Pulsed field ablation: focused on atrial fibrillation ablation

Article information

Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained tachyarrhythmia and its increasing prevalence has resulted in a growing healthcare burden. Catheter ablation is indicated for patients with AF who are either refractory or intolerant to antiarrhythmic drugs or who exhibit decreased left ventricular systolic function. Catheter ablation can be categorized based on the energy source used, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA), cryoablation, laser ablation, and the recently emerging pulsed field ablation (PFA). PFA is anticipated to be promising owing to its tissue specificity, resulting in less collateral damage than thermal energy catheter ablations, such as RFA and cryoablation. In this review, we summarize the biophysical principles and clinical applications of PFA, highlighting its safety and efficacy profile compared to that with conventional thermal ablation.

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained tachyarrhythmia, with an increasing incidence and prevalence. Additionally, it is associated with an increased risk of stroke, heart failure, impaired quality of life, and dementia [1–6]. The global prevalence of AF is estimated to reach 50 million cases by 2020, with an increasing incidence worldwide, including in the United States and Europe [7–9]. In South Korea, the prevalence of AF has been steadily increasing, with projections indicating an increase of 5.81% by the year 2060 [3]. As reported in the Framingham Heart Study, the incidence of AF increases with age, with a lifetime risk of 26% in Caucasian men and 23% in Caucasian women over 40 years of age [10]. AF risk factors include modifiable (e.g., hypertension and obesity) and non-modifiable (e.g., age, sex, and family history) factors [11–15].

The ESC 2024 guidelines introduced the AF-CARE pathway, emphasizing a comprehensive approach to AF management [16]. In the past, rhythm control therapy for AF was not emphasized because of the lack of demonstrated benefits in major clinical trials, including the Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Sinus Rhythm Management and the comparison of rate control and rhythm control in patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation (PeAF) (RACE) trials. These studies found no significant advantage of rhythm control over rate control and instead reported higher rates of adverse events [17–22]. Since the EAST-AF-NET 4 trial and real-world data have highlighted the benefits of early rhythm control, interest in early interventions, including catheter ablation, has increased [23,24]. Although the optimal timing of catheter ablation for AF remains uncertain, several studies have explored its impact on clinical outcomes, with some suggesting the potential benefits of early intervention [25–30].

CONVENTIONAL THERMAL ENERGY ABLATION

Conventional thermal-energy ablation techniques, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and cryoballoon ablation (CBA), are the most widely used modalities, whereas hot balloon and laser balloon ablation are also utilized in selected cases. RFA uses an alternating current (typically 350–750 kHz) delivered through the catheter tip to generate resistive heating within the myocardial tissue [31,32]. This thermal energy denatures the proteins and induces coagulative necrosis. Over the years, open-irrigation catheters and contact force sensing technologies have significantly improved their safety and efficacy [33–38]. More recently, high-power, short-duration protocols (e.g., 50–90 W for ≤ 15 seconds) and very high-power, short-duration approaches (e.g., 90 W for ≤ 4 seconds) have been introduced to shorten the procedure time while minimizing collateral injury [39,40]. Nonetheless, RFA carries the risk of esophageal and phrenic nerve (PN) injury, particularly when the ablation is delivered in close proximity to these adjacent structures.

CBA delivers cryothermal energy through a balloon catheter and induces tissue injury via extracellular and intracellular ice formation. Temperatures between −10°C and −25°C primarily cause dehydration and acidification, whereas lower temperatures (< −50°C) result in direct cell membrane rupture. This single-shot technique is effective for pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) and offers a reduced risk of esophageal injury compared to RFA [41]. Recent data on second-generation cryoballoons demonstrated an acute PVI rate of 99–100% and a 1-year success rate ranging from 80% to 86%, highlighting its clinical efficacy [42–44]. However, CBA still poses risks of PN injury and incomplete lesion durability and is generally less flexible for substrate modification owing to its anatomical constraints [45].

Laser balloon ablation, such as the HeartLight™ system, utilizes an endoscope-guided compliant balloon that delivers adjustable laser energy (5.5–12 W) to the antral region of the pulmonary veins (PVs). This modality enables the direct visualization of the ablation site and real-time energy titration. While it has demonstrated efficacy comparable to other techniques, it also has limitations, including PN injury and, like other single-shot technologies, may have limited applicability in extensive substrate ablation.

