Pre-discharge anemia as a predictor of adverse clinical outcomes in patients with acute decompensated heart failure

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

The impact of the timing of anemia during hospitalization on future clinical outcomes after surviving discharge from an index heart failure (HF) has been poorly studied in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF).

Methods

A total of 384 surviving patients with acute ADHF were divided into two groups: an anemia group (n = 270, 199 anemia at admission and 71 pre-discharge anemia) and a no anemia group (n = 114). All-cause mortality and HF re-hospitalization were compared between groups.

Results

During the follow-up period (median, 528 days), death occurred in 60 patients (15.6%) and HF re-hospitalization occurred in 131 patients (34.1%). Overall anemia was associated with increased mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03 to 3.01; p = 0.039), but not HF re-hospitalization (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.42; p = 0.707). Pre-discharge anemia was significantly associated with increased mortality (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.82; p = 0.048), but anemia at admission did not predict increased mortality or re-hospitalization.

Conclusions

Pre-discharge anemia, rather than anemia at admission, was identified as an independent predictor of mortality in patients with ADHF after surviving discharge. The results of the present study suggest that the identification and optimal management of anemia during hospitalization are important in patients with ADHF.

INTRODUCTION

Anemia, defined as a decreased level of blood hemoglobin (Hgb), is common in patients with heart failure (HF). Previous studies have demonstrated that anemia is not only an important predisposing condition of HF aggravation, but also a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) [1-4].

Despite the importance of anemia in ADHF, previous studies have mostly focused on the clinical significance of anemia at admission. Few studies have investigated the associations between clinical outcomes and anemia developing at different times during hospitalization, even though anemia can onset at any time during hospitalization in association with blood loss, infection, impaired renal function, or other causes [5]. Recent studies have suggested that dynamic changes of Hgb levels are associated with future clinical outcomes in patients with ADHF [6-8].

We hypothesized that pre-discharge anemia may not be managed appropriately following discharge after HF, even though anemia at admission is usually corrected during hospitalization in patients with ADHF. Therefore, there is a possibility that pre-discharge anemia, as compared to anemia at admission, may have a more significant impact on future clinical outcomes in ADHF. Consequently, we evaluated the impact of anemia that developed at any time during hospitalization on future clinical outcomes after discharge in patients with ADHF.

METHODS

Study design and population

The present study used a single-center, retrospective observational design, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (approval number: CNUH-2015-231) of our institution. A waiver for informed consent was obtained from the Institutional Review Board.

From May 2011 to March 2013, a total of 394 consecutive patients with ADHF were identified. After excluding 10 patients who died during hospitalization, 384 surviving patients were enrolled in the present study and divided into two groups according to the presence of anemia during hospitalization: an anemia group (presence of anemia at any time during hospitalization; n = 270, 71.3 ± 11.8 years, 131 males) and a no anemia group (n = 114, 62.4 ± 16.4 years, 62 males). All patients were treated with transfusion to raise the level of Hgb above 7 g/dL during hospitalization.

All-cause mortality and HF-related re-hospitalization during clinical follow-up were compared between groups. Two separate additional analyses were performed to investigate the impact of anemia at different times during hospitalization: admission anemia versus no admission anemia, and discharge anemia versus no discharge anemia.

Study definitions

ADHF was diagnosed by the combination of typical symptoms and/or signs, echocardiographic findings, and elevated levels of natriuretic peptides according to the current guidelines for HF [9-11]. The severity of ADHF was evaluated using New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification at the time of admission and discharge in all patients.

Serial levels of Hgb were checked during hospitalization, and anemia was defined according to the World Health Organization definition (Hgb < 13 g/dL in men and < 12 g/dL in women) [12]. Admission and discharge anemia were diagnosed using the first Hgb value obtained during hospitalization and the last Hgb value before discharge, respectively. We also defined hospital-acquired anemia, which included discharge anemia, using the lowest Hgb value in patients without admission anemia.

