Advanced strategies for the management of patients with diabetic foot ulcers: a comprehensive review

Article information

Abstract

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are among the most serious and common complications of diabetes mellitus. They significantly affect patients’ quality of life and impose a substantial economic burden on healthcare systems worldwide. In Korea, the prevalence of diabetes and related complications, such as DFUs, has been increasing, reflecting a broader global trend. DFUs are associated with severe complications, including infections, neuropathy, and peripheral arterial disease, often leading to amputation. In Korea, diabetic foot complications are a major cause of non-traumatic lower-extremity amputations, with high mortality rates following amputation. DFUs also significantly reduce patients’ quality of life and increase healthcare costs. The management of DFUs requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates medical, surgical, and advanced therapeutic interventions to prevent severe outcomes, such as amputation. This comprehensive review of DFU management in patients with diabetes was developed in collaboration with the Diabetic Study Group of the Korean Diabetes Association and Korean Society for Diabetic Foot. This review examines the epidemiology, clinical significance, diagnosis, and evidence-based treatment of DFUs.

INTRODUCTION

Diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) are a serious and common complication of diabetes mellitus, affecting approximately 19–34% of patients during their lifetime [1]. DFUs are associated with a markedly increased risk of infection, lower-limb amputation, and mortality. The global burden of DFUs continues to rise, driven by the increasing prevalence of diabetes, limited public awareness, and gaps in timely diagnosis and multidisciplinary management.

The pathogenesis of DFUs is multifactorial and typically involves diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), peripheral arterial disease (PAD), and biomechanical abnormalities. These interrelated mechanisms not only contribute to ulcer formation but also impair wound healing, increase the risk of infection, and significantly contribute to ulcer recurrence.

Despite advances in preventive and therapeutic modalities, the management of DFUs remains a clinical challenge because of their multifactorial etiology and the need for complex decision-making and interdisciplinary collaboration. Achieving optimal outcomes requires timely diagnosis, accurate risk stratification, and coordinated implementation of multidisciplinary interventions, including systemic metabolic regulation, local wound management, and vascular or surgical treatments.

This review summarizes the current evidence on DFUs, with a focus on their epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnostic strategies, and management principles. It also provides an evidence-based perspective to inform clinical decision-making and outlines current approaches and challenges in DFU management.

ETIOLOGY AND CHARACTERISTICS

Etiology and risk factors of DFUs

DFUs are primarily caused by repetitive minor trauma to high-risk or pre-ulcerative areas of the foot [2]. Pressure on weight-bearing sites, friction from ill-fitting shoes, and abnormal gait can result in unnoticed injuries that progress to ulceration. The pathogenesis is multifactorial and is categorized as neuropathic (35%), ischemic, or mixed neuroischemic (50%) [3]. DPN impairs protective sensation, increases susceptibility to minor trauma, and allows pre-ulcerative lesions to go unnoticed and untreated [2]. Typical neuropathic ulcers appear as punched-out lesions with thick calluses and elevated borders in weight-bearing areas. By contrast, PAD reduces blood flow, resulting in ischemic and neuroischemic ulcers [4]. These ulcers often present with pale or necrotic bases and may progress to gangrene at friction sites, such as the first metatarsophalangeal joint.

Multiple clinical, metabolic, and sociodemographic factors contribute to DFU development. The risk increases with longer diabetes duration and sustained hyperglycemia, both of which contribute to vascular complications [5]. Male sex and low socioeconomic status have also been associated with a high risk of ulceration and amputation [6–8]. Chronically elevated glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels are independent risk factors for DFUs and amputation [5]. Smoking contributes to both PAD and DPN [4], further elevating the risk of DFUs and amputation [9–11]. Cardiovascular disease, a leading cause of mortality in patients with DFUs [12], is associated with delayed wound healing and high amputation rates [13,14]. Chronic kidney disease, particularly in patients receiving dialysis, significantly increases the risk of DFUs. Stage 4 chronic kidney disease nearly quadruples the likelihood of ulcer development and increases the risk of amputation sevenfold [15,16]. Diabetic retinopathy is 2–4 times more prevalent in patients with DFUs [17], with severe visual impairment exacerbating gait abnormalities and elevating the risk of ulcer development.

