From bench to bedside: pancreatic juice as a platform for biomarker discovery in pancreatic disease

Article information

Abstract

Pancreatic juice (PJ) analysis has emerged as a promising modality for the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases, particularly pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis. This review explores the role of PJ analysis in identifying biomarkers for the early detection and differentiation of pancreatic diseases. PJ, which is rich in pancreatic enzymes and exfoliated cellular material, can be collected endoscopically and is often stimulated by intravenous secretin to enhance its yield. Cytological, proteomic, and genomic analyses of PJ demonstrate its potential in the early detection and differential diagnosis of pancreatic pathologies. The integration of protein-based and genetic markers offers improved sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. However, several challenges persist, including the need for standardized protocols for PJ collection, processing, and analysis. Despite these limitations, PJ analysis represents a valuable adjunct diagnostic approach that warrants further investigation and clinical validation.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic juice (PJ) is an enzyme-rich fluid secreted by the pancreatic exocrine glands into the duodenum. Currently, PJ aspiration and enzyme analysis are clinically indicated for evaluating pancreatic exocrine insufficiency (PEI) [1]. Owing to its proximity to the pancreatic parenchyma, PJ is a promising source for biomarker discovery in pancreatic pathology. It contains cellular material shed from the pancreatic ductal epithelium and provides insight into the underlying genomic, proteomic, and cytological alterations associated with pancreatic diseases. PJ has been extensively studied as a potential diagnostic tool for malignant and premalignant pancreatic diseases. In this review, we explore the current promises, challenges, and advancements of PJ as a biomarker for the early detection and characterization of pancreatic diseases.

PJ COLLECTION AND STORAGE

PJ can be collected from the duodenum or directly from the pancreatic duct, with or without intravenous (IV) secretin stimulation (typically 0.2 μg/kg body weight). In clinical practice, PJ collection is primarily performed as part of the direct pancreatic function test (PFT) to evaluate PEI. The PJ may be collected from the duodenum via a fluoroscopically guided oro-duodenal tube called a Dreiling tube (traditional direct PFT) or suctioned through the working channel of an endoscope placed into the duodenum (endoscopic test) [2]. PFT involves quantification of bicarbonate levels after secretin stimulation or lipase levels after cholecystokinin stimulation to assess exocrine function. The secretin stimulation test has become the predominant method for estimating exocrine pancreatic function. The key parameters include the peak bicarbonate concentration, bicarbonate output, and total fluid volume measured during the test. A peak bicarbonate concentration of < 80 mEq/L is considered diagnostic of PEI [3]. The endoscopic method has largely replaced the traditional Dreiling tube method due to its safety, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness [4]. Although PFT is sensitive for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis (CP), it is usually not required in patients with obvious features of CP on imaging and is only indicated for the diagnosis of early-stage CP [5]. Despite being the most sensitive test for the diagnosis of PEI, the reported sensitivity of endoscopic PFT in patients with established CP ranges from 72% to 94% [6–14]. Furthermore, these procedures are invasive, resource-intensive, and often unavailable in developing countries. Consequently, fecal elastase estimation is currently the first-line test of choice for the diagnosis of PEI, and magnetic resonance imaging-based PFT shows promise in this regard [15,16].

For research purposes, PJ aspiration from the duodenum is typically performed 10 minutes after secretin injection (0.2 μg/kg for 1 minute) [17]. The Consortium for the Study of Chronic Pancreatitis, Diabetes, and Pancreatic Cancer recommends PJ collection endoscopically by endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) within 0–20 minutes after IV secretin injection, followed by immediate centrifugation, aliquoting, and freezing to −80°C [18]. PJ is collected either from the pancreatic duct after cannulation during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), from the duodenum using EGD, or directly from the pancreatic duct during pancreatic surgery. Sadakari et al. [19] and Yu et al. [20] demonstrated that secretin-stimulated PJ collected from the duodenum could identify pancreatic mutations at low concentrations, despite DNA contamination from the duodenal lumen. Most studies use endoscopic aspiration of duodenal fluid (DF) via the suction channel of the endoscope, which appears to be superior for biomarker detection compared to catheter aspiration through the accessory channel [21]. The use of a distal endoscopic cap positioned near the major papilla increases the yield of PJ-derived DNA [22]. Mori et al. [23] demonstrated that DF collected prior to secretin stimulation may yield adequate amounts of protein for analysis. Endoscopic nasopancreatic drainage has also been used to collect PJ for the cytological diagnosis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) in patients without visible tumors on EUS [24].