Echocardiography examination

Echocardiography examinations were performed using a digital ultrasonography system (Vivid 7, GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horten, Norway), and all data were analyzed using a computerized software package (EchoPAC PC 6.0.0, GE Vingmed Ultrasound). The protocol of our echocardiography laboratory was summarized previously [13]. Comprehensive echocardiographic studies, including Doppler studies, were performed as soon as possible after hospitalization according to the current guideline [14]. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured using Simpson’s method, and intra- and interobserver variation for LVEF were 4% ± 5% and 5% ± 4%, respectively (absolute difference divided by the mean of the measured value).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or as medians and interquartile ranges, and were compared using the unpaired t test or the Mann-Whitney rank-sum test. Discrete variables are expressed as counts and percentages, and were analyzed with Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test. We constructed Kaplan-Meier curves to compare the study endpoints between the two groups, and differences were assessed with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression with adjustment for covariates was used to assess clinical outcomes. Variables with p < 0.05 in univariate Cox regression analysis, and those known to be relevant to clinical outcomes in ADHF were included in the multivariate Cox regression analysis: age, systolic blood pressure ≤ 100 mmHg, NYHA classification, diabetes mellitus, ischemic etiology of ADHF, LVEF, atrial fibrillation, hyponatremia, and serum creatinine. All analyses were two-tailed, and all variables were considered significant at a value of p < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows software version 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Anemia was identified in 270 patients during hospitalization; anemia at admission in 199 patients (70.3%); and pre-discharge anemia in 71 patients (29.7%).

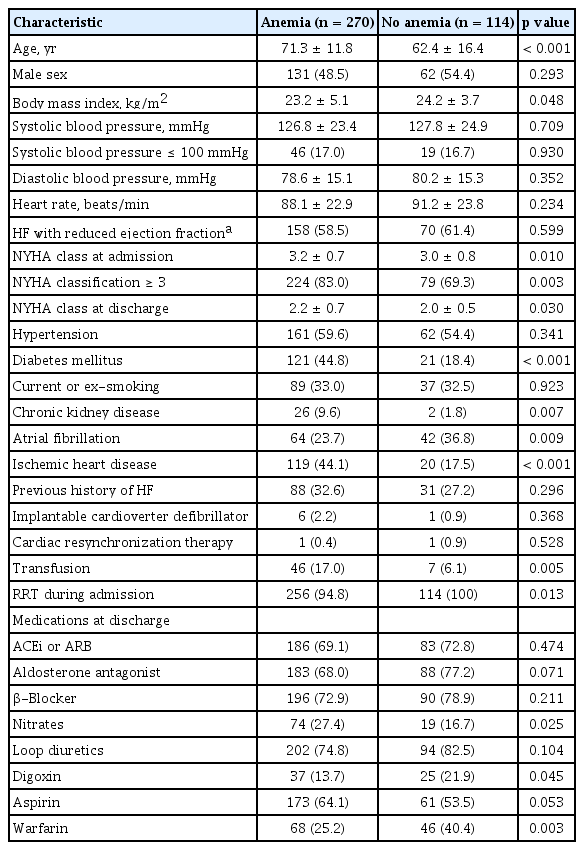

Baseline clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The age and body mass index of the anemia group were higher and lower, respectively, compared to those of the no anemia group. The prevalence of HF with reduced ejection fraction was similar between groups. Diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, and ischemic heart disease were significantly prevalent in the anemia group, whereas atrial fibrillation was significantly prevalent in the no anemia group. The degree of dyspnea, as measured by NYHA class, was significantly greater in the anemia group than in the no anemia group. Nitrates were more commonly prescribed in the anemia group, whereas digoxin and warfarin were more commonly prescribed in the no anemia group.

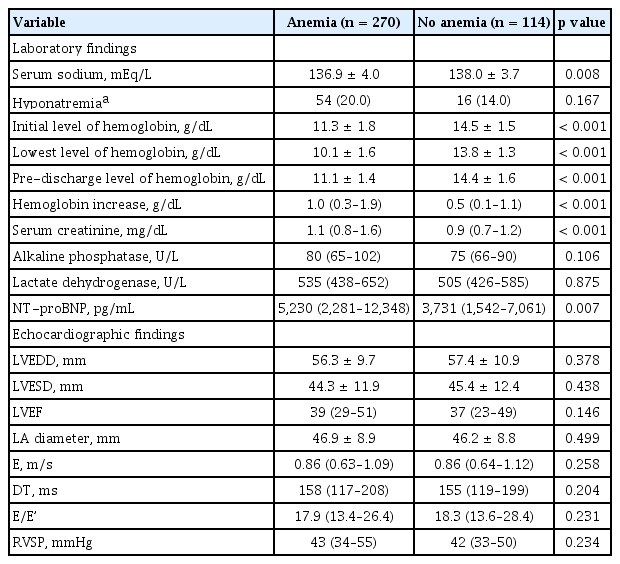

Laboratory and echocardiographic findings

Laboratory and echocardiographic findings are summarized in Table 2. The levels of Hgb throughout the hospitalization period were significantly lower, and the levels of serum creatinine and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide were significantly higher, in the anemia group than in the no anemia group. Echocardiographic findings were not different between the groups.

