Management of inflammatory bowel disease beyond tumor necrosis factor inhibitors: novel biologics and small-molecule drugs

Article information

Abstract

The incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), comprising Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, have increased in Asia and developing countries. In the past two decades, anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents have revolutionized the treatment of IBD, in part by decreasing the rates of complications and surgery. Although anti-TNF agents have changed the course of IBD, there are unmet needs in terms of primary and secondary non-responses and side effects such as infections and malignancies. Novel biologics and small-molecule drugs have been developed for IBD, and the medical treatment options have improved. These drugs include sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulators and anti-integrins to block immune cell migration, and cytokine and Janus kinase inhibitors to block immune cell communications. In this review, we discuss the approved novel biologics and small-molecule drugs, including several of those in the late stages of development, for the treatment of IBD.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), comprising ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), is chronic and progressive and requires life-long treatment. IBD is prevalent in the west, and its incidence and prevalence are increasing in Asia [1–4]. Despite our enhanced understanding of dysregulated immune responses and the impaired colonic epithelial system [5,6], treatment of IBD is challenging.

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) blockers were introduced in the late 1990s and have markedly improved the treatment of IBD [7]. Anti-TNF agents facilitate symptom control, thereby improving quality of life, and change the course of IBD [8–10]. However, up to a third of IBD patients do not initially respond to anti-TNF agents, and another third lose their response during maintenance therapy [11,12]. Furthermore, although anti-TNF agents have acceptable safety profiles, there are concerns regarding opportunistic infections, elevations of liver enzymes, and malignancies [7,13]. Clinical trials of novel drugs have demonstrated their efficacy and safety [14]. Novel drugs may overcome the limitations of anti-TNF agents and be useful for patients in whom treatment with such agents has failed. Here, we review recent biologics and small-molecule drugs (SMDs) to facilitate evidence-based drug therapy for IBD.

