Early versus late bedside endoscopy for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a life-threatening complication in critically ill patients. The aim of this study was to determine the efficacy of bedside endoscopy in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting, and to compare the outcomes of early endoscopy (within 24 hours of detecting GI bleeding) with late endoscopy (after 24 hours).

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients who underwent bedside endoscopy for nonvariceal upper GI bleeding and lower GI bleeding that occurred after ICU admission at Seoul National University Hospital from January 2010 to May 2015.

Results

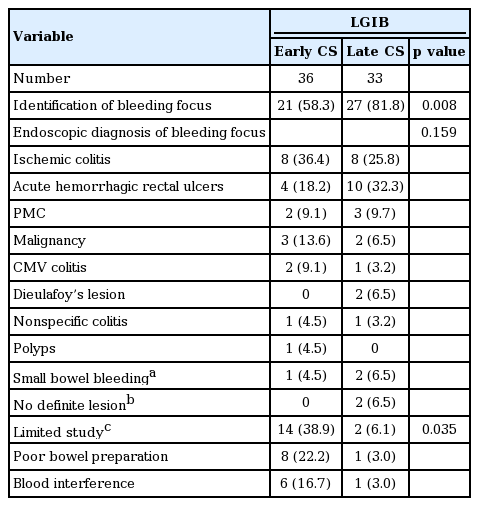

Two hundred and fifty-three patients underwent bedside esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for upper GI bleeding (early, 187; late, 66) and 69 underwent bedside colonoscopy (CS) for lower GI bleeding (early, 36; late, 33). Common endoscopic findings were peptic ulcer, and acute gastric mucosal lesion in the EGD group, as well as ischemic colitis and acute hemorrhagic rectal ulcers in the CS group. Early EGD significantly increased the rate of finding the bleeding focus (82% vs. 73%, p = 0.003) and endoscopic hemostasis (32% vs. 12%, p = 0.002) compared with late EGD. However, early CS significantly decreased the rate of identifying the bleeding focus (58% vs. 82%, p = 0.008) and hemostasis (19% vs. 49%, p = 0.011) compared with late CS due to its higher rate of poor bowel preparation and blood interference (38.9% vs. 6.1%, p = 0.035).

Conclusions

Early EGD may be effective for diagnosis and hemostatic treatment in ICU patients with GI bleeding. However, early CS should be carefully performed after adequate bowel preparation.

INTRODUCTION

Critically ill patients often develop upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB). Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a significant complication that causes increased morbidity and mortality in those patients. Furthermore, managing GI bleeding in intensive care unit (ICU) patients remains difficult because most patients have multiple and complex poor prognostic features and transfer to the endoscopy room for endoscopy is not possible in most cases. In this situation, bedside endoscopy was performed in the ICU. The endoscopy that was performed within 24 hours of the detection of bleeding was considered early endoscopy. However, the efficacy and role of early bedside endoscopy in ICU patients is still controversial.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) has been reported to be an effective strategy for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with UGIB [1,2]. In particular, early EGD (within 24 hours of GI bleeding onset) has been shown to improve clinical outcomes [1]. Colonoscopy (CS) also has been shown to be valuable in diagnosing and managing LGIB patients in a non-ICU setting [3]. However, urgent CS did not reduce the transfusion requirements, rebleeding rate, or mortality in a randomized controlled study [4].

In an ICU setting, few studies have reported the efficacy of early bedside endoscopy compared to late endoscopy for GI bleeding. Furthermore, there was a controversy in the usefulness of early CS in ICU patients with LGIB [5,6]. Therefore, we conducted this retrospective study to determine the clinical characteristics of GI bleeding and the efficacy of bedside endoscopy for GI bleeding that developed during an ICU stay. We also compare the outcomes of early endoscopy with late endoscopy.

METHODS

Study design and ethical consideration

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients undergoing bedside endoscopy for nonvariceal UGIB and LGIB that developed during an ICU stay at Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH), a tertiary referral center in Korea, from January 2010 to May 2015. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee at SNUH (IRB No. 1512-044-727).

