Delayed Rupture of the Right Sinus of Valsalva into the Right Atrium after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Article information

Abstract

Rupture of the sinus of Valsalva is an extremely rare complication after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Because it usually results from the retrograde extension of a dissection of the right coronary artery and may quickly spread to involve the entire aorta, it can cause life-threatening complications such as aortic dissection. If the dissection remains localized, it can resolve spontaneously in the first month. Our patient experienced a delayed rupture of the right sinus of Valsalva into the right atrium at approximately 3 months after PCI.

INTRODUCTION

Dissection of sinus of Valsalva is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), due to fatal outcomes such as aortic dissection. If the dissection remains localized, it will usually resolve spontaneously within one month, without expansion or rupture. Our patient experienced a delayed rupture of the right sinus of Valsalva into the right atrium at approximately 3 months after PCI.

CASE REPORT

In September 2006, a 69-year-old man visited the outpatient department complaining of exertional chest pain for the preceding 3 months. His risk factors included old age and a history of smoking. His resting electrocardiogram showed no specific abnormalities except for left axis deviation. Treadmill test was undertaken using the Bruce protocol. The result was positive at stage 3 (10.2 METs was attained), and horizontal ST depressions were observed in leads II, III, aVF, and V4-6 (maximal ST depression, 0.18 mV in amplitude). A 2-D echocardiogram revealed left atrial enlargement and left ventricular hypertrophy. Diagnostic coronary angiogram (CAG) demonstrated critical tubular stenosis in the proximal segment of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) and near total occlusion in the mid-segment of the left circumflex artery, with TIMI 2 flow and critical diffuse stenosis in the proximal to mid-segment of the right coronary artery (RCA) (Fig. 1A and 1B). We decided to first re-perfuse the RCA, engaged with a 6 Fr Judkins Right 4 guiding catheter to the RCA ostium. We were unsuccessful in our attempt to pass the 2.0 by 20 mm balloon, so we predilated with a 1.5 by 15 mm balloon with 8 atm pressure. After this ballooning, a RCA ostial dissection developed, which extended to the aorta (Fig. 1C). We stopped the procedure immediately and closely observed the patient in the coronary care unit. Six days later, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms were performed, with no abnormalities found (Fig. 2). Follow up CAG was performed, and dissection was still seen in the proximal segment of the RCA, without significant changes. We engaged the RCA with a 6 Fr Amplatz Left 1 guiding catheter. Two Cypher® Select stents (2.5 by 33 mm, 3.5 by 18 mm; Cordis, Miami, FL, USA) were implanted in the RCA (Fig. 1D), and a 3.0 by 24 mm Endeavor™ stent (Medtronics, Minneapolis, ML, USA) was implanted in the LAD. The patient recovered without complication and received follow-up care in the outpatient department after being discharged.

Diagnostic coronary angiogram. (A) Critical stenosis in the proximal segment of the left anterior descending artery and near total occlusion in the mid-segment of the left circumflex artery with TIMI 2 flow are noted. (B) Diffuse critical stenosis is noted in the proximal to mid-segment of the right coronary artery. (C) After ballooning, ostial dissection of the right coronary artery developed and extended to the aorta. (D) After 6 days, two Cypher Select stents (2.5 by 33 mm, 3.5 by 18 mm) were implanted in the right coronary artery.

Transesophageal echocardiography performed 6 days after percutaneous coronary intervention. No abnormal findings are shown, (A) long axis direction and (B) short axis direction.

Ao, aorta; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; AV, aortic valve.