PJ contains numerous digestive enzymes that pose a risk to the integrity of clinically relevant proteins, DNA, and RNA, even when immediately frozen. To address this issue, protease inhibitors are typically added at the time of sample collection to prevent proteolysis. In a proteomic study, the addition of inhibitors such as phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), aprotinin, and complete protease inhibitors improved the resolution of 2D gel electrophoresis; however, mass spectrometry was not performed to confirm the prevention of degradation [25]. Another study examined the impact of preservation methods and storage time of PJ on the integrity of proteins and nucleic acids. Patients who underwent PFT had the PJ frozen to −80°C at various intervals after collection (immediately, after 1 hour, 2 hours, 4 hours, and overnight on ice), with or without RNase and protease inhibitors. The proteins remained stable for up to 4 hours on ice, whereas DNA degradation began after 2 hours of incubation. RNA degraded rapidly unless it was snap-frozen. The addition of inhibitors delayed degradation but did not fully prevent it. They also found that the ion and enzyme concentrations in the pancreatic fluid aspirated at different intervals after secretin injection (0–10 minutes and 10–20 minutes) showed no significant differences [26].

PROTEIN BIOMARKERS IN PJ

Proteins are products of the functional endpoint of gene expression and offer a real-time snapshot of cellular physiology. In pancreatic diseases, particularly PDAC, differential protein expression has been observed at various stages of cancer development and progression, supporting its utility as a biomarker for early detection and diagnosis [27].

Several research groups have employed discovery proteomics to identify proteins overexpressed in PJ obtained from patients with PDAC, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), and CP. In a quantitative proteomics study comparing PJ from patients with PDAC with that from patients with normal pancreas, 44 proteins were exclusively observed in the PDAC group, including 15 proteins overexpressed by at least two-fold in PDAC, including insulin growth factor binding protein 2 [28]. Pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor levels were significantly elevated in IPMN compared to those in PDAC and CP, with a sensitivity of 48% and specificity of 98% [29].

