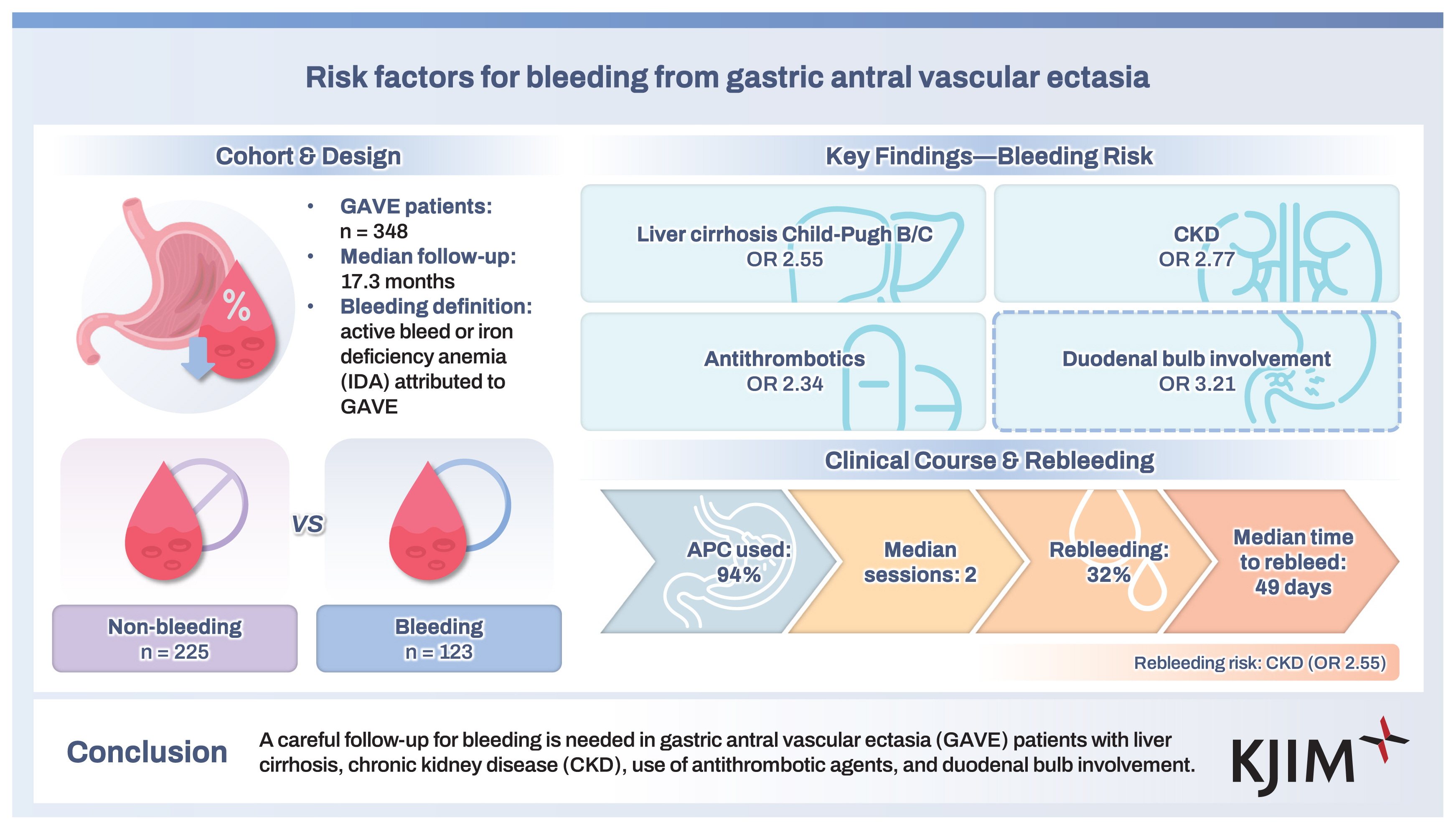

Risk factors for bleeding from gastric antral vascular ectasia

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is a rare but important cause of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. The clinical course of GAVE is not well-known, and recurrent bleeding from GAVE is a therapeutic challenge. Therefore, we investigated the clinical course of GAVE and identified the risk factors for bleeding from it.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of patients diagnosed with GAVE using upper GI endoscopy at Asan Medical Center between January 2004 and December 2019 and evaluated the clinical course and risk factors for bleeding from GAVE.

