The effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication and development of immune-mediated disorder in children: a nationwide population-based study in Korea

Article information

Abstract

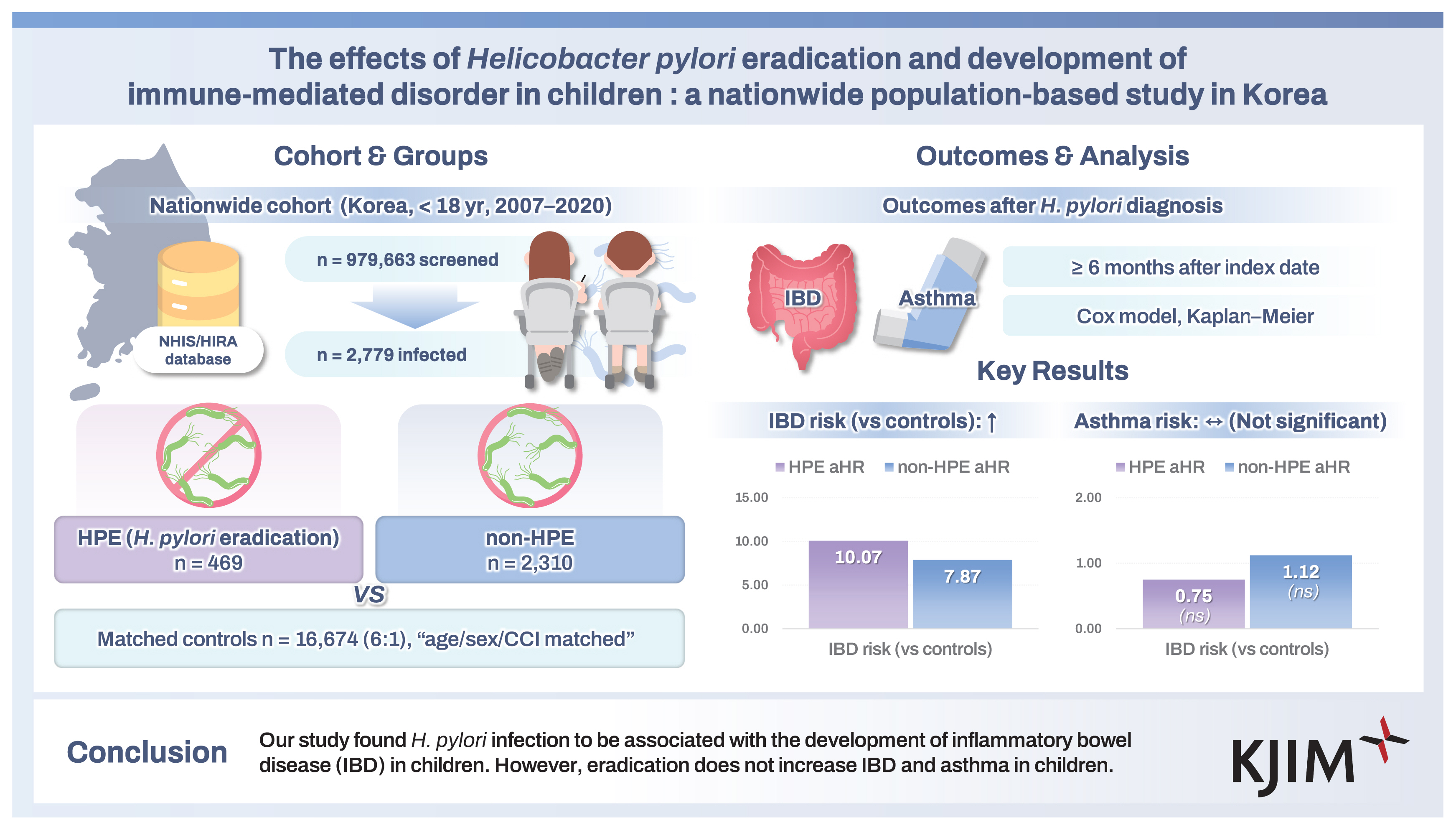

Background/Aims

Helicobacter pylori may protect against immune-mediated disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and asthma. This study evaluated whether eradication was associated with IBD and asthma in Korean children.