Clinical and socioeconomic significance of DFUs

DFUs are clinically significant owing to challenges in wound healing, high recurrence rates, associated infections, and increased mortality. Healing times for DFUs vary depending on ulcer characteristics and patient factors, with median durations ranging from 3 months to more than 1 year [3]. Large, deep, infected, ischemic plantar ulcers exhibit prolonged healing times [3,11,18]. Approximately 60% of DFUs become infected, increasing morbidity [19], and severe infections can increase amputation rates by up to 90% [20].

Although overall amputation rates have declined, minor amputations have increased, as shown in Korean data from 2011 to 2016 [1], possibly reflecting an expansion of limb-preservation strategies [21]. However, the nearly 50% increase in major amputations observed since 2014 among socioeconomically disadvantaged populations reflects disparities in diabetes care and emphasizes the importance of addressing social determinants of health [22,23].

In addition to clinical consequences, DFUs impose a substantial economic burden. They significantly increase healthcare utilization, including hospitalizations, emergency department visits, outpatient services, and home healthcare, contributing to direct medical costs estimated to be 50–200% higher than those associated with standard diabetes care [24]. Korean data from 2011 to 2016 similarly demonstrated a rising economic burden from DFUs and amputations [1]. These estimates may underestimate the total economic impact because they omit productivity losses and employment disruptions related to DFUs [24].

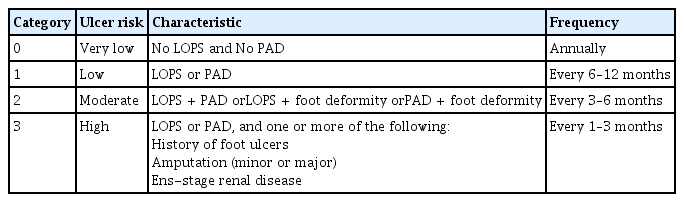

ASSESSMENT

Early identification of at-risk feet or pre-ulcerative lesions can prevent foot ulcers, amputations, and related adverse outcomes. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) and International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) recommend annual foot examinations for all individuals with diabetes and more frequent assessments for those at high risk (Table 1) [25,26]. Comprehensive foot evaluation should include dermatological, neurological, vascular, and musculoskeletal assessments. Clinicians should obtain a thorough history of risk factors for ulceration and amputation, including prior foot ulcers or amputations and symptoms suggestive of DPN or PAD, as well as other contributors, such as impaired vision, nephropathy, smoking, and poor glycemic control [27]. The initial assessment should include careful inspection of the feet for ulcerations, calluses, or nail deformities. Foot deformities, such as claw toe, hammer toe, and Charcot neuroarthropathy, which are more common in people with diabetes, should also be evaluated. These deformities increase plantar pressure and contribute to ulcer development [28]. Additionally, assessment of DPN and PAD, as discussed in detail subsequently, is essential for identifying individuals at risk of developing foot ulcers.

Loss of protective sensation (LOPS)