MECHANISMS OF ACTION OF APPROVED NOVEL BIOLOGICS AND SMDs

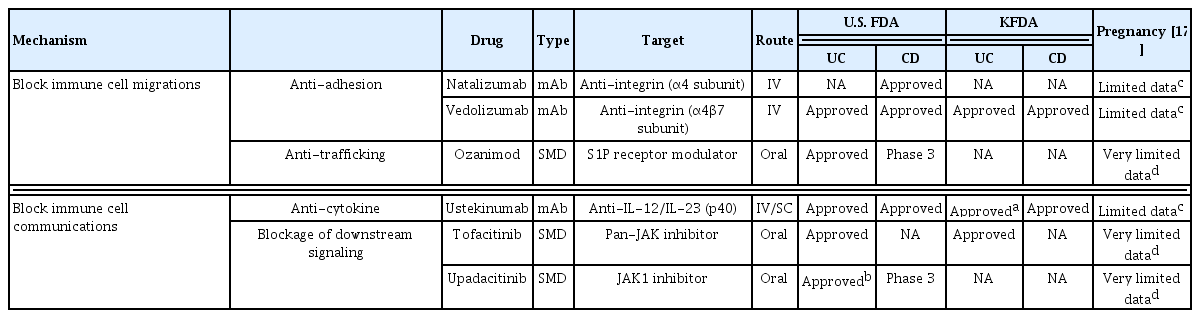

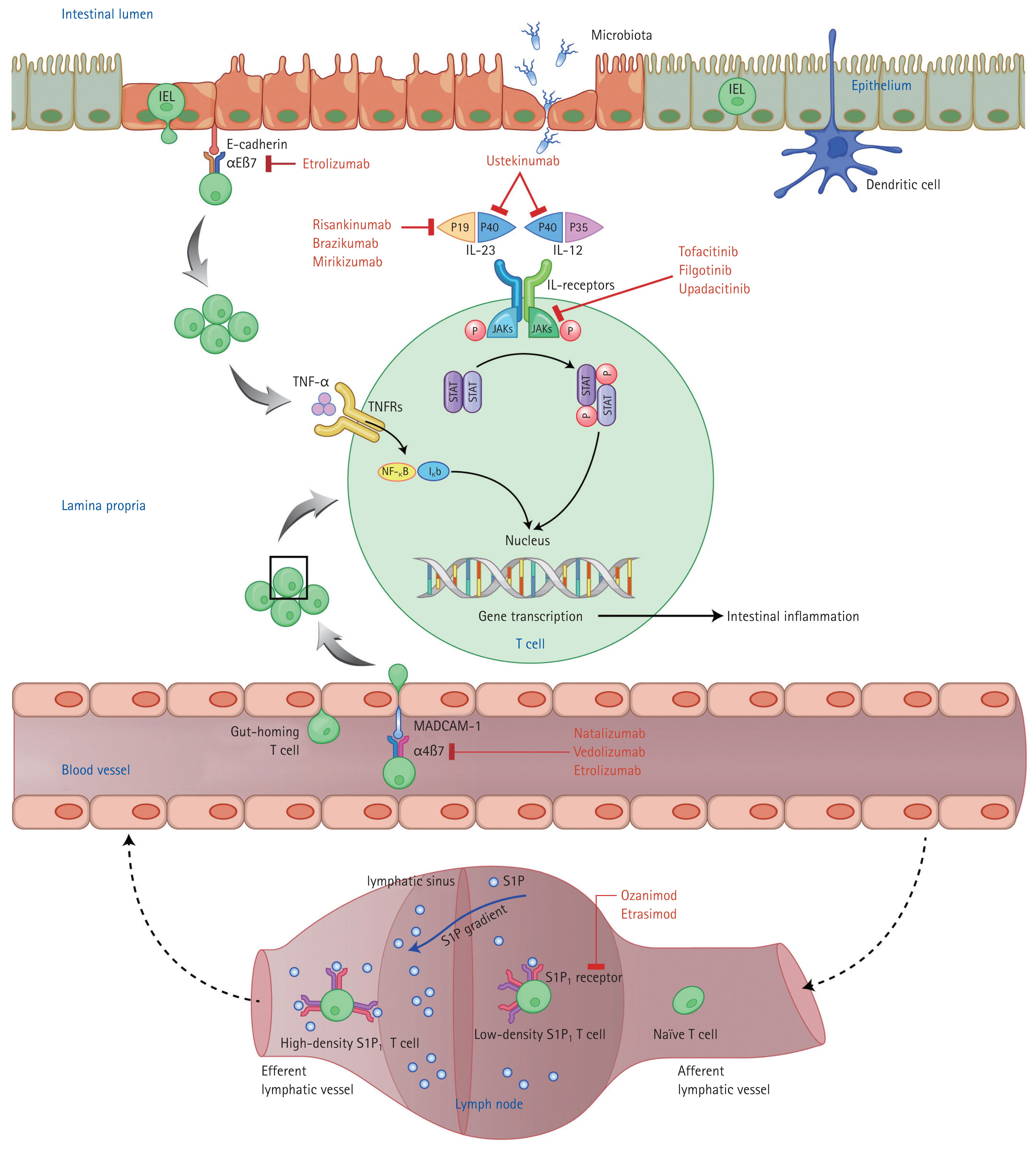

Biologics are proteins produced by living organisms that control the activities of other proteins and modulate cellular processes. Biologics are large, complex molecules and are administered intravenously or subcutaneously. By contrast, SMDs are of low molecular weight (< 1 kDa) and are synthesized chemically. SMDs pass easily through cell membranes and have a short half-life. Therefore, SMDs can be administered orally and are non-immunogenic [15]. Novel, approved monoclonal antibodies and SMDs for IBD include anti-integrins, anti-interleukins (ILs), Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulators [16]; these block immune cell communication or migration. The mechanisms of action of approved novel biologics and SMDs (Table 1) [17] in IBD are shown in Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of action of novel biologics and small-molecule drugs for inflammatory bowel disease. Modified from Na et al. [16], with permission. IEL, intraepithelial lymphocyte; JAK, Janus kinase; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNFR, tumor necrosis factor receptor; STAT, signal transducers and activators of transcription; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; MAdCAM-1, mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule-1; S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate.

BLOCKING OF IMMUNE CELL MIGRATION

Active IBD, i.e., chronic intestinal inflammation, is characterized by continuous migration of lymphocytes from the bloodstream to the gut mucosa [18]. Immune cell migration into the gut mucosa can be suppressed by inhibitors of lymphocyte trafficking from regional lymph nodes to the bloodstream and of adhesion to the gut mucosa. Lymphocytes in regional lymph nodes migrate into the bloodstream along a concentration gradient of S1P, a bioactive sphingolipid [19]. The five subtypes of the S1P receptor (S1PR) are found on the surface of lymphocytes. Stimulation of S1PR on lymphocytes results in degradation of the target receptor [20], decreasing the number of activated lymphocytes entering the bloodstream from lymphoid organs [21]. Interactions between integrins (surface molecules on T lymphocytes) and ligands (mucosal vascular addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 [MAdCAM-1]) on the surface of endothelial cells facilitate lymphocyte recruitment from the bloodstream into gut tissue [22]. Integrin inhibitors prevent lymphocyte infiltration of the gut mucosa, known as gut homing.