Methods

Data were collected from the Korean National Health Insurance information on patients younger than 18 years and without a prior diagnosis of IBD or asthma from January 2007 to September 2020. Patients confirmed with H. pylori infection were divided into the eradication and non-eradication group. We compared the incidence of IBD and asthma in infected patients with an age, and sex-matched control group.

Results

In total, 979,663 patients were selected based on the inclusion criteria and 2,779 patients were included based on the exclusion criteria. The occurrence of IBD in infected patients was statistically significant (p < 0.05) but there was no association of infection with asthma. There was no association with eradication and the development of IBD and asthma. The infected group had a shorter duration till diagnosis of IBD than the control group.

Conclusions

Our study found H. pylori infection to be associated with the development of IBD in children. However, eradication does not increase IBD and asthma in children.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that [1,2] is observed in half of the world’s population. 10–15% of those infected develop peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and 3% develop gastric cancer [3]. The diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for H. pylori in pediatric patients differ from those in the corresponding adults [4]. Recent guidelines report that H. pylori always induces gastritis, and eradication is recommended in areas with a high risk of gastric cancer [5,6]. However, the eradication of H. pylori in asymptomatic children is controversial and must be individualized [7]. Recent pediatric guidelines recommend that eradication should be performed only after endoscopic diagnosis in patients with symptoms related to H. pylori infection [8].

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an immunological disorder with a diverse and multifactorial etiologies, including host genetic and immunological factors, environmental factors, and microbiota. Various immune cells, such as T lymphocytes, are involved in the pathogenesis of IBD. In general, T helper 1 (Th1) cells mediate the immunological reactions related to infection, while T helper 2 (Th2) cells induce the production of cytokines that mediate allergic reactions [9,10]. The imbalance between these two immune responses plays a vital role in the development of IBD and allergic diseases. H. pylori infection activates the T cell-mediated pathways. Recent studies have reported that H. pylori increases the expression of regulatory T cells, which may prevent the development of IBD [11]. Other studies have reported that H. pylori induces a strong Th1 response and is associated with the development of allergy [12–18].

Asthma is also an immunological disorder of the respiratory tract, which is one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases in children, and its incidence and associated mortality rates have increased recently [19]. Although several studies have reported an inverse correlation between asthma and H. pylori infection, there have been no reports on the prevalence of asthma after H. pylori eradication [12,17,20–24]. Similarly, the prevalence of IBD has also increased in recent years, but there is limited research on the role of H. pylori eradication in the onset of IBD [25]. Therefore, we examined whether H. pylori infection and eradication were associated with the incidence of autoimmune diseases such as IBD and asthma using nationwide cohort data.

METHODS

Database

Data were extracted from the publicly available Healthcare Bigdata Hub of the Health Insurance Review & Assessement Service (HIRA) provided by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS). The NHIS is a national single insurer that covers the entire population of Korea, and this dataset includes information on demographics, diagnoses, medications, procedures, medical costs, and mortality of patients. Diagnoses were coded according to the International Classification of Disease – 10th revision. Data were extracted using the following research methods.