Bedside endoscopy and bowel preparation

In this study, GI bleeding was diagnosed when overt bleeding, such as hematemesis, bloody nasogastric drainage, melena or hematochezia occurred. All endoscopies were performed at bedside in the ICU when GI bleeding was diagnosed and suspected. Early endoscopy was defined as endoscopy performed within 24 hours of detecting GI bleeding and was initially considered in the patients with GI bleeding in our hospital. When GI bleeding presented during the work day or weekdays, early endoscopy was generally performed in most cases. However, when GI bleeding occurred during off-hours or weekends, we were more likely to perform late endoscopy. If a patient experienced multiple endoscopies, only the initial endoscopy for GI bleeding was analyzed. A 103-cm esophagogastroduodenoscope (EVIS Lucera GIF H260, Olymphus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) and 133-cm colonoscope (EVIS Lucera CF H260AL/I, Olympus Optical) were used. Generally, bowel preparation consisted of 4 L of oral polyethylene glycol solution. The use of nasogastric tubes to prepare a patient for CS may be required in patients unable to drink fluids.

Study population and variables

Patient characteristics, including age, sex, diagnosis at admission, length of stay in the ICU, the need for mechanical ventilation (MV), the duration of MV, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, mental status based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), presence of multiple organ dysfunction, presence of shock (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg and peripheral circulatory failure), in-hospital medical therapy (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antiplatelets, anticoagulants, or corticosteroids), stress ulcer prophylaxis (histamine 2 receptor antagonists, proton-pump inhibitors, or sucralfate), enteral nutrition, anemia, coagulopathy, and other laboratory data such as blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine (Cr), and liver function (aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase) were collected when GI bleeding occurred. Coagulopathy was defined as a platelet count < 50,000/mm3 or an international normalized ratio > 1.5.

Clinical outcome variables included the experience of the endoscopist (expert or fellow), rate of identification of bleeding focus, primary hemostasis rate, mode of endoscopic hemostasis, rates of second endoscopy, angiography, surgery, units of red blood cell (RBC) transfused, length of hospitalization, length of ICU stay, recurrent bleeding rate, in-hospital mortality, and cause of death. Endoscopic hemostasis therapy included the use of argon plasma coagulation, ligation, hemoclipping, therapy with epinephrine (injection or spray), and heater probe therapy. Although a single endoscopic therapy was used in most cases in this study, in cases in which two or more hemostatic therapies for GI bleeding were used, the typical intervention was regarded as the appropriate endoscopic hemostasis for specific lesions listed in a previous study [7]. Recurrent bleeding was defined as hematemesis or hematochezia, bloody nasogastric drainage, instability of vital signs and a greater than 2 g/dL reduction in hemoglobin level within 24 hours after successful primary hemostasis [6].

Endoscopic outcomes included endoscopic diagnosis of the bleeding focus, type of bleeding stigmata, and reasons for limited study. Endoscopic diagnosis of UGIB included an ulcer with profusely bleeding stigma, an ulcer with clean base or firmly adherent blood clot, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, Dieulafoy’s lesion, angiodysplasia, esophagitis, acute gastric mucosal lesion (AGML), and malignancy. The type of bleeding stigmata in UGIB included a spurting artery (Forrest Ia), an oozing vessel (Forrest Ib), and a visible non-bleeding vessel (Forrest IIa). The endoscopic diagnosis of LGIB included ischemic colitis, acute hemorrhagic rectal ulcers, pseudomembranous colitis, malignancy, cytomegalovirus colitis, Dieulafoy’s lesion, nonspecific colitis, and polyps. Reasons for limited studies in CS included poor bowel preparation, blood interference and small bowel bleeding. Poor bowel preparation was defined as an Aronchick scale of more than 4 (poor, inadequate) [8], and small bowel bleeding was suspected when fresh blood was still noted at the terminal ileum or blood was passed through the ileocecal valve.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were calculated as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as the number (%). Student t test was used to compare continuous variables, and chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables between the two groups. Furthermore, the impact of early endoscopy on the clinical outcomes of patients with GI bleeding and the risk factors for recurrent GI bleeding were evaluated using multiple logistic regression analysis. The relative risk and 95% confidence interval of the significant factors were calculated. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients with GI bleeding that developed during an ICU stay