OZANIMOD (S1PR MODULATOR)

Ozanimod is an oral SMD and a selective modulator of S1PR1 and S1PR5, mainly S1PR1 [23]. A phase 2 trial (TOUCHSTONE) evaluated the therapeutic effect of ozanimod in 197 patients with moderate-to-severe UC [24]. The patients were assigned to receive placebo or 0.5 or 1 mg ozanimod once daily after a 1-week dose escalation. At 8 weeks, the 1 and 0.5 mg doses resulted in clinical remission in 16% (p = 0.048) and 14% (p = 0.14) of patients, respectively, compared with 6% of patients given the placebo. At 32 weeks, the clinical remission rate was increased to 21% in the 1 mg ozanimod group (p = 0.01) and to 26% in the 0.5 mg group (p = 0.002), compared with 6% in the placebo group. Interestingly, the absolute lymphocyte count in blood decreased by 49% and 32% in the 1 and 0.5 mg groups, respectively. Ozanimod was well tolerated, and headache and anemia were the most common adverse effects. Of 197 TOUCHSTONE subjects, 170 participated in the TOUCHSTONE open-label extension study for > 4 years [25]. The rate of discontinuation was 28% during year 1 and 15%–18% during years 2–4; no new safety issue was observed during the study period.

The True North phase 3 trial of ozanimod as an induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe UC comprised cohort 1 (645 patients; ozanimod 1 mg once daily or placebo) and cohort 2 (367 patients; only ozanimod 1 mg once daily) [26]. Maintenance treatment was conducted up to week 52 by randomizing the clinical responders. At 10 weeks, ozanimod showed significantly higher rates of clinical remission (18.4% vs. 6.0%), clinical response (47.8% vs. 25.9%), and endoscopic improvement (27.3% vs. 11.6%) compared with placebo (all p < 0.001). At 52 weeks, ozanimod had higher rates of clinical remission (37.0% vs. 18.5%), clinical response (60.0% vs. 41.0%), and endoscopic improvement (45.7% vs. 26.4%) compared with placebo (all p < 0.001). The infection rate was higher in the ozanimod group than the placebo group during the maintenance period (23.0% vs. 11.9%); however, in both groups, the rate of serious infections was < 2% up to week 52. An ongoing open-label extension study is evaluating the longterm efficacy and safety profile of ozanimod.

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved ozanimod for moderate-to-severe UC in May 2021, but it has not yet been approved in South Korea. Ozanimod requires a 7-day titration (0.25 mg on days 1–4, 0.5 mg on days 5–7, and then 1 mg once daily) to reduce the risk of bradycardia, which has been reported for some S1P modulators within several hours of the first dose [27].

The STEPSTONE phase 2 trial involving 69 patients with moderate-to-severe CD treated with 1 mg ozanimod once daily showed an endoscopic response rate of 23.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.9 to 34.9) at 12 weeks [28]. The YELLOWSTONE phase 3 trial of ozanimod in patients with moderate-to-severe CD is ongoing and will be followed by a long-term open-label study.

NATALIZUMAB (ANTI-INTEGRIN α4 SUBUNIT)

Natalizumab is a non-selective immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) monoclonal antibody against the α4 subunit of integrin, and thus it blocks both α4β7 and α4β1 [22]. Natalizumab interferes with the gut-specific α4β7/MAdCAM-1 interaction, thereby blocking lymphocyte accumulation in the inflamed intestinal mucosa. Pivotal phase 3 trials [29] showed natalizumab to be effective as an induction (ENACT-1) and maintenance (ENACT-2) therapy for moderate-to-severe CD. In the phase 3 ENCORE trial, natalizumab had a higher clinical response rate than that of the placebo [30].

Natalizumab inhibits the migration of T lymphocytes (α4β1) to the central nervous system [31], suppressing antiviral immunity and inducing a life-threatening adverse effect: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) [29,32,33]. In January 2008, the FDA approved natalizumab for induction and maintenance treatment of moderate-to-severe CD, but neither the European nor the South Korean regulatory authority has yet followed suit. FDA included in the drug label a warning to not use natalizumab in combination with immunosuppressants or anti-TNF agents because of the risk of PML.