Study design

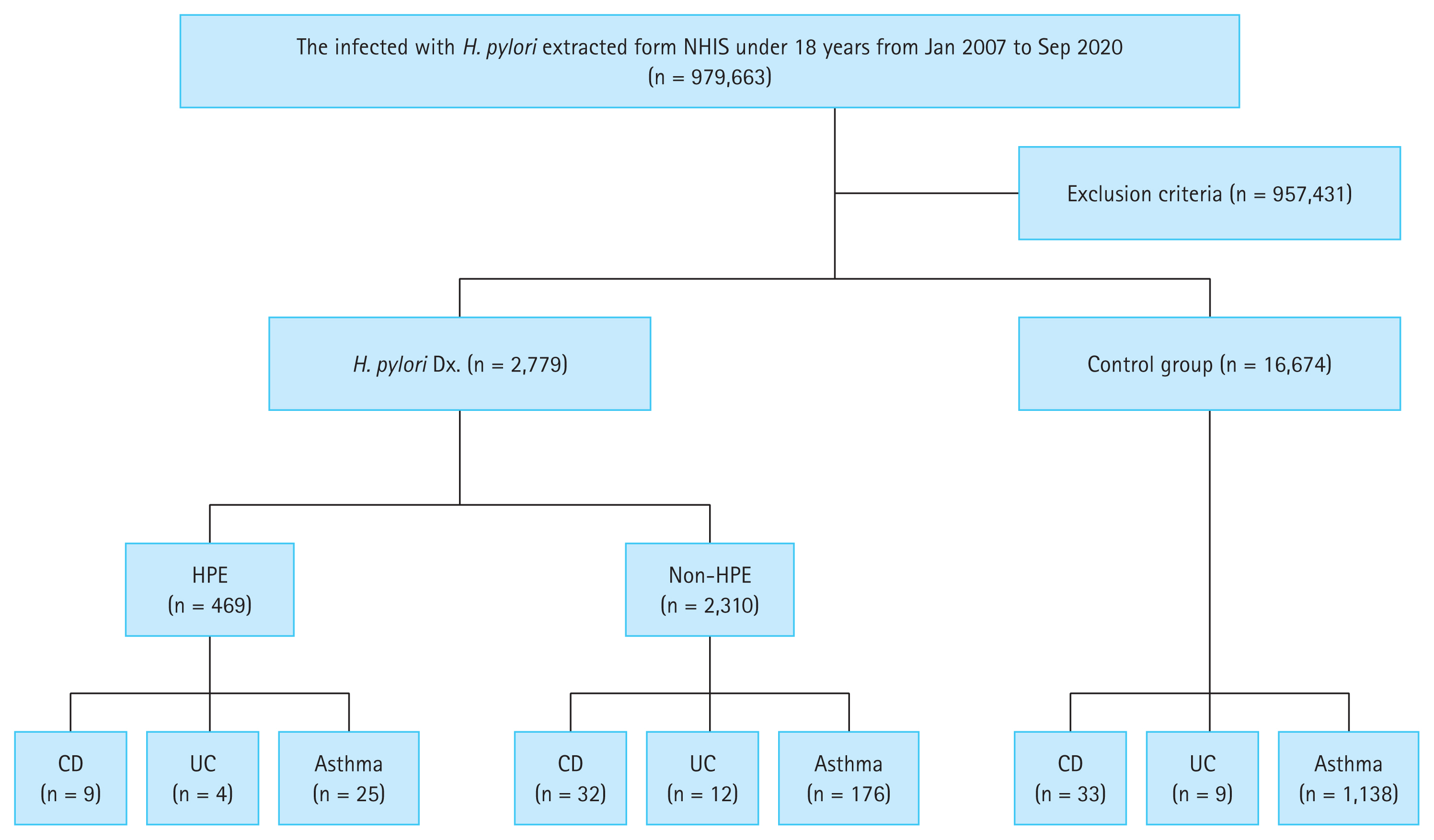

Patients who were younger than 18 years and diagnosed with H. pylori were selected from January 2007 to September 2020. Those who had only an allergic disease other than asthma, or who had been diagnosed with IBD or asthma before the diagnosis of H. pylori were excluded. These patients were divided into the H. pylori eradication group (HPE) and the non-H. pylori eradication group (non-HPE). Patients diagnosed with IBD, including Crohn’s disease (CD) or ulcerative colitis (UC), as well as asthma, after the diagnosis of H. pylori infection were examined. The period between the diagnosis of H. pylori and the diagnosis of these autoimmune diseases was examined. The control group comprised six times the number of patients with H. pylori infection (Fig. 1).

Definition of subjects

Patients with H. pylori infection were defined by a diagnosis code of H. pylori and if the patient received a laboratory test or endoscopic procedure prior to diagnosis. Laboratory tests included antibody test, stool antigen test, and urease breath tests, whereas endoscopic procedures included War-thin–Starry silver staining, urease test, and cultures. The HPE group consisted of patients prescribed a standard triple or bismuth quadruple therapy regimen. The non-HPE group comprised patients who did not prescribed with either therapy. Standard triple therapy consisted of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), amoxicillin (AMO) and either clarithromycin (CLA) or metronidazole (MET). Bismuth quadruple therapy consisted of PPI, AMO, CAL or MET and bismuth.

To confirm eradication therapy, the presence of diagnostic codes for stool antigen test, urea breath test, H. pylori polymerase chain reaction, urease test, and Giemsa staining were used as evidence for confirmation testing. These tests were required to have occurred at least 21 days after the eradication therapy. Successful eradication was defined as the presence of a confirmation test within six months after the eradication therapy and the absence of a second eradication therapy within one year.

