The effects of secondhand smoke on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in nonsmoking Korean adults

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Smoking is widely acknowledged as the single most important risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, the risk of COPD in nonsmokers exposed to secondhand smoke remains controversial. In this study, we investigated the association of secondhand smoke exposure with COPD prevalence in nonsmokers who reported never smoking.

Methods

This study was based on data obtained from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (KNHANES) conducted from 2008 to 2010. Using nationwide stratified random sampling, 8,596 participants aged ≥ 40 years of age with available spirometry results were recruited. After selecting participants who never smoked, the duration of exposure to secondhand smoke was assessed based on the KNHANES questionnaire.

Results

The prevalence of COPD was 6.67% in participants who never smoked. We divided the participants who had never smoked into those with or without exposure to secondhand smoke. The group exposed to secondhand smoke was younger with less history of asthma and tuberculosis, higher income, and higher educational status. Multivariate logistic regression analysis determined that secondhand smoke did not increase the prevalence of COPD.

Conclusions

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of COPD between participants who had never smoked with or without exposure to secondhand smoke in our study. Thus, secondhand smoke may not be an important risk factor for the development of COPD in patients who have never smoked.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a lung disease characterized by irreversible airflow limitation due to airway inflammation and lung parenchymal damage. COPD is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality worldwide, resulting in serious social and economic burden [1,2]. COPD is caused by multiple external factors including smoking, air pollution, socioeconomic status, and respiratory infections; and host factors including genetic factors, age, gender, airway hypersensitivity, and lung growth [3].

Smoking is the single most important risk factor for development of COPD; therefore, the subjects in most COPD studies are current or ex-smokers. Approximately one-fourth to one-third of COPD patients have never smoked [4,5,6,7]. As a result, studies on nonsmoking COPD patients have gained attention recently [3].

We conducted this study to investigate the degree of secondhand smoke exposure in participants who have never smoked and the characteristics of COPD in nonsmokers to assess the possible association of secondhand smoke with the prevalence of COPD.

METHODS

Study design

We analyzed data obtained from the second year of the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) IV (2008) to the first year of KNHANES V (2010). For details refer to previous studies regarding COPD that made use of KNHANES data [8,9].

Setting

The KNHANES is a national cross-sectional survey and a population-based epidemiological survey of health and nutrition with a stratified multistage clustered probability design, conducted by the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea. KNHANES includes four components: the Health Interview Survey, the Health Behavior Survey, the Health Examination Survey, and the Nutrition Survey.

Questionnaire and procedures

Standardized questions elicited self-reported information on demography, smoking status, family income, education status, history of asthma and tuberculosis, and respiratory symptoms. Family income was classified as low, moderate-low, moderate-high and high. Education status was classified as below elementary, middle school, high school, and college or above. A previous history of asthma or tuberculosis was confirmed if the patient responded 'yes' regarding whether a physician had ever diagnosed asthma or tuberculosis or if they currently suffered from asthma or tuberculosis. Secondhand smoke exposure was assessed by self-reported hours of exposure per day at the workplace and home. A forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) < 70% without a bronchodilator response test was defined as COPD in subjects ≥ 40 years of age. The urine cotinine level was measured by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry using the Perkin Elmer Clarus600T instrument (PerkinElmer, Turku, Finland).

Participants

Subjects were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were ≥ 40 years of age, had valid spirometry results, and had never smoked, defined as someone who had not smoked a cigarette during their lifetime.

Statistical analysis

To adjust for unequal probabilities of selection and to account for nonparticipation, all estimates were calculated on the basis of the sampling weight. Comparisons between groups were performed using the chi-square test or linear regression analysis. Multivariate regression was performed for the analysis of the association of secondhand smoke exposure and COPD prevalence after adjustment for age, gender, previous diagnosis of asthma or tuberculosis, family income, and education status. All values are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using the SAS version 8.0 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was considered at values of p < 0.05.