VEDOLIZUMAB (ANTI-INTEGRIN α4β7 SUBUNIT)

Vedolizumab is a selective IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to α4β7 integrin, which is expressed only on intestinal T lymphocytes. Vedolizumab inhibits the α4β7 integrin–MadCAM-1 interaction, inducing a gut-specific anti-inflammatory effect [18]. Phase 3 trials of GEMINI-1 (UC) and GEMINI-2 (CD) showed the efficacy of vedolizumab as an induction and maintenance therapy. In GEMINI-1, vedolizumab induction therapy resulted in a significantly higher clinical response rate at 6 weeks (47.1%, 106/225 patients) compared with placebo (25.5%) (p < 0.001) (cohort 1) [34]. As maintenance therapy for 373 induction responders in cohorts 1 and 2, the clinical remission rates at 52 weeks were 41.8% and 44.8% of patients treated with vedolizumab every 8 and 4 weeks, respectively, compared with 15.9% of patients given the placebo (p < 0.001) [34]. In the similar GEMINI-2 trial involving 368 patients with moderate-to-severe CD, the clinical remission rate was 14.5% (32/220) for vedolizumab and 6.8% (10/148) for placebo (p = 0.02) in cohort 1 at 6 weeks. At 52 weeks, the clinical remission rates were 39.0% (p < 0.001) and 36.4% (p = 0.004) among responders in cohorts 1 and 2 treated with vedolizumab every 8 and 4 weeks, respectively, compared with 21.6% for placebo [35]. In subgroup analyses of the GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trial data, the therapeutic efficacy and safety of vedolizumab were similar in Asian and non-Asian patients with UC and CD [36,37], suggesting the efficacy of vedolizumab to be consistent. This finding is supported by a pharmacokinetic study revealing that the pharmacokinetic parameters of vedolizumab were similar in Asian and non-Asian patients with moderate-to-severe UC and CD [38].

In post hoc analyses of GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2, vedolizumab showed greater efficacy in patients naïve to anti-TNF agents than in those with prior anti-TNF agent exposure [39,40]. In the GEMINI-3 trial, the clinical remission rate was higher after vedolizumab compared with placebo treatment (26.6% vs. 12.1%, p = 0.001) in 315 patients with CD in whom prior anti-TNF agent therapy failed [41]. Among South Korean patients with CD or UC in whom anti-TNF agent therapy failed, the clinical remission rate of vedolizumab as induction therapy was 44.1% for CD and 44.0% for UC [42].

The VARSITY trial, the first head-to-head biological comparative study in IBD, showed the efficacy of vedolizumab (31.3%) to be superior to that of adalimumab (22.5%) for moderate-to-severe UC up to 52 weeks (p = 0.006) [43]. However, no benefit was observed in patients who failed therapy with anti-TNF agents other than adalimumab (20.3% vs. 16.0%; 95% CI, −78 to 16.2). In addition, the study had several limitations. First, the rate of anti-TNF agent therapy was up to 25%, but prior exposure to anti-MAd-CAM agents, including vedolizumab and natalizumab, was prohibited. Second, no dose escalation was allowed. Third, no data on early efficacy were reported. Fourth, the steroid-free remission rate was higher in the adalimumab group than the vedolizumab group.

Vedolizumab might have a slow onset of action in patients with CD, although anti-TNF-naïve patients reportedly show improvement in patient-reported symptoms by week 2 [44]. Vedolizumab is an anti-integrin that blocks gut homing by lymphocytes, and immune cells already present in inflamed tissue require time to eliminate. Therefore, concomitant treatment with steroids could be considered in patients with CD with a high inflammatory burden who require a rapid clinical response. In addition, because of its gut specificity, IBD patients with extraintestinal symptoms may not benefit from vedolizumab. In perianal fistulizing CD, the phase 4 ENTERPRISE trial showed that 53.6% of patients on vedolizumab achieved a ≥ 50% decrease in perianal fistula at 30 weeks [45]. In a meta-analysis of four studies involving 198 patients, vedolizumab promoted perianal fistula healing in almost one-third of the patients [46].

With regard to safety, because of its gut specificity [47], unlike natalizumab, vedolizumab does not act on T lymphocytes in the central nervous system [48]. In the GEMINI study of long-term safety, vedolizumab did not increase the risk of infection, PML, malignancy, or hepatic events [49]. Therefore, vedolizumab may be a good therapeutic option for elderly IBD patients and those at high risk of infection or malignancy [50]. Despite a theoretical concern, enteric infections were infrequent, and perioperative complications of bowel surgery were not increased by vedolizumab [47,51]. The FDA approved vedolizumab in May 2014 for the treatment of patients with moderate-to-severe UC or CD who do not respond to conventional treatments or anti- TNF agents. In South Korea, vedolizumab was approved in August 2017 for patients with moderate-to-severe UC or CD, and it has been reimbursed as a first-line therapy since August 2020.

BLOCKADE OF IMMUNE CELL COMMUNICATION

IL-12 p35-p40 and IL-23 p19-p40, which share a common p40 subunit, are proinflammatory heterodimeric cytokines that mediate cellular immunity. IL-12 induces the differentiation of naïve T cells to T helper 1 (Th1) cells, and IL-23 induces their differentiation to Th17 cells [52]. IL-12/23 inhibitors downregulate proinflammatory cytokines and inflammatory pathways in IBD.