Hot balloon ablation (HBA) delivers thermal energy through a compliant balloon filled with heated dilute contrast medium (typically 40–70°C), which is inflated at the PV antrum to achieve circumferential tissue heating [46,47]. This technique enables single-shot PVI by conforming to variable PV anatomies and creating contiguous lesions via thermal conduction. Early studies have suggested a favorable safety profile and meta-analytic data have reported overall complication rates comparable to those of CBA, although PV stenosis appears to occur more frequently in patients with HBA. To reduce these risks, appropriate balloon positioning and injection volume adjustments are recommended [47,48].

Despite advances in these thermal techniques, the risk of collateral damage to surrounding structures, such as the esophagus, PN, and coronary arteries, remains a critical limitation. This has led to an increased interest in non-thermal modalities, such as pulsed field ablation (PFA), which offer greater tissue selectivity and a favorable safety profile.

This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of PFA, a rapidly emerging technique in the catheter-based treatment of AF, summarizing its mechanisms, clinical applications, and future perspectives.

BIOPHYSICS OF PFA

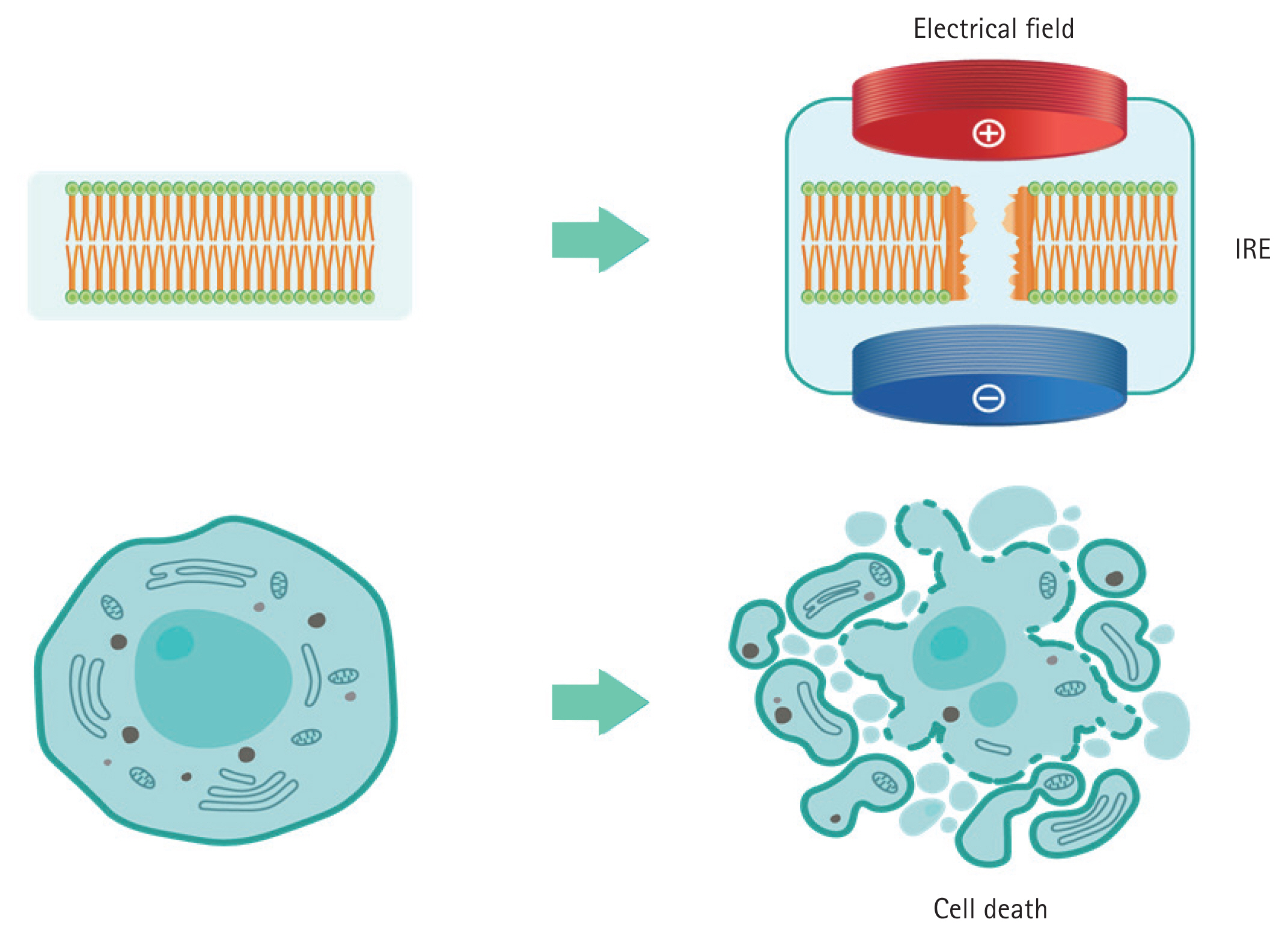

PFA is a catheter-based ablation technique that induces electroporation by applying high-voltage or high-current pulses to the electrodes to enhance cell membrane permeability. This concept was first reported by Scheinman et al. [49] in 1982 when the high-energy direct current (DC) shock was used to treat atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. Compared with early DC ablation techniques, which used a higher current density, modern PFA significantly reduces the risks of arcing and barotrauma, thereby improving procedural safety. Figure 1 illustrates the electroporation process and how high-voltage pulses lead to membrane pore formation and subsequent cellular disruption. Molecular dynamics simulations have suggested that local electric field