RESULTS

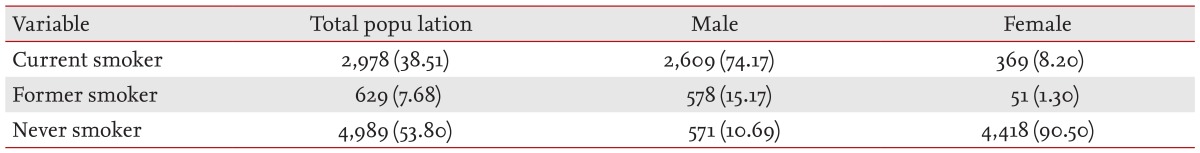

Smoking status stratified by gender and prevalence of COPD in participants who had never smoked

The total number of eligible participants was 8,596. The proportion that had never smoked was 53.80% among Korean adults ≥ 40 years of age (n = 4,989; male 10.69%, female 90.50%) (Table 1). The prevalence of COPD among those that had never smoked was 6.67% (n = 323), and was higher in males (12.96%) than in females (5.77%). Among the subjects exposed to secondhand smoke, the prevalence of COPD was lower than that among those not exposed to secondhand smoke (4.34% vs. 7.80%), and this trend was similar regardless of gender (male, 6.73% vs. 16.71%; female, 3.94% vs. 6.63%, respectively) (Table 2).

