Autoimmune Hepatitis in a Patient with Myasthenia Gravis and Thymoma – a Report on the First Case in Korea

Article information

Abstract

Myasthenia gravis is an autoimmune disease that results from an antibody-mediated reaction and occurs with thymoma in 15% of patients. It is very rarely associated with autoimmune hepatitis. Four cases of myasthenia gravis with autoimmune hepatitis have been reported in the world, We recently experienced a case of 30-year-old man with myasthenia gravis associated with thymoma and autoimmune hepatitis. This condition is the first case that has not been reported previously in Korea. We report this rare condition along with a brief review of the literature.

INTRODUCTION

Myasthenia gravis is known to occur with thymoma in 10–15% of patients and with other autoimmune diseases, such as hyperthyroidism, polymyositis and systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and ulcerative colitis1). Nevertheless, autoimmune hepatitis is known to be very rarely associated2). Four cases of myasthenia gravis associated with autoimmune hepatitis have been reported in the world2–5). We recently experienced a case of 30-year-old man with myasthenia gravis with thymoma and autoimmune hepatitis. To the best of our knowledge, myasthenia gravis with thymoma and autoimmune hepatitis has not been reported previously in Korea.

CASE

A 30-year-old male patient was admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine at our hospital for the evaluation and treatment of ptosis of the right eye and blurred vision for 1 month. The patient also experienced fatigue and generalized weakness. He was neither a smoker nor an alcoholic, and had no history of drug abuse, including herbs. His family history was unremarkable. On physical examination, his height was 173 cm, body weight was 63 kg. Body temperature was 36.5°C, pulse rate was 20/min, respiratory rate was 20/min and blood pressure was 120/70 mmHg. He had a chronically ill appearance and the sclera was not icteric. On respiratory and cardiac auscultation, no abnormal sound heard. On abdominal examination, abnormal tenderness and hepatosplenomegaly were not detected. On neurologic examination, the function of the cranial nerves, including pupillary reflexes of both eyes, was intact and the pathologic reflexes, including the Babinski sign, were not detected. A pathognomonic sign of myasthenia gravis, tensilon test, was positive. Hematologic tests showed WBC 3900/mm3, hemoglobin 13.4 g/dL, platelet 139,000/mm3, and blood chemistry showed total bilirubin 1.4 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase 82 U/L, total protein/albumin 7.3/5.0 g/dL, gamma GT 32 U/L, BUN/creatinine 10/0.9 mg/dL, LDH 371 U/L, CK 57 U/L, Na/K/Cl 145/4.1/106 mmole/L. However, liver enzymes were markedly elevated (AST/ALT 400/777 U/L) and prothrombine time was slightly prolongated (INR 1.35). Anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody titer was elevated to 3.8 nmole/L (normal < 0.2 nmole/L). Tests of etiologic agents for viral hepatitis were anti-HAV IgM (−), HbsAg (−), anti-HBs (−), HBV-DNA (−), anti-HCV (−), HCV-RNA by PCR method (−), anti-HDV by RIA method (−), HEV (−), anit-CMV IgM (−), and anti-EBV (−). Autoantibody were ANA (+, 1:40, speckled pattern), anti-smooth muscle Ab (−), anti-LKM Ab (−), anti-microsomal Ab (−), anti-mitochodrial Ab (−), anti-dsDNA Ab (−), anti-smooth Ab (−), anti-thyroglobulin Ab (−). Screening tests for Wilson’s disease showed normal values, serum copper 99 g/dL and serum ceruloplasmin 20 mg/dL, and Kayser-Fleisher rings were not observed. Alpha1-antitrypsin was 244 mg/dL and serum choline esterase was 1605 IU/L. These were within normal value. Thyroid fuction tests showed T3 153 ng/dL, T4 11.1 g/dL, TSH 2.33 IU/mL. The urinalysis was normal. A chest X-ray showed no active parenchymal lung lesion or mass, but the chest CT scan showed 3×4×5 cm-sized low-attenuated homogenous oval shaped mass with sharp margin at the anterior mediastinum. There was no enlargement of lymph node in thoracic cavity. The mass was diagnosed as thymoma, radiologically (Figure 1). Abdominal sonography showed no abnormal findings. His HLA typing was A11, A31, B51, B13, Cw4, Cw6, DR09 and DR12. In the follow-up liver function tests, AST/ALT were elevated to 331/918 and liver biopsy was performed. Biopsy showed distorted lobular architecture and widening of portal tracts by chronic inflammatory cell infiltration with foci of piecemeal necrosis and fibrosis. Thus it was diagnosed as chronic active hepatitis (Figure 2). According to the scoring system of International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group, his pretreatment score was 14, which is compatible with the probable diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. He was treated with prednisone 30 mg/day per oral and 20 days later AST/ALT decreased to 45/73 IU/L and, thereafter, he received thymectomy. On operative fields, solid mass (3×4×5 cm) was identified at the anterior mediastinum. It was encapsulated with yellow gelatin-like material. Histology confirmed that the thymoma was encapsulated, non-invasive and mixed type (Figure 3). After thymectomy, ptosis and blurred vision disappeared. Prednisone was gradually tapered and stopped, but AST/ALT level was elevated up to 239/393 U/L. Therefore, he was treated again with prednisone, 10 mg/day, and liver function returned to normal value. His post-treatment score was 17, which is compatible with the definite diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis.

