Transcatheter Arterial Embolization as Treatment for a Life-Threatening Retroperitoneal Hemorrhage Complicating Heparin Therapy

Article information

Abstract

Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage is a distinct clinical entity that can present in the absence of specific underlying pathology or trauma and is typically associated with anticoagulation therapy. We report a case of a 74-year-old female patient with a cerebral infarction related to atrial fibrillation who developed a spontaneous lumbar arterial hemorrhage complicating heparin therapy. The diagnosis was suggested by a computed tomography scan and confirmed by angiography. She was treated successfully with transcatheter embolization.

INTRODUCTION

Heparin is commonly used for prophylaxis against and treatment of acute coronary syndrome, chronic atrial fibrillation, stroke, or various thromboembolic diseases. Unfortunately, hemorrhage, an often serious complication of anticoagulant therapy, is reported in up to 4% of treated patients [1,2]. Treatment for anticoagulant-related hemorrhage is mainly conservative, as it has been thought that the bleed resulted from microangiopathy [3]. However, several studies on the role of angiography for detecting and managing anticoagulant-related hemorrhage have been reported [3,4]. We present a case of lumbar arterial bleeding, secondary to heparin therapy, diagnosed by angiography and successfully treated with transcatheter embolization.

CASE REPORT

A 74-year-old woman was transferred to our cardiac intensive care unit to be evaluated and treated for severe left ventricular dysfunction detected by echocardiographic measurement of the left ventricular ejection fraction in the neurology department of our hospital, where she had been treated with an intravenous bolus of 5,000 units of unfractionated heparin followed by an intravenous heparin infusion of 20,000 units over 24 hours due to an acute cerebral infarction. Her medical history included hypertension and stroke due to an aneurysmal rupture of the left middle cerebral artery that was treated with hemoclipping about 9 years ago. After the hemoclipping, she has suffered intermittent seizures and has been hospitalized many times in the neurology department of our hospital.