gradients at the water-lipid interface play a crucial role in pore formation, ultimately leading to membrane disruption and apoptosis. Various tissues have different necrosis thresholds in response to PFA, with the myocardial tissue being the most sensitive because of its lower threshold. Consequently, compared with other energy sources, PFA has the advantage of minimizing collateral damage, including esophageal and nerve injuries, when ablating myocardial tissue. Unlike conventional thermal ablation, which destroys tissue through heat, PFA selectively targets myocardial cells while sparing the surrounding structures such as the esophagus, PN, and PVs [50–52].

Schematic representation of the mechanism of PFA. PFA induces IRE by applying an electrical field across the cell membrane, resulting in the disruption of cellular structures and leading to cell death. PFA, pulsed field ablation; IRE, irreversible electroporation.

The extent and selectivity of electroporation-induced tissue injury depend on several parameters, including pulse amplitude (typically 1,000–2,000 V), duration (ranging from microseconds to milliseconds), and number of pulses per application. Waveform characteristics are also critical; monophasic waveforms can induce stronger electroporation but are associated with greater skeletal muscle contraction and patient discomfort, whereas biphasic waveforms alternate polarity to minimize neuromuscular stimulation while maintaining ablation efficacy. Most current PFA systems employ biphasic or bipolar configurations to improve safety and precision. In the bipolar mode, current flows between adjacent catheter electrodes, producing localized lesions with a reduced risk to distant structures. In contrast, unipolar modes deliver current between the catheter and the external ground, potentially enabling deeper lesion formation, but with a higher off-target risk. Although energy settings are typically fixed by manufacturers, they are optimized to balance lesion durability with safety, especially to minimize coronary spasms, PN injury, or esophageal damage.