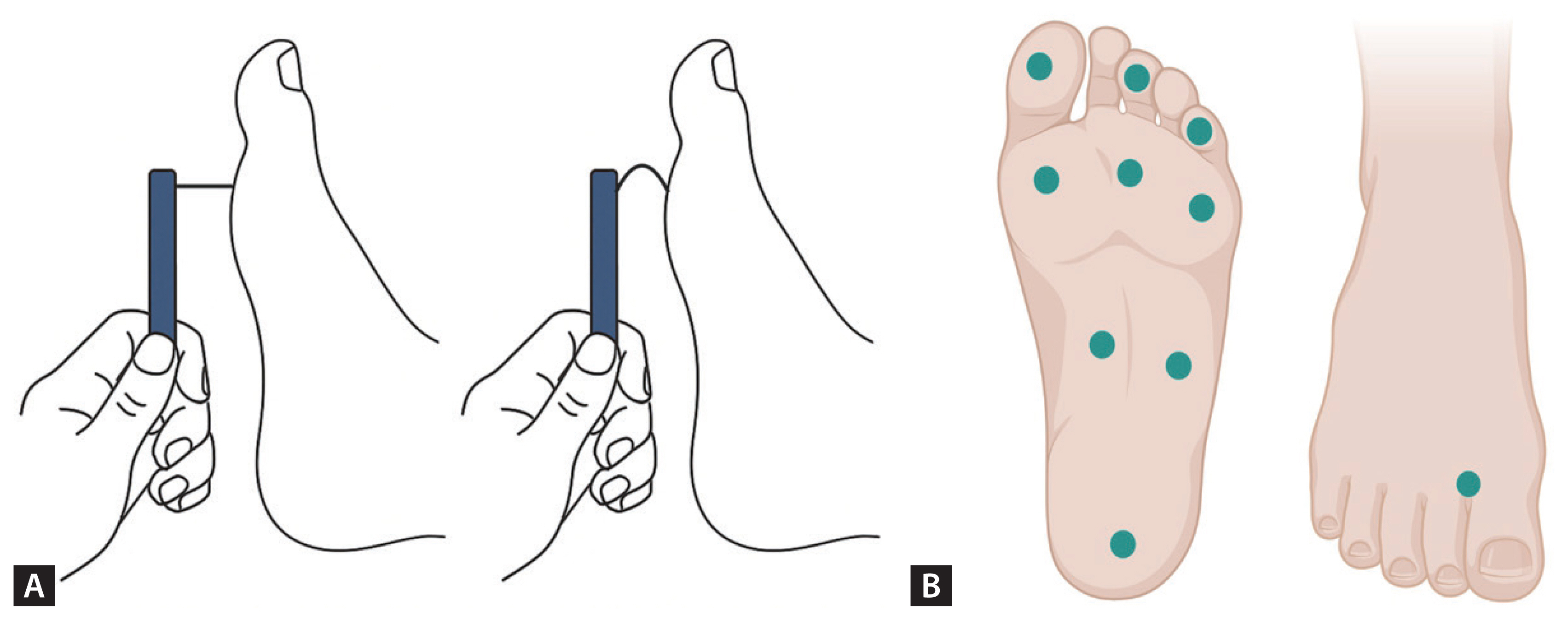

Evaluation of LOPS is crucial for identifying feet at risk for DFUs [27]. The 10-g monofilament test is the most widely used method for detecting LOPS. This is performed by applying the filament perpendicularly to predetermined sites on the foot (such as the great toe, metatarsal heads, and heel) with sufficient pressure to bend it for 1 second. Sensory perception is evaluated at each site with eyes closed (Fig. 1) [29]. According to current ADA guidelines, the diagnosis of LOPS should include the 10-g monofilament test along with at least one other assessment (including pinprick, temperature perception, ankle reflexes, or vibratory perception with a 128-Hz tuning fork or similar device) [26,27]. LOPS is confirmed when monofilament sensation is absent at one or more sites in combination with another abnormal sensory test. The inability to sense 10 g of pressure is strongly associated with a significantly increased risk of DFUs and amputations [30].

PAD

PAD contributes to approximately 50% of foot ulcers and significantly increases the risk of amputations [31,32]. Assessment of PAD is important not only for identifying atrisk feet but also for improving treatment outcomes. Initial screening should include a history of intermittent claudication and rest pain, which are suggestive of PAD, and assessment of the posterior tibial and dorsalis pedis pulses [31,33]. Individuals with suspected PAD should undergo noninvasive arterial studies, including ankle-brachial index (ABI), toe pressure, Doppler waveform, or pulse volume recording. According to the IWGDF, no single modality is optimal for diagnosing PAD [34]. Therefore, a combination of diagnostic approaches is often required for accurate diagnosis. The ABI, calculated by dividing the ankle systolic pressure by the higher of the two brachial systolic pressures, is most widely used to determine the presence of PAD. An ABI ≤ 0.90 is considered diagnostic of PAD, and an ABI < 0.40 is suggestive of severe disease [35]. An ABI ≤ 0.90 is strongly associated (odds ratio: 8.2) with the 7-year risk of amputation in people with diabetes mellitus [36]. In patients with diabetes, the ABI requires careful interpretation because medial calcinosis can render arteries noncompressible. An ABI > 1.40 typically indicates noncompressible vessels [35]. In such cases, toe pressure or toe-brachial index is more reliable than ABI. Toe systolic blood pressure < 30 mmHg or toe-brachial index < 0.70 is considered indicative of PAD [37].

