Cytomegalovirus Induced Interstitial Nephritis and Ureteral Stenosis in Renal Transplant Recipient

Article information

To the Editor,

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections occur in up to 60% of kidney transplant recipients, with most cases developing between the second and 6 months after transplantation [1]. The clinical manifestations of CMV infection vary widely. Asymptomatic viremia is the most common symptom, although the infection can occasionally invade various organs such as the lung, or the gastrointestinal tract [2]. Likewise, in the urogenital tract, CMV can induce ureteral stenosis by direct invasion of ureter tissue [3]. Involvement of grafted kidneys by CMV occurs frequently. In previous reports, CMV genomes were documented by in situ hybridization techniques in more than 40% of routine graft biopsies [3]. However, significant pathologic changes and allograft dysfunction induced by CMV invasion are rarely observed. Indeed, CMV inclusions in tissue have been reported in less than 1% of renal biopsies when examined by routine light microscopy. Therefore, an alternative method to detect CMV involvement in graft kidneys is required.

In a previous report, pathological CMV nephritis was successfully diagnosed by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and tissue polymerase chain reaction (PCR) [3]. In this regard, the present case illustrates manifestation of CMV nephritis both by ureteral stenosis and CMV interstitial nephritis, diagnosed by IHC stain for CMV. The patient was successfully treated with ganciclovir and immunosuppression reduction. We present this case report with a review of the current literature.

Our patient was a 48-year-old Korean man who suffered from end-stage renal failure attributed to hypertension who had been on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis for 2 years. He had received a living donor renal transplant in January 2010, but the specific record of the donor was not available because the procedure was performed overseas in China. A week after the transplant, when he returned to Korea and visited the hospital, he was put on a dual therapy with tacrolimus and prednisolone with a serum creatinine of 3.1 mg/dL. Tacrolimus was titrated to 4 mg twice a day, mycophenolate mophetil was continued 750 mg twice a day, and prednisolone was added at 25 mg twice a day. Laboratory investigations revealed the following values: white blood cells, 4,840/mm3 with 94.5% polymorphonuclear cells, 1.4% lymphocytes, 4.1% monocytes; hemoglobin 10 g/dL; hematocrit, 29.7%; platelet count, 151,000/mm3; creatinine, 3.1 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 0.45 mg/dL; AST, 8 U/L; ALT, 9 U/L; albumin, 3.1 g/dL; random blood sugar, 133 mg/dL; C-reactive protein, 0.16 mg/dL; and urinary microscopic hematuria.

A Doppler ultrasound of the grafted kidney revealed hydronephrosis without visible obstructive lesions and favorable renal perfusion. The patient underwent percutaneous nephrostomy and showed contrast leakage from the ureterovesical anastomosis. Subsequently, an anterograde double J (DJ) catheter was inserted with a ureteral stent via the right hypogastric posterolateral approach. A Doppler ultrasound performed after the catheter insertion showed complete regression of hydronephrosis of the graft kidney; however, renal function was only partially recovered and the patient's creatinine level hovered around 2.2 mg/dL 2 weeks after catheter insertion.