Results

Of the 348 patients (mean age, 62.3 ± 10.7 years; male, 62%), bleeding from GAVE occurred in 123 (35%) patients during follow-up (median, 17.3 months; interquartile range [IQR], 4.2–46.6). GI bleeding from GAVE was significantly associated with Child–Pugh class B or C liver cirrhosis (odds ratio [OR], 2.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.57–4.16), chronic kidney disease (CKD) (OR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.52–5.07), use of antithrombotic agents (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.13–4.82), and involvement of the duodenal bulb (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.76–5.86). Rebleeding occurred in 39 of 123 patients (32%), in whom CKD (OR, 2.55; 95% CI, 1.12–5.81) was significantly associated with rebleeding. Endoscopic hemostasis was most commonly performed using argon plasma coagulation, and the median number of endoscopic hemostasis performed was 2 (IQR, 1–3).

Conclusions

A careful follow-up for bleeding is needed in GAVE patients with liver cirrhosis, CKD, use of antithrombotic agents, and duodenal bulb involvement.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), which is also referred to as watermelon stomach, is a rare but important cause of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. GAVE is usually diagnosed by upper GI endoscopy showing characteristic appearances. Histologic findings of GAVE include dilatation of mucosal capillaries with fibrin thrombi, fibromuscular hyperplasia of the lamina propria, and fibrohyalinosis around the ectatic capillaries [1]. The pathogenesis of GAVE is not well-known, but underlying diseases such as liver cirrhosis, autoimmune disease, connective tissue disease, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) are related to GAVE [1–4].

Patients with GAVE may initially present with asymptomatic chronic occult GI bleeding with concurrent iron deficiency anemia or symptomatic acute upper GI bleeding [5]. In a previous prospective study, GAVE accounted for 4% of cases with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding [6]. Various endoscopic therapies, surgical treatment, and hormonal therapies [7–9] have been developed for the management of bleeding from GAVE. From among these, argon plasma coagulation (APC) is a safe and effective endoscopic modality for treating GI bleeding from GAVE and has been recognized as first-line endoscopic therapy [10–14]. Although APC has a high efficacy and good safety profile in the management of initial bleeding from GAVE, recurrent bleeding events from GAVE frequently occur, and re-treatment of bleeding is often necessary [10]. As such, early detection of patients with a high risk of bleeding from GAVE is important in treating bleeding from GAVE and improving their prognosis.

The clinical course and the bleeding risk of GAVE are not well-known, and recurrent bleeding from GAVE is a significant therapeutic challenge. To date, a limited number of small-sized studies have been reported on the risk factor for bleeding from GAVE [15,16]. Therefore, we examined the clinical course of GAVE and identified the risk factors for bleeding from it by analyzing a large volume of data gathered in a single tertiary referral center.

METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the database at Asan Medical Center to retrieve information on consecutive patients with GAVE who underwent upper GI endoscopy between January 2004 and December 2019. GAVE was diagnosed and recorded in the electronic medical records by an endoscopist at the initial session of endoscopy. We excluded patients with the following endoscopic findings: (1) no mucosal lesions on the antrum, (2) incomplete endoscopic evaluation due to food stasis, (3) continuous mucosal lesions from the antrum to the corpus and/or fundus in patients with liver cirrhosis that are consistent with endoscopic findings of portal hypertensive gastropathy, (4) presence of multiple erosions and/or ulcers on the antrum, and (5) single vascular ectasia lesion on the gastric antrum.

We collected information on the demographics, comorbidities, history of radiation therapy to the upper abdomen, initial laboratory tests, amount of packed red blood cell transfusions, and endoscopic findings of GAVE, including the location, types, and bleeding signs. The history of radiation therapy to the upper abdomen was evaluated only when radiation therapy was performed before the diagnosis of GAVE. Modalities used for endoscopic hemostasis were also reviewed. Liver cirrhosis, autoimmune disease, connective tissue disease, and CKD were chosen as comorbidities for evaluation based on previous studies suggesting the close relationships between these comorbidities and GAVE [1–4]. The final follow-up period for the patients included herein ended in December 2020. The protocols of this study were approved by the institutional review board of Asan Medical Center (IRB number: 2020-1147).