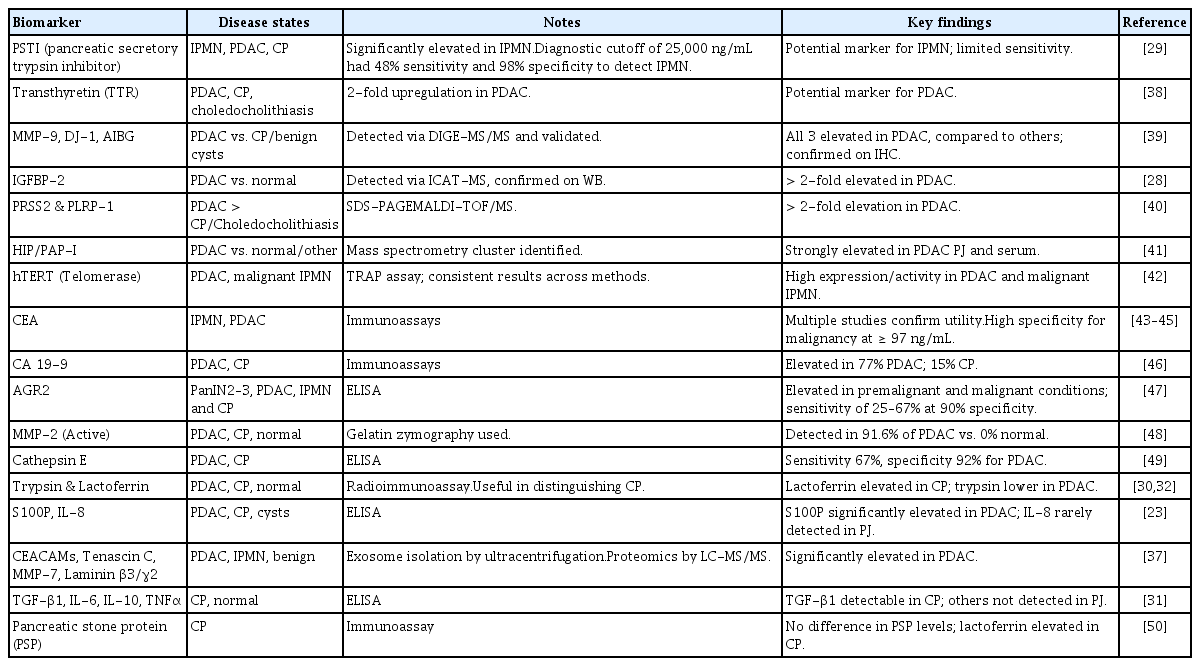

PJ proteomics has also been explored to differentiate patients with CP from those with PDAC and healthy controls. In a study involving 44 patients undergoing ERCP (24 with CP, 10 with PDAC, and 10 with normal pancreas), PJ lactoferrin levels were significantly higher in patients with CP than in those with PDAC and in controls, whereas PJ trypsin levels were lower in the PDAC group [30]. In a study looking at cytokine analysis in the PJ, TGF-β was seen in 85% of patients with CP compared to 17% of patients with a normal pancreas [31]. Albumin in the PJ has been shown to be elevated in patients with CP and lower in patients with PDAC [32,33]. The other markers identified using discovery proteomics are summarized in Table 1.

An area of increased research interest is extracellular vesicles (EV), which are secreted by most cells and have been observed in the PJ. Proteomic analysis of EVs in the PJ of patients with CP and PDAC has identified unique proteins [34]. In a recent study, size-exclusion chromatography was found to be the most effective method for isolating EVs from the PJ [35]. Nesteruk et al. [36] demonstrated that while the overall concentration of EVs did not significantly differ between patients with PDAC and controls, a higher number of larger EVs were identified in the PJ but not in the serum of patients with PDAC. Zheng et al. [37] reported multiple unique proteins in PJ-derived exosomes from patients with PDAC compared to those in controls, suggesting the potential utility of exosomal proteomics for biomarker discovery. These findings support the potential use of PJ as a valuable diagnostic fluid, particularly for PDAC, IPMN, and CP diagnosis. In addition to the markers discussed above, numerous other proteins identified in pancreatic juice have been associated with pancreatic neoplasia (Table 1). These include digestive enzymes, inflammatory mediators, extracellular matrix–related proteins, and tumor-associated antigens such as lactoferrin, matrix metalloproteinases, AGR2, transthyretin, and carcinoembryonic antigen [38–50].

GENETIC MARKERS IN PJ

Progressive genetic alterations occur in the pancreas before it evolves into frank malignancy or even before the production of abnormal proteins. Genetic alterations in the PJ have been evaluated to aid in the identification of malignant lesions and stratification of patients with high-grade premalignant lesions. KRAS mutations are the most prevalent, occurring in 90.1% of PDAC precursor lesions [51]. GNAS mutations have also been reported in IPMN with low-grade dysplasia [52,53]. The emergence of TP53 and SMAD4 mutations correlates with high-grade dysplastic and malignant pancreatic lesions [54,55]. A meta-analysis performed by Visser et al. [56] showed that TP53 had the highest pooled sensitivity of 42% and specificity of 98%, with a diagnostic odds ratio of 36 for the presence of high-grade dysplasia or pancreatic cancer.