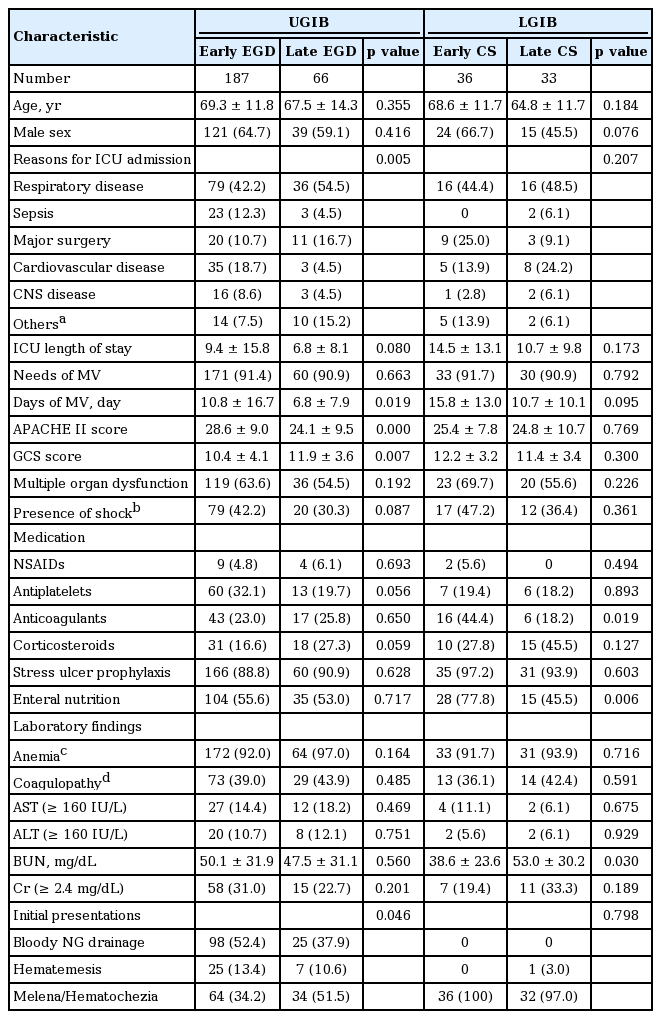

A total of 314 ICU patients underwent bedside endoscopy for nonvariceal GI bleeding that developed after the ICU admission at SNUH from January 1, 2010 to May 31, 2015. Of these, 253 patients underwent bedside EGD and were enrolled in the UGIB group. The other 69 patients underwent bedside CS and were enrolled in the LGIB group. Early endoscopy was performed in 187 patients (73.9%) with UGIB and 36 patients (52.2%) with LGIB. Comparisons of baseline characteristics in patients who did and did not undergo early endoscopy are described in Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of early and late endoscopy in patients who received bedside endoscopy for gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU

In the UGIB group, baseline characteristics of the early EGD group and the late EGD group were not significantly different in age, gender, length of ICU stay, need for MV, multiple organ dysfunction, presence of shock, medication, or laboratory findings. The most common reason for admission to the ICU was respiratory disease (early 42.2%, late 54.5%) in both groups. Bloody nasogastric tube drainage was the most common reason for early EGD (52.4%), and melena/hematochezia was the most common reason for late EGD (51.5%). However, bloody nasogastric drainage was found only in 48.6% (123/253) of patients in the UGIB group. The patients who underwent early EGD had a higher APACHE II score and a lower GCS score compared with the patients who underwent late EGD.

