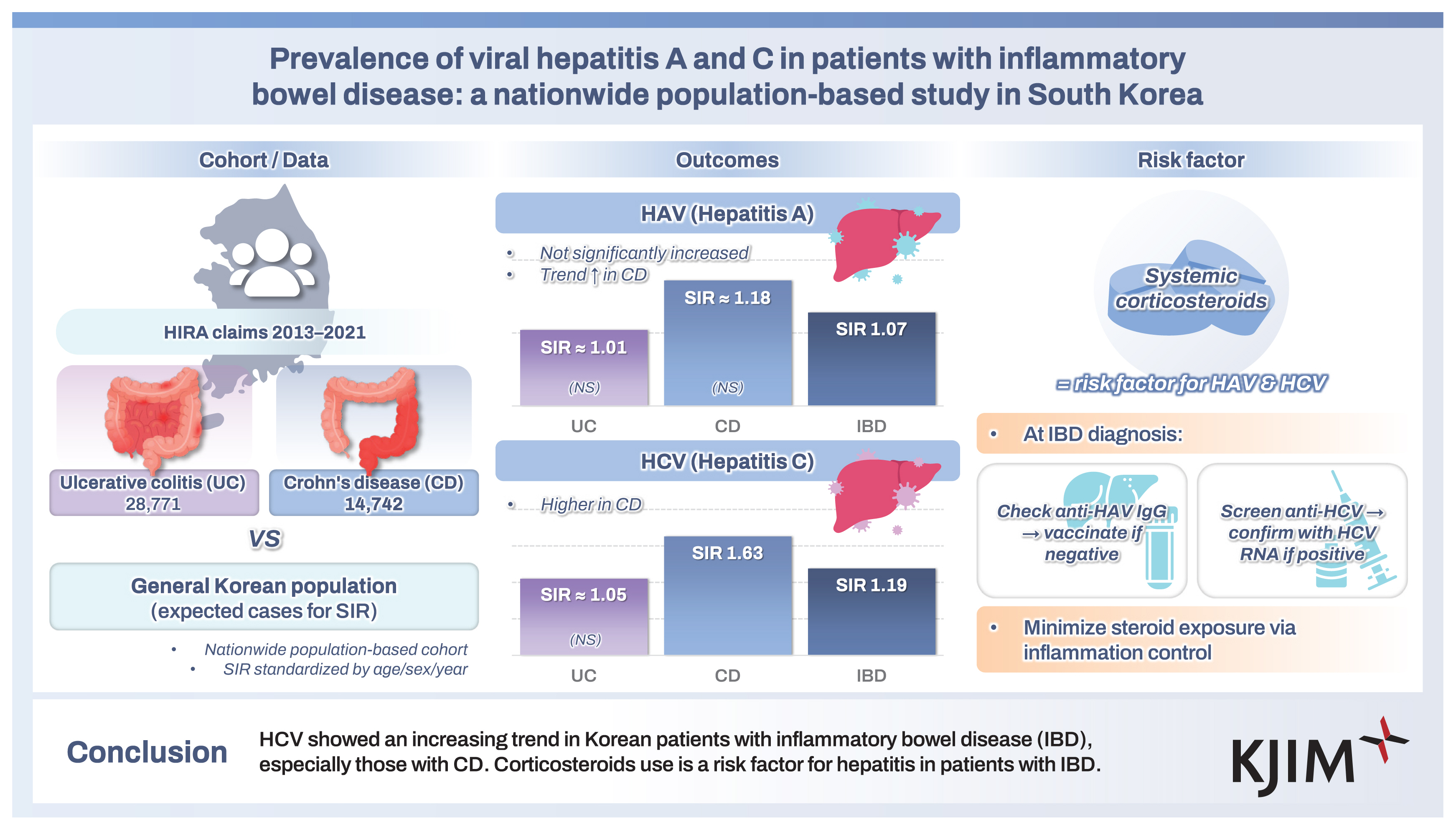

Prevalence of viral hepatitis A and C in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide population-based study in South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

We investigated whether patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Korea have an increased risk of hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections and sought to identify the risk factors for these infections.