The JAK family of intracellular signal mediators comprises four members (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2). JAKs interact with signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT) [53], and the JAK/STAT signaling pathway regulates the transcription of several cytokine-encoding genes [54] and is critical for T-cell immune responses [55]. Thus, inhibition of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway can ameliorate intestinal inflammation.

USTEKINUMAB (ANTI-IL-12/IL-23)

Ustekinumab is a fully human IgG1k monoclonal antibody that binds to the shared p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23. Ustekinumab blocks T-lymphocyte activation, suppressing inflammation [56]. In phase 3 trials, ustekinumab was investigated as an induction therapy for moderate-to-severe CD in patients after anti-TNF therapy failure (UNITI-1; 741 patients) or conventional therapy failure (UNITI-2; 627 patients), and as a maintenance therapy in patients with a clinical response to induction therapy (IM-UNITI; 388 patients) [57]. At 6 weeks, the clinical response rates of ustekinumab at 130 mg (34.3%) or 6 mg/kg (33.7%) were significantly higher than that of the placebo (21.5%) in UNITI-1 (p ≤ 0.003) and UNITI-2 (51.7% or 55.5% vs. 28.7%; p < 0.001 for both). In IM-UNITI, the clinical remission rate after maintenance treatment (for induction responders) with ustekinumab every 8 or 12 weeks was superior to that after placebo treatment at 44 weeks (53.1% or 48.8% vs. 35.9%; p = 0.005 or p = 0.04, respectively). The results of UNITI-1 and UNITI-2 indicate ustekinumab to be effective for moderate-to-severe CD irrespective of the prior response to anti-TNF agents or conventional treatments. However, ustekinumab is expected to have superior efficacy in anti-TNF agent-naïve patients than in those in whom such agents failed to induce a response [57,58]. In a real-world cohort study, ustekinumab showed therapeutic efficacy in terms of the clinical response rate at 8 months (58.5% [24/41]) irrespective of the selection criteria [59]. In addition, ustekinumab induced clinical remission and endoscopic improvement in pediatric patients with CD with anti-TNF therapy failure [60].

In moderate-to-severe UC, the UNIFI phase 3 trial investigated induction and maintenance therapy with ustekinumab [61]. In total, 961 patients received one dose of 130 mg or 6 mg/kg ustekinumab or placebo. Approximately 50% of the patients in each group had failed prior biologic therapy. At 8 weeks, 130 mg and 6 mg/kg ustekinumab showed significantly higher clinical remission rates compared with the placebo (15.6% and 15.5% vs. 5.3%; p < 0.001). Subsequently, 523 responders to induction therapy received maintenance treatment of 90 mg ustekinumab every 8 or 12 weeks or placebo. At 44 weeks, the clinical remission rate for 90 mg ustekinumab every 8 weeks (43.8%, p < 0.001) or 12 weeks (38.4%, p = 0.002) was significantly higher than that achieved by the placebo (24.0%). Among patients who failed prior biologics, ustekinumab also showed superior clinical remission rates compared with the placebo for induction (11.6% and 12.7% vs. 1.2%, respectively) and maintenance (39.6% and 22.9% vs. 17.0%, respectively). Notably, at 8 weeks, 6 mg/kg ustekinumab showed a similar difference in the clinical remission rate compared with placebo irrespective of prior biologic failure (difference, 11.5% [12.7% to 1.2%]) or not (difference, 8.5% [18.4% to 9.9%]). In a subgroup analysis of 133 East Asian patients in the UNIFI study, 130 mg and 6 mg/kg ustekinumab showed higher clinical remission rates at 8 weeks compared with the placebo (11.4% and 11.1% vs. 0%), indicating that ustekinumab is effective in East Asian patients compared with the overall population [62].

Ustekinumab can provide a clinical benefit within 3 weeks [57], making it an alternative to anti-TNF agents for patients with moderate-to-severe CD and a high inflammatory burden who require a rapid therapeutic response. In addition, ustekinumab blocks proinflammatory cytokine pathways, suggesting its potential efficacy for extraintestinal manifestations such as psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis. The incidence of the presence of antidrug antibodies was 2.3% (27/1,154) in UNITI and 4.6% (23/505) in UNIFI at 44 weeks [57,61]. Combination therapy of ustekinumab with immunomodulators might not be necessary due to the low immunogenicity, although data are sparse.