In the LGIB group, baseline characteristics of the early CS group and late CS group were not significantly different in age, gender, reason for ICU admission, length of ICU stay, APACHE II score, GCS score, use of MV, multiple organ dysfunction, presence of shock, medication, and laboratory findings. The most common reason for CS was hematochezia/melena in both groups (100% vs. 97.0%). The patients in the early CS group were treated more often with anticoagulants (44.4% vs. 18.2%, p = 0.019). The patients in the who underwent early CS had a lower BUN level compared with the patient who underwent late CS (38.6 ± 23.6 vs. 53.0 ± 30.2, p = 0.030)

Clinical outcomes of early or late bedside endoscopy in the ICU

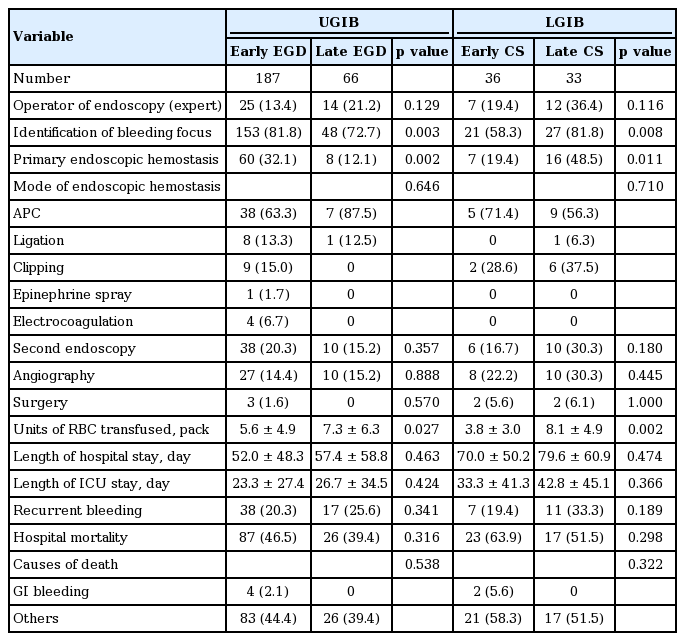

Early endoscopy was performed in 187 patients (73.9%) with UGIB and 36 patients (52.2%) with LGIB. Comparisons of outcomes between early and late endoscopy are listed in Table 2. There were no significant differences in length of hospital or ICU stay, rate of recurrent bleeding, or mortality rate between early endoscopy and late endoscopy in both UGIB and LGIB.

Clinical outcomes of early and late endoscopy in patients who received bedside endoscopy for GI bleeding in the ICU

Early EGD in the UGIB group was significantly associated with higher rates of bleeding site identification (81.8% vs. 72.7%, p = 0.003) and endoscopic hemostasis (32.1% vs. 12.1%, p = 0.002) as well as fewer units of transfused RBCs (5.6 ± 4.9 packs vs. 7.3 ± 6.3 packs, p = 0.027). In total, 68 patients (26.9%) with UGIB underwent primary endoscopic hemostasis. However, recurrent GI bleeding occurred in 55 patients (21.7%) and a second endoscopy was performed in 48 patients (19%) to re-identify the source of bleeding or provide hemostasis. Thirty-seven patients (14.6%) received angiography, and three (1.2%) underwent surgery. The in-hospital mortality rate was 44.7%, but UGIB-related death occurred in only four patients (1.6%).

Early CS in the LGIB group was significantly related to lower identification of bleeding focus (58.3% vs. 81.8%, p = 0.008) and endoscopic hemostasis rates (19.4% vs. 48.5%, p = 0.011). However, early CS in the LGIB group decreased RBC transfusion (3.8 ± 3.0 packs vs. 8.1 ± 4.9 packs, p = 0.002). In total, the endoscopic hemostasis rate (33.3%) and recurrent bleeding rate (26.1%) in LGIB were similar to those in UGIB. In-hospital mortality was 58%, but only two (5%) experienced in-hospital mortality related to LGIB, and there were no complications related to CS.