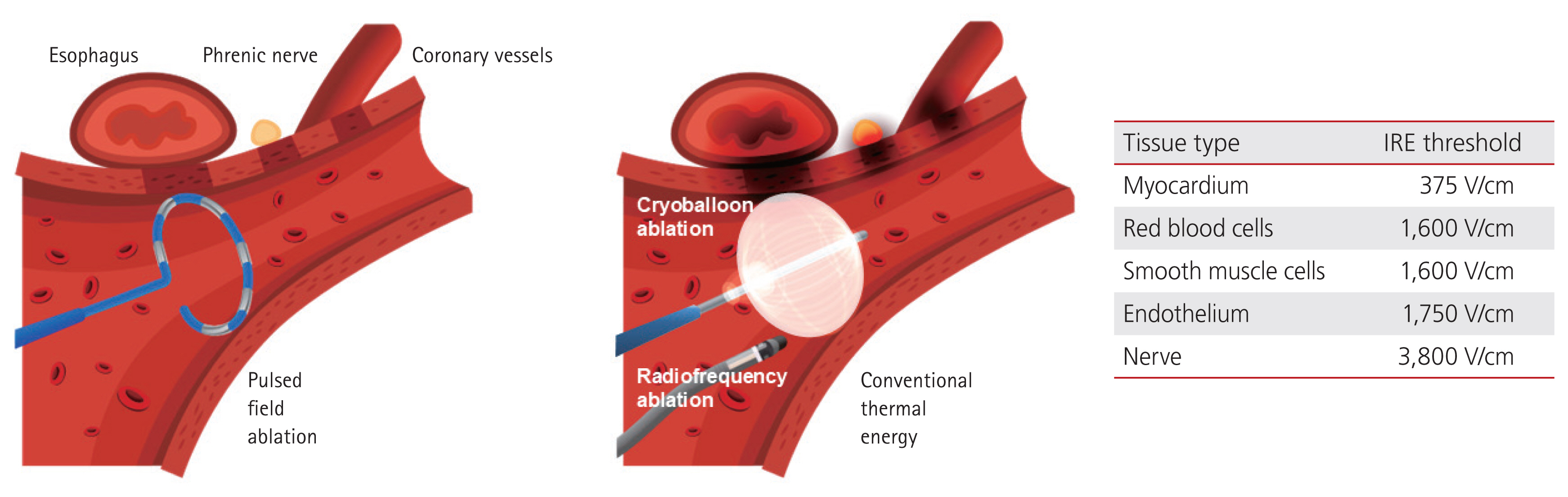

Depending on the intensity of the applied electric field, electroporation can be reversible or irreversible. The induced field causes a charge redistribution across the cell membrane, leading to the formation of microscopic pores, disrupting the cellular homeostasis, and allowing ions such as Na+, K+, and Ca2+ to flow in and out. This process results in adenosine triphosphate depletion, proteolysis, and calcium overload, ultimately leading to irreversible cell death. Additionally, owing to its tissue selectivity for irreversible electroporation (IRE) and rapid energy delivery, PFA is expected to have a relatively shorter procedure time [53,54]. Although PFA is generally regarded as a non-thermal ablation modality, some degree of localized heating may still occur depending on the interaction between the electric field intensity and current density, necessitating careful energy modulation during the procedure. Due to the differences in IRE thresholds among various tissues, PFA is known to cause less collateral damage than conventional thermal ablation [55]. Figure 2 illustrates the tissue selectivity of PFA, highlighting its lower risk of collateral injury compared to thermal energy modalities.

Comparison of collateral damage between PFA and conventional thermal ablation. PFA is characterized by tissue selectivity owing to differences in IRE thresholds among various cell types. This selectivity allows PFA to minimize collateral damage to surrounding structures such as the esophagus, phrenic nerve, and coronary vessels, thus enhancing its safety profile. PFA, pulsed field ablation; IRE, irreversible electroporation.

PRECLINICAL STUDIES ON PFA

A diverse array of preclinical studies have established the fundamental safety and effectiveness of PFA. In vitro models have confirmed the electroporation mechanism, with cardiomyocytes demonstrating greater susceptibility to electric fields than other cell types including fibroblasts and neurons [56–58].