CLASSIFICATION

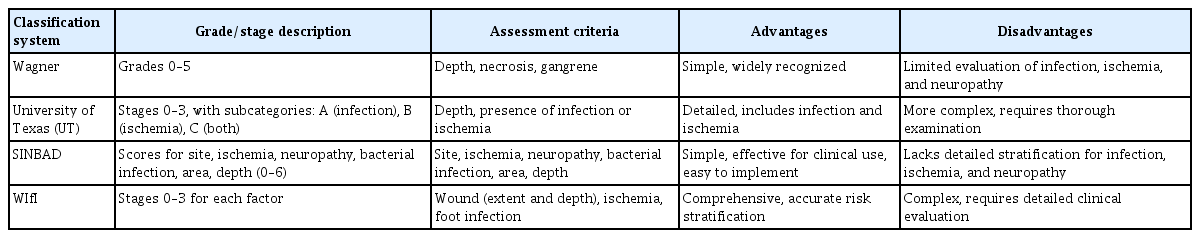

A classification system that describes wound size and depth, presence of infection, PAD, and DPN can help develop treatment strategies and improve communication among multi-disciplinary healthcare teams. Several classification systems for DFUs exist, but none is widely accepted as the gold standard. The Wagner classification system is well known and consists of six grades based on wound depth and the presence of gangrene. Although the Wagner system is simple and has been used extensively, it does not assess DPN or ischemia [38].

By contrast, the University of Texas (UT) system, widely adopted in clinical practice, classifies DFUs into grades 0–3 based on depth and stages A–D based on infection or ischemia [38]. This dual-parameter structure facilitates more accurate risk stratification and treatment planning than those of depth-only systems. The UT system has also demonstrated predictive value for wound healing and amputation risk, underscoring its utility in both clinical and research settings.

More recently, the IWGDF recommended using SINBAD (Site, Ischemia, Neuropathy, Bacterial infection, Area, Depth) as the first-line classification system and considered the WIfI classification system [39]. The WIfI system, developed by the Society for Vascular Surgery, is based on wound severity, ischemia, and infection, the major factors associated with limb loss [40].

All four classification systems can be applied relatively easily in clinical practice, although each has strengths and limitations (Table 2). While the UT and WIfI systems require specific diagnostic tests to assess ischemia, they provide detailed and comprehensive evaluations that can guide effective treatment plans. The selection of an appropriate system should be determined by the clinical setting, available diagnostic tools, and intended objectives.

PREVENTION

Prevention of DFUs requires a multifaceted approach combining regular foot evaluation, glycemic control, and patient education.

Regular foot screening facilitates early detection of risk factors, allowing timely identification and treatment of pre-ulcerative or ulcerative lesions. Because patients with diabetes are often asymptomatic for PAD [35] and highly vulnerable to DFUs owing to DPN-related insensate trauma [41], guidelines recommend comprehensive annual foot evaluations for all patients with diabetes and more frequent assessments for those at high risk [25,26]. Early detection supports prompt referral to multidisciplinary teams, which has been shown to reduce the incidence of DFUs and lower-extremity amputations [42].

Persistent hyperglycemia is associated with an increased risk of DFUs, subsequent amputation, and mortality [5]. A systematic review and meta-analysis indicated that HbA1c levels ≥ 8% and fasting glucose levels ≥ 7.0 mmol/L significantly increase the risk of lower-extremity amputations in patients with DFUs [43]. Evidence suggests that intensive glycemic control improves sensory nerve function, reduces amputation risk, and may decrease the overall incidence of DFUs [44,45]. Therefore, optimal glycemic control can reduce the lifetime risk of DFUs and is crucial for improving outcomes.

Patient education is a fundamental component of prevention. All patients with diabetes and their families should receive structured education on daily foot inspection, proper footwear, glycemic control, and avoidance of minor trauma [26]. While education improves knowledge and behavior related to foot care, its effect on reducing DFUs and amputations remains uncertain [46]. Moreover, simple verbal instructions provide limited and short-term benefits [47,48], highlighting the need for effective and sustained educational strategies, especially for high-risk patients.