Endoscopic findings of bedside endoscopy in the ICU

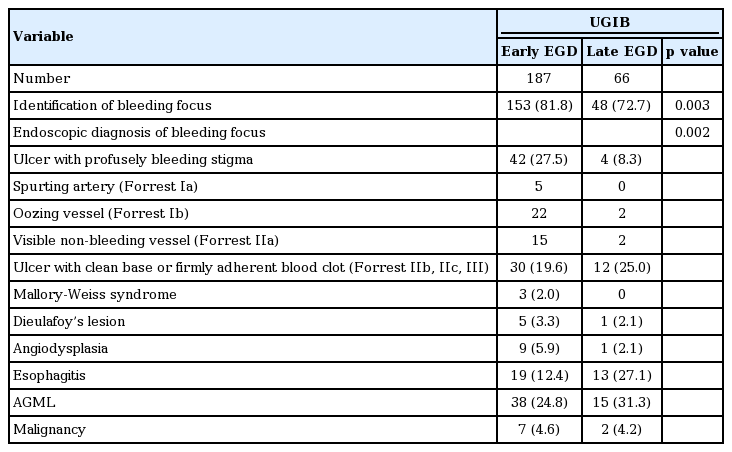

The endoscopic findings are shown in Tables 3 and 4. In UGIB, peptic ulcer was the most common bleeding source among identified bleeding source in both early and late EGD group (47.1% vs. 33.3%, p = 0.037). The others were AGML (24.8% vs. 31.3%) and esophagitis (12.4% vs. 27.1%) in both the early and late EGD group. In LGIB, common endoscopic diagnoses included ischemic colitis (36.4% vs. 25.8%), acute hemorrhagic rectal ulcers (18.2% vs. 32.3%), pseudomembranous colitis (9.1% vs. 9.7%), and malignancy (13.6% vs. 6.5%). In the early CS group, poor bowel preparation and blood interference of observation were significantly more frequent than in the late CS group (38.9% vs. 6.1%, p = 0.035). In total, CS failed to identify the bleeding site due to poor bowel preparation (13.0%) or blood interference (10.1%). In one patient (2.8%) in the early CS group and two patients (6.1%) in the late CS group, bleeding was thought to originate from the small bowel. Finally, among 314 patients with GI bleeding, 15 (4.8%) were diagnosed with small bowel bleeding by CT angiography, angiography and surgery.

Endoscopic findings of early and late endoscopy in patients who received bedside endoscopy for gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU: endoscopic findings of bedside EGD in the ICU

DISCUSSION

We investigated the clinical characteristics of GI bleeding that occurred in the ICU and the efficacy of bedside endoscopy, especially the comparison of the outcomes of early endoscopy with late endoscopy. Common causes of UGIB in ICU patients, in the present study, were peptic ulcer and AGML. This is consistent with results from previous studies [5,9]. Furthermore, peptic ulcers and erosive diseases accounted for nearly 50% and 20% to 35% of UGIB in general patients admitted to the hospital for bleeding [9,10]. Taken together, the source of UGIB was not significantly different between ICU patients and patients admitted to the hospital for UGIB. In contrast, the typical causes of LGIB in the general population are angiodysplasia, diverticular disease, polyps, and malignancy, accounting for more than 50% of cases of LGIB [11]. In this study, the cause of LGIB in ICU patients was distinct and included ischemic colitis, acute hemorrhagic rectal ulcer, and pseudomembranous colitis. Those findings were supported by a previous study [12]. These differences could be related to comorbid illnesses, old age, hemodynamic instability, or prolonged use of antibiotics in ICU patients.