Endoscopic findings and treatment

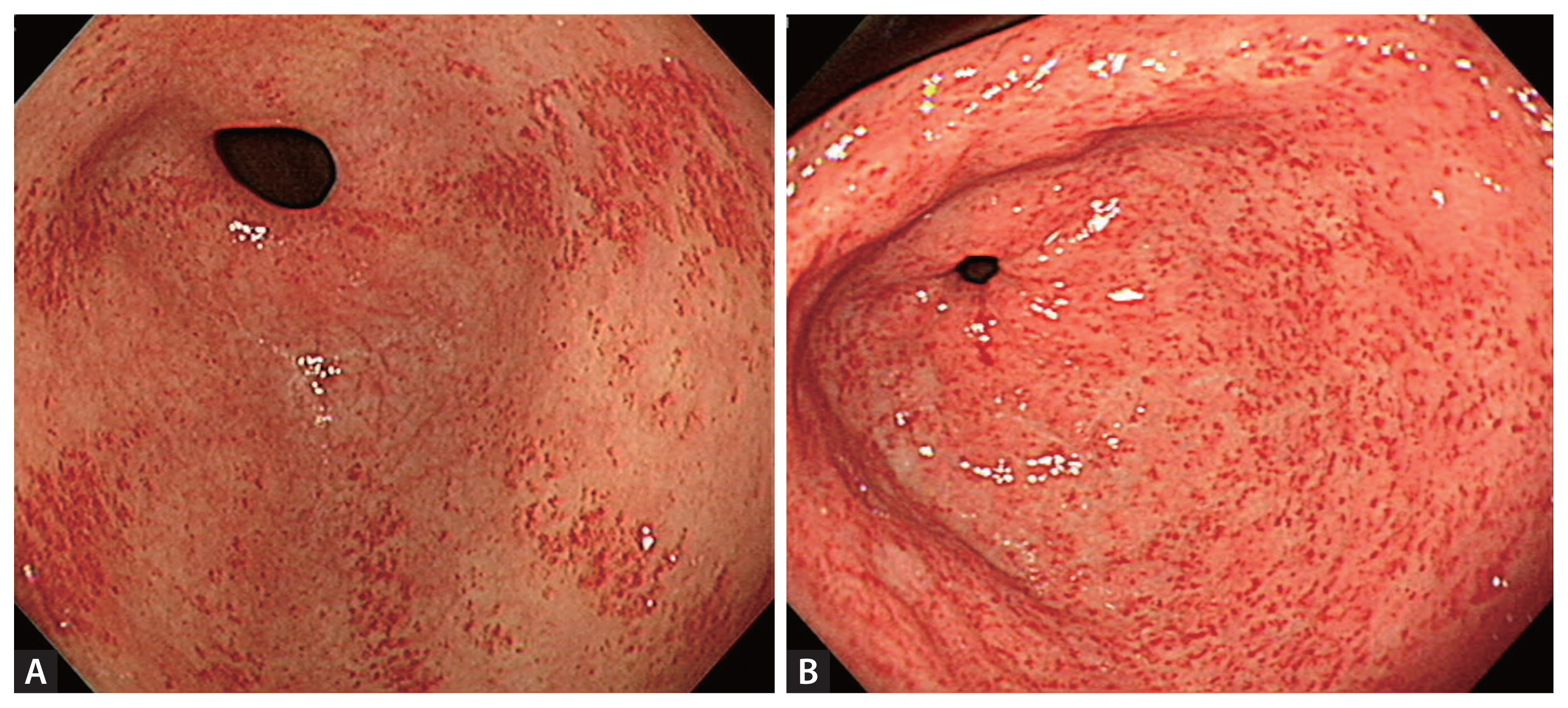

GAVE was diagnosed by characteristic endoscopic findings such as erythematous folds radiating longitudinally from the pylorus and sharply demarcated punctate red spots scattered diffusely through the antrum. Mucosal lesions that were only observed in the corpus and/or fundus rather than the antrum were not considered as findings of GAVE. When the findings of GAVE were noted on upper GI endoscopy, prophylactic endoscopic procedures for preventing GI bleeding were not routinely performed. Follow-up upper GI endoscopy was not performed in patients with GAVE when there was no evidence of GI bleeding, such as decreased hemoglobin, or bleeding symptoms, including hematemesis, melena, and hematochezia. At our center, single or combination methods with spraying or injection of epinephrine (1:10,000 solution of epinephrine), APC, metal hemoclip (HX-600-09-L or HX-110LR; Olympus Optical Col, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), coagrasper (FD-410LR; Olympus), and spraying or injection of fibrin glue (Beriplast P 3 mL Combi-Set; Behring Pharma, Tokyo, Japan) were available when endoscopic hemostasis was performed. The type of procedure was chosen at the discretion of the attending endoscopists. APC was frequently performed with an electrocoagulation unit (APC 2; Erbe Elektromedizin, Tübingen, Germany) to ablate the bleeding focus from GAVE; the gas flow rate was 1.8 L/min, and the electrical current was set as 40, 60, or 80 W.

Definition

GAVE was categorized into two types—striped and punctate. The striped type was defined as erythematous folds radiating longitudinally from the pylorus on endoscopic images, and the punctate type was defined as sharply demarcated, punctate red spots scattered diffusely through the antrum [16] (Fig. 1). GI bleeding from GAVE was defined as (1) upper GI endoscopy showing grossly active bleeding from GAVE, or (2) GAVE was considered the cause of iron deficiency anemia when lower GI bleeding was excluded via both capsule endoscopy and colonoscopy. Patients who met this definition during the study follow-up period were classified into the bleeding group. Therefore, no patients in the non-bleeding group experienced GI bleeding from GAVE during the study follow-up period. Rebleeding was defined as recurrent bleeding developing at least 7 days after the initial bleeding from GAVE. GI bleeding from any lesions (e.g., gastric varix, angiodysplasia, erosions, ulcers) in the stomach apart from GAVE was excluded from the bleeding and rebleeding groups. Liver cirrhosis was categorized according to the Child–Pugh classification [17,18].