Asthma was defined as the presence of at least one of the following prescriptions for at least 3 months, along with a diagnosis code for asthma; 1) inhalants such as ciclesonide, fluticasone, budesonide, 2) leukotriene receptor antagonist, 3) long acting β2-adrenergic agonist, and 4) anti-immunoglobulin E. CD and UC are legally classified and managed as rare intractable diseases in Korea and diagnosis is managed and supervised by the NHIS. Therefore, diagnostic code alone were deemed to be sufficient for the diagnosis of these two diseases [26]. Patients with allergic diseases other than asthma such as allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis were excluded. In addition, patients with IBD or asthma before H. pylori diagnosis were also excluded. Diagnosis of IBD and asthma were defined as cases diagnosed at least six months after the definition of H. pylori infection.

The control group was matched for age, sex, and Charlson’s comorbidity index score with the case group and was six folds the size of the case group. To exclude the impact of antimicrobial therapy on the development of autoimmune diseases, we defined the control group as patients with prescription codes for AMO, MET, or CLA for more than 1 week. In order to exclude diagnoses that could influence the development of IBD and asthma, the control group consisted of patients who were prescribed antibiotics for diseases such as dental caries, cellulitis or chronic sinusitis, mycoplasma pneumonia, or skin infections. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Incheon St. Mary’s hospital (No. OC21ZISI0039).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (range) and were analyzed using the Student t-test or Mann–Whitney test. Categorical variables are described as numbers (%) and were analyzed using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test. The cumulative events of asthma, CD, and UC were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier curve and analyzed using the log-rank test. The relative risks of IBD and asthma after H. pylori eradication were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression analysis, and are presented as adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) with 95% confidence intervals. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

RESULTS

Basic characteristics

The total number of patients treated from January 2007 to September 2020 was 2,779. Patients with H. pylori infection (n = 2,779) were classified into HPE (n = 469) and non-HPE (n = 2,310) groups. The control group consisted of 16,674 individuals who matched the patients with H. pylori infection in terms of age, sex, and Charlson’s comorbidity index score (Fig. 1).

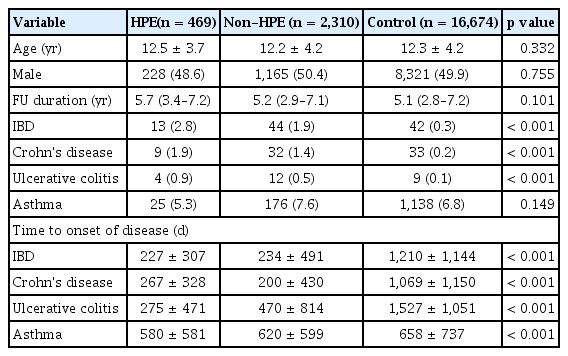

The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. In the HPE group, the average age was 12.5 ± 3.7 years and 48.6% (n = 228) of the patients were male. In the non-HPE group, the average age was 12.2 ± 4.2 years, and 50.4% (n = 1,165) were male. In the control group, the average age was 12.3 ± 4.2 years, and 49.9% (n = 8,321) were male. The median follow-up duration was 5.7, 5.2, and 5.1 years in the HPE, non-HPE, and control groups, respectively (Table 1).

Development of IBD and asthma related to H. pylori infection

The prevalence of IBD in the HPE, non-HPE and control groups were 2.8%, 1.9%, and 0.3%, respectively. The prevalence rate of CD were 1.9%, 1.4%, and 0.2%, respectively. The prevalence rates of UC in each group were 0.9%, 0.5%, and 0.1%, respectively (p < 0.001). The prevalence of asthma was 5.3%, 7.6%, and 6.8%, respectively (p = 0.149). The HPE group exhibited a shorter duration form the diagnosis of H. pylori to the onset of IBD compared to the control group. This duration was also decreased in the HPE group compared with that in the control group in the context of asthma (Table 1).