MANAGEMENT

Non-invasive treatment

Treatment of infection

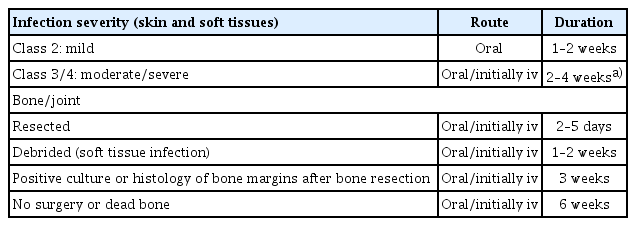

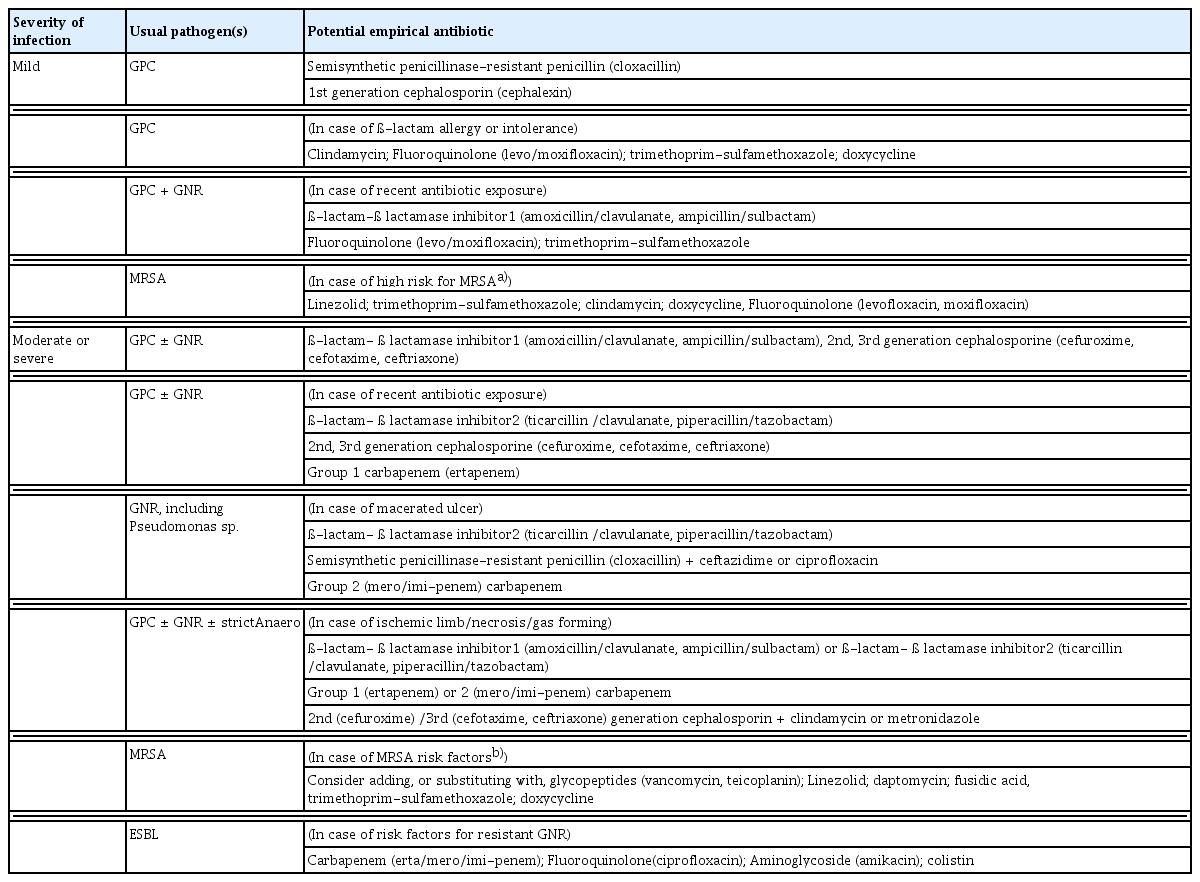

Based on wound size and depth, targeted antibiotics are prescribed as initial therapy for infected DFUs. Although all wounds require local treatment (including debridement, dressings, and pressure offloading), only infected wounds require antibiotics. Topical antibiotics can be used for open or superficial wounds and include gentamicin, neomycin, chloramphenicol, mupirocin, and bacitracin [49]. For clinically infected wounds, it is recommended to obtain a tissue specimen for culture (and a Gram-stained smear, if available) and avoid swab cultures. Infected DFUs should first be treated with empiric antibiotics according to the likely causative pathogen and infection severity [50]. Staphylococcus aureus is the predominant pathogen in most mild infections. If the infection does not resolve, therapy should be adjusted to target bacteria identified from cultures. Chronic and more severe infections are often polymicrobial; therefore, for deep or extensive (potentially limb-threatening) infections, empiric parenteral broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy targeting common gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, including obligate anaerobes, is initiated [51]. The recommended empiric antibiotic therapy is dicloxacillin, cephalexin, clindamycin, or amoxicillin/clavulanate for mild to moderate cases; vancomycin plus ampicillin/sulbactam, moxifloxacin, cefoxitin, or cefotetan for moderate cases; and vancomycin plus piperacillin/tazobactam, imipenem/cilastatin, or meropenem for severe cases [52]. Definitive therapy is modified according to culture and sensitivity results and the response to empiric treatment. To reduce the likelihood of antibiotic resistance, therapy should target cultured pathogens and be administered for the shortest duration necessary. Antibiotics treat infections but do not heal or prevent them [53]. They can be discontinued once the clinical signs and symptoms of infection resolve rather than continued until the wound is healed. Thus, although a foot wound may take months to heal, antibiotic duration depends on infection severity: 1–2 weeks is sufficient for mild infection and 2–4 weeks for severe infection. Long-term suppressive antibiotic therapy is generally warranted only for individuals with retained orthopedic hardware or extensive necrotic