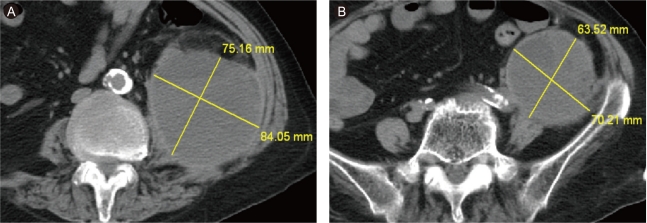

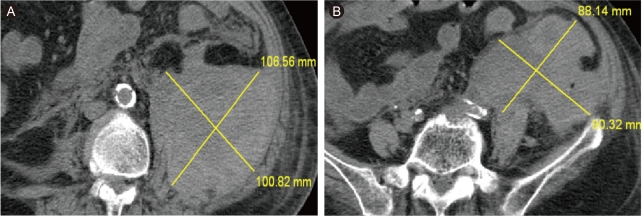

At the time of transfer to Department of Cardiology, she suffered from shortness of breath. Her blood pressure was 80/50 mmHg, heart rate on electrocardiogram monitoring was 130-150 beats/min with irregularity, and respiration rate was > 30 breaths/min under mechanical ventilation. She had distended jugular veins and bilateral rales. Her blood urea nitrogen was 16.2 mg/dL, creatinine was 0.9 mg/dL, and troponin T was 0.116 ng/mL. The median 6-hour activated partial thromboplastin time was 50-70 seconds and remained so throughout heparin infusion. A chest X-ray showed pulmonary edema. Echocardiography revealed apical akinesia and severe hypokinesia of the mid-segment of the left ventricle with severe left ventricular dysfunction. She was treated with amiodarone, diuretics, dopamine, digoxin, and aspirin. The next day, the dopamine was stopped, as blood pressure with sinus conversion became stable; however, all other medications were continued. On the fifth day after transfer, her blood pressure decreased suddenly, and her mentality became altered significantly. Her hemoglobin level decreased from 11.5 to 7.1 g/dL and creatinine increased from 0.8 to 1.9 mg/dL. A noncontrast-enhanced abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan revealed an extensive mixed-density lesion in the left psoas area with extension to the left side of the pelvic cavity (Fig. 1). Our impression was an extensive retroperitoneal hemorrhage (RPH). The clinical condition of the patient deteriorated continuously despite vigorous medical treatment consisting of stopping the anticoagulation therapy, volume resuscitation, transfusion of four units of packed red blood cells, and the administration of vasopressors such as dopamine, dobutamine, and norepinephrine for about 12 hours. We chose transcatheter embolization rather than surgical treatment because of her older age, current heparin and aspirin use, and heart disease. An initial-f lush aortogram showed no definite bleeding focus. Selective catheterization showed extravasation from the left L2 lumbar artery (Fig. 2). The culprit artery was catheterized with a microcatheter and embolized with Contour Emboli® (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA). A post-embolization angiogram did not show any extravasation from the L2 lumbar artery (Fig. 3). A coronary angiogram was performed to distinguish ischemic from nonischemic cardiomyopathy, and no significant stenosis was noted. After embolization, the patient stabilized and was discharged. A follow-up CT scan performed about 2 months after the procedure showed that the size of the hematoma had decreased (Fig. 4).

Computed tomography scan. (A) Huge mixed-density hematoma in the left psoas area. (B) Extension to the left pelvic cavity.

The culprit artery was embolized with Contour Emboli® (arrow). A post-embolization angiogram did not show any extravasation from the L2 lumbar artery.

DISCUSSION

RPH is a well-known complication of anticoagulant therapy that causes significant mortality. The risk factors for anticoagulant-related RPH include specific comorbid diseases (severe heart disease, liver dysfunction, renal insufficiency, hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, and patients on long-term hemodialysis), use of concurrent medications (mainly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents and diuretics), treatment duration, intensity of the anticoagulant effect, and patient age. Little is known about the pathophysiology of spontaneous RPH. It has been hypothesized to be caused by diffuse small vessel arteriosclerosis, whereas others have suggested heparin-induced immune microangiopathy or an unrecognized minor trauma in the microcirculation [5]. The first signs of RPH may include hypotension, abdominal pain, or nerve-compression effects including thigh pain and motor or sensory deficits. A fall in hemoglobin should also raise suspicion of RPH in this setting. An abdominal/pelvic CT is the imaging study of choice for detecting a hematoma formed by RPH. CT permits a precise determination of the site, location, and extension of soft tissue, and an unenhanced study is commonly the initial examination performed for clinically suspected anticoagulant-related RPH [6]. Contrast extravasation on contrast-enhanced CT, which indicates active bleeding, plays significant therapeutic and prognostic roles by predicting failure of conservative treatment and indicating early intervention [3,4]. Transcatheter arterial embolization of RPH caused by trauma or another specific cause is a well-documented and commonly used procedure [7]. However, as the pathophysiology of RPH was formerly believed to be related to vasculopathy of small vessels, angiography traditionally has had no diagnostic or therapeutic role. The mainstay management continues to consist of withdrawal of anticoagulation therapy, correction of the anticoagulation state, volume resuscitation, and supportive measures. Surgical intervention has been considered the only option for uncontrollable hemodynamic collapse. Reports of transcatheter arterial embolization in anticoagulant-related RPH are very scarce, and a review of the literature revealed very few reports of successful cases [8,9]. But Zissin et al. [10] reported that this therapeutic option seemed relevant in anticoagulated patients with large soft tissue hematomas that typically occur spontaneously and are difficult to either predict or prevent. In conclusion, RPH is a relatively uncommon complication of anticoagulation therapy. We experienced a case of RPH caused by anticoagulant-related lumbar arterial bleeding that was successfully treated with transcatheter arterial embolization. In the event of failure of conservative management and the development of hypovolemic shock and when signs of localized active bleeding are present on CT, angiographic evaluation may be helpful to localize the bleed. A subsequent transcatheter arterial embolization is an effective and safe method to control bleeding. Awareness of this optional treatment may improve patient outcomes.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.