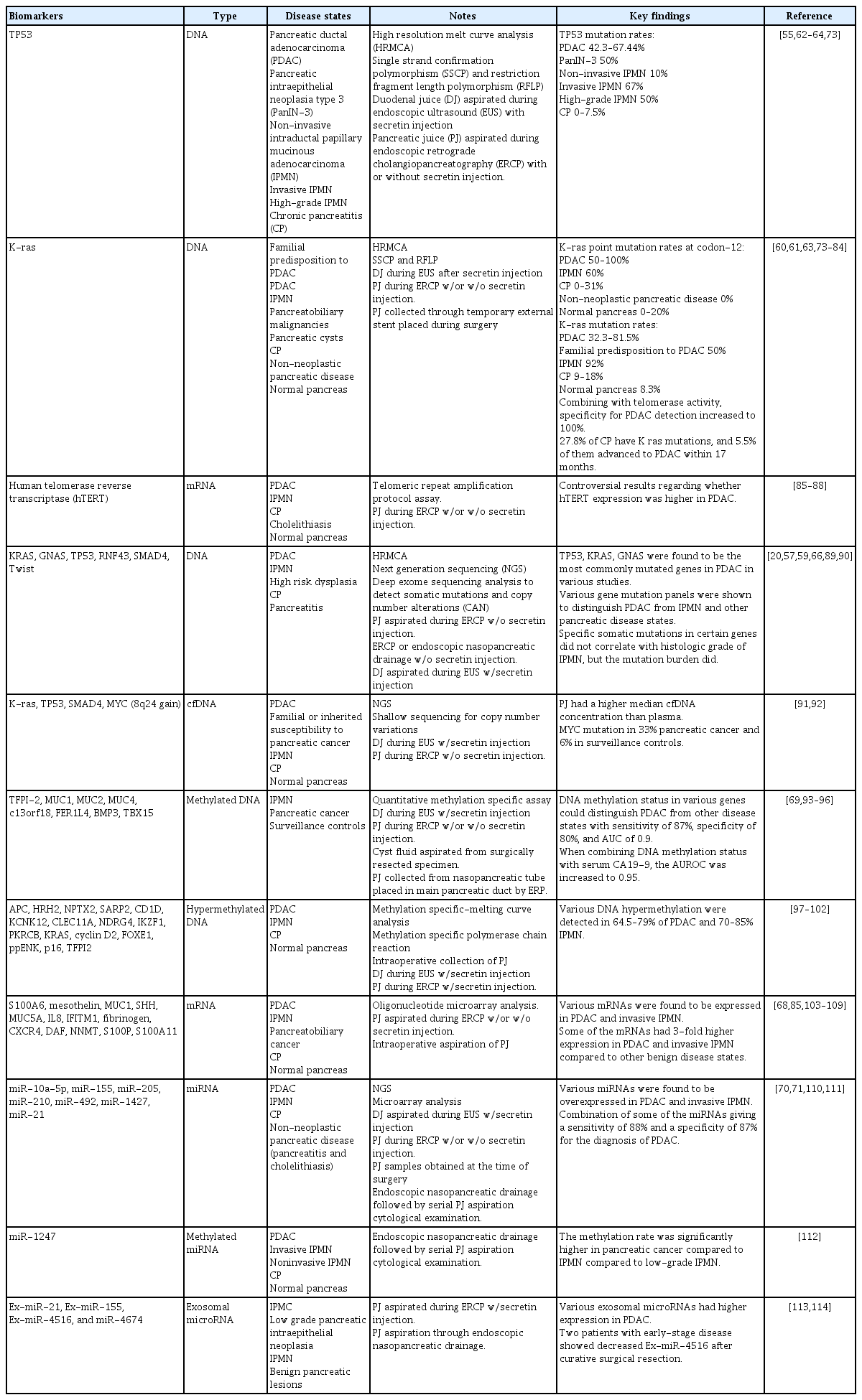

DNA mutations, mRNA and miRNA expression profiles, and methylated DNA markers have been detected in PJ across various pancreatic diseases using various analytical techniques.

Methods employed to detect mutations in PJ have evolved from older methods, such as restriction fragment length polymorphism, to more advanced next-generation sequencing (NGS). DNA mutations in the PJ are significantly higher in PDAC and high-grade dysplasia than in the normal pancreas [20,57]. More than 1% of PJ DNA in the PJ was mutated in 53% of patients with PDAC, compared to only 11% of patients without PDAC [58]. Patients at high risk for PDAC have also been shown to have a higher burden of mutations without any imaging evidence of a lesion, likely reflecting the increasing incidence of subclinical pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN).

