Successful coronary stent retrieval from the ascending aorta using a gooseneck snare kit

Article information

Abstract

Coronary stent dislodgement is a rare complication of percutaneous coronary intervention. We report a case of stent dislodgement in the ascending thoracic aorta. The stent was mechanically distorted in the left circumflex artery (LCX) while being delivered to the proximal LCX lesion. The balloon catheter was withdrawn, but the stent with the guide wire was remained in the ascending thoracic aorta. The stent was unable to be retrieved into the guide catheter, as it was distorted. A goose neck snare was used successfully to catch the stent in the ascending thoracic aorta and retrieved the stent externally via the arterial sheath.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary stent dislodgement is a rare complication of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and is often associated with significant morbidity [1,2]. Stent loss may occur more often in severely calcified or angulated lesions [3,4]. Stent migration may lead to severe complications, it may embolize in the coronary circulation, and it may cause embolic cerebrovascular events or peripheral embolization [5]. Retrieval of a dislodged stent can be performed either percutaneously or surgically [6]. Various devices and techniques can be used: a small balloon catheter, a snare loop, the two-wire technique, grasping forceps, and basket retrieval devices [7,8]. The snare loop is relatively safe and sometimes highly effective [9]. We report a rare case of stent dislodgement in the ascending thoracic aorta with a guide wire during stent delivery to a proximal left circumflex artery (LCX) lesion.