Clinical outcomes

During clinical follow-up (528 days; interquartile range, 205 to 743), 60 patients (15.6%) died and 131 patients (34.1%) were re-hospitalized due to worsening of HF.

All-cause mortality and HF-related re-hospitalization were not different between the anemia and no anemia groups (17.8 vs. 10.5%, p = 0.074; 35.2 vs. 31.6%, p = 0.496, respectively). In Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis, all-cause mortality was significantly higher in the anemia group than in the no anemia group (log-rank p = 0.035) (Fig. 1), but HF-related re-hospitalization was not different between the groups.

Death-free survival (A) and heart failure re-hospitalization-free survival (B) on Kaplan-Meier analysis according to the presence of anemia during hospitalization.

Neither anemia at admission nor pre-discharge anemia was associated with all-cause mortality or re-hospitalization during clinical follow-up (Fig. 2). In Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis, pre-discharge anemia showed a significant association with increased mortality compared to no pre-discharge anemia, but admission anemia was not associated with increased mortality during clinical follow-up (Fig. 3).

Death and heart failure (HF) re-hospitalization according to the presence of admission anemia (A) and pre-discharge anemia (B).

Independent predictors of clinical outcomes

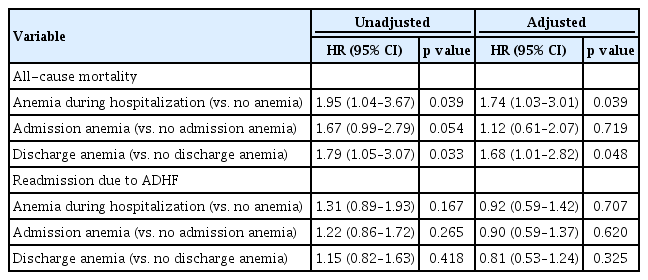

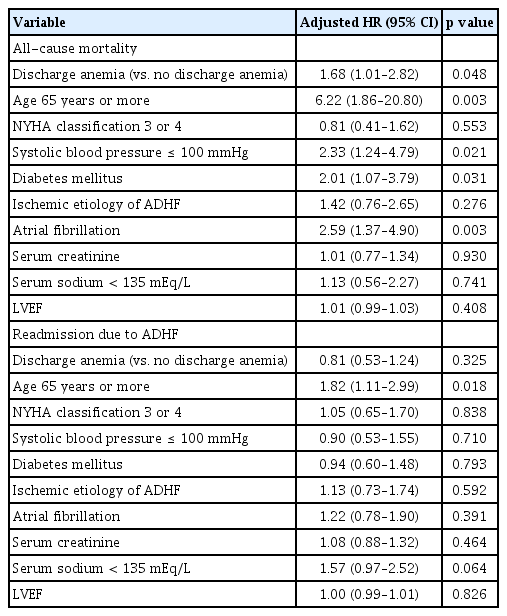

Anemia during hospitalization was a significant predictor of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 1.74; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03 to 3.01; p = 0.039). Pre-discharge anemia was also an independent predictor of future mortality (adjusted HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.82; p = 0.048), but anemia at admission was not a predictor of increased mortality (adjusted HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.61 to 2.07; p = 0.719) (Table 3). Neither admission nor pre-discharge anemia predicted HF-related re-hospitalization. Old age (≥ 65 years), diabetes mellitus, hypotension, and atrial fibrillation were also independent predictors of mortality, but old age (≥ 65 years) was the only independent predictor of HF-related re-hospitalization (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

The authors investigated the impact of the timing of anemia during hospitalization on future clinical outcomes in surviving ADHF patients from an index HF, and the principal findings of the present study were as follows: (1) anemia is highly prevalent (70.3%) and a predictor of future mortality in patients with ADHF; (2) pre-discharge anemia, rather than anemia at admission, is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with ADHF after surviving discharge; and (3) neither anemia at admission nor pre-discharge anemia is associated with HF-related re-hospitalization in patients with ADHF.