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes in this study included factors associated with GI bleeding from GAVE. The secondary outcomes included factors associated with rebleeding from GAVE and the clinical courses after initial bleeding from GAVE.

Statistical analyses

Results are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) or mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous parameters, and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. We selected statistically significant factors and performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to identify the factors associated with bleeding and rebleeding from GAVE. The final multivariate model was constructed with the stepwise forward conditional method. Each variable was entered into the model if the probability of its score was less than.05 and was removed when the probability score was greater than.10. p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

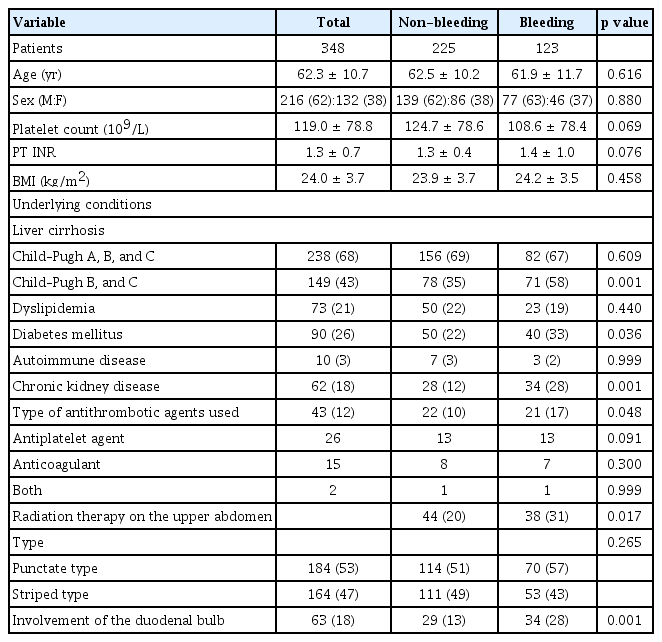

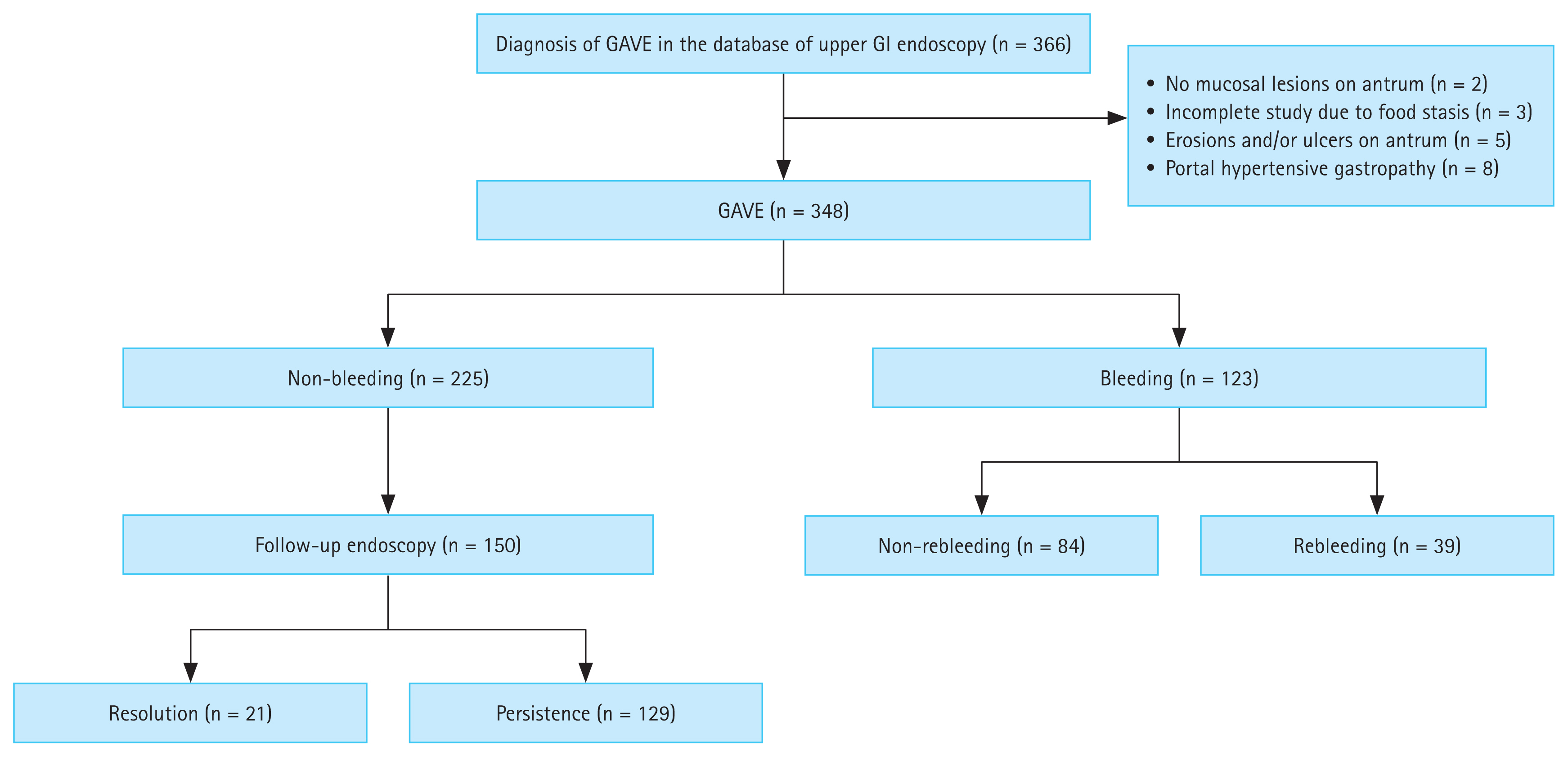

A total of 348 consecutive patients (non-bleeding, n = 225; bleeding, n = 123) were included in the analysis (Fig. 2). The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 62.3 ± 10.7 years, and 62% were male. Ten patients had autoimmune disease, of whom four patients had autoimmune hepatitis, four patients had systemic lupus erythematosus, one patient had Behcet’s disease, and one patient had rheumatoid arthritis. A total number of 82 patients underwent radiation therapy, including those with hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 55), cholangiocarcinoma (n = 16), gallbladder cancer (n = 6), pancreatic cancer (n = 4), and ovarian cancer (n = 1). The target organs of radiation therapy were the portal vein (n = 29), lymph nodes (n = 17), bile duct (n = 15), liver (n = 8), gallbladder (n = 6), pancreas (n = 4), and inferior vena cava (n = 3). In all cases, the gastric antrum and duodenal bulb were included within the radiation field. During a median follow-up of 17.3 months (IQR, 4.2–46.6), bleeding from GAVE occurred in 123 (35%) patients. A total of 22 (6%) patients showed spontaneous resolution of GAVE in follow-up endoscopic examination; among them, 21 patients showed resolution of GAVE without any endoscopic treatment of lesions, and the remaining one patient showed resolution on follow-up endoscopy after undergoing endoscopic hemostasis using APC (Fig. 3). Among the patients who showed resolution of GAVE, 9 patients with liver cirrhosis and 1 patient with CKD showed spontaneous resolution of mucosal lesions of the antrum after liver transplantation and after kidney transplantation, respectively. The rates of all-cause mortality and bleeding-related mortality were 60% and 2%, respectively.

Flowchart summarizing the clinical courses of GAVE. GAVE, gastric antral vascular ectasia; GI, gastrointestinal.

Endoscopic images of GAVE resolution after APC. (A, B) Initial endoscopic finding showing bleeding from GAVE. (C, D) APC was performed to control the bleeding from GAVE. (E, F) Follow-up endoscopic image at 6 months showing spontaneous resolution of GAVE. APC, argon plasma coagulation; GAVE, gastric antral vascular ectasia.

Factors associated with bleeding from GAVE

Comparisons of the baseline characteristics and underlying disease between the non-bleeding and bleeding groups are presented in Table 1. The non-bleeding and bleeding groups showed significant differences in the proportion of those with Child–Pugh class B or C liver cirrhosis (35% vs. 58%; p = 0.001), diabetes mellitus (22% vs. 33%; p = 0.036), CKD (12% vs. 28%; p = 0.001), use of antithrombotic agents (10% vs. 17%; p = 0.048), history of radiation therapy to the upper abdomen before the diagnosis of GAVE (20% vs. 31%; p = 0.017), and involvement of the duodenal bulb (13% vs. 28%; p = 0.001). Of the patients treated with antithrombotic agents, 26 patients received antiplatelet agents (aspirin, n = 11; clopidogrel, n = 6; ticlodipine, n = 1; combination of aspirin and clopidogrel, n = 8), 15 patients received anticoagulants (warfarin, n = 13; ribaroxaban, n = 2), and the remaining 2 patients received a combination of aspirin and warfarin.