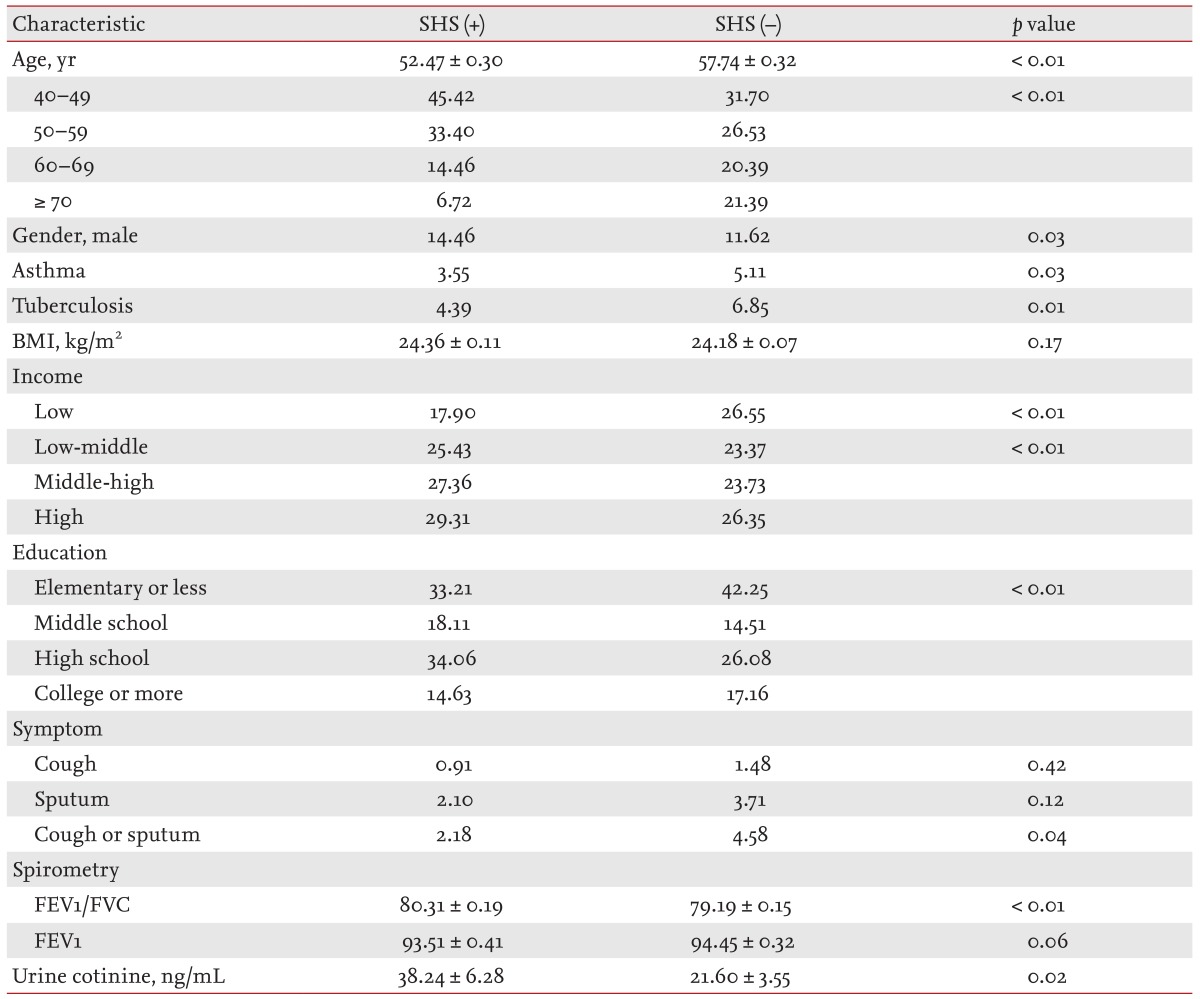

Comparison of baseline characteristics among participants who had never smoked based on secondhand smoke exposure

Of the participants that had never smoked, 32.54% had been exposed to secondhand smoke. When compared to those without secondhand smoke exposure, the subjects with secondhand smoke exposure had a lower mean age (52.47 vs. 57.74, p <0.01), higher proportion of male gender (14.46% vs. 11.62%, p = 0.03), lower previous history of asthma (3.55% vs. 5.11%, p = 0.03) and tuberculosis (4.39% vs. 6.85%, p = 0.01), greater family income (lowest quartile, 17.90% vs. 26.55%, p < 0.01), higher education status (elementary school or less, 33.21% vs. 42.25%, p < 0.01), and higher urine cotinine level (38.24 ng/mL vs. 21.60 ng/mL, p = 0.02) (Table 3).

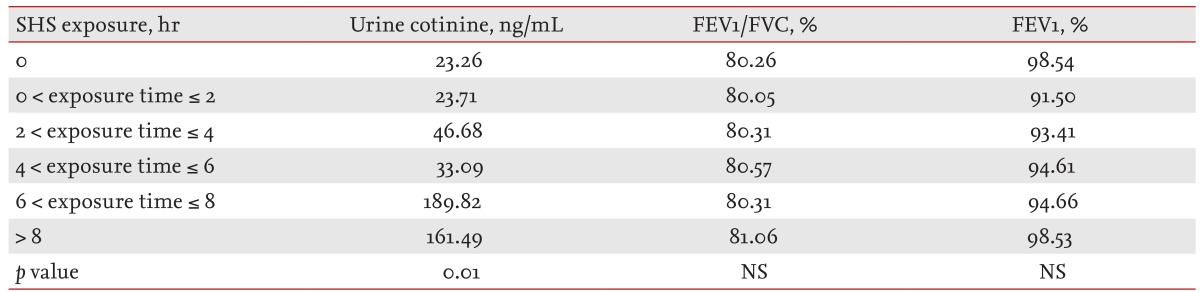

Urine cotinine levels and pulmonary function according to secondhand smoke exposure

In participants who had never smoked, the urine cotinine level increased significantly with duration of exposure to secondhand smoke (≤ 2 hours vs. > 8 hours; 23.71 ng/mL vs. 161.49 ng/mL; p = 0.01). However, there was no difference in FEV1/FVC and FEV1 according to secondhand smoke exposure time (Table 4).

