Tuberculosis of the urachal cyst

Article information

Abstract

Urachal cysts are uncommon. Rarely, these cysts can become infected. Tuberculosis of the urachal cyst is exceedingly rare, with only one case reported previously in the English language literature. Here we report the case of a 23-year-old male who presented with an infra-umbilical mass that turned out to be tuberculosis of the urachal cyst.

INTRODUCTION

Urachal cysts are uncommon and often asymptomatic. They may occasionally become infected and present as an urachal abscess. Tuberculosis of the urachal cyst is extremely rare. Here we report a case that presented with an infra-umbilical mass that turned out to be tuberculosis of the urachal cyst.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old male presented with mild intermittent peri-umbilical pain and low-grade fever for 3 months. There was a history of loss of appetite and weight loss (4 kg over 3 months). The patient's bowel and bladder habits were normal. There was no significant medical or surgical history.

On examination, the patient's vitals were stable and his physical examination was normal except for a well-circumscribed, non-tender mass, about 5 × 5 cm in size, which was palpable in the infra-umbilical area. A routine hemogram, serum biochemistry, liver function, and renal function tests were within normal limits. A chest X-ray revealed no abnormality. Urinalysis revealed occasional pus cells, but the culture was sterile.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was suggestive of a smooth-walled, cystic mass measuring 5 × 5 × 6 cm, located above the bladder (Fig. 1). Fine-needle aspiration cytology revealed necrotic material.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen showing a smooth-walled, non-septate, and cystic lump measuring 5 × 5 cm (arrow).

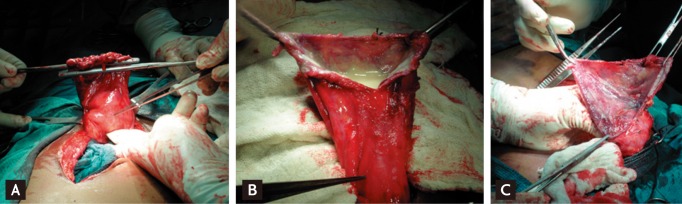

With a clinical diagnosis of an urachal abscess, surgical excision was planned. At surgery, the mass was located in the pre-peritoneal space, just above the bladder. It was filled with white pultaceous material. With gentle blunt and sharp dissection, the mass was separated from the bladder and could be excised en bloc (Fig. 2).

(A) At exploration, the mass was superior to the urinary bladder. (B) White pultaceous material was seen on incising the mass. (C) The mass was separated from the urinary bladder.

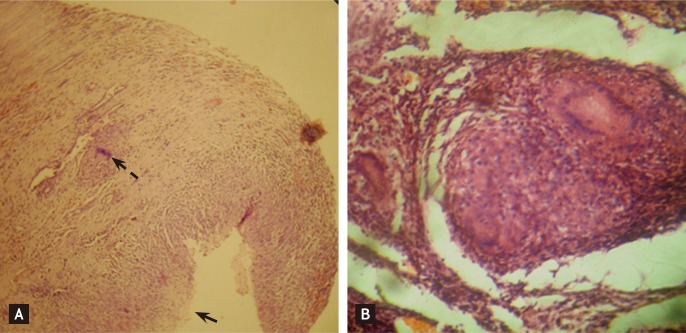

On histopathological examination, urothelium was found along with multiple granulomas, caseation, and epitheloid and Langhans cells, suggestive of urachal tuberculosis (Fig. 3). On the basis of these results, the patient was started on combination anti-tubercular therapy with rifampicin, isoniazid, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide, which were given for 2 months.

(A) Photomicrograph showing the urothelial lining (arrow) and a granuloma (dashed arrow) (H&E, × 10). (B) Multiple epitheloid cells, lymphocytes, caseation, and an occasional Langhans giant cell, suggesting tuberculosis (H&E, × 10).

Culture of the pultaceous material on Lowenstein-Jensen media confirmed the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis; the bacilli were sensitive to isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol. Blood, sputum, and urine cultures performed three times during the post-operative period were sterile.

The patient was then continued on a combination of rifampicin and isoniazid for 4 months, according to national guidelines. The patient completed the treatment and is doing well. Follow-up CT of the abdomen after the completion of anti-tubercular treatment revealed no evidence of disease.

DISCUSSION

The urachus is a remnant of the allantois that runs within the umbilical cord. It normally disappears during the first 4 to 5 months of gestation, ultimately becoming a fibrous cord. Urachal cysts are rare and occur due to incomplete obliteration of the urachus [1,2]. They may rarely become infected and present as an urachal abscess. The most common cause of infection is Staphylococcus aureus [3-6].

Tuberculosis of the urachal cyst is extremely rare; we are aware of only one case described in the English language literature to date. The patient in that case had an old pulmonary scar, suggestive of tuberculosis [7]. In contrast, we could find no evidence of active or old pulmonary tuberculosis in our patient. Blood, urine, and sputum cultures failed to reveal any growth on Lowenstein-Jensen media.

In our country, tuberculosis is an endemic disease that occurs at an early pediatric age, and tubercular infection is a universal phenomenon. A primary lesion, which is most often pulmonary, may not be seen on chest X-ray [8]. We presume that the tubercular infection of the urachal cyst in the case presented was due to re-activation of latent tubercular foci, which were already present in the cyst, due to seeding at the time of primary tuberculosis.

En bloc excision of the abscess is the mainstay of treatment. Medical treatment with anti-tubercular medications must be started along the lines of genitourinary tuberculosis [7].

In conclusions, The possibility of tuberculosis should be considered during the work-up of an urachal abscess.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.