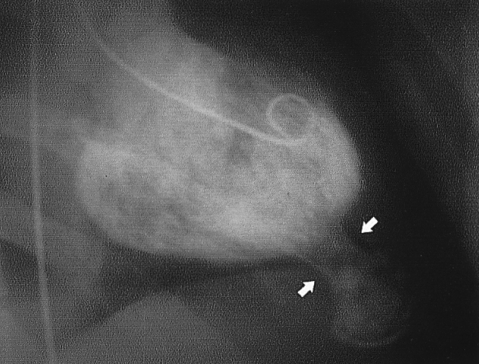

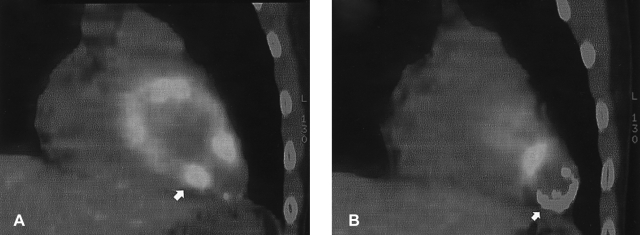

A 29-year-old male man without any medical history of heart disease was admitted with an abnormal chest X-ray finding on a routine medical examination. The patient did not have any symptoms such as dyspnea or palpitation. The chest X-ray and fluoroscopy showed a round shaped calcified density under the left diaphragmatic shadow (Figure 1). A left ventriculogram showed an hour-glass appearance of the left ventricular (LV) cavity. The apical sac was co-localized with the round calcification seen on the chest X-ray and fluoroscopy (Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with AHCMP complicated by apical necrosis and aneurysm formation. The signal-averaged ECG and 24-hour ECG monitoring did not reveal any abnormal findings. We recommended anticoagulation therapy to prevent systemic thromboembolism. Four years after the initial presentation, we performed a study with an integrated PET/CT scanner. Images were first acquired with a Discovery PET/CT scanner (GE Healthcare), and then integrated with an Advance NXi PET scanner with a LightSpeed Plus 8-row helical CT scanner. F-18 FDG was injected 45 min after oral glucose loading (50 g). Data acquisition was started 45 min after F-18 FDG injection and continued for 20 min. The data was iteratively reconstructed (ordered-subset expectation maximization) into attenuated cardiac PET images. On the mid-ventricular sagittal slices, a focal hypertrophic myocardial mass was seen at the apex of the left ventricle (Figure 3A). On a more lateral section, a crescent-shaped calcification with surrounding non-metabolic myocardium was seen at the location of the aneurysm (Figure 3B).

A left ventriculogram revealed a bottle gourd-shaped left ventricular contour with a passive filling at the apical aneurysm which connected with narrow long neck (arrows).

Two serial sections of sagittal cardiac F-18 PET/CT fusion images. A focal hypertrophic myocardial mass (arrow) is seen at the left apical ventricle (A). On a more lateral section, a crescent-shaped calcification (arrow) with hypometabolism was seen (B).

This integrated PET/CT scan was followed, without moving the patient, by contrast-enhanced CT angiography with 150 mL of contrast medium (4 mL/s) and simultaneous acquisition of 8 parallel slices. Images were acquired during a breath-hold after inspiration, and electrocardiography was recorded continuously. The F-18 FDG PET/CT images and three-dimensional reconstructions of the multi-slice spiral CT scans were performed using the Advantage Windows software package (version 4.1; GE Healthcare) that provides a coronary artery tree and the heart shape. Three-dimensional cardiac reconstruction showed a bottle gourd-shaped left ventricle with a calcified aneurysm, which was connected to the left ventricular apex with a long neck (Figure 4). On the basis of previous studies, we concluded that the long term mechanical and physiologic abnormalities might have induced myocardial necrosis and aneurysm formation. PET/CT images coupled with CT angiography combine images of structure and function, so providing more information when interpreting complex cardiac disease.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of multi-slice spiral CT angiography showing the shape of the heart. The apical aneurysm with calcification was connected to the apex of left ventricle with a long neck (A and B). The left anterior coronary artery was located more medially than usual at the left ventricular apex.

DISCUSSION

Echocardiography is still a useful technology for evaluating anatomical features of myocardial disease. The continuing improvements in both hardware and software, and the combination of images from multiple imaging modalities has resulted in a growing number of diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Fused PET/CT images and CT angiography provide non-invasive, high resolution morphology for evaluating cardiac and vascular disease. Since the introduction of the PET/CT fusion image system in 1998, we have been able to acquire more meaningful two and three-dimensional cardiac gated images. More recently, the 64-slice CT, a state-of-the-art scanner, has been developed to offer exceptional image quality; we used an 8-slice CT scanner in this study. Although echocardiography is still useful for evaluating anatomical features of CMP, there are limitations in its ability to evaluate the metabolic status and 3-dimensional structure of the myocardium in cardiac disease with complex anatomy. Here we report an unusual case of AHCMP with its metabolic and functional status assessed by use of PET/CT fusion images.

In 2004, we reported a case of AHPCM case in a young man. The diagnosis was based on echocardiography, left ventriculogram and single photon emission tomography (SPECT). SPECT images revealed the complete absence of 99mTc uptake at rest at the apical aneurysm. We could not match this with the calcification seen on the chest X-ray nor could we analyze the viability of the myocardium. Four years later, we re-evaluated this patient using a PET/CT fusion study and finally confirmed that the apical aneurysm was metabolically inert and may have occurred after long standing ischemic injury. Previously, several studies revealed reduced blood flow and metabolic abnormalities at the apex of hypertrophied myocardium. Reversible thallium defects, in the absence of coronary artery disease, occur frequently in patients with AHCMP despite the fact that the relationship between the presence of ischemia and adverse patient outcome is not unknown. In our case, coronary angiography did not reveal a stenotic lesion at the left anterior descending coronary artery, although its distal segment was deviated to the septum because of the aneurysm. Furthermore, apical hypertrophy leads to chronic cavity obliteration (CO) in the apical portion of the left ventricle and CO is an important pathophysiological condition as well as hypertrophy, ischemia, and prolonged QTc. These mechanical and physiologic abnormalities are jointly related to the development of aneurysm and necrosis through their interactions.

CT angiography is also emerging as a useful tool for understanding the 3-dimensional anatomical structure of complex disease. In our case, we could not obtain information about the aneurysm from echocardiography because of calcification and location. CT angiography provided excellent 3-dimensional images and was helpful for understanding the general morphology and relationships with neighboring structures.

In summary, fused PET/CT scanning and CT angiography are useful tools for evaluating functional and anatomical features of complex cardiac abnormalities. Long standing mechanical and metabolic abnormalities at the hypertrophied myocardium at the apex may lead to necrosis and aneurysm formation.