Risk of COPD according to secondhand smoke exposure

In the group exposed to secondhand smoke for > 6 hours per day, the odds ratio for COPD prevalence was 1.75 (0.47 to 6.59, p = 0.41) after adjusting for variables such as age, gender, previous diagnosis of asthma and tuberculosis, family income and education status. Therefore, there was no significant association between secondhand smoke and COPD prevalence (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

Secondhand smoke is known to increase the incidence of heart disease, lung cancer, and asthma. It also causes respiratory symptoms such as cough and phlegm [10,11]. In our study, we investigated the relationship between secondhand smoke exposure and COPD in Koreans who had never smoked and the epidemiological differences between groups that were or were not exposed to secondhand smoke. Most participants ≥ 40 years of age who had never smoked were female, which reflects the lifestyle of the Korean population; the male lifetime smoking rate is ~90%. Considering that smoking is the single most important COPD risk factor, the low prevalence of COPD in subjects exposed to secondhand smoke was unexpected. These results may be attributable to the characteristics of patients not exposed to secondhand smoke, who were generally older had had a higher rate of a history of asthma and tuberculosis, lower income, and lower education status. Moreover, previous studies have reported that females are more susceptible to COPD; a greater number of female participants in our study population were not exposed to secondhand smoke.

Urine cotinine is a metabolite of nicotine used as an indicator of secondhand smoke exposure that increases over time following exposure [12]. In our study, urine cotinine levels were correlated with secondhand smoke exposure, confirming the reliability of our results. However, there was no significant association between secondhand smoke exposure and spirometry results. Furthermore, we found no significant association between secondhand smoke and COPD prevalence by multivariate analysis.

Cigarette smoke contains approximately 4,000 toxic substances, such as oxidative gas, heavy metals, cyanide, and at least 50 carcinogens [12]. These hazardous substances are emitted into the air in exhaled smoke [13]. Several previous studies have reported an association between COPD with exposure to passive smoking during childhood and respiratory symptoms in adulthood [14]. Moreover, passive smoking was associated with poorer health status and a greater risk of COPD exacerbation [15]. A few studies have contradicted the correlation between secondhand smoke exposure and COPD prevalence. For example, analysis of approximately 6,000 Chinese subjects who had never smoked showed that passive smoking increased the risk of COPD and respiratory symptoms [16]. In contrast, a health survey performed in England indicated that increased passive smoking exposure was independently associated with an increased risk of COPD in the general population, but did not increase the risk of COPD in those that had never smoked [17].

Our study had several limitations. First, it was of a cross-sectional design so we are unable to demonstrate a causal relationship between secondhand smoke and COPD. However, the strength of this study was the systematic analysis of the domestic status of those participants who had never smoked that were exposed to secondhand smoke using a nationwide Korean database. Second, we investigated the presence of secondhand smoke exposure using questionnaires only. We accounted for the possibility of recall bias due to the characteristics of this cross-sectional survey by assessing the urine cotinine level, thereby increasing the reliability of the results. However, it is important to note that the urine cotinine level reflects nicotine absorption for 2 to 3 days only and cannot be used to assess long-term exposure. Third, we were unable to obtain information on the duration of exposure to secondhand smoke due to the simplicity of the survey questions. Chronic diseases such as COPD have been associated with continuous and long-term exposure to risk factors; therefore, the duration and total amount of exposure are important variables. If subjects had been asked more specific questions regarding their recent exposure, the answers would likely focus on more recent exposures that would be reflected in the survey and urine cotinine level. Fourth, we identified significant differences in age, gender, previous diagnosis of asthma or tuberculosis, income, and education status based on the presence or absence of secondhand smoke exposure in those participants who had never smoked. We did not investigate the effect of each variable on the risk of COPD in those participants who never smoked, although these variables are known COPD risk factors in never smokers [3]. Further investigation of the correlation between those variables and the risk of COPD would yield more accurate information regarding the characteristics of COPD in nonsmokers.

In summary, COPD prevalence was higher in a Korean population ≥ 40 years of age without secondhand smoke exposure; however, this might reflect epidemiological differences between the two groups rather than effects of secondhand smoke. A prospective large cohort study should be performed to confirm the impact of secondhand smoke on the prevalence of COPD among those that have never smoked.

KEY MESSAGE

The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was 6.67% in participants who had never smoked.

The prevalence of COPD was lower among subjects exposed to secondhand smoke than among those not exposed to secondhand smoke (4.34% vs. 7.80%).

Risk factors other than secondhand smoke exposure might be important for the development of COPD in patients who have never smoked.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.