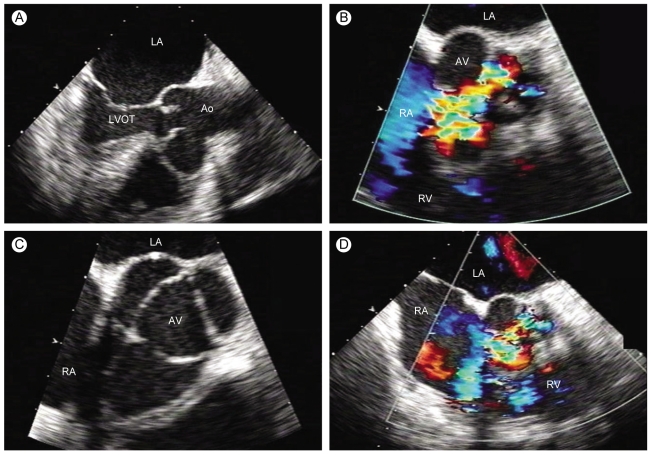

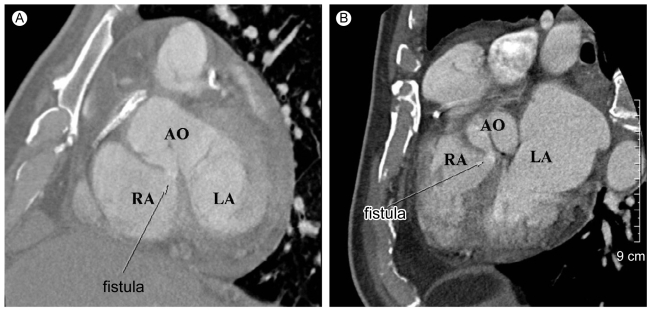

Three months after discharge, the patient complained of recurrent episodes of progressive exertional dyspnea (New York Heart Association class III). On physical examination, his blood pressure was 120/60 mmHg, with a heart rate of 90 beats per minute and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute. Auscultation revealed a grade 4/6 continuous cardiac murmur in the left parasternal area. The murmur was prominent in the diastolic phase. Transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography demonstrated bulging and rupture of the sinus of Valsalva with jet flow from the non-coronary cusp to the right atrium (RA) in the diastolic phase (Fig. 3), severe aortic regurgitation, and moderate mitral regurgitation. A restrictive pattern of mitral inflow with E/E' ratio of 17 was also noted. Coronary multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) showed that the right side of the sinus of Valsalva bulged into the side of the non-coronary cusp, with fistula flow from the non-coronary cusp to the right atrium (Fig. 4).

Transesophageal echocardiography performed 3 months later. Bulging with rupture of the sinus of Valsalva with jet flow in diastole from the non-coronary cusp to the right atrium is noted along with severe aortic regurgitation, (A) long axis direction, (B) long axis direction with color doppler, (C) short axis direction, and (D) short axis direction with color doppler.

Ao, aorta; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; AV, aortic valve.

Computed tomography scan. Bulging of the aortic root and fistula with jet flow in diastole from the noncoronary cusp to the right atrium is noted, (A) horizontal section and (B) vertical section.

RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; AO, aorta.

After identification of the rupture, surgical correction was performed under general anesthesia. Surgical findings included a sac-like cavity in the posterior portion of the right coronary sinus, intracardiac shunt from the right coronary cusp to the RA and left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT), intracardiac shunt from the LVOT to the RA, and tethering of the mitral valve with annular dilatation. The ruptured sinus was repaired with a Dacron patch closure of the intracardiac shunt from the right coronary cusp to the RA on the RA side, Teflon patch closure of the right coronary cusp side, bovine pericardium repair of the sinus, and aortic and mitral valvuloplasty. Postoperative echocardiography demonstrated trivial aortic regurgitation, trivial mitral regurgitation, and no remnant shunt.

DISCUSSION

Interventional cardiology is currently undergoing rapid development and refinement. In spite of the advancement, percutaneous treatment of more complex coronary lesions is still associated with a not insignificant level of morbidity. The incidence of procedure-related complications is the same as it was in the 1980s [1].

Dissection of the sinus of Valsalva after PCI usually results from the retrograde propagation of a proximal coronary dissection towards the aortic wall [2]. Rarely, localized dissection of the sinus of Valsalva without coronary arterial dissection is reported [3]. Although the precise mechanism is unclear, the etiology of coronary dissection during PCI has been proposed to be the result of the use of rigid wires, forceful manipulations of guiding catheters and balloon catheters, and vigorous contrast medium injection [1,2,4,5]. The shearing force of blood flow during systole and diastole could also explain the anterograde and retrograde propagation of the dissection [6]. This is similar to the mechanism that causes aortic dissection in a hypertensive patient. The entry ports created by mechanical trauma and/or forceful injection of contrast medium into the subintimal space are already exposed to the aortic blood stream, which, contributes to the subsequent extension of the dissection [7]. Some investigators have suggested that degenerative medial diseases, such as cystic medial necrosis and atherosclerotic change, might also play a role in the development of iatrogenic dissection [8]. If only the dissection occurs, it may progress to involve the entire aorta [6,9-11]. Transesophageal echocardiography is a safe and accurate diagnostic method for identifying the extent of dissection and is a useful follow-up tool [2,12]. If the sinus of Valsalva dissection remains localized during catheterization, it tends to resolve spontaneously in the first month [2,6]. Delayed rupture 3 months after PCI, as in this case, is an extremely rare complication. Up until now, no such case and no previous coronary MDCT or MR images have been published. MDCT and MR images are useful in providing a proper 3-D appreciation of the anatomy when planning surgical reconstruction. Manipulation of the guidewire and guiding catheter in the coronary arteries and sinus of Valsalva should always be performed with gentleness and great care.