Numerous studies have evaluated the association between anemia and clinical outcomes in patients with HF; however, most studies examined the prognostic impact of anemia in chronic HF [15-18]. Furthermore, studies on anemia in ADHF patients have examined the prognostic impact of anemia at a single time point, generally at the time of presentation [1-4]. To the best of our knowledge, few studies have evaluated the clinical impact of anemia at different times during hospitalization. Stojcevski et al. [6] showed that discharge Hgb was related to re-hospitalization but not mortality in patients with ADHF. Other study reported that a change in the level of Hgb during hospitalization was independently associated with clinical outcomes in ADHF [7]. We found that only anemia at discharge increased all-cause mortality; however, neither anemia at admission nor discharge affected the readmission rate due to worsening of ADHF. In contrast with the results of the abovementioned study [6], discharge anemia was not associated with readmission due to ADHF in our study, and this difference in clinical outcome between the two studies may be related to several factors, such as different LVEF or ethnicity of the sample. Because both are small retrospective studies, works with larger, real-world registries or randomized trials are needed to further explore this issue. In the current study, transfusion was performed in 53 patients (13.8%), and more patients with anemia received transfusion than those without anemia (17.0% vs. 6.1%, p = 0.005). Transfusion also affected the study results similarly to the original analysis, in terms of death (HR, 1.89 for transfusion; 95% CI, 1.02 to 3.50; p = 0.042) and HF-related readmission (HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.74; p = 0.862). However, we believe that transfusion itself was not a predictive factor for clinical outcomes, but rather a supportive treatment for anemia. Therefore, we did not include it in the multivariate model.

Reasons for higher mortality in ADHF patients with discharge anemia were probably multifactorial (e.g., a higher prevalence of ischemic heart disease in the anemia group). Patients with coronary artery disease should be prescribed an antiplatelet indefinitely, irrespective of the recanalization state of the infarct-related artery, thereby triggering iron deficiency anemia [19,20]. However, admission anemia did not influence mortality in our study, emphasizing the importance of discharge anemia in ADHF. The main reason for this is probably that patients could not manage anemia after discharge. Current guidelines for ADHF do not set an optimal target range of Hgb in patients with ADHF and anemia during hospitalization [10,11]. Furthermore, hemoconcentration also positively affects clinical outcomes in ADHF [7,21,22]. In one study, hemoconcentration occurring late during hospitalization was only associated with improved survival in patients with ADHF compared to early hemoconcentration, and this finding intensified the results of the current study [23]. However, physicians may not be able to transfuse a sufficient amount of red blood cell to raise the Hgb level up to an anemic range in real world clinical practice, because of insurance issues or volume overload. Therefore, the optimal target range of Hgb should be established using large-scale registries in these high-risk patients.

The main limitation of the present study was that it used a retrospective, single-center design and included a relatively small number of patients. Second, management for anemia was not standardized in our study population. However, patients were managed with transfusion to raise the level of Hgb above 7 g/dL according to the treatment guidelines for anemia, and not for HF [24]. Third, we could not evaluate the revascularization state of ischemic heart disease in our study population. Considering the high prevalence (36.2%) of ischemic heart disease as an etiology of ADHF, revascularization of an infarct-related artery may have influenced our clinical outcomes. Fourth, there were no laboratory data on iron deficiency. Therefore, anemia was probably partly associated with hemodilution. The type of anemia, such as iron deficiency anemia, anemia with chronic disease, or anemia with acute blood loss, was not fully evaluated. Finally, although we adjusted for multiple confounding factors, we cannot exclude the possibility of residual confounding factors, as a result of the presence of an unmeasured confounder or measurement errors in the included factors.

KEY MESSAGE

1. The presence of anemia during hospitalization was associated with increased mortality, but not the re-hospitalization rate, in patients with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF).

2. Anemia at admission did not predict increased mortality or re-hospitalization rate. Only anemia at discharge time was associated with increased mortality in patients with ADHF.

3. The identification and optimal management of anemia during hospitalization will be important in patients with ADHF to reduce mortality.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (HI15C0498), and grants of National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Korea government (2015M3A9B4051063, 2015M3A9B4066496, 2016R1D1A1A09917796), by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the NRF funded by the Korean government, MSIP (2017M3A9E8023001) and by a grant (CRI13901-22.1) Chonnam National University Hospital Biomedical Research Institute.