Chest CT scan. It shows 3×4×5 cm-sized low-attenuated homogenous oval shaped mass with sharp margin at the anterior mediastinum. It is diagnosed as thymoma radiologically.

Histopathology of the liver. It shows distorted lobular architecture and widening of portal tracts by chronic inflammatory cell infiltration with foci of piecemeal necrosis and fibrosis (H&E, ×200).

DISCUSSION

Myasthenia gravis is an organ-specific autoimmune disease that results from an antibody-mediated assault on the muscle nicotinic acetylcholine receptor at the neuromuscular junction6). Thymomas are found in approximately 15% of myasthenia gravis patients and are usually associated with a later age of disease onset. Thymectomy increases the remission rate and improves the clinical course of myasthenia gravis.

About 10% of myasthenia gravis patients are associated with another autoimmune diseases, such as hyperthyroidism, polymyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, sarcoidosis, pernicious anemia, but autoimmune hepatitis is very rarely associated1).

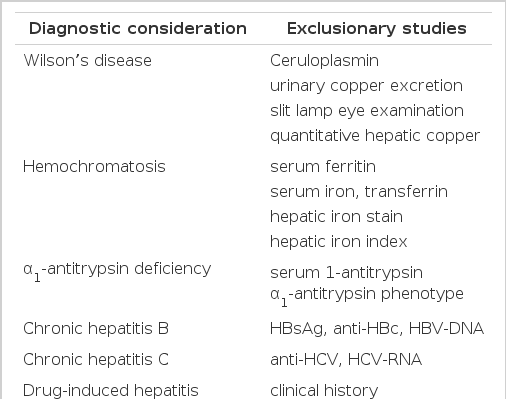

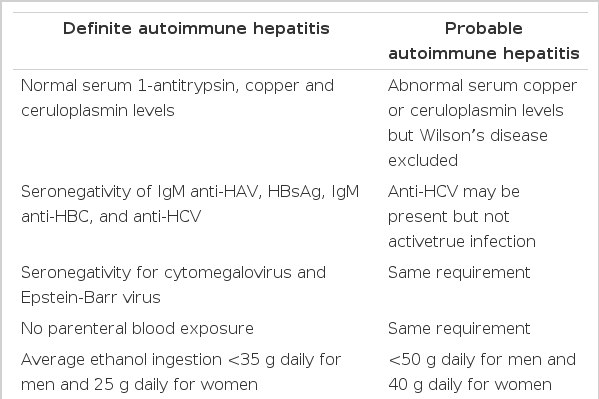

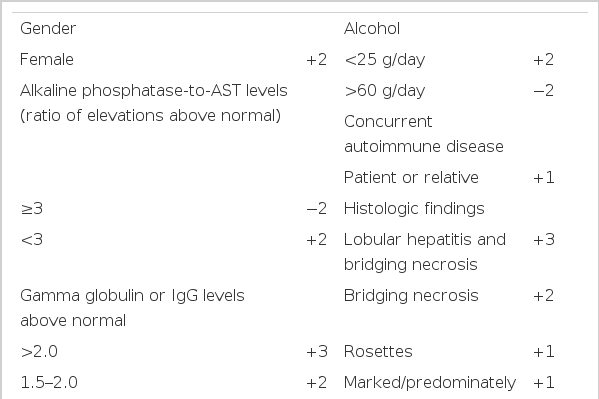

There is no individual feature that is pathognomonic for autoimmune hepatitis, and its diagnosis requires the confident exclusion of other conditions because the clinical course, treatments and prognosis is different (Table 1)7). For example, genetic disorders of the liver, including Wilson’s disease, hemochromatosis and alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency must be confidently excluded because of different effective therapies or important familial implications. Drug-induced liver disease, especially those associated with the use of alpha-methyldopa, nitrofurantoin and propylthiouracil, must be excluded because discontinuation of the drug cures the disease. Chronic viral infection, especially those related to the hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus, must be excluded because antiviral therapy in selected instances may be beneficial. The International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAHG), the Working Party of the World Congress of Gastroenterology (WCC) and the International Association for the Study of the Liver (IASL) proposed the clinical criteria for the definite and probable diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis(Table 2)8). They emphasize the importance of compatible findings in laboratory profiles and liver histology and the absence of other etiologic factors. Our patient is compatible with definite autoimmune hepatitis by clinical criteria. The IAHG has also proposed a scoring system for the definite and probable diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis (Table 3)8). It has the theoretic advantages of including all features