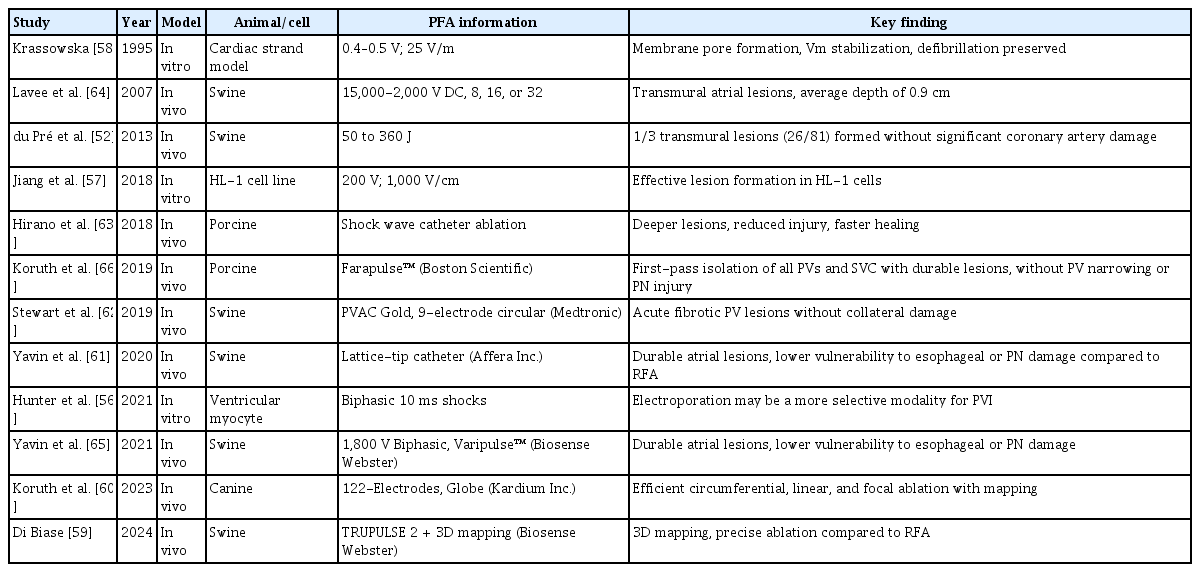

In vivo animal studies, primarily using porcine and canine models, have consistently shown that PFA can produce transmural, durable lesions with minimal or no injury to surrounding structures, such as the esophagus, PN, and coronary arteries [59–64]. Several investigations have demonstrated that lesion characteristics are influenced by the pulse amplitude, duration, catheter design, and electrode configuration. Notably, lattice-tip and circular catheters have shown high transmurality and anatomical precision while maintaining tissue selectivity [59,61,65]. Additionally, high-resolution mapping integration has been successfully applied in models using advanced platforms such as the TRUPULSE 2 and Kardium Globe™ systems [59,60]. Collectively, these studies support the translational value of PFA by confirming its non-thermal, tissue-selective lesion formation across a range of cardiac substrates. In a preclinical study using the Farawave™ (Boston Scientific) system, PFA achieved a firstpass isolation of all targeted PVs and the superior vena cava with significantly less skeletal muscle engagement, higher lesion durability than RFA, and complete preservation of PN function without evidence of PV narrowing [66]. PFA using the PVAC Gold™ (Medtronic, 9-electrode circular catheter) produced acute fibrotic PV lesions without collateral damage [62]. The Sphere-9™ (Affera Inc., lattice-tip catheter), in a swine model, demonstrated durable lesion formation with a lower vulnerability to esophageal and PN injury compared with RFA [61]. In a swine study, the VARIPULSE™ (Biosense Webster) catheter achieved transmural and contiguous lesions while maintaining a favorable safety profile with respect to collateral structures [65]. Furthermore, application of the TRUPULSE 2™ (Biosense Webster) in conjunction with a 3D mapping system demonstrated precise lesion placement comparable to that of RFA [59]. Table 1 provides an overview of preclinical studies on PFA.