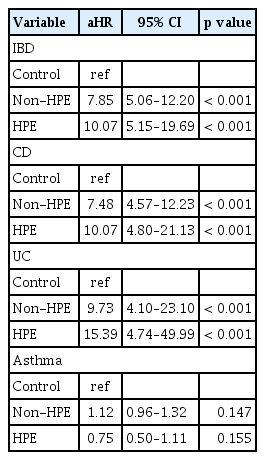

Risk of IBD and asthma after eradication of H. pylori

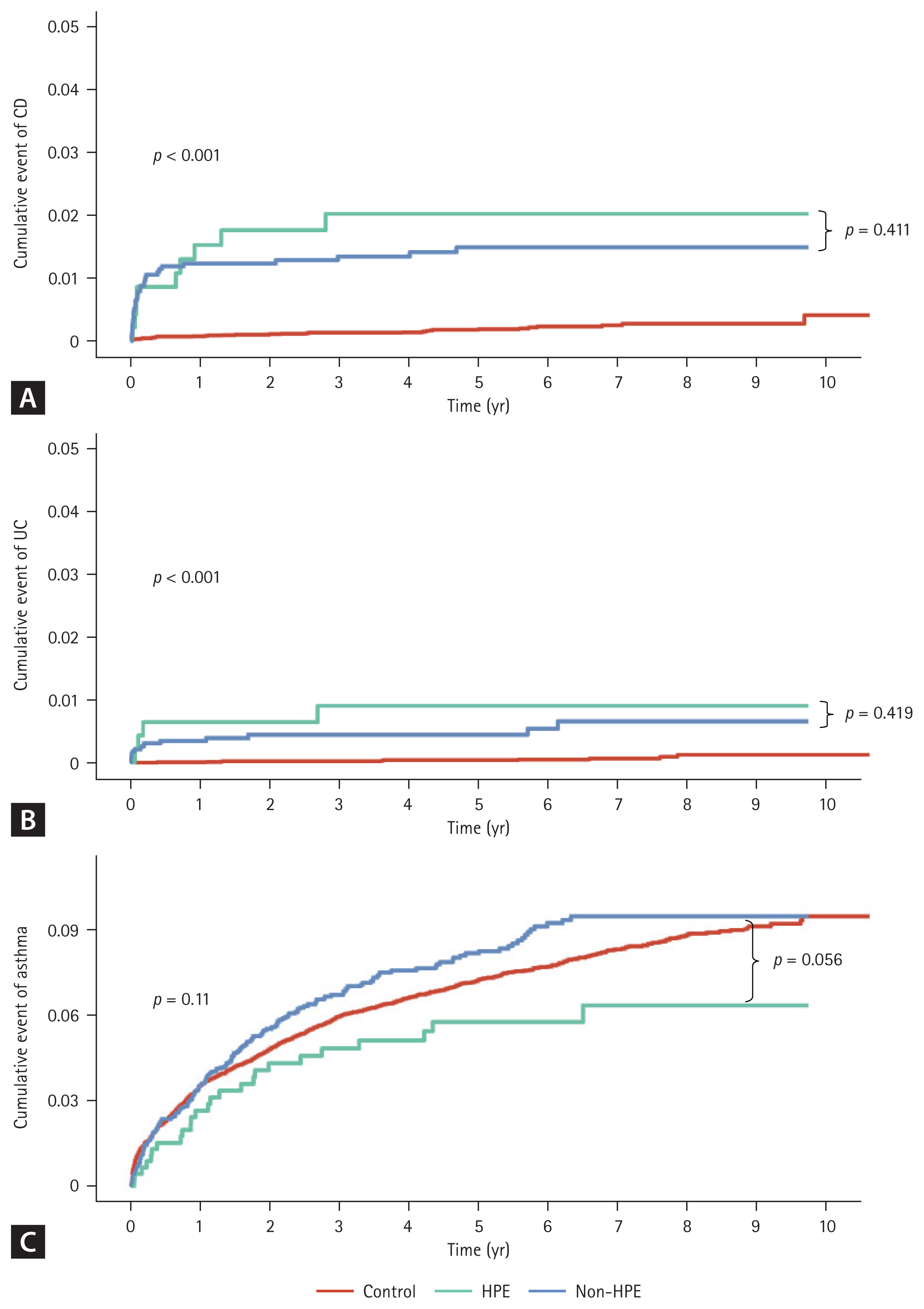

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of eradication on the occurrence of IBD and asthma (Table 2). The aHR for IBD in the HPE and non-HPE group were 10.07 and 7.85, respectively. The aHR for CD in the HPE and non-HPE group were 10.07 and 7.48, respectively. The aHR for UC in the HPE and non-HPE groups were 15.39 and 9.73, respectively. However, aHR did not show a statistically significant difference in asthma. Eradication of H. pylori itself did not increase the risk of developing CD or UC (Fig. 2A, B). There were no statistically significant differences in H. pylori infection or eradication in patients with asthma (Fig. 2C).