We demonstrated that the diagnostic rate of endoscopy was 79.4% (201/254) for UGIB and 69.4% (48/69) for LGIB. Endoscopy can identify the bleeding site in more than 95% of cases of UGIB and 74% to 90% of LGIB cases in the general population [2,13-15]. However, in ICU patients with GI bleeding, the diagnostic rates of bedside endoscopy for UGIB and LGIB were 85% and 65% to 67%, respectively [6,12,16]. This result confirms that the diagnostic yield of endoscopy is lower among ICU patients than in the general population.

Our study reported lower endoscopic hemostasis rates, 26.9% (68/254) for UGIB and 33.3% (23/69) for LGIB. Several studies of UGIB in the general population reported rates of endoscopic hemostasis for peptic ulcer disease above 90% [17-19], and the primary endoscopic hemostasis rate was 62% in LGIB [3,10]. Our findings suggested either a lower therapeutic role of endoscopy or a decreased need for hemostasis in ICU patients.

Early EGD, in the present study, was associated with an increased diagnostic rate and primary hemostasis rate. However, early EGD in UGIB did not decrease mortality or rebleeding rates compared with late EGD in this study. In general, early EGD has been shown to decrease the morbidity, mortality, and rebleeding rate in both non-ICU and ICU settings [20]. Chak et al. [7] reported that early EGD was associated with a 20% reduction in the length of ICU stay and a 33% reduction in the length of hospital stay. These differences in our study could be related to the higher APACHE II score observed in the early EGD group compared to the late EGD group. This could be why we performed early endoscopy in more ill and unstable patients. Early CS, in the present study, was related to a reduced diagnostic rate and primary hemostasis rate. This could be explained by the higher rate of poor bowel preparation and blood interference observed in the early CS group compared to the late CS group (38.9% vs. 6.1%, p = 0.035). Thus, early EGD could be considered in ICU patients with GI bleeding, but CS would be conducted after careful bowel preparation.

Patients with GI bleeding exhibit significantly higher mortality than patients without GI bleeding [21]. Our observed in-hospital mortality rates of 44.7% (113/253) in UGIB and 58% (40/69) in LGIB are comparable to the reported mortality rates of ICU patients who underwent endoscopy for GI bleeding (48.5% to 77.1%) [6,22]. Furthermore, these rates were significantly higher than the mean in-hospital morality rate of 30% for the ICU patients in SNUH during the same period. GI bleeding-related mortality rates in our study were low at 1.6% of UGIB and 2.9% of LGIB, similar to rates ranging from 0% to 6.2% in previous studies [5,6]. This finding suggests that it is important to control for underlying diseases in ICU patients with GI bleeding because critically ill patients with GI bleeding usually die from decompensation of underlying diseases rather than bleeding.

This study has some limitations. Since this study was retrospective in design, we could not control all confounding factors in the analysis. Many confounding factors such as a different indication or timing for early endoscopy according to doctors might affect the results. Furthermore, a higher APACHE II score in early EGD, compared to late EGD, might influence the outcomes such as mortality rate and length of hospital or ICU stay. However, this is the first study to compare the outcome of early and late bedside endoscopy for both UGIB and LGIB that developed in the ICU patients.

In conclusion, critically ill patients with UGIB that occurred while in the ICU stay had similar sources of bleeding as patients admitted to the hospital with bleeding. However, ICU patients with LGIB exhibited distinct sources of bleeding. Although bedside endoscopy showed an acceptable diagnostic rate without procedure-related complications, rates of endoscopic diagnosis and hemostasis in ICU patients were lower than those in the general population. Early bedside EGD was effective for diagnosis and treatment in ICU patients with GI bleeding. However, early CS decreased diagnostic and hemostatic rates because of its higher rate of poor bowel preparation and blood interference compared with late CS. Thus early CS should be performed after adequate bowel preparation.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Early bedside esophagogastroduodenoscopy for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding was effective for diagnosis and hemostatic treatment in intensive care unit (ICU) patients.

2. The effectiveness of early bedside colonoscopy in ICU patients was limited because of its higher rate of poor bowel preparation and blood interference compared with late colonoscopy. Thus early colonoscopy should be performed after adequate bowel preparation.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.