CLINICAL EXPERIENCE WITH PFA

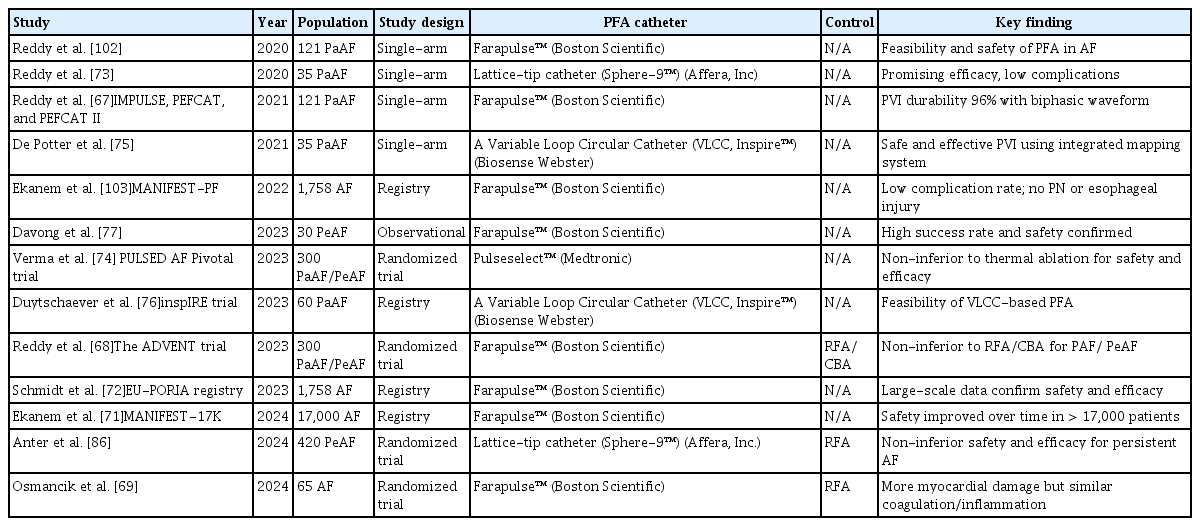

Table 2 summarizes the clinical experience with PFA. Several single-arm studies have provided evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of PFA. The IMPULSE, PEFCAT, and PEFCAT II trials, involving 121 patients with symptomatic paroxysmal AF (PAF) treated with the Farapulse™ system (Boston Scientific), demonstrated a high PVI durability (96%) using an optimized biphasic waveform [67]. More recently, randomized controlled trials have validated the clinical utility of PFA. The Pulsed Field or Conventional Thermal Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation (ADVENT) trial compared FARAWAVE™-based PFA with conventional thermal ablation in patients with PAF and demonstrated non-inferiority in terms of both efficacy and safety at one year [68]. Another study comparing FARAWAVE™-based PFA and RFA found that, although PFA induced approximately 10 times more myocardial damage, no significant differences were noted in platelet activation, coagulation, or inflammatory responses [69]. Recently, the Pulsed-Field or Cryoballoon Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation (SINGLE-SHOT-CHAMPION) trial compared PFA and CBA in patients with symptomatic PAF and demonstrated the non-inferiority of PFA in terms of efficacy [70]. In addition to clinical trials, real-world registry data have reinforced the favorable profile of PFA. The MANIFEST-17K and EU-PORIA registries, both evaluating the FARAWAVE™ system, reported lower rates of collateral damage and efficacy comparable to that of conventional thermal ablation [71,72].

A first-in-human study of the lattice-tip ablation catheter (Sphere-9™) showed a promising efficacy with a low complication rate [73]. The Dual-energy lattice-tip ablation system for PeAF: a randomized trial (SPHERE PER-AF) assessed a dual-energy lattice-tip system (Sphere-9™) for persistent AF and showed a comparable safety and effectiveness to RFA [71]. The PULSED AF Pivotal Trial, a single-arm study utilizing the PulseSelect™ system (Medtronic), reported a low primary safety event rate (0.7%) and effectiveness comparable to conventional ablation modalities [74]. The integration of a variable loop circular catheter (VLCC, Varipulse™, Biosense Webster) with a 3D mapping system has demonstrated the safety and efficacy of PFA for PVI in patients with PAF [75,76].

PFA CATHETERS: CURRENT DESIGNS

PFA catheters currently in clinical use are primarily designed for atrial arrhythmia treatment and can be broadly classified into two categories: (1) circumferential ablation catheters and (2) focal point-by-point ablation catheters.