In the UNITI and UNIFI studies, the side effects of ustekinumab were similar to those of placebo [57,61]. In the IM-UNITI long-term extension study, ozanimod had a comparable safety profile with that of the placebo up to 96 weeks [63]. Only one case of pulmonary tuberculosis in an endemic area was reported [63]. Long-term clinical data demonstrated that serious infections and malignancies are rare [64,65]. Ustekinumab has been approved by the FDA for moderate-to-severe CD (September 2016) and UC (October 2019). In South Korea, ustekinumab was approved as a first-line drug with reimbursement for moderate-to-severe CD in December 2018 and for moderate-to-severe UC in November 2019; however, reimbursement for the latter covers its use only as a second-line drug.

TOFACITINIB (PAN-JAK, MAINLY JAK1/JAK3, INHIBITOR)

Tofacitinib is an oral SMD that inhibits JAK1 and JAK3, blocking the downstream JAK/STAT signaling pathway and thus modulating DNA transcription [66]. In phase 3 trials, tofacitinib showed clinical efficacy for induction (OCTAVE-1 and OCTAVE-2) and maintenance (OCTAVE sustain) therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe UC and prior exposure to conventional therapies or anti-TNF agents [67]. In OCTAVE-1 (598 patients), the clinical remission rate was 18.5% (88/476) for 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily compared with 8.2% (10/122) for placebo (p = 0.007) at 8 weeks; in OCTAVE-2 (541 patients), the clinical remission rate was 16.6% for tofacitinib and 3.6% for placebo (p < 0.001). In total, 593 patients who responded to induction therapy participated in OCTAVE sustain. At 52 weeks, the clinical remission rate was 34.3% for 5 mg tofacitinib twice daily and 40.6% for 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily, compared with 11.1% for placebo (p < 0.001 for both). In the extension trial of induction with 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily up to week 16 (OCTAVE Open), 52.2% of patients who did not respond at 8 weeks showed a delayed response; of these patients, 56.1% maintained a clinical response at 36 months [68]. In subgroup analyses of the OCTAVE trial involving East Asian patients with UC, compared with the placebo, tofacitinib showed greater efficacy as an induction and maintenance therapy, with a similar safety profile [69]. By contrast, two phase 2 trials of tofacitinib for moderate-to-severe CD failed to demonstrate clinical efficacy as an induction and maintenance therapy [70].

Notably, in the OCTAVE trial, treatment efficacy was similar irrespective of prior use of anti-TNF agents. In addition, tofacitinib induced a clinical response within 2 weeks. Post hoc analyses of the OCTAVE1 and 2 results showed that stool frequency and rectal bleeding decreased in approximately one-third of patients with moderate-to-severe UC within 3 days [71]. In the GETAID cohort in France, salvage therapy with 10 mg tofacitinib twice daily was evaluated in 55 patients with refractory acute severe UC [72]. The incidence of colectomy at 3 months in the GETAID cohort was comparable with that in the infliximab or cyclosporine treatment groups. These data enable prediction of the long-term efficacy of tofacitinib [73].

Regarding safety, tofacitinib might increase the risk of infection by blocking multiple cytokine pathways. In the OCTAVE trial, more infectious events, including herpes zoster, occurred with tofacitinib [67]. Long-term (4.4 years) data from global clinical trials of tofacitinib, however, demonstrated a safety profile similar to those of other biologics, and the incidence of herpes zoster infection was dose-dependently higher with tofacitinib (4.1; 95% CI, 3.1 to 5.2) [74]. Therefore, to prevent herpes zoster infection, combination therapy with other immunomodulators should be avoided.

In May 2018, the FDA approved tofacitinib for the treatment of moderate-to-severe UC. Post-marketing surveys reported that the risk of venous thromboembolism was higher in patients receiving 10 mg twice daily than in those receiving 5 mg twice daily among patients with more than one cardiovascular disease risk factor over 50 years of age [75]. For a dosage of 10 mg twice daily, the FDA inserted a warning box in Feb 2019, and the European Medicines Agency has issued a caution. A recent, randomized safety trial reported that tofacitinib, compared with anti-TNF agents, increased the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [76]. In September 2021, the FDA recommended that warnings should be provided regarding the increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events associated with JAK inhibitors used for chronic inflammatory diseases [77]. Therefore, the benefits and risks should be considered when using high-dose tofacitinib for long-term maintenance therapy. The FDA suggests reserving tofacitinib for patients who are intolerant or do not adequately respond to anti-TNF agents [77]. In September 2018, tofacitinib was approved in South Korea as a first-line drug for moderate-to-severe UC.

