Graves' disease presenting with acute renal infarction

Article information

To the Editor,

Hyperthyroidism is associated with increased plasma levels of procoagulants and antifibrinolytic clotting factors such as fibrinogen and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 [1,2]. Similarly, thyrotoxicosis is associated with the occurrence of arterial thrombosis that is primarily due to atrial arrhythmias; the overall incidence of thromboembolism varies from 8% to 40% [3]. Thrombosis is often observed in patients with thyrotoxicosis but there are few reports of arterial thrombosis in conjunction with thyrotoxicosis that are independent of atrial arrhythmias. The present study is a case report of a patient with Graves' disease who presented with a renal infarction without atrial fibrillation.

A 54-year-old man visited our emergency department due to the sudden onset of left flank pain for 30 minutes that was accompanied by dysuria in the absence of other symptoms of pyelonephritis in conjunction with neck enlargement and eyeball protrusion. The patient did not have a medical history of diabetes, hypertension, or cardiovascular disease but he had a 10 pack-per-year history of smoking. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed sinus tachycardia but his chest X-ray was unremarkable. His vital signs were as follows: blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg, heart rate of 108 beats per minute, respiration rate of 22 breaths per minute, and body temperature of 36.5℃. His laboratory findings were as follows: urinary analysis of 5 to 9 red blood cells per high power field, +1 proteinuria, a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 0.01 µU/mL (normal range, 0.55 to 4.78), a free thyroxine level of 28.33 pmol/L (normal range, 11.5 to 22.7), and a TSH-binding inhibitory immunoglobulin level of 40.00 IU/L (normal level, 1.75 or less). Coagulation tests, including prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time, were performed while the patient was in the emergency room and were within normal ranges. In addition, the patient's levels of Factor VIII, von Willebrand factor, antithrombin III, fibrinogen, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 were also assessed to screen for coagulation and fibrinolytic system disorders. All levels were within normal ranges and further tests for antiphospholipid antibodies, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, which are associated with vasculitis, were negative.

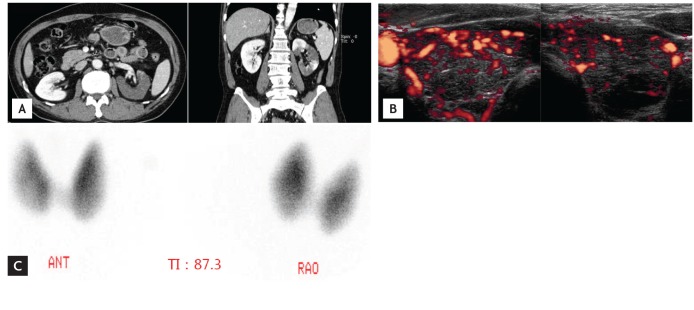

Initial Holter monitoring (24 hours) revealed sinus tachycardia but the patient's echocardiogram findings were normal. An enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a hypoechoic lesion with a clear wedge-shaped margin on the left kidney and a thrombus in the left renal artery (Fig. 1A). The renal infarction was diagnosed based on the symptoms of the patient and typical CT findings and he was treated with intravenous unfractionated heparin infusions. A thyroid ultrasonography revealed increases in the size and vascularity of both thyroid glands (Fig. 1B) and a technetium-99m thyroid scan was compatible with a diagnosis of Graves' disease (Fig. 1C). The patient was initially treated with methimazole and was switched to warfarin therapy after 5 days of heparin infusions. A second round of Holter monitoring (24 hours) after 1 week showed nonspecific findings and a subsequent ECG showed a normal sinus rhythm.

(A) An enhanced abdomen computed tomography scan showing a left renal infarction in the transverse view (left) and the coronal view (right). (B) Thyroid ultrasonography revealing increases in the size and vascularity of both lobes. (C) A technetium-99m thyroid scan showing diffuse increased uptake in both lobes. ANT, anterior; TI, thyroid index; RAO, right anterior oblique.

Hyperthyroidism is associated with a hypercoagulable state and is thought to increase the risk of venous thrombosis [2]. However, the relationship between thyroid function and the risk of venous thrombosis has yet to be fully explored. Thyrotoxicosis shifts the haemostatic balance of an individual towards a hypercoagulable and hypofibrinolytic state [2], but unlike venous thrombosis, the arterial embolisms that are associated with thyrotoxicosis typically result from atrial arrhythmias. Patients with hyperthyroidism frequently present with atrial fibrillation, and its incidence is approximately 10% to 25% for all patients with thyrotoxicosis [3]. The overall rate of systemic embolisms is 8% to 40% in patients with thyrotoxic atrial fibrillation [3], but as in the present case, the presence of arterial thromboembolism in thyrotoxic patients without cardiac arrhythmia is very rare and not fully characterized. Only seven cases of acute cerebrovascular ischemic disease have been reported [1] and in some of these instances, including the present case, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or vasculitis that may contribute to embolic phenomena could not be entirely excluded.

In the present case, the patient presented with a renal infarction during the course of thyrotoxicosis that was caused by hyperthyroidism induced by Graves' disease. Although the relationship that likely exists between arterial embolisms, particularly renal infarctions, and hyperthyroidism needs to be clarified, the present case suggests that uncontrolled thyrotoxicosis is associated with a risk of renal infarction.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.