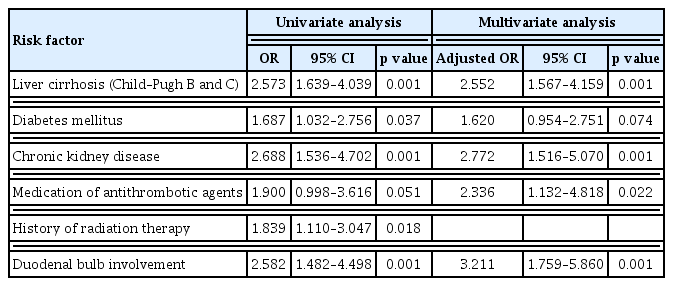

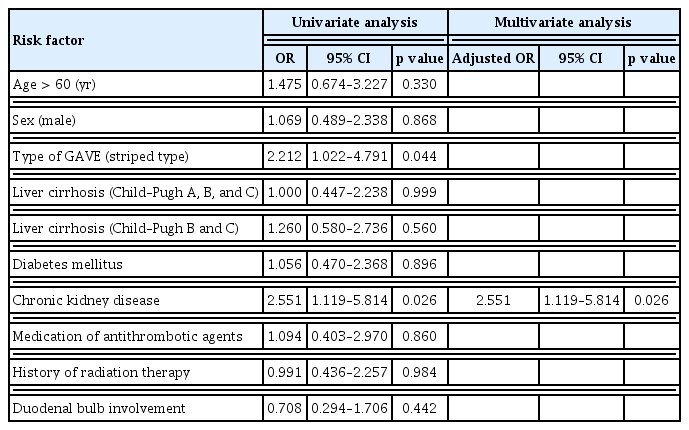

Based on these results, Child–Pugh class B or C liver cirrhosis, CKD, use of antithrombotic agents, history of radiation therapy to the upper abdomen, and involvement of the duodenal bulb were chosen as potential risk factors associated with bleeding from GAVE and were included in logistic regression analysis. After adjusting for confounding variables, multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that Child–Pugh class B or C liver cirrhosis (odds ratio [OR], 2.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.57–4.16), CKD (OR, 2.77; 95% CI, 1.52–5.07), use of antithrombotic agents (OR, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.13–4.82), and involvement of the duodenal bulb (OR, 3.21; 95% CI, 1.76–5.86) were significantly associated with GI bleeding from GAVE (Table 2).

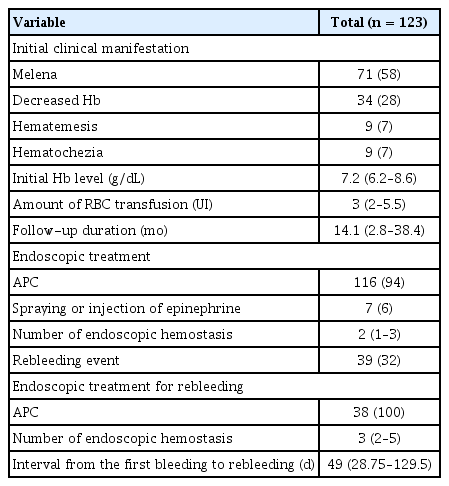

Clinical course after initial bleeding from GAVE

We evaluated the clinical course of GAVE after initial bleeding. The results in this subgroup analysis are summarized in Table 3. In 123 patients with bleeding from GAVE, the most common clinical presentation was melena (58%), followed by decreased level of hemoglobin (28%). APC was the most frequently used modality for endoscopic hemostasis (94%) (Fig. 3A–D). The median number of endoscopic hemostasis performed was 2 (range, 1–3). The median amount of packed red blood cell transfusion required for maintaining the hemoglobin level at 9 mg/dL was 3 units (IQR, 2–5.5).

During follow-up, rebleeding occurred in 32% of the patients. The median interval from the first bleeding to rebleeding was 49 days (IQR, 28.8–129.5). All of the 7 patients with bleeding-related mortality had decompensated liver cirrhosis and underwent endoscopic bleeding control when bleeding from GAVE was noted during an endoscopic evaluation. Successful hemostasis was confirmed by inspection immediately after endoscopic hemostasis during an endoscopic session. However, multiorgan failure induced by the aggravation of decompensated liver cirrhosis and GI bleeding progressed to death.

We performed univariate and multivariate analyses in the bleeding subgroup to identify factors associated with rebleeding from GAVE (Table 4). Thus, multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that CKD (OR, 2.55; 95% CI, 1.12–5.81) was significantly associated with rebleeding from GAVE. In the non-bleeding group, 150 (66.7%) patients underwent follow-up endoscopy for reasons such as upper GI symptoms without bleeding symptoms and cancer surveillance. In follow-up endoscopy, 21 (14%) patients showed resolution of GAVE. Prophylactic endoscopic hemostasis was not performed in this group.