of the disease in the final diagnosis, balancing diagnostically compatible and incompatible findings in an objective fashion7). Our patient had the corticosteroid- pretreatment aggregate scores of 14, thus the probable diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis was possible, and it increased up to 17 after treatment with steroid, which was compatible with the definite diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis.

Clinical criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group

Quantitative criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis adapted from the recommendations of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group

Seronegativity for anti-smooth muscle Ab and anti-nuclear Ab no longer precludes the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis8). The strength of the clinical, laboratory and histologic findings can support the diagnosis even if the unconventional immunoassasys are unavailable or negative (see Table 2)8–10).

A conceptual framework for the pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis is that a genetically predisposed host is exposed to an environmental agent which triggers an autoimmune process directed at liver antigens, causing a progressive necroinflammatory reaction that results in fibrosis and cirrhosis. As in other autoimmune diseases, there are primary associations with the HLA B8, DR3 and DR52a loci. There is also a secondary association with HLA-DR4 in white patients and a primary association with HLA-DR4 in Asians9). However, no related HLA locus was detected in our patient. Nowadays, the disease association with specific loci in the HLA-DR region and identified specific amino acid sequences in the light chains of the HLA-DR beta molecules were suggested as more specific markers11). The susceptibility of the patient to myasthenia gravis and autoimmune hepatitis seems to be related to HLA DR3. There is probably an inter-play of genetic and environmental factors in the occurrence of these diseases2).

Autoimmune hepatitis generally is responsive to corticosteroid treatment and the remission rate induced by initial therapy is approximately 80%. In general, the pro-gnosis is inversely correlated with the histologic severity of the disease9). The course of myasthenia gravis is variable. Exacerbations and remissions may occur, but remissions are rarely complete or permanent. Virtually all myasthenic patients can achieve full productive lives with proper therapy, such as anticholinesterases, prednisone, azathioprine and plasmapheresis12). Prednisone treatment induces remission or significantly improves the disease in more than half of the patients1). Despite the coexistence of the autoimmune hepatitis and myasthenia gravis, a good response can be obtained with prednisone and thymectomy.