UPADACITINIB (JAK1 INHIBITOR)

Upadacitinib is an oral SMD and a selective JAK1 inhibitor. The U-ACHIEVE program comprises three studies: a phase 2b dose-ranging induction study, a phase 3 dose-confirming induction study, and a phase 3 maintenance study (U-ACHIEVE maintenance). The phase 2b study demonstrated the efficacy of upadacitinib as an induction therapy in 250 patients with moderate-to-severe UC [78], 73.2% of whom had prior exposure to anti-TNF agents. At 8 weeks, the clinical remission rates after treatment with 7.5, 15, 30, and 45 mg upadacitinib once daily were 8.5% (p = 0.052), 14.3% (p = 0.013), 13.5% (p = 0.011), and 19.6% (p = 0.002), respectively, compared with placebo (0%). The endoscopic improvement rates were 14.9%, 30.6%, 26.9%, and 35.7%, respectively, which were also significantly higher than that of the placebo (2.2%) (p = 0.033, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.001, respectively). Notably, onset of action was rapid, manifesting at 2 weeks. Upadacitinib showed comparable safety with that of the placebo, and the adverse event rate was < 5%. The phase 3 U-ACHIEVE and U-ACCOMPLISH induction trials evaluated 45 mg upadacitinib once daily for 8 weeks, and the U-ACHIEVE maintenance trial assessed 15 or 30 mg once daily up to 52 weeks; these three trials are ongoing.

The FDA in March 2022 approved 45 mg upadacitinib once daily for 8 weeks as a second-line induction therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe UC who had failed or were intolerant to anti-TNF agents. The recommended dose of upadacitinib for maintenance is 15 mg once daily. However, 30 mg once daily can be used for patients with refractory or severe disease. The Korean FDA is expected to approve upadacitinib in the near future.

Upadacitinib showed superior efficacy to that of the placebo as induction therapy in 220 patients with moderate-to-severe CD in the phase 2 CELEST trial [79]. Patients were randomly assigned to 3, 6, 12, or 24 mg twice daily and 24 mg once daily or placebo. At 16 weeks, only 6 mg twice daily achieved a significantly higher clinical remission rate than that of the placebo (27% vs. 11%, p < 0.1). However, the endoscopic remission rate was 10% for 3 mg (p < 0.1), 8% for 12 mg (p < 0.1), and 22% for 24 mg (p < 0.01) upadacitinib twice daily and 14% for 24 mg upadacitinib once daily (p < 0.05), compared with 0% for placebo. The endoscopic remission rate of upadacitinib showed a dose-response relationship during the induction period. The 3.5-year CELEST open-label extension study (phase 2) showed sustained efficacy and a comparable safety profile for upadacitinib [80]. Several phase 3 trials of upadicitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for moderate-to-severe CD are ongoing.