DISCUSSION

In this study on 348 consecutive patients with GAVE, we found that initial GI bleeding from GAVE was associated with Child–Pugh class B or C liver cirrhosis, CKD, use of antithrombotic agents, and involvement of the duodenal bulb, whereas rebleeding from GAVE was significantly associated with CKD. Rebleeding from GAVE occurred frequently (32%), and repeated endoscopic hemostasis using APC was also needed. To our knowledge, this is the largest retrospective single-center study on the clinical course of GAVE.

A case series of 110 patients with GAVE, including 26 non-cirrhotic patients, reported that the risk of GI bleeding was higher in patients without cirrhosis than those with it [15]. Another comparative study of 30 patients with GAVE showed that the presence of cirrhosis did not significantly affect the overall clinical outcomes [16]. Our study involving a larger number of patients also showed no significant differences between the bleeding and non-bleeding groups in terms of the presence of liver cirrhosis. However, after categorizing the severity of liver cirrhosis according to Child–Pugh scores, we found that the presence of Child–Pugh B or C liver cirrhosis was significantly associated with GI bleeding from GAVE, which is in contrast with the previous studies. After adjusting for potential confounding variables, multivariate analysis also showed that Child–Pugh B or C liver cirrhosis was significantly associated with bleeding from GAVE.

In our study, 63 (18%) patients with GAVE had involvement of the duodenal bulb, and it was a significant factor associated with bleeding from GAVE. A possible explanation of this finding is that a larger extent of the involvement of GAVE may contribute to increases in the possibility of bleeding. A previous study showed that multiple lesions of angiodysplasia were a predictive factor of recurrent bleeding [19]. However, involvement of the duodenal bulb was not significantly associated with rebleeding from GAVE in our study. Although lesions of GAVE are observed almost exclusively in the antrum, there are reports of some cases in which the extent of lesions included the duodenum and jejunum [20]. A study on the efficacy of APC for controlling bleeding from GAVE also included patients with duodenal involvement (4 [19%] of 19 patients). Thus, the duodenum should be closely inspected during upper GI endoscopy to locate the bleeding focus, especially in cases with GI bleeding from GAVE. Furthermore, prophylactic endoscopic hemostasis may be considered to prevent GI bleeding in patients with GAVE who have factors associated with bleeding.

Furthermore, CKD was the only factor associated with rebleeding from GAVE in multivariate analysis. CKD is one of the causes of upper GI bleeding, which is related to angiodysplasia [21,22]. In a similar vein, CKD significantly increased the risk of early readmission (OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.44–1.82; p < 0.001) in patients with GAVE based on a USA national readmission database study [23]. Previous studies have shown that GI bleeding in patients with CKD may have various mechanisms, including uremia-induced platelet dysfunction, increased risk of vascular malformation, heparinization during hemodialysis, and abnormal function of von Willebrand factor [21,24,25]. Those mechanisms may also contribute to bleeding from GAVE, and our study showed that CKD was a risk factor for both bleeding and rebleeding from GAVE. In addition, patients with CKD often have impaired GI motility with delayed gastric emptying [26,27]. GAVE is presumed to be caused by mechanical injury and shows histologic findings of muscular hyperplasia and fibrosis of lamina propria, which are similar to histologic findings in other types of traumatic intestinal injury such as intussusception and solitary rectal ulcers [28,29]. These findings suggest that mechanical mucosal stress caused by impaired GI motility in patients with CKD may play a role in the development of vascular ectasia in the antrum of the stomach.

APC is a noncontact thermal hemostatic method using a jet of ionized argon gas through a probe [30,31]. It is the most commonly used endoscopic treatment modality owing to its technical ease, safety, and ability to treat large superficial lesions in a single session [30–33]. However, it has been reported to have a relatively high recurrence rate, necessitating repeated procedures. Consequently, new ablative therapies such as endoscopic band ligation (EBL), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and cryotherapy have been applied to GAVE [32]. In a prospective randomized study with 88 cirrhotic patients with GAVE, EBL revealed a significantly decreased number of sessions required for complete ablation of lesions compared to APC [34]. In several recent meta-analyses comparing the efficacy of EBL versus APC for patients with GAVE, EBL showed superiority over APC in terms of the eradication rates of GAVE, recurrent bleeding, and transfusion requirements [35,36]. However, the recurrence rate following EBL was also reported as high as 50% [37], and there could be a technical difficulty in applying re-EBL to fibrotic areas related to previously performed banding [36]. Some studies have reported that RFA is effective to treat APC-refractory GAVE [38–41]. In a retrospective study comparing the efficacy of RFA and APC, RFA did not prove superior to APC [42]. In a meta-analysis including 24 APC and 9 RFA studies, RFA showed fewer mean treatment sessions and fewer complications compared to APC, but hemoglobin increase and reduction in transfusion dependence were higher for APC [43]. Although the long-term data on RFA for GAVE is limited, RFA seems to be as effective as APC and could be applied to APC-refractory GAVE cases.