Cumulative event rate of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and asthma in Helicobacter pylori infection, eradication and control group. Kaplan–Meier plots estimated the cumulative event of IBD and asthma, and the log-rank test was used for analysis. (A) Crohn’s disease. (B) Ulcerative colitis. (C) Asthma. HPE, Helicobacter pylori eradication.

Comparison of IBD and asthma onset according to period after H. pylori eradication

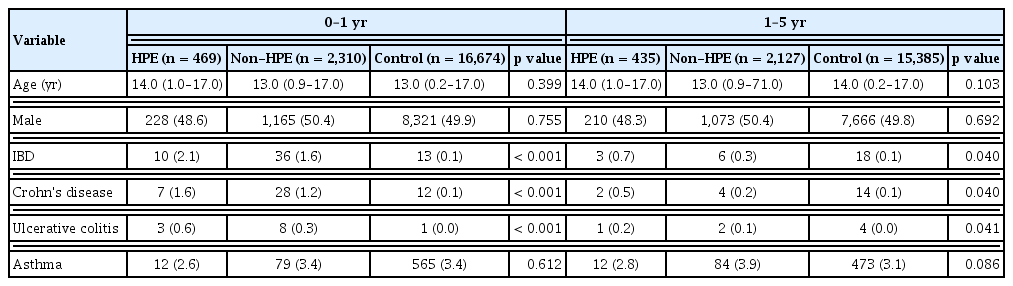

We examined the duration utill diagnosis of IBD and asthma after H. pylori eradication (Table 3). Most cases of IBD occurred within 5 years after the diagnosis of H. pylori, the diagnosis of CD occurred within 5 years after diagnosis of H. pylori in all cases. The diagnosis of UC occurred after 5 years in two cases and within 5 years in 14 cases. In the HPE group, 7 (77.8%) patients were diagnosed with CD within 1 year, and 2 (22.2%) were diagnosed after 1 year. Three (75.0%) patients were diagnosed with UC within 1 year and one (25.0%) patient was diagnosed after 1 year. No statistically significant differences were observed in the time from H. pylori diagnosis to onset of IBD between the HPE and non-HPE groups.

Comparison of prevalence and characteristics according to the period after Helicobacter pylori infection

Twelve (48.0%) patients were diagnosed with asthma within one year and 13 (52.0%) were diagnosed after one year in the HPE group. In the non-HPE group, 79 cases (44.9%) were diagnosed within one year, and 84 cases (55.1%) were diagnosed after one years. No statistically significant differences were observed in the time from H. pylori diagnosis to onset of asthma between the HPE and non-HPE groups.

DISCUSSION

This study examined whether H. pylori infection and eradication are associated with immunological disorders such as IBD and asthma in children. Several recent studies have reported that H. pylori infection may have a protective role in the development of immunological diseases [12,13,22,27,28]. However, few studies have examined whether eradication is associated with immunological disease in children [25,29]. To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine whether eradication is associated with IBD and asthma in pediatric patients. We found that IBD was increased in H. pylori-infected patients, but eradication did not increase the risk of IBD. Meanwhile, asthma was not associated with H. pylori infection or eradication.

In our study, only the presence of H. pylori infection, and not eradication, was shown to increase the new onset of both CD and UC. However, recent studies have mainly stated that H. pylori infection has a protective effect against IBD [29–31]. In addition, the prevalence of H. pylori infection has decreased significantly in Korea from 10.8% in 2008 to 6.5% in 2014 [32,33]. Meanwhile, the prevalence of IBD in children in Korea is increasing [34]. The reduction in the prevalence of H. pylori is commonly attributed to the hygiene hypothesis. Although the incidence of IBD has increased, this increase cannot be solely attributed to the decline in H. pylori infection. Instead, environmental factors, such as adoption of Westernized diets, may contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD. This study, however, concluded that H. pylori infection might increase the risk of developing IBD, which could be explained by several mechanisms. First, from an immunological perspective, H. pylori infection induces the production of neutrophil activating proteins, which trigger Th1 activation. Given that Th1 cells play a crucial role in IBD pathogenesis, this pathway may contribute to the development of IBD. Second, recent pediatric studies have reported that H. pylori infection exacerbates dysbiosis [35], which is a key factor in IBD pathogenesis. Since H. pylori infection can independently cause dysbiosis, it may act as a risk factor for IBD. Another possible reason for this result is that endoscopies were performed when patients had gastrointestinal symptoms, which could lead to the confirmation of H. pylori infection. Most cases of IBD occurred within five years after the diagnosis of H. pylori. Therefore, symptomatic patients in the preclinical stage of IBD may be diagnosed with H. pylori infection.