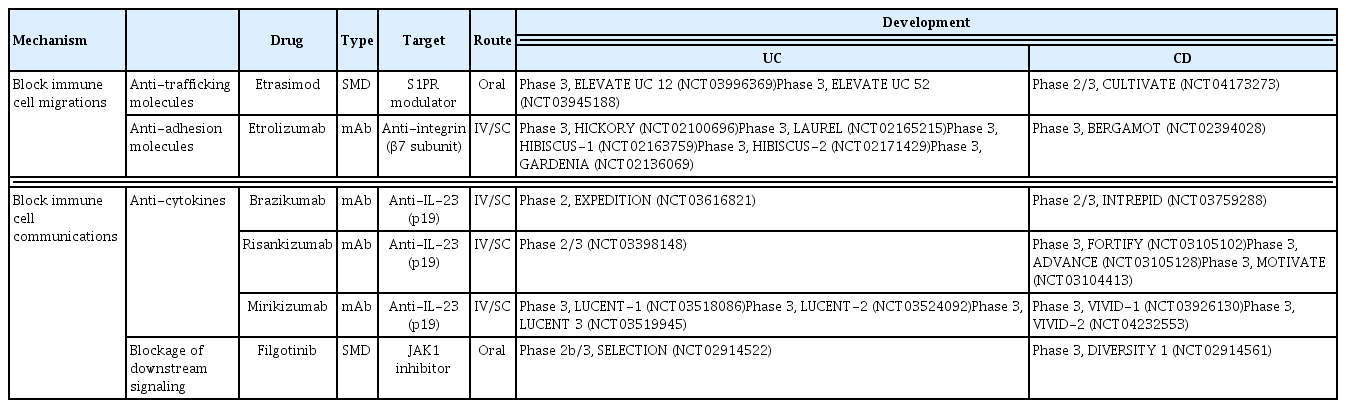

PROMISING BIOLOGICS AND SMDs IN LATE-PHASE DEVELOPMENT

Several promising biologics and SMDs are under investigation in clinical trials (Table 2). Selective blockers of the IL-23 p19 subunit, such as brazikumab, risankizumab, and mirikizumab, have shown efficacy against CD. In a phase 2 study of brazikumab involving 119 CD patients in whom prior anti- TNF agent therapy failed, the clinical response rate at 8 weeks was 49.2% for brazikumab compared with 26.7% for placebo (95% CI, 5.6 to 39.5; p = 0.010) [81]. In a phase 2 study involving patients with active CD, risankizumab, a selective inhibitor of IL-23 p19, had a higher clinical remission rate (31%) than that of the placebo (15%) (95% CI, 0.1 to 30.1; p = 0.0489) at 12 weeks [82]. In a phase 2 study of moderate-to-severe UC, at 12 weeks, the clinical response rate of mirinkisumab (41.3% for 50 mg, p = 0.014; 59.7% for 200 mg, p < 0.001; 49.2% for 600 mg, p = 0.001) was significantly and dose-dependently higher than that of the placebo (20.6%) [83]. In addition, treatment with mirikizumab at 600 and 1000 mg for a further 12 weeks had a clinical response rate of approximately 50% among patients who were initially non-responders [84]. In a phase 2 study of moderate-to-severe CD (SERENITY), at 12 weeks, mirikizumab at 600 and 1,000 mg had significantly higher endoscopic response rates than that of the placebo (p = 0.003, p < 0.001, respectively). The endoscopic response remained evident at 52 weeks [85].

Filgotinib is an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor with once daily dosing. In the SELECTION phase 2b/3 trial of filgotinib for active UC, the clinical remission rate at 10 weeks was higher for 200 mg filgotinib than for placebo (26.1% vs. 15.3%). The clinical remission rate at 58 weeks was 37.2% for filgotinib compared with 11.2% for placebo, demonstrating the efficacy of filgotinib for the induction and maintenance of clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe UC [86]. In the FITZROY phase 2 study for active CD, 47% of patients (60/128) treated with 200 mg filgotinib achieved clinical remission at 10 weeks compared with 23% of patients (10/44) given the placebo (p = 0.0077) [87]. Filgotinib impaired spermatogenesis by causing testicular atrophy/degeneration in an animal study [88]. Phase 2 studies of IBD (MANTA) and rheumatic disease (MANTA-Ray) are ongoing for this safety issue.

Etrolizumab is a non-selective IgG1 monoclonal antibody that blocks the β7 subunit of integrin α4β7, which binds to MAdCAM-1 and αEβ7, which in turn bind to E-cadherin [89]. Etrolizumab inhibits the homing of gut intraepithelial lymphocytes expressing αEβ7. In the HICKORY phase 3 trial involving 232 patients with UC with prior exposure to anti-TNF agents, subcutaneous etrolizumab at 105 mg every 4 weeks resulted in a higher clinical remission rate than did placebo (18.5% [71/384] vs. 6.3% [6/95], p = 0.003) at 14 weeks [90]. However, at 66 weeks (maintenance period), there was no difference compared with the placebo (24.1% vs. 20.2%, p = 0.50) among patients who responded during the induction period [90]. The LAUREL phase 3 trial involving patients with UC naïve to anti-TNF agents showed no significant difference compared with placebo at 62 weeks (maintenance period; 29.6% vs. 20.6%, p = 0.019) among patients who responded during the induction period [91]. In two identical phase 3 induction studies involving patients with UC naïve to anti-TNF agents, etrolizumab showed superior efficacy to that of placebo in HIBISCUS-1, but not in HIBISCUS-2 [92]. Indeed, etrolizumab showed similar efficacy in head-to-head comparisons to those of adalimumab and infliximab in patients with moderate-to-severe active UC [92,93].

Etrasimod is an oral SMD and a selective modulator of S1P1, S1P4, and S1P5. In the OASIS phase 2 study, the rate of improvement in the mean modified Mayo Clinic Score (stool frequency, rectal bleeding, and endoscopic findings) from baseline was higher for 2 and 1 mg etrasimod daily than for placebo (2.49 and 1.94 points vs. 1.50 points; p = 0.009 and p = 0.15) at 12 weeks [94]. Efficacy was maintained for a further 40 weeks, and the safety profile was favorable [95].

CONCLUSIONS

Although Asian and Western patients with IBD have different phenotypic and genetic characteristics, their responses to biologics and SMDs are similar [96]. Novel drugs have altered the goal of IBD therapy from clinical improvement to mucosal healing. The therapeutic options for IBD beyond anti-TNF agents are expanding rapidly. Although in IBD the term ‘remission’ is preferred to ‘cure,’ our ever-deepening understanding of its pathogenesis will facilitate the development of novel curative agents.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.