Circumferential ablation catheters

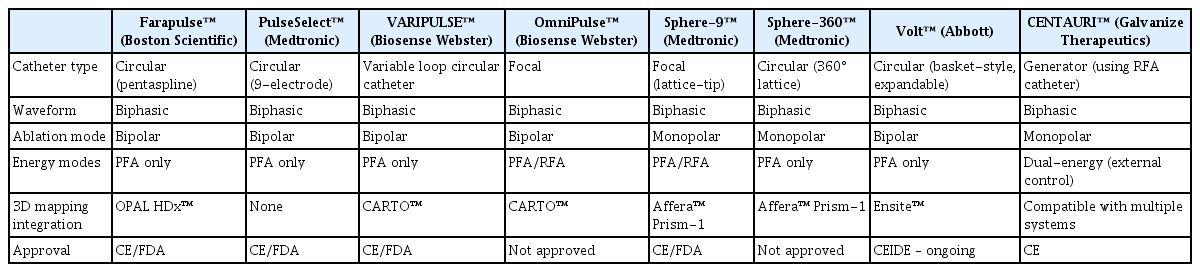

These catheters are typically used for a single-shot PVI. The Farapulse™ system consists of pentasplines carrying 20 electrodes, which can be changed from a so-called flower to a basket and even an olive configuration. This ablation device has been most widely used, and the contemporary 3D mapping system (Ensite™, Abbott) provides impedance-based catheter visualization. PulseSelect™ and VARIPULSE™ have evolved from the former circular RFA platform. Recently, the Volt™ PFA System (Abbott) was fully integrated into a dedicated 3D mapping system (Ensite™) and was CE-approved [71].

Focal point-by-point ablation catheters

These systems include Affera Sphere-9™ (Medtronic), OmniPulse™ (Biosense Webster), and the CENTAURI system (Galvanize Therapeutics), which delivers PFA through conventional radiofrequency (RF) catheters. These platforms are designed for greater flexibility in lesion creation, particularly for complex arrhythmia substrates and are increasingly being investigated for broader clinical indications beyond PAF. Notably, the Affera Sphere-9 and OmniPulse support dual-energy delivery using both RF and PFA, allowing operators to switch energy sources within a single-catheter platform system without the need for catheter exchange. This flexibility not only facilitates lesion customization and minimizes collateral injury but also improves workflow efficiency by reducing procedure time and fluoroscopy exposure. The key features of currently available PFA catheter systems, including energy modality, polarity, and mapping system compatibility, are summarized in Table 3.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES IN PFA

Integration with 3D mapping

The integration of PFA catheters with the available 3D mapping systems may allow for more precise PFA. So far, AFFERA™, Varipulse™, and very recently the Volt™ PFA System have been offering 3D mapping capabilities. The Farapulse™ catheter integration into a specific 3D mapping system is expected to be available soon. These 3D mapping-integrated PFA systems enable electrophysiologists to perform zero- or minimal-fluoroscopic procedures and facilitate tailored ablation strategies based on anatomical and electrophysiological data. Importantly, this integration opens the door to expanding PFA applications beyond PVI to substrate-guided ablation, including linear ablation and complex arrhythmia modifications. As shown in Table 3, several catheter platforms have already achieved or are actively pursuing full integration with commercial mapping systems such as CARTO™ or Ensite™, supporting the evolution toward precision-guided PFA.

Expanding applications to complex arrhythmias

As clinical experience accumulates, PFA catheter technology continues to evolve to meet the needs of complex arrhythmia ablations. Although most current applications focus on PVI of PAF, ongoing developments are targeting PeAF, linear lesions, and even ventricular tachycardia ablation. The tissue-selective nature of PFA holds promise for safer and more effective lesion creation, even in anatomically challenging regions, such as the mitral isthmus or ventricular scar tissue. Although current PFA catheters are primarily designed for single-shot PVI, expanding their application to linear ablation has gained attention, particularly in PeAF. Recent reports have described various strategies, including the use of the FARAPULSE catheter in a flower configuration to create extensive lesions along the mitral isthmus [77], a dual-mode lattice-tip catheter toggling RF/PFA energy for targeted linear ablation [78], and reshaping the pulseselect circular catheter into a linear form to achieve cavotricuspid isthmus (CTI) ablation [79]. However, clinical application of linear PFA remains challenging. Coronary artery spasm, especially involving the right coronary artery during CTI ablation, has been reported, and lesion durability in thicker regions such as the mitral isthmus remains uncertain owing to limited long-term data. Additionally, lesion formation using the flower configuration may result in broader than necessary tissue damage, which could lead to excessive ablation, although further validation is required.