CASE REPORT

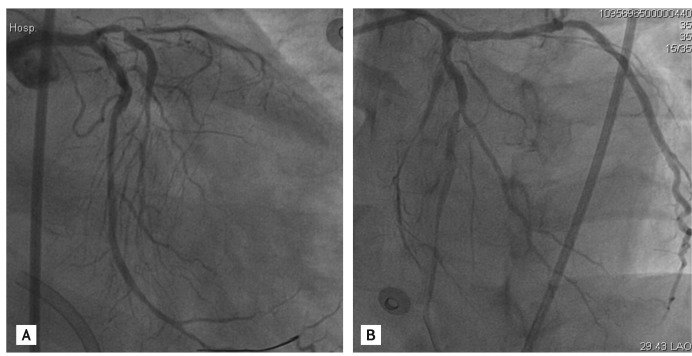

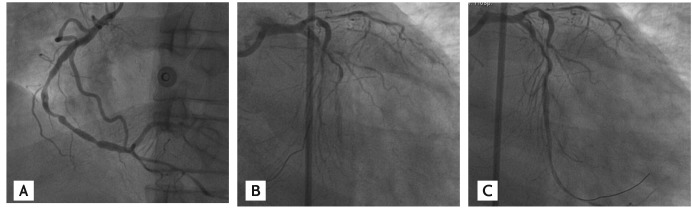

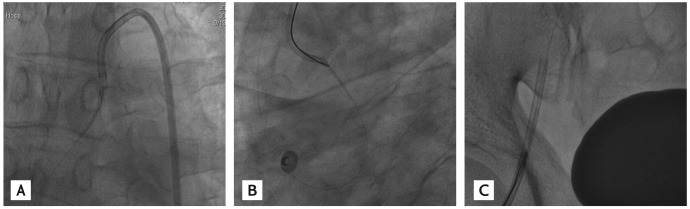

A 61-year-old male patient was admitted to the emergency room with chest pain secondary to a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. The first symptoms occurred 7 days prior to hospitalization and the patient had been experiencing chest pain for 30 minutes at the time of admission. His troponin I was 1.20 ng/mL (normal range, 0.00 to 0.16) and creatine kinase-myocardial band was 10.0 ng/mL (normal range, 0.0 to 5.3). Electrocardiography showed ST segment depression in V4-6. He was a cigarette smoker. Diagnostic coronary angiography performed via the right femoral artery showed total occlusion of the proximal LCX as the culprit lesion, a chronic total occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD), and a complex 95% subtotal occlusion of the proximal right coronary artery (RCA) with bridging collateral circulation (Fig. 1). Coronary angiography revealed a collateral circulation from septal branches to the distal RCA (Rentrop grade III) and from the right ventricular branch to the LAD (Rentrop grade III) (Fig. 1). The patient and his family refused a coronary artery bypass graft. A 3.0 × 28-mm Xience stent (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was implanted in the proximal RCA (Fig. 2). Then, a 7-French JL4 guide catheter (Medtronic, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) was used to engage the left main coronary artery and a 0.014-inch guide wire (Abbott Vascular) was placed in the distal LCX. The proximal segment of the LCX was predilated initially using a 1.5 × 15-mm Ryujin balloon (Termo, Tokyo, Japan) to 10 atm, after the angiography showed severe tortuosity of the LCX lesion (Fig. 2). The LCX lesion was predilated additionally with a 2.0 × 20-mm Ryujin balloon to 10 atm (Fig. 2). A 2.5 × 28-mm Xience stent was introduced into the proximal LCX; however, it could not be delivered to the target lesion despites multiple attempts to advance the stent distally. We felt that further aggressive predilation was required and attempted to retrieve the stent into the guide catheter. The stent became detached totally from the stent balloon. The procedure was complicated by stent dislodgement in the ascending thoracic aorta with the guide wire (Fig. 3). The dislodged stent could not be retrieved by a small balloon technique or a double-wire technique. A gooseneck snare (St. Jude Medical, Sylmar, CA, USA) was passed into the guide catheter and the stent was snared successfully (Fig. 3). The snare and stent could not be withdrawn into the guide catheter, and consequently, the snared stent with the guide catheter was removed from the femoral artery sheath (Fig. 3). Close examination of the retrieved stent revealed severe distortion, which could explain the difficulty encountered while attempting to retrieve it into the guide catheter (Fig. 4). We exchanged the JL4 guide catheter for an extraback-up (Medtronic). The proximal LCX was additionally dilated using a 2.5 × 20-mm Ryujin balloon to 14 atm. The rest of the PCI was completed with the implantation of a 2.5 × 28-mm Xience stent at the proximal LCX. The final result showed good stent deployment and no complication (Fig. 5). After stent implantation at the proximal LCX, ST segment depression in V4-6 disappeared on electrocardiography. Two days later, he underwent successful PCI to the totally occluded proximal LAD with a 3.0 × 28-mm Xience stent (Fig. 5). The patient was discharged on the fifth day in good condition.

Diagnostic coronary angiography shows total occlusion of the proximal left circumflex artery as a culprit lesion, (A) a chronic total occlusion of the proximal left anterior descending artery (LAD) and (B) a complex 95% subtotal occlusion of the proximal right coronary artery with collateral circulation from the right ventricular branch to the LAD.

(A) A 3.0 × 28-mm Xience stent (Abbott Vascular) was implanted in the proximal right coronary artery. (B) The proximal segment of the left circumflex artery (LCX) was predilated initially using a 1.5 × 15-mm Ryujin balloon (Termo) to 10 atm. (C) The LCX lesion was predilated further with a 2.0 × 20-mm Ryujin balloon to 10 atm.

(A) The dislodged stent with guide wire seen in the ascending thoracic aorta. (B) A gooseneck snare (St. Jude Medical) was passed into the guide catheter and the stent was snared successfully. (C) The snared stent together with the guide catheter was removed from the femoral artery sheath.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of stent dislodgement is uncommon nowadays, with precise mechanical crimping of the stent onto the balloon varying between 0.32% and 8% [1,2]. Dislodgement of a stent can be secondary to extreme coronary angulation, highly calcified coronary arteries, inadequate coronary artery predilation, and direct stenting [3,4]. In this case, the stent distortion was likely secondary to the highly calcified LCX, inadequate predilation, and the inadequate coaxiality of the JL guide when attempting to retrieve the uncrossable stent. Percutaneous stent retrieval can be achieved using a number of techniques, including a small balloon technique, a double wire technique, or a loop snare [7,8]. The choice of retrieval device and technique should be specific to each case and to operator experience. The decision must be taken in light of the location of the stent, the type of stent, and its deployment status. A snare loop is relatively safe and easy to use. It has a low rate of complications and appears to be effective [9]. In our case, a snare loop appeared to be the best method of retrieval, because our lost stent had not been deployed and rode on a guide wire in the ascending thoracic aorta. Stent loss can occur due to arterial tortuosity and calcification, direct stenting, and inadequate coaxiality of the guide catheter; thus, adequate predilation with a balloon catheter may help prevent stent loss. Also, when resistance is encountered during undeployed stent withdrawal, removal of the entire system including the stent, wire, and guide catheter may help prevent stent dislodgement [1]. Nowadays, with the development of intracoronary procedures, stent loss and dislodgement occur rarely. Nevertheless, every catheterization laboratory should be equipped with a set of instruments for intravascular foreign body retrieval and interventional cardiologists should be familiar with these retrieval methods and techniques.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.