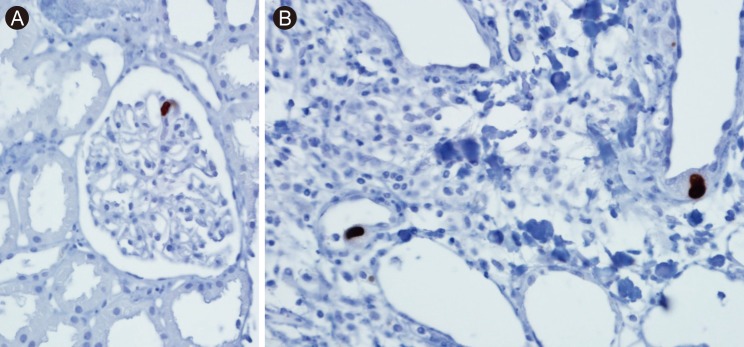

To evaluate the cause of the incomplete recovery of allograft function, a renal biopsy was performed that revealed calcineurin inhibitor toxicity with tubulopathy. Glomerular capillary intracytoplasmic CMV inclusions were seen on IHC stain (Figs. 1 and 2). Real-time PCR for serum CMV yielded 899,766 copies/mL, and CMV antigen was present in the patient's blood on an immune fluorescent test. Otherwise, real-time PCR for BK virus was neither found in urine nor serum, and decoy cell was absent in urine. Furthermore renal biopsy did not show anything on Simian virus (SV) 40 stain. The patient's tacrolimus level was 15.6 ng/mL. The patient was then started on intravenous ganciclovir (2.5 mg/kg q24) and the tacrolimus dose was reduced from 8 to 6 mg/day. Mycophenolate mophetil was discontinued during the period of CMV treatment to decrease the intensity of immunosuppression.

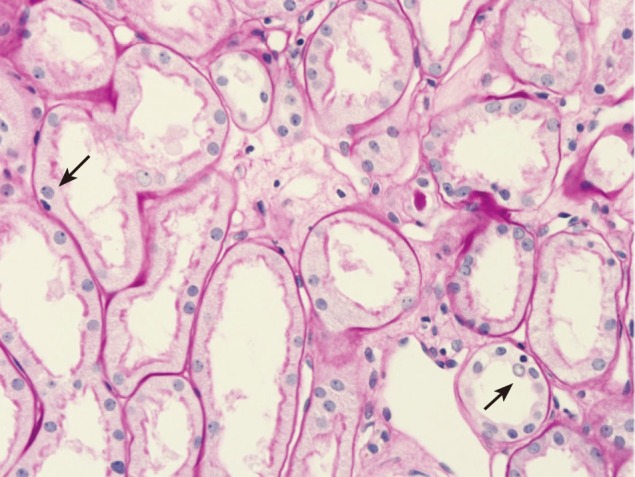

First allograft biopsy. Hematoxylin-eosin staining (× 400) shows tubular vacuolation and anterior medial hyalinosis (arrows).

First allograft biopsy. Immunohistochemical staining. (A) Weak positive (immunohistochemical staining) of cytomegalovirus (CMV) antigen in the endothelium of a glomerular capillary (× 200). (B) Two enlarged capillary endothelial cells containing cytoplasmic inclusions that were positive for CMV antigen by immunohistochemical staining (× 400).

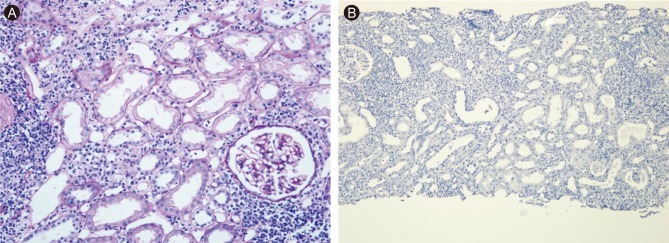

Intravenous ganciclovir was continued for 3 weeks after the biopsy, after which PCR for CMV was 1,031 copies/mL. The patient was maintained on valganciclovir, 900 mg daily and discharged with a serum creatinine level of 2.2 mg/dL. CMV PCR was negative in a subsequent outpatient examination; however, despite complete antiviral therapy, his renal function had deteriorated slightly. Ultrasounds of the graft kidney were normal, and a second biopsy was performed 38 days after the first, the results of which were consistent with acute cellular rejection grade IA with negative IHC for CMV (Fig. 3). The patient was then readmitted and treated with intravenous methylprednisolone (125 mg/day for 3 days) and switched to a tapering dose of oral prednisolone and discharged with a serum creatinine level of 1.41 mg/dL.

Second allograft biopsy. (A) Moderate interstitial infiltrate composed primarily of mononuclear cells involving 25% of renal parenchyma and moderate tubulitis (H&E, × 200). (B) No residual cytomegalovirus antigen by immunohistochemical staining (× 100).