Methods

We performed a nationwide population-based study using 2013–2021 data from the Korean National Health Insurance Claims Database. We calculated the incidence rates and standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) of HAV and HCV infections in patients with IBD compared with the overall Korean population.

Results

A total of 43,513 patients were included in this study. A total of 317 cases of HAV were identified in 276,007 person-years, while 297 cases of HAV developed in the Korean general population. The SIR of HAV in the patients with IBD was 1.07 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.96–1.19) and the increase of HAV infection in patients with IBD was not statistically significant. A total of 289 cases of HCV infection were identified in 276,538 person-years, while 242 cases of HCV infection developed in the Korean general population. The SIR of HCV in patients with IBD was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.06–1.34) and the increase of HCV infection in patients with Crohn’s disease (SIR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.31–2.04). Corticosteroid use was identified as a risk factor for HAV and HCV infections in patients with IBD.

Conclusions

HCV showed an increasing trend in Korean patients with IBD, especially those with Crohn’s disease. Corticosteroids use is a risk factor for hepatitis in patients with IBD.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects the digestive tract and is divided into ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). With the increasing incidence worldwide [1,2], the treatment of IBD has been revolutionized over the past decade with the increasing use of immunomodulators and biologic agents. Due to the increased use of drugs related to the immune response, the risk of opportunistic infections caused by bacteria or viruses also increases [3]. The risk of developing hepatitis may increase in patients with long-term IBD due to the increased frequency of procedures with a risk of infection, such as endoscopy, blood transfusion, and surgery [4,5].

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) can be transmitted via the fecal- oral route through contaminated water or food. In Korea, less than 10% of young people under 30 have immunity to HAV, as exposure to HAV has decreased due to social and economic development and improved hygiene standards [6]. There have been no studies on the incidence of HAV in patients with IBD. Although patients with IBD are not considered a high-risk group, acute HAV infection can be severe or even fatal. In particular, there is a high risk of fulminant liver failure when HAV infection occurs in immunocompromised patients [7].

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) leads to chronic hepatitis in 70% of patients infected with the virus, and according to 2015 data, approximately 1% of patients worldwide are chronic HCV patients [8]. In Korea, according to a 2020 study, 0.7% of the total population tested positive for HCV antibodies, showing an increasing trend with age [9]. However, with the recent rapid development of HCV treatment, the rate of chronic HCV infection is decreasing. Because infection can occur through blood, syringes, or sexual intercourse [10], the incidence of HCV may increase in patients with IBD. There have been several studies on the incidence of HCV infection in patients with IBD, but the results have been conflicting. In addition to its incidence, it is important to consider the presence of IBD when treating HCV, because interactions may occur between HCV and IBD drugs, which may increase drug toxicity or reduce drug efficacy [11].

Many studies have reported on the onset and reactivation of hepatitis B, but there are few studies on HAV, and the results regarding HCV infection have differed between studies. Accordingly, this study aimed to determine the incidence of HAV and HCV in patients with IBD compared to the general population and to suggest appropriate management.

METHODS

Data source

This study used data from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRAS). The HIRAS reviews all health insurance claims from Korean hospitals and clinics, including claims submitted under the National Health Insurance (NHI) system and medical benefit program, which covers 97.2% of the entire population of Korea. Approximately 46 million claims are filed annually nationwide, including claims from more than 80,000 healthcare facilities. The Korean government launched rare intractable disease (RID) registration program in 2006 within the NHI system, which provides co-payment relief for medical expenses related to 167 RIDs, including UC and CD [12]. Accordingly, patients must have their diagnosis certified by a physician using established diagnostic criteria provided by the NHI and must then undergo review by the relevant medical institution and the NHI. Therefore, data on RIDs in Korea can be considered reliable [12]. After registration, all RID-related claims will include a specific code assigned to each RID, in addition to the diagnosis code [12].