bone not amenable to complete debridement [54]. Clinicians should consider consultation with an infectious disease or microbiology expert for difficult cases, such as those caused by unusual or highly resistant pathogens [55]. Proposed regimens for empiric antibiotic therapy and treatment duration in DFU infections are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

Proposals for empirical antibiotic therapy according to the clinical severity of diabetic foot infections

Wound dressing in DFUs

Dressings are an essential component of local wound care, as they support ulcer healing by maintaining a moist, insulated, clean environment. Current clinical guidelines recommend individualized dressing selection based on wound characteristics, including exudate volume, depth, presence of slough or necrotic tissue, and clinical signs of infection [56]. Despite the wide range of available products, the overall quality of evidence supporting their efficacy remains limited. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have provided moderate-quality evidence supporting the use of hydrogel dressings as desloughing agents [57], whereas evidence is insufficient to recommend the routine use of antiseptics or other topical dressings in clinical practice [58].

Antithrombotic therapy

In patients with DFUs and PAD, antithrombotic therapy may be considered as an adjunct to reduce ischemia-related complications and support limb preservation. The IWGDF and ADA recommend single antiplatelet therapy, typically with aspirin (75–162 mg/d) or clopidogrel (75 mg/d) [34,59]. As an alternative, combination therapy with aspirin (75–100 mg once daily) and low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) may be considered for patients at low risk of bleeding. The COMPASS trial showed that combination therapy significantly reduced major cardiovascular events and limb-related complications, including acute or chronic limb ischemia and major amputations, compared with aspirin alone [60]. Importantly, in patients with DFUs and PAD, the timing of revascularization should not be delayed because of antithrombotic therapy.

Invasive treatment

Surgical treatment of DFUs

In general, the surgical treatment of DFUs requires adequate vascular supply to sustain invasive procedures. Clinically, surgical management includes conservative sharp wound debridement (CSWD), offloading procedures, operative interventions for infection control, and amputation [61–63].

