Acquired Hemophilia Successfully Treated With Oral Immunosuppressive Therapy

Article information

Abstract

Acquired hemophilia is a rare disorder associated with serious bleeding in nonhemophilic patients. We had a 40-year-old woman who was diagnosed as acquired hemophilia with a factor VIII inhibitor level of 27.5 BU/mL. She was presented with gross hematuria and severe right shoulder pain, and was successfully treated with daily oral cyclophosphamide and prednisone for 2 weeks. After the remission, the doses of prednisone and cyclophosphamide were slowly decreased and she remained in complete remission without further bleeding episodes.

INTRODUCTION

Acquired hemophilia is an extremely rare disorder characterized by the spontaneous acquisition of autoantibodies against factor VIII coagulant proteins (FVIII:C) in nonhemophilic patients1). Patients are often presented with serious and fatal bleeding unresponsive to factor VIII infusion2). Although various treatment methods have been described, there are still challenges to decrease or eliminate factor VIII inhibitors in the acquired hemophilia2). Recently, some investigators suggested that oral cyclophosphamide and prednisone without empirical factor VIII therapy may be useful for patients with high titers of factor VIII inhibitors3,4).

We report a case of acquired hemophilia successfully treated with oral immunosuppressive therapy.

CASE

A 40-year-old woman was referred to our outpatient clinic for the evaluation of bleeding tendencies for 6 months. Four months previously, she had visited a local hospital because of gross hematuria, but an urologic examination by cystoscopy showed no abnormal findings. She had two vaginal deliveries without any bleeding episodes in the past. There was no history of illicit drug use or alcohol intake. There was no family history of abnormal bleeding.

Laboratory investigations revealed normal blood counts, liver function tests, renal function studies and urinalysis. Coagulation profiles were PT 12.9 sec (control 12.5 sec), aPTT 75.7 sec (control from 28 to 40 sec), BT 2 min, and fibrinogen assay 185 mg/dL. Factor VIII level was 1.5%, Factor IX was 34%, von Willebrand factor antigen was 137.2% and ristocetin cofactor level 85.4%. The aPTT was not corrected completely when mixed with normal plasma. Antinuclear antibodies, anti-Sm antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies, antic-ardiolipin antibodies, lupus anticoagulant and anti-β2-glycoprotein I IgG were all negative. A titer of Factor VIII inhibitor was 27.50 Bethesda units (BU)/mL (normal < 0.01 BU/mL).

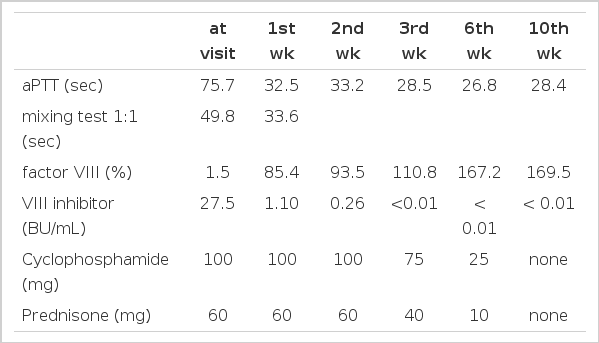

Two weeks later, she was admitted to our hospital for severe right shoulder pain and swelling. She received cyclophosphamide 100 mg p.o once daily and prednisone 60 mg p.o daily in three divided doses. In addition, pain control with intravenous morphine was initiated. On the fourth day, she showed a significant relief of the shoulder pain with normal level of aPTT and was discharged. After one week, the aPTT was 38.2 sec and the factor VIII inhibitor level was decreased to 1.10 BU/mL. At the 3rd week, the dose of cyclophosphamide and prednisone were slowly tapered because the factor VIII inhibitor titer dropped below 0.001 BU/mL. On the 7th week, her medication was stopped. Her clinical course is described in Table 1. She is currently being followed monthly and is in remission.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous development of autoantibodies against FVIII:C in a nonhemophilic infrequently occurs with an incidence of 0.2–1 case per 1 million persons per year, and is associated with a varying mortality between 15 and 22%1,5). Acquired hemophilia usually occurs with no identifiable causes, particularly in the population older than 60 years of age. It has been also reported in association with various autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, inflammatory bowel disease, postpartum women, hematologic malignancies, solid tumors and certain medications, such as penicillin, sulfonamides, chloramphenicol and phenytoin6).

These autoantibodies are composed predominantly of immunoglobulin G (IgG). Although the pathogenesis of acquired hemophilia is still unexplained, the interaction chiefly between the IgG and distinct epitopic sites on the FVIII:C molecule can be speculated7).

The hemorrhagic manifestations of acquired hemophilia present with a wide range of clinical severity, including gastrointestinal bleeding, hemorrhages into muscle and joints, syncope, ecchymosis, hematuria, or sustained bleeding after surgery or minor trauma8). The diagnosis of acquired hemophilia is based on clinical and laboratory findings which are prolonged aPTT with normal PT, factor VIII deficiency, unresponsiveness to factor VIII infusion and the elevated level of factor VIII inhibitors.

Asymptomatic patients with low titers of factor VIII inhibitor may be closely monitored without treatment because of spontaneous recovery. Patients with high titers of inhibitor or hemorrhage usually require immediate control of the hemorrhage followed by aggressive immunosuppression to prevent severe illness or death. However, the optimal management of acquired hemophilia is controversial and there are no randomized trials, although various modalities, such as immunosuppression, administration of prothrombin complex concentrates, recombinant factor VIIa or intravenous IgG, or plasmapheresis, have been suggested8,9).

Recently, low-dose oral cyclophosphamide and prednisone without factor VIII infusion have emerged as an attractive method of immunosuppression achieving complete remission of all the treated patients3,4). The most striking difference of this study from previous ones10,11) is the continued administration of immunosuppressive agents at full dose until complete remission is achieved, tapered gradually while the patient is observed for a return of the antibody titer. Our patient was presented with gross hematuria and right shoulder bleeding, and received the above regimen achieving a complete remission at 3 weeks. Our results were similar to previous reports3,4).

In summary, we had a case of acquired hemophilia successfully treated with daily low-dose oral cyclophosphamide and prednisone. Further randomized studies on more patients are needed to confirm whether oral immunosuppressive regimen, including cyclophosphamide and prednisone, is a main therapeutic approach.