Mutations in KRAS and GNAS have been the focus of multiple studies, although the findings have varied. In a study using NGS of PJ obtained via ERCP, KRAS mutations were present in 88% of IPMN cases [59]. In DF samples, KRAS mutations were observed in 91.2% of patients with PDAC, 91.1% of patients with IPMN, and 41.7% of patients with a normal pancreas [20]. The prevalence of KRAS mutations in patients with DF and a family history or genetic predisposition to PDAC is 50% [60]. KRAS codon 12 mutations were observed in 50–100% of PDAC, 0–18% of CP, and 0–20% of normal pancreatic cases (Table 2). There was little concordance between the KRAS mutations observed in the PJ and resected PDAC tissue, suggesting that they may have originated from PanINs located elsewhere in the pancreas.

The combination of TP53 and KRAS mutations in PJ increases the specificity of PDAC [61]. TP53 mutations have been identified in 42.3% of ERCP-derived PJ and 67.44% of DF in patients with PDAC [54,62,63]. In DF samples, TP53 mutations were present in 50% of patients with high-grade IPMN [54]. Another study showed that DF TP53 and/or SMAD4 mutation concentrations were significantly higher in PDAC than in normal pancreas. A higher mutation score (≥ 5) of TP53 with or without SMAD4 mutation differentiated PDAC from IPMN with 100% specificity [20]. Suenaga et al. [57] demonstrated that high overall mutation concentrations in PJ, assessed using digital NGS targeting a 12-gene panel, identified PDAC or high-grade dysplasia in resected specimens with 72% sensitivity and 89% specificity. SMAD4/TP53 mutations with high scores (mutation score of ≥ 5) could distinguish pancreatic lesions with high-grade dysplasia and/or cancer with a sensitivity and specificity of 61% and 96%, respectively (area under the curve [AUC] of 0.8). Malignant IPMN and IPMN with concomitant PDAC are more likely to be associated with TP53 mutations in the PJ [59,64]. Other studies have confirmed the specificity of SMAD4 mutations for PDAC and advanced pancreatic lesions [20,57].

GNAS mutations in PJ aspirated from the duodenum were observed in 64.1% of patients with IPMN and 45.5% of patients with pancreatic cysts < 5 mm [65]. In ERCP-derived PJ, GNAS and RNF43 mutations were observed in 76% and 30% of patients with IPMN, respectively [59]. Although KRAS, GNAS, TP53, and RNF43 mutations do not correlate with the histological grade of IPMN, the mutational burden is higher in high-grade lesions [66]. In a retrospective study by Simpson et al. [67], patients with a family history of pancreatic cancer/genetic syndrome, presumed IPMN, cysts, presumed pancreatitis, or a normal pancreas underwent genetic analysis for secretin-induced DF. Some patients underwent concomitant EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUSFNA) of the pancreatic cyst or main duct fluid aspiration. The yields of KRAS (3% vs. 42.3%) and GNAS (3.2% vs. 8.7%) were lower in the DF of sporadic IPMN than in EUS-FNA specimens. This suggests that although IPMNs are duct-connected, they may not shed sufficient genetic material into the PJ for sensitive detection, making FNA the preferred method for biomarker development in cystic lesions.

The RNA expression of multiple candidate genes has been investigated to detect and differentiate between malignant and premalignant pancreatic diseases. Mesothelin, sonic hedgehog, MUC1, MUC5A, and hTERT were some of the genes found to be overexpressed in PDAC compared to controls (Table 2) [26]. However, a study by Oliveira-Cunha et al. [68] using microarray analysis of PJ and surgical specimens found no significant differences in RNA expression between benign and malignant pancreatic lesions, likely due to the suboptimal RNA quality in PJ.

DNA methylation is an epigenetic mechanism involved in the regulation of gene transcription. Aberrant methylation patterns in the PJ are potential diagnostic markers for both PDAC and IPMN. Majumder et al. [69] identified a panel of three methylated DNA markers (C13orf18, FER1L4, and BMP3) in DF obtained after secretin injection to reliably distinguish PDAC and high-grade dysplasia from non-diseased controls, with an area under the receiver operator curve of 0.9. A meta-analysis showed that NPTX2 performed best for diagnosing pancreatic cancer, with a sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 100% [43]. Other DNA markers methylated at various genetic loci were also reported to be associated with PDAC (Table 2).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs involved in gene regulation and are promising biomarkers. Several miRNAs, such as miR-205, miR-210, miR-492, miR-1427, miR-21, and miR-155, are overexpressed in the PJ of patients with PDAC (Table 2). The miR-10a-5p levels were significantly elevated in the PJ from invasive IPMN compared to noninvasive IPMN [70]. In addition, miR-155 levels are elevated in the PJ of patients with IPMN compared to those of controls [71]. Additionally, the expression levels of miR-21, miR-25, and miR-16 were higher in PDAC than in non-malignant controls. The combination of these PJ miRNAs with serum miR-210 and CA19-9 achieved an AUC of 0.91, with 84.2% specificity and 81.5% sensitivity for PDAC detection [72].

