Pulmonary Nodular Lymphoid Hyperplasia Associated with Sjögren's Syndrome

Article information

Abstract

Pulmonary nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH) is a term first suggested by Kradin and Mark to describe one or more pulmonary nodules or localized lung infiltrates consisting of reactive lymphoid proliferation. To date, there have been only a few cases of pulmonary NLH reported associated with autoimmune disorders. There is no case of NLH associated with Sjögren's syndrome from Korea in the medical literature. A 56-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with cough productive of sputum and chest tightness. The Computed tomography scans of the chest revealed multiple and well-defined peribronchiolar nodular opacities. A video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) biopsy was performed and the nodular opacity in the lung parenchyma was pathologically confirmed as NLH. Through meticulous review of patient's record, we found that she had been suffering from dry eye and dry mouth. The symptoms suggested Sjögren's syndrome, which was confirmed by specific laboratory tests including the Schirmer test, anti-nuclear antibody and anti-Ro/La antibody. The patient is followed regularly and has no further progression of symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

Sjögren's syndrome is a chronic inflammatory autoimmune disease that is characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of the exocrine glands resulting in the sicca syndrome1-3). Several pulmonary manifestations associated with primary Sjögren's syndrome have been reported such as airway disease, interstitial lung disease, alveolar disease, lymphoproliferative disease, and other pleural abnormalities1, 3). Although variety of lung diseases are associated with Sjögren's syndrome, lymphoma or pseudolymphoma should be suspected when lung nodules or hilar and/or mediastinal lymphadenopathy are identified on chest radiographs. Pseudolymphoma is often considered to include mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, NLH and other low-grade lymphoid diseases4, 5). However, the differentiation between NLH and other entities is difficult. Therefore, surgical biopsy and immunohistochemical evaluation is often necessary6). Here we report a patient with biopsy proven pulmonary NLH associated with Sjögren's syndrome.

CASE REPORT

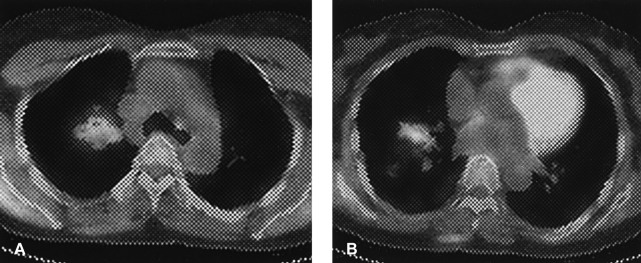

A 56-year-old woman presented with chest tightness, chronic cough and sputum that was present over the past three years. Her symptoms did not subside with medical treatment at local hospitals. The patient was referred to our hospital. The chest plain radiograph and chest CT scan showed multiple and relatively well-defined, multifocal peribronchiolar nodules (Figure 1). There were no contributory findings in the medical and social history.

Numerous parenchymal nodules in both upper lobe lung fields (A) and irregular thickening of the right major fissure (B).

The physical examination showed a blood pressure of 100/70 mmHg with a pulse rate of 78/min, respiratory rate 27/min, body temperature 36.8℃. The patient appeared well. The sclera was not icteric, the abdomen was flat and there were no gross abnormalities.

Laboratory findings at the first visit showed: the blood cell count was 5,750/mm3, hemoglobin 12.7 g/dL, hematocrit 37.3%, and the platelet count was 298,000/mm3. The serum biochemical findings were an AST of 20 IU/L, ALT 13 IU/L, ALP 182 IU/L, LDH 386 IU/L, total bilirubin 0.86 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.10 mg/dL, total protein 7.9 g/dL, albumin 4.0 g/dL, BUN 15 mg/dL, creatinine 0.6 mg/dL, total cholesterol 184 mg/dL, uric acid 4.9 mg/dL, Ca 9.3 mg/dL, P 4.4 mg/dL, Na 140.8 mEq/L, K 4.1 mEq/L, and Cl 108.7 mEq/L.

The pulmonary function testing showed a normal predicted value. The bronchoscopic findings were not specific. Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative. The AFB stain, AFB culture and M. tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (RCR) of the bronchoscopic washing fluid was negative. The patient was admitted to our hospital for further evaluation.

Follow-up chest CT showed similar peribronchiolar nodules; the noted consolidations persisted at both the upper and middle lobes of the lung (Figure 2). The 18FDG-PET CT scan showed mild increased uptake consistent with glucose metabolism the peak SUV was 1.5 at the RUL and 1.6 at the RML (Figure 3). In the 2 hour delayed views, the peak SUV was 1.6 at the RUL and 1.2 at the RML. Percutaneous CT-guided needle aspiration biopsy was performed targeting the consolidation area in the RML. However, the biopsy was insufficient for a diagnosis. Therefore, a VATS biopsy was planned of the consolidation area in the RML.

Follow-up chest CT 2 months after the initial visit reveals peribronchial consolidation (A), and marked bronchial wall thickening (B) in the right middle lobe lung field.

18FDG PET-CT scan shows increased glucose metabolism and peribronchial consolidation in the right upper lobe (A) and middle lobe (B).