Study design

This retrospective cohort study used data from January 2013 to December 2021, as requested by the HIRAS. The requirement for informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Patient selection and ascertainment of hepatitis

Patients with IBD must (1) have a disease code of UC (K51.0–51.9) or CD (K50.0–50.9) as a primary or secondary diagnosis, (2) have a prescription for IBD-related medication, and (3) meet both RID registrations for UC (V131) or CD (V130).

Prescriptions for IBD-related medications include at least two times prescription of oral or topical 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) drugs, steroids, thiopurines (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine), or anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents (infliximab or adalimumab). As systemic corticosteroids may be widely used for other indications, we did not include patients who were prescribed only systemic corticosteroids. Patients whose diagnosis changed from UC to CD or vice versa during the study period and who had concurrent diagnosis codes for UC and CD were excluded from the study population because they could not be classified correctly [13,14].

HAV was defined as a patient meeting one of the following diagnostic codes: hepatitis A with hepatic coma (B15.0) or without hepatic coma (B15.9). HCV was defined as a patient meeting one of the following diagnostic codes: acute hepatitis C (B17.1) or chronic hepatitis C (B18.2).

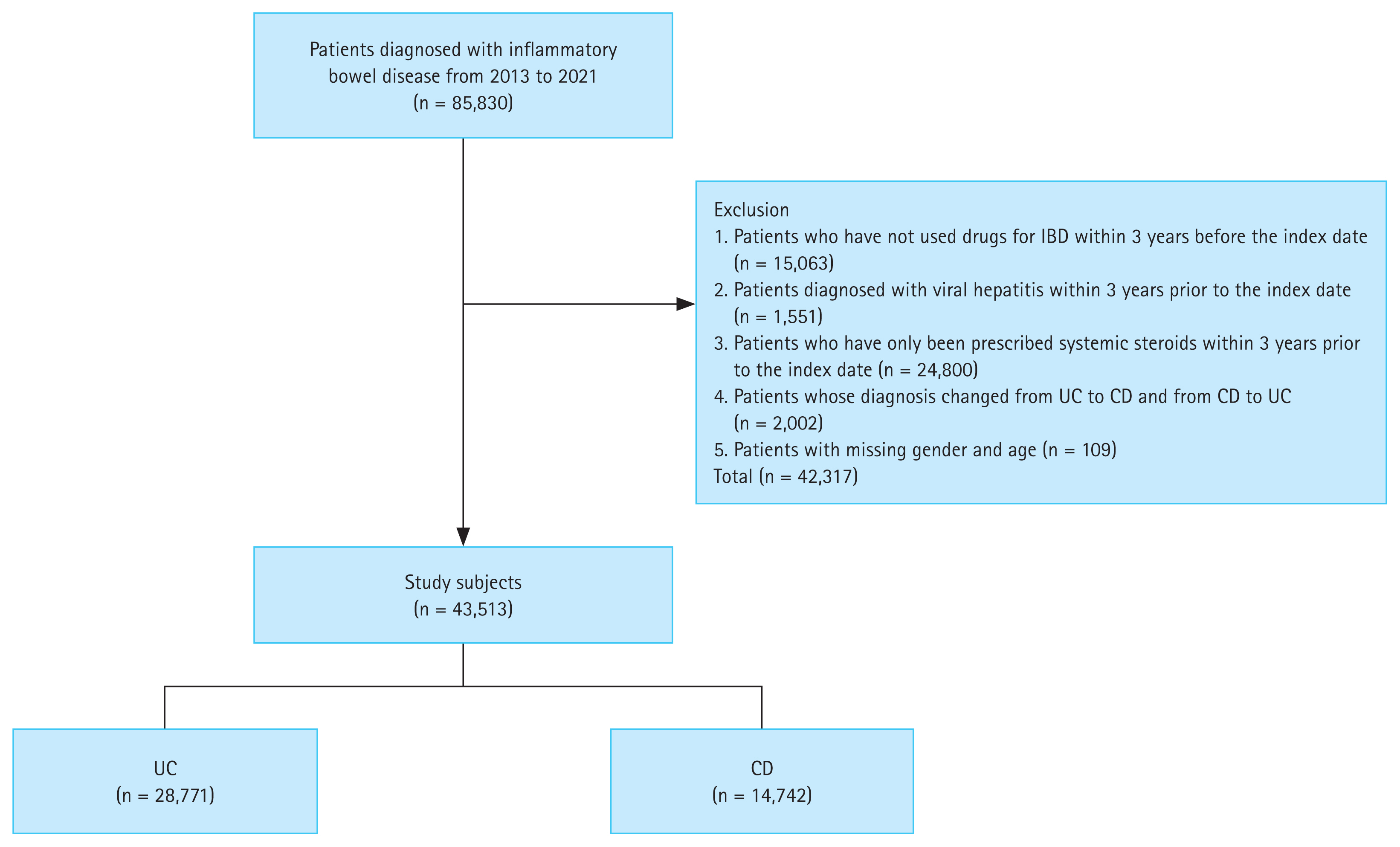

Study population

A total of 85,830 patients diagnosed with IBD (UC or CD) were enrolled between 2013 and 2021. We excluded patients who were prescribed only systemic corticosteroids, patients who had no history of prescriptions for IBD-related medications, patients whose diagnosis changed from UC to CD or vice versa, patients who had simultaneous diagnosis codes for UC and CD, and patients who were with viral hepatitis within 3 years prior to the index