Several additional studies have investigated a broad range of genetic alterations in pancreatic juice, including somatic mutations, copy number variations, and epigenetic changes; these findings are summarized in Table 2 [73–114].

CYTOLOGY

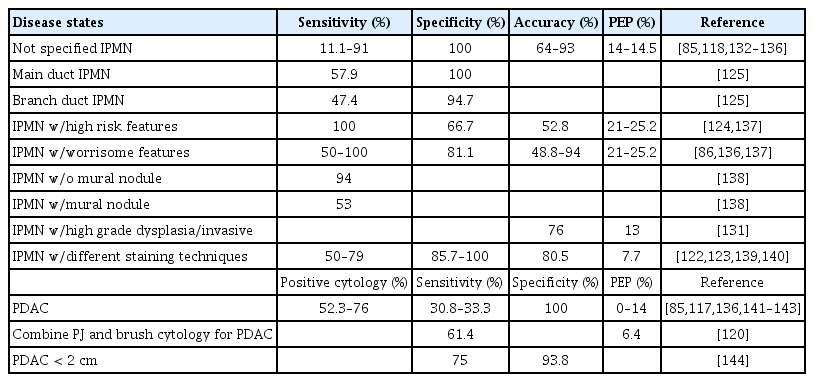

Cytological analysis of the PJ was performed to detect PDAC (Table 3). Most of these studies used PJ obtained via ERCP. Previous studies using DF have shown conflicting results regarding the cytological diagnosis of pancreatic malignancies [115,116]. In previous studies, the accuracy of PJ cytology for the diagnosis of PDAC ranged from 30% to 79% [117]. A more recent study reported sensitivities, specificities, and accuracies of 91%, 100%, and 93%, respectively [118]. Nakaizumi et al. [119] evaluated the ability of PJ cytology to identify early pancreatic cancers in 295 consecutive patients without obvious masses and identified 12 (4%) patients with abnormal cytology. Pathology revealed four adenocarcinomas with minimal invasion, three carcinomas in situ, and five with marked atypia. The sensitivity of cytology for PDAC detection increases from 21.3% to 40.9% when the PJ is aspirated after brush cytology [120].

A systematic review conducted by Tanaka et al. [121] analyzed different methodologies to identify the markers of malignant IPMN. PJ cytology had the highest AUC of 0.84, with 54% sensitivity and 94% specificity. Hibi et al. [122] found that the IPMN subtype classification of PJ agreed with histopathology in 79% of cases. Subtypes were classified based on the shape of the cell clusters and their cytoplasmic features. The sensitivity and specificity of PJ cytology to identify intestinal, gastric foveolar, oncocytic, and pancreatobiliary origins range from 72.7% to 100% and 85.7% to −93.8%, respectively. The addition of MUC stains (MUC1, MUC2, and MUC5AC) to PJ cytology has been shown to significantly improve the IPMN subtype classification from 42% to 89% (p < 0.01) [123]. The addition of PJ cytology increased the diagnostic accuracy for malignant IPMN in patients with worrisome imaging features from 33% to 49%, but did not significantly enhance the accuracy in those with high-risk features (65% to 52%) [124]. The sensitivity and specificity of PJ cytology obtained by endoscopic peroral pancreatoscopy to detect malignancy in main-duct IPMN and branchduct IPMN were 80%/100% and 42.9%/100%, respectively [125].