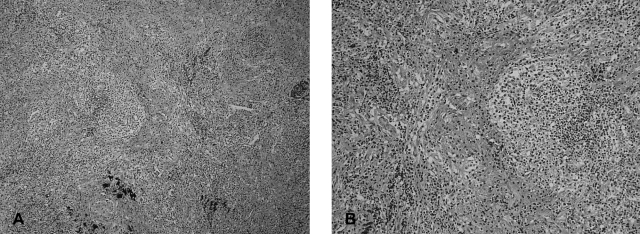

The gross appearance of the involved lung appeared consolidated. The microscopic findings showed that the alveolar walls rather than the air spaces were affected; they were expanded by the interstitial infiltrate. The inflammatory infiltrates were prominent around the bronchovascular bundles and formed rounded nodular aggregates around small intralobular vessels. The infiltrates consisted of predominantly small lymphocytic cells with some mixture of plasma cells and a few larger mononuclear cells. Surrounding parenchyma occasionally revealed lymphoid follicles (Figure 4). Immunohistochemically, the infiltrate was predominantly composed of T cells (CD45RO positive); there were only focal peribronchiolar or paraseptal collections of B cells (CD20 positive). Molecular studies were performed to rule out MALT lymphoma. Amplification of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene by PCR showed a polyclonal pattern of reactivity (Figure 5). The pulmonary nodular opacities were confirmed as nodular lymphoid hyperplasia histologically.

The Hematoxylin-eosin stain showed peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltration and bronchiolar damage (A, ×100), fibrotic narrowing is seen in small vessels and peribronchiolar fibrosis is commonly associated with lymphocytic infiltration (B, ×200).

In the immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement analysis, a positive control with a monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain pattern of a lymphoma patient. The heavy chain rearrangement in our patient shows a polyclonal pattern of reactivity, different from the positive control (M: molecular marker, PC: positive control, NC: negative control, bp: base pair).

We investigated the possibility of an association between these findings and connective tissue disease, immunodeficiency conditions or hypersensitivity reactions. The patient had complained of mild dry eyes and mouth. The ANA was positive (1:640, speckled type), and the anti-La antibody was positive. In addition, the Schirmer test was positive. The findings were consistent with the diagnosis of Sjögren's syndrome. The patient had pulmonary NLH associated with Sjögren's syndrome. Pilocarpine was prescribed for dry eye. The patient is followed regularly and has no progressive symptoms.

DISCUSSION

Sjögren's syndrome is an autoimmune disease characterized by keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostomia7). Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and xerostomia is caused by lymphocytic infiltration of lacrimal and salivary glands and associated pulmonary findings are common. The frequency of lung involvement in patients with Sjögren's syndrome is difficult to ascertain and varies according to criteria used for the diagnosis. The pulmonary manifestation associated with Sjögren's syndrome include xerotrachea, bronchial sicca, obstructive small airway disease, interstitial lung diseases, lymphoinfiltrative or lymphoproliferative lung diseases, and other pleural abnormalities8, 9). Lymphoinfiltrative or lymphoproliferative lung diseases include follicular bronchiolitis, pseudolymphoma and lymphoma, as well as lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia. Differentiation of these lung diseases is difficult. Therefore, surgical confirmation is necessary6).

Pathologically, pseudolymphoma is characterized by infiltration of mature lymphocytes and plasma cells without involvement of lymph nodes10). Reactive follicles and germinal centers are present within the lesion. However, it is difficult to determine whether these findings are due to a benign reactive hyperplasia or a malignancy. The findings of morphologically low-grade lymphoid proliferation with reactive germinal centers in the lung may represent low-grade B cell lymphomas of MALT5). Immunohistochemical studies can be used to help differentiate the etiology of these findings. NLH is considered a benign lesion composed of polyclonal lymphocytes. However, MALT lymphoma is consists of monoclonal lymphocytes4, 5, 10). Pseudolymphoma includes MALT lymphoma, NLH and other low-grade lymphoproliferative diseases4, 5).

NLH can be found in any age group, but the majority of cases occur between ages 50 and 69. Abbondanzo et al reported 14 cases with a slight female predominance and median age of 65 years (range 19-80)5). Most patients are asymptomatic but some present with cough, sputum or dyspnea4). Association with autoimmune disorders such as Sjögren's syndrome has been suggested in some cases. However, there is no previous case reported in Korea11).

The most frequent radiographic finding of NLH is a solitary pulmonary nodule. The chest x-ray in approximately 65% of cases of nodular lymphoid hyperplasia shows a solitary nodule that typically measures 2 to 4 cm in diameter12). Multiple lesions have been reported in 36% of patients5). Abnormal lesions on the chest radiograph, are either discrete nodules or ill-defined nodular opacities. Air-bronchograms are often noted. On CT scan, lesions are discrete pulmonary nodules or ill-defined nodular opacities associated with air-bronchograms and vascular involvement2, 11).

NLH of the lung has several constant pathological features. Most cases are solitary, but two or three nodules may be present. The lesion is characterized by circumscribed masses of lymphoid tissue with numerous reactive germinal centers6, 12). The germinal centers typically have well preserved mantle zones and plasma cells prominent within their interfollicular areas. Immunohistochemical analysis shows a mixture of B and T cells with germinal centers expressing CD20 (B cell type) and interfollicular lymphocytes expressing CD3, CD43 and CD5 (T cell type). A polyclonal pattern of reactivity on immunohistochemical staining is consistent with the diagnosis of NLH6).

In our case, the patient was referred to our hospital due to mild respiratory symptoms and abnormal radiological findings including bronchial wall thickening, irregular peribronchial consolidation and multiple ill-defined nodules in both lung fields. VATS was performed and part of the lesion resected. A reactive lymphoid follicle with germinal centers was noted, but lymphoepithelial reaction was not seen on pathology. The immunohistochemical studies showed mixed cells with germinal centers and a polyclonal cell pattern, this confirmed the diagnosis of NLH. The patient is doing well with no further clinical manifestations.

Notes

This work was supported by Pusan National university Hospital clinical Research Grant (2005).