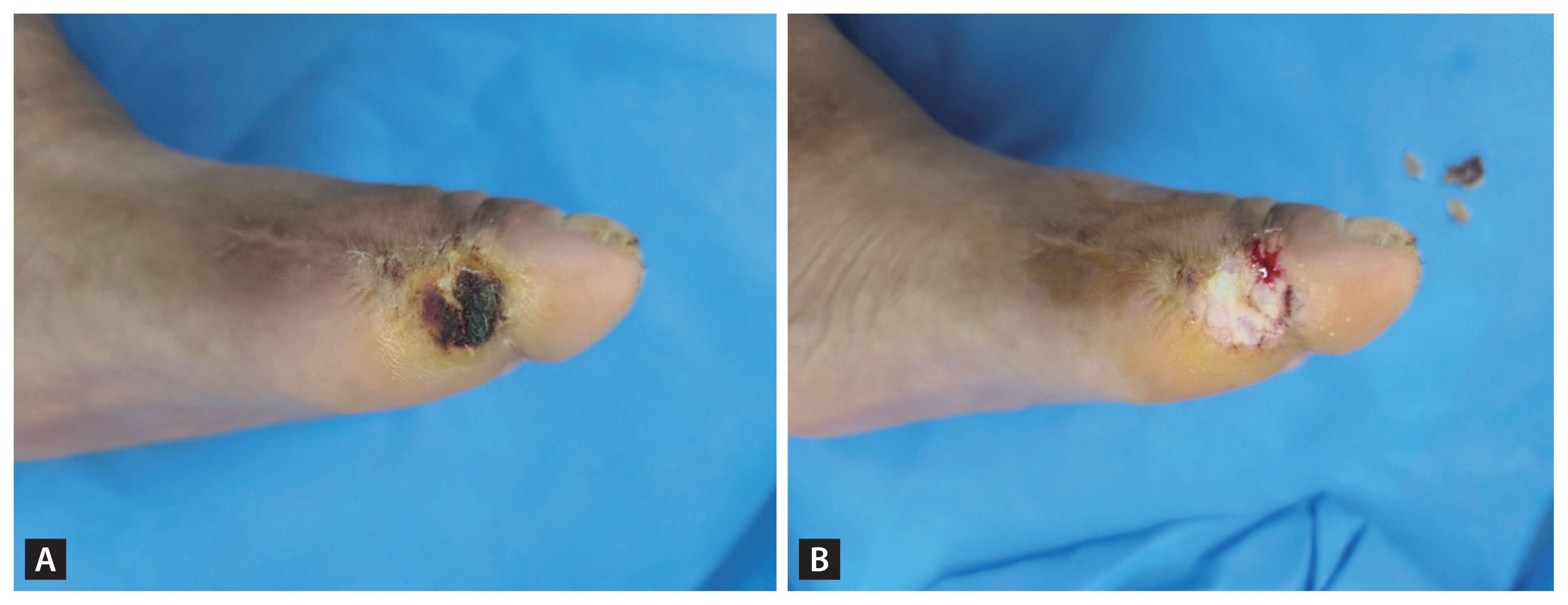

CSWD

CSWD converts a chronic wound stalled in the inflammatory phase into an acute wound, thereby triggering healing and creating an environment for healthy granulation tissue formation by removing devitalized tissue [64]. CSWD reduces bacterial burden and inflammatory cytokines and removes biofilms. When callus coexists with DFUs, plantar pressure can be relieved by CSWD (Fig. 2).

Offloading procedures

Shear stress and direct compressive pressure are causative factors in DFUs [65,66]. Therefore, management of deformities or prominences that cause high-pressure loading in the foot and ankle is a crucial component of DFU treatment [67]. When internal bony prominences hinder healing despite conservative measures, such as shoe modification or total contact casting, surgical intervention— such as resection of the prominence, realignment, or correction of structural deformity—should be considered.

Surgical intervention for diabetic foot infection

Surgical treatment of diabetic foot infections focuses on limb salvage. An aggressive and prompt approach is essential to preserve the foot and prevent proximal spread of infection. Initial surgical intervention typically consists of incision and drainage with thorough debridement of necrotic soft tissue and bone, particularly in deep infections or acute abscesses.

Osteomyelitis in DFUs is a particularly challenging problem. There is growing consensus supporting surgical resection and wide debridement of the affected bone in established cases [68]. Bone culture is essential for identifying causative organisms and selecting appropriate antibiotics [69,70]. Although debate continues regarding the extent and necessity of surgery in osteomyelitis, surgery combined with antibiotics produces complementary and synergistic effects [68].

Amputations

Even with advanced evaluation and management, severe infection or ischemic necrosis in patients with diabetes who have uncontrolled infections or non-healing wounds may necessitate lower-extremity amputation [71]. The main principle of amputation is to preserve walking function with the lowest possible energy expenditure [72,73]. However, the level and timing of amputation are determined by factors, such as infection, vascular status, and comorbid medical conditions [25,74]. They are also influenced by patients’ socioeconomic, functional, and psychological status and the availability of caregivers [75].

The primary goal should be to improve patients’ quality of life rather than to preserve the limb at all costs.

Vascular intervention (endovascular treatment)

Foot revascularization is often necessary for patients with chronic limb-threatening ischemia [76]. Delayed revascularization increases the risk of major amputation (odds ratio, 3.1; 95% confidence interval, 1.4–6.9) [77]. Endovascular treatment of DFUs focuses on minimally invasive procedures that improve blood flow and reduce amputation risk. These treatments are increasingly used not only in patients unsuitable for surgery because of frailty but also as a first-line option [78]. However, features, such as multi-segmental long lesions, complete occlusions, severe calcification, poor collateral circulation, and small-vessel involvement below the knee, which are common in DFUs, make treatment more challenging [79]. In these cases, surgical treatment may be more effective. The choice of treatment depends on lesion anatomy and patient condition. We provide a comprehensive overview of commonly used endovascular treatment methods.