In our data, the analysis of rebleeding rates according to the endoscopic hemostasis modality showed that all rebleeding occurred in the APC-treated group (39 out of 116 patients), whereas no rebleeding was observed in the spraying or injection of epinephrine group. However, it does not necessarily indicate that APC is associated with a higher risk of rebleeding. Several factors should be considered in the interpretation of these findings. First, the choice of hemostatic modality may have been influenced by the severity of bleeding, with spraying or injection of epinephrine potentially being selected for cases of less severe bleeding, whereas APC was more frequently used for significant bleeding events. This potential selection bias may have contributed to the observed difference in rebleeding rates. Second, the number of patients who underwent spraying or injection of epinephrine was relatively small (n = 7, 6% of the total bleeding cases), which limits the ability to draw statistically meaningful conclusions regarding differences in rebleeding rates between the treatment modalities. However, more extensive randomized controlled studies comparing the efficacy of various endoscopic hemostasis methods for GAVE are required to determine the optimal treatment approach for GAVE-related bleeding.

In the clinical course of GAVE, bleeding-related mortality was low (2%); however, bleeding and/or rebleeding events frequently occurred, and endoscopic hemostasis was also frequently required. Life-threatening massive bleeding rarely occurred during follow-up, and APC for hemostasis was successfully performed in almost all cases with bleeding. Previous studies also showed low mortality [15,23,44] and high clinical success of APC for the management of GAVE [10–12,33]. Comorbidities of liver cirrhosis and CKD, which are risk factors for bleeding, are not improved by medical management and often progress to aggravation. These difficult-to-manage risk factors may contribute to a high rebleeding rate despite repeated endoscopic hemostasis.

Spontaneous endoscopic resolution of GAVE without endoscopic management was noted in 6% (21/348) of patients in follow-up upper GI endoscopy, which suggests that GAVE may be a reversible disease entity. Among those who showed resolution of GAVE, 9 patients with liver cirrhosis and 1 patient with CKD showed spontaneous endoscopic resolution of GAVE after liver transplantation and kidney transplantation, respectively. During follow-up, 34 patients underwent liver transplantation, among whom 9 (26%) patients showed complete resolution of GAVE on follow-up endoscopy. A case report described two cases of persistent portal hypertension that showed complete disappearance of GAVE after liver transplantation [45]. Collectively, these results suggest that GAVE may be resolved by improving comorbidities closely related to GAVE such as liver cirrhosis and CKD.

Our study has several limitations that mainly arise from its retrospective design. First, this retrospective study conducted in a large-sized referral center has an inherent limitation of selection bias. The rate of bleeding from GAVE could have been overestimated because patients who were referred to our emergency department presenting with bleeding symptoms were included in the study. Second, the endoscopists at our center shared their therapeutic strategy for endoscopic treatment, and APC was chosen for endoscopic hemostasis in most of the cases (94%), while other modalities of endoscopic treatment, such as cryotherapy, EBL, and RFA, were not performed. Thus, outcomes of the bleeding group may be different with other endoscopic procedures. Third, in terms of APC for bleeding control, the number of procedures and the extent of APC application were made at the discretion of each endoscopist. Differences in the strategies of APC may have contributed to the outcomes of the bleeding group. Despite these limitations, this study describes the clinical course of GAVE by analyzing the largest sample size reported to date.

In conclusion, we found that in patients with GAVE, Child–Pugh class B or C liver cirrhosis, CKD, use of antithrombotic agents, and involvement of the duodenal bulb were associated with high risks for GI bleeding from GAVE. A careful follow-up is necessary in patients with these factors.

KEY MESSAGE

1. A careful follow-up for bleeding is needed in gastric antral vascular ectasia patients with liver cirrhosis, chronic kidney disease, use of antithrombotic agents, and duodenal bulb involvement.

2. Chronic kidney disease was significantly associated with rebleeding.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Sung Hyun Cho: investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft; Jinyoung Kim: investigation, data curation, formal analysis; Hee Kyong Na: conceptualization, resources, data curation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision; Ji Yong Ahn: conceptualization, data curation, writing - review & editing, supervision; Jeong Hoon Lee: resources, writing - review & editing; Kee Wook Jung: resources, writing - review & editing; Do Hoon Kim: resources, writing - review & editing; Kee Don Choi: resources, writing - review & editing; Ho June Song: resources, writing - review & editing; Gin Hyug Lee: resources, writing - review & editing; Hwoon-Yong Jung: resources, writing - review & editing

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None