An endoscopic nasopancreatic drain allows recurrent PJ collection from the same patient, permitting multiple replications of cytological analysis. Mikata et al. [126] found that this method had a significantly higher sensitivity (52%), specificity (83%), and accuracy (60%) for detecting malignant IPMNs than conventional single-time PJ aspiration via ERCP. Although cytology has a good positive predictive value for identifying malignant cells in the PJ, the risks associated with ERCP, including post-ERCP pancreatitis (2.9–25.2%), limit its use purely for cytologic sampling in the absence of therapeutic indications. Nagayama et al. [127] showed that, despite its low sensitivity, cytology has a high positive predictive value. Mori et al. [128] further showed that cytology is worth considering in patients with abrupt changes in the caliber of the pancreatic duct with distal pancreatic atrophy who might otherwise be uncertain about surgery. Sagami et al. [129] demonstrated that salvage PJ cytology can diagnose 74.3% of pancreatic tumors ≤ 10 mm that failed detection using EUS-FNA. For PDAC ≤ 10 mm, ERCP-based cytology had 92.3% sensitivity compared to 33.3% for EUS-FNA [130]. Liquid-based cytology (LBC) is a technique in which cell samples are processed into a uniform layer, thereby reducing artifacts and improving cellular preservation. LBC has been shown to increase the accuracy of PJ cytology in detecting malignant IPMN from 56% to 76% compared with that of conventional cytology [131].

Table 3 summarizes the available literature evaluating the use of pancreatic juice cytology and adjunctive cytologic markers for the detection of various pancreatic neoplasms, highlighting their diagnostic performance across a range of benign, premalignant, and malignant entities [132–144].

DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Although PJ is a promising source for biomarker evaluation, the heterogeneity of existing studies limits meaningful comparisons and broad clinical applicability. A major limitation of the current literature on biomarker analysis of the PJ is the lack of standardized protocols (SOPs) for specimen collection, processing, storage, and analysis. Variability in techniques, such as differences in the timing of collection, use (or lack thereof) of preservative agents, and handling of specimens, contribute to inconsistent specimen quality and results. This methodological heterogeneity hampers cross-study comparisons and limits the reproducibility and generalizability of findings. The previously released SOP for specimen collection, processing, and storage provides no recommendation for the use of preservative chemicals to prevent specimen degradation [18]. However, based on other studies, the use of protease inhibitors, such as PMSF, aprotinin, and complete protease inhibitors, should be standard practice to preserve the integrity of proteins, RNA, and DNA [25,26]. Therefore, more sensitive and specific methods for detecting and quantifying biomarkers in PJ should be developed.

The clinical utility of PJ biomarkers requires validation in large, multicenter studies. In particular, the cytological assessment of DF for detecting pancreatic malignancies or high-grade dysplasia must be confirmed in broader populations. Currently, no clinical guidelines or consensus statements support the routine use of PJ for the diagnosis or risk stratification of premalignant or malignant pancreatic diseases. Furthermore, the discovery of novel biomarkers in the PJ for diagnosing minimal changes in CP, where imaging findings are often subtle, remains a critical unmet need. Future PJ biomarker research is likely to involve integrative diagnostics combining multiple molecular data layers, including overexpressed proteins, mutant DNA, methylation signatures, miRNAs, and serum biomarkers, into a unified analytical framework. Advanced machine learning algorithms can be employed to utilize PJ biomarkers along with clinical, imaging, and endoscopic data to generate composite risk scores. This approach potentially improves diagnostic accuracy, facilitates early detection, and supports personalized risk stratification in patients at risk of pancreatic cancer.

In conclusion, PJ offers unique insights into the local biochemical and molecular milieu of the pancreas. It holds considerable promise as a biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of benign, premalignant, and malignant pancreatic lesions based on cytological, genetic, epigenetic, and proteomic analyses of the lesions. PJ analysis in patients with malignant and premalignant pancreatic conditions offers an opportunity for early intervention and personalized treatment, potentially improving patient outcomes in the future. There is a critical need for large-scale multicenter studies to validate promising biomarkers and establish standardized, reproducible methods to ensure test accuracy and comparability across different studies.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Pradeep K. Siddappa: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft; Niwen Kong: data curation, formal analysis, writing - review & editing; Alice Lee: formal analysis, writing - review & editing; Yi Jiang: formal analysis, writing - review & editing; Walter G. Park: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, validation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None