Balloon angioplasty

This is one of the most common endovascular procedures used to treat PAD in patients with diabetes. A small balloon is inserted at the site of the arterial blockage, which is then inflated to widen the artery and restore blood flow. Drug-coated balloons are particularly effective in preventing restenosis by releasing medications that inhibit cell proliferation [80]. Retrograde endovascular therapy can be used to access and treat blockages against the normal direction of blood flow, typically when antegrade approaches are not feasible [81].

Stent placement

Following balloon angioplasty, stents may be placed to keep arteries open. Bare-metal stents and drug-eluting stents are commonly used. Drug-eluting stents are coated with drugs that reduce the risk of restenosis, making them preferable for maintaining long-term patency [82].

Atherectomy

This procedure removes plaque from arterial walls using a catheter with a cutting device. Atherectomy is particularly useful in patients with diabetes and heavily calcified arteries, in whom traditional balloon angioplasty may be less effective [83].

Advanced imaging techniques

The use of intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography during endovascular procedures aids precise device placement and assessment of treatment effectiveness. These techniques enhance accuracy and improve outcomes. Intravascular ultrasound provides detailed imaging of the vessel wall and lumen, facilitating better decision-making. Optical coherence tomography offers high-resolution images that allow evaluation of stent apposition and identification of issues not visible on angiography [84].

Bypass surgery

Bypass surgery is a crucial treatment option for DFUs, particularly when endovascular interventions are inadequate. When a single-segment great saphenous vein is available, it effectively reduces major amputations and major reinterventions compared with endovascular treatments [85].

Bypasses are often performed in the tibial or pedal arteries, which are commonly affected in diabetes. This procedure significantly improves foot perfusion and enhances ulcer healing. Distal bypass to the dorsalis pedis or posterior tibial arteries around the ankle can be challenging but offers significant benefits. These bypasses are critical for restoring adequate distal perfusion, promoting ulcer healing, and preventing amputation because these arteries are often preserved [86].

Venous arterialization

In complex cases in which traditional bypass routes are not feasible, venous arterialization may be considered. This technique redirects arterial blood into the venous system to improve foot perfusion. Patients with severe limb ischemia often lack arterial runoff vessels below the malleolar level, making standard bypass infeasible. An alternative approach involves arterializing the venous system of the foot. This can be achieved surgically by creating an anastomosis between the arterial system and either the great saphenous vein or a deep vein, such as the posterior tibial vein, along with valve destruction to allow arterial flow through the venous system. A hybrid method combining surgical and endovascular techniques can also be used to destroy valves and close side branches endovascularly [87].

The success rates of limb salvage after venous arterialization vary. Alexandrescu et al. [88] reported a 73% limb salvage rate at 2 years in a study of 25 patients with diabetes using a hybrid technique. However, a smaller study involving 10 patients showed mixed results, underscoring the need for larger studies with longer follow-up to better evaluate the effectiveness of this technique, particularly in patients with diabetes.

These surgical interventions are tailored to each patient’s anatomical and clinical conditions, with the goals of restoring adequate blood flow, promoting wound healing, and preventing major amputation. To achieve optimal results, each technique requires careful consideration of the patient’s overall health, extent of vascular disease, and ulcer characteristics. However, in patients with impaired functional status or limited life expectancy, primary lower-extremity amputation may be more appropriate than revascularization [78].

CONCLUSION

The management of DFUs requires individualized approaches rather than generalized strategies, guided by the etiology, severity, and overall condition of the patient. This review highlights the importance of risk-based, patient-centered interventions that integrate timely diagnosis, multidisciplinary collaboration, and appropriate medical and surgical management, including judicious antibiotic use and targeted vascular or orthopedic procedures.

Ultimately, DFU care should aim not only at limb preservation but also at improving quality of life and functional recovery. To achieve this, healthcare systems must actively invest in structured foot screening, patient education, and comprehensive team-based care to reduce the burden of amputation and its long-term complications.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Ji Min Kim: methodology, writing - original draft; Chong Hwa Kim: conceptualization, methodology, writing - original draft; Seon Mee Kang: writing - original draft; Jung Hwa Jung: writing - original draft; Ki Chun Kim: writing - original draft; Sanghyun Ahn: writing - original draft; Tae Sun Park: conceptualization, writing - review & editing; Ie Byung Park: methodology, writing - original draft

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None