In this case, multiple factors such ureteral obstruction with leakage, calcineurin inhibitor toxicity, and CMV invasion altogether lead to the severe renal dysfunction. Therefore, renal dysfunction was not improved not only by resolution of hydronephrosis after DJ catheter insertion, and it showed improvement with the clearance of CMV viremia. It suggests that CMV invasion may directly affect the renal dysfunction in this case. In previous report, only mild CMV invasion on renal biopsy was associated with renal dysfunction, and it maybe because renal biopsy specimen may not represent the whole status of kidney [4]. Although acute rejection could not have ruled out in the first renal biopsy, serologic and urine study of BKV real time PCR were negative, and considering the allograft biopsy finding, the possibility of the coexistence of BKV nephropathy, or acute rejection is very low. In addition, even though we did not perform any anti-rejection therapy and rather reduce tacrolimus dose, renal function improved.

Direct CMV-related allograft injury, as observed in our patient, is rarely reported in the literature. In a review by Ulrich et al. [4], typical features of CMV infection of the kidney were described as rare histological findings. Renal biopsy may reveal acute interstitial inflammation associated with intranuclear inclusions, suggestive of direct cytopathic effects on tubular epithelial cells by light microscopy. Kashyap et al. [1] analyzed the clinical parameters and pathologic findings in 10 patients with CMV inclusions via renal allograft biopsy with routine 3-µm hematoxylin sections. Histopathologic examinations of the allografts showed interstitial inflammation with tubulitis in seven of 10 (70%) patients, with the remaining three (30%) patients exhibiting viral inclusions without any associated inflammatory response. In our case, with the detection of viral inclusions on light microscopy, IHC stain for CMV antigen confirm the diagnosis of CMV induced allograft tissue injury.

In our case, hydronephrosis was revealed by Doppler ultrasound of the graft kidney in combination with CMV infection. A percutaneous nephrostomy confirmed leakage from the ureterovesical anastomosis, which restored urine flow in the graft kidney, and serum creatinine partially improved. It is possible that ureteral leakage develop as surgical complication. However, severe hydronephrosis suggest that ureteral obstruction is more important problem, because leakage could not cause hydronephrosis. Therefore, we thought that ureteral obstruction may precede ureteral leakge, but the cause-result relationship could not be clarified.

Ducloux et al. [3] reported two cases of renal allograft recipients who experienced simultaneous CMV disease and ureteral stenosis. The association between the development of ureteral stenosis and exposure to CMV is undoubtedly multifactorial, and it has been postulated that CMV may contribute to the disease process during abortive infections, which are characterized by viral-gene expression limited to immediate early gene products without viral replication. Immediate gene products can inhibit p53 functions either by blocking the progression of the cell cycle or initiating apoptosis. Alternatively, tissue damage during permissive infection can lead to ureteral stenosis.

A second biopsy revealed mild improvement of calcineurin inhibitor toxicity and the disappearance of CMV infection, but it showed acute T cell mediated rejection, which was successfully treated by steroid pulse therapy. The development of acute T cell mediated rejection can be explained by two aspects. First, the decrease of immune suppressant can lead to the development of rejection. In this case, we discontinued mycophenolate mofetil and reduce tacrolimus. However, tacrolimus levels were maintained within a therapeutic range, therefore it may not be the direct cause of acute rejection.

Second, CMV can be associated with the development of acute T cell mediated rejection through complex mechanism. Several previous studies have shown that CMV infection is associated with an increased risk of concurrent or subsequent acute rejection [4]. This may be related to the observation that CMV can up-regulate the expressions of histocompatibility antigens in tubular epithelium, thereby making it a better target for cell-mediated immune injury, and that T cells sensitized to CMV antigens within the kidney or at extrarenal sites can release interferon-γ or tumor necrosis factor, thereby leading to parenchymal injury mimicking acute rejection. Cameron et al. [5] reported that patients with tubulointerstitial nephritis (TIN) due to CMV infection have a significantly higher incidence of acute rejection episodes than those with TIN due to other reasons.

In summary, we describe CMV interstitial nephritis combined with ureteral stenosis. Successful clearance of the viral infection by ganciclovir led to improvement in allograft function. A consecutive biopsy confirmed acute cellular rejection maybe triggered by CMV infection, which was recovered with steroid pulse therapy. This case suggest that in cases of allograft dysfunction with significant CMV viremia, we should consider allograft biopsy with CMV IHC stain to differentiate the allograft dysfunction due to direct involvement of CMV in allograft tissue.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.