In asthma, most studies have reported that H. pylori infection exerts protective effects through not only innate immune cells but also adaptive immunity, but in this study, H. pylori infection showed no significant association with developing asthma, and eradication of H. pylori did not increase the risk. The peak incidence of asthma in children typically occurs between 5 and 14 years of age [36]. However, in this study, the mean age at the diagnosis of H. pylori infection was 12 years. Since the development of asthma was evaluated after the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, it may be challenging to fully assess the impact of H. pylori infection on pediatric asthma.

This study found that H. pylori infection increases the risk of IBD, but is not associated with asthma. This difference may arise from the fact that gastrointestinal tract is the primary site of H. pylori infection, making its impact on intestinal diseases such as IBD more significant than respiratory tract disorders such as asthma. However, many recent studies have reported an inverse correlation between H. pylori infection and both IBD and asthma, emphasizing the need for further investigation of the underlying mechanisms.

It is also important to consider that the clinical manifestations of H. pylori infections differ between children and adults. In adults, H. pylori infection is primarily associated with PUD and gastric cancer, whereas pediatric infections are often asymptomatic. Symptomatic infections in children are more commonly observed when they develop later in life. One recent adult study reported that H. pylori eradication increased the risk of autoimmune diseases, including IBD [25], and our findings similarly suggest that eradication might elevate the risk in pediatric populations. Regarding asthma, early exposure to H. pylori in children has been reported to have a protective effect [24], whereas in adults, some studies have suggested that H. pylori infection may increase the prevalence of asthma [37]. These discrepancies may reflect differences in immune responses, as pediatric immune systems are still maturing, leading to distinct immunological reactions compared to those in adults.

This study had several limitations. Our study is based on public claims data, and the inherent limitations of such studies are also presented. Diagnosis and prescription of procedures and medications were based on diagnostic codes. However, we believe that the diagnosis of H. pylori infection and IBD is correct, as it is based on objective examinations. In addition, the diagnosis of IBD is regulated by the Korean NHIS. It is also the possible that the control group included asymptomatic patients with H. pylori infection. Moreover, subtype classification, such as IBD-unclassified, is an important subtype in children, and may not have independent diagnostic codes in the database, posing limitations for subtype analysis. Laboratory findings, such as test results for asthma-related strains of H. pylori, were not available in the databases, as only information about whether the test was performed was recorded. Finally, we could not investigate whether the eradication effects differed between male and female children. Despite these limitations, this study is significant as it is a large-scale investigation of the impact of H. pylori infection and eradication on the development of IBD and asthma in pediatric patients.

In conclusion, we found that H. pylori infection is positively correlated with the developing IBD, but eradication has no relation with IBD occurrence. The diagnosis of IBD was made within the first year of H. pylori infection, suggesting that symptomatic patients were investigated and diagnosed more often in H. pylori infected patients. There was no relationship between H. pylori infection and eradication with asthma. Therefore, this study suggests that the eradication of H. pylori itself does not increase the development of IBD and asthma in children. Further prospective studies are needed to evaluate the correlation between H. pylori infection and autoimmune disease.

KEY MESSAGE

1. H. pylori infection has been associated with a risk of IBD in children.

2. Our nationwide study found that H. pylori eradication itself does not increase the development of IBD and asthma in children.

Notes

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jinseob Kim (Zarathu Co., Ltd, Seoul, Republic of Korea) for statistical advice.

CRedit authorship contributions

You Ie Kim: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing - original draft; Joon Sung Kim: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, writing - review & editing, supervision; Sang Yong Kim: conceptualization, resources, data curation, validation; Byung-Wook Kim: conceptualization, resources, data curation, validation

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None