SAFETY AND EFFICACY PROFILE OF PFA COMPARED TO CONVENTIONAL THERMAL ABLATION

PN injury

PN injury is a recognized complication of AF ablation, particularly CBA [80]. In contrast, PFA has shown a markedly lower incidence of PN injury owing to its tissue selectivity. Preclinical studies have reported only transient PN palsy without histologic damage [51,61,66,81]. In the ADVENT trial, no PN injuries were observed in PFA-treated patients, whereas two cases (0.7%) occurred in the thermal ablation group [68]. Real-world data from the MANIFEST-PF and MANIFEST-17K registries also confirmed a low incidence of PN injury, with no persistent cases reported in more than 17,000 patients [71,82]. Although isolated case reports have described transient dysfunction, these findings do not contradict PFA’s favorable safety profile of PFAs [83,84]. Nonetheless, caution should be exercised when ablating the right superior PV.

Esophageal injury

PFA’s nonthermal, tissue-selective mechanism of PFA is associated with a lower risk of esophageal injury than that of RFA. Preclinical and clinical studies have consistently shown no histopathological esophageal damage caused by PFA [85]. Several clinical trials have shown that PFA’s nonthermal mechanism of PFA contributes to its favorable esophageal safety profile, although long-term outcomes require further study [68,74,86]. Real-world data from large-scale registries (MANIFEST-17K and EU-PORIA) further supported the low incidence of esophageal complications associated with PFA [71,72]. However, a dose-dependent esophageal temperature elevation has been reported, highlighting the need for continued monitoring [87].

PV stenosis

PV stenosis is a serious but uncommon complication of thermal ablation, and is typically associated with excessive lesion depth or overlapping energy applications. PFA’s non-thermal mechanism of PFA significantly reduces the risk of PV stenosis. Preclinical and clinical studies, including a sub-analysis of the ADVENT trial, have shown no significant PV narrowing compared to thermal techniques, reinforcing its anatomical safety [88–90].

Microbubble formation and silent cerebral lesions

PFA induces electrolysis and gas formation, resulting in microbubble generation [91]. Although symptomatic thromboembolic events are rare (< 1%), silent cerebral lesions were observed in up to 18.5% of the patients in the selected studies [74,92,93]. Most patients are asymptomatic and the symptoms resolve spontaneously; however, the long-term cognitive impact remains unclear. Proper sheath management is essential to prevent macro-air embolisms.

Hemolysis

PFA-related hemolysis appears to be dose-dependent, with an increased risk as the number of applications increases. While significant renal injury remains uncommon when fewer than 70 lesions are present, the risk of acute kidney injury is multifactorial, depending on the hydration status and baseline renal function [94,95]. Further studies are needed to understand the long-term impacts on renal function.

Coronary artery damage

Epicardial IRE does not cause narrowing of the coronary artery in animal studies [52,96]. However, transient coronary spasms after PFA have been reported in several animal studies [97,98]. Moreover, intracoronary PFA occasionally leads to fixed coronary lesions, and intracoronary nitroglycerin does not consistently resolve spasms in swine models [99]. Recent studies have suggested that preprocedural nitroglycerin may mitigate this effect [100,101]. Coronary artery proximity should be carefully considered during ventricular or mitral isthmus ablation.

CONCLUSION

This review provides a comprehensive overview of PFA as a novel approach for AF catheter ablation. To date, the safety profile of PFA has demonstrated significant improvements compared to those with conventional thermal ablation. However, the potential risks of complications, including hemolysis and coronary spasms, remain, and as with cryoablation, the possibility of previously unrecognized complications emerging with an increased procedural volume cannot be excluded. Nevertheless, considering the mechanism of action of PFA and its tissue selectivity, this represents a promising advancement in AF catheter ablation, offering improved safety and effective treatment options.

Notes

Acknowledgments

The research support team at the Yeungnam University College of Medicine supported the medical illustration of this study.

CRedit authorship contributions

Hong-Ju Kim: conceptualization, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing; Chan-Hee Lee: conceptualization, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None