date. Patients with missing sex or age data were also excluded. A total of 43,513 patients, including 28,771 with UC and 14,742 with CD, were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the incidence of hepatitis (per 1,000 person-years) in Korean patients with IBD and the overall Korean population, assuming a Poisson distribution. We used the standardized incidence ratio (SIR) to investigate whether the incidence of hepatitis was higher in patients with IBD than in the general population. SIR was calculated as the ratio of the observed number of hepatitis cases to the expected number of hepatitis cases for the general population stratified by 10 years of age, sex, and year in Korea. In Korea, a national infectious disease surveillance system is implemented based on Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act. This system allows us to determine the incidence of each infectious disease based on reported cases. Hepatitis A is classified as a Group 2 infectious disease in Korea, and hepatitis C is classified as a Group 3 infectious disease. Using this system, we calculated the expected number of hepatitis cases and determined the SIR. The confidence intervals (CIs) of SIR were estimated assuming a Poisson distribution.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide software version 6.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hanyang University Hospital (HYUH 2023-05-047).

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients

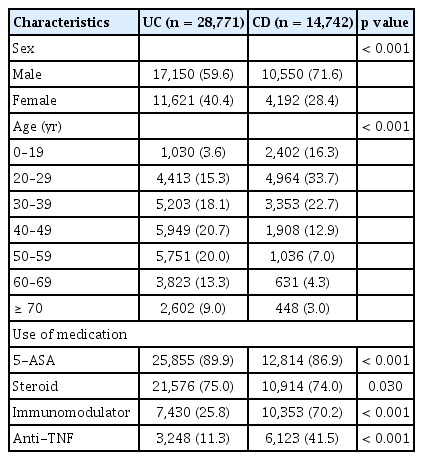

The characteristics of the 43,513 patients with IBD (2013–2021) comprising 28,771 patients with UC and 14,742 patients with CD are reported in Table 1. The proportion of men was significantly higher in patients with CD than in those with UC, while age was significantly lower in patients with CD. Patients with UC had a higher rate of 5-ASA use than those with CD, whereas patients with CD had a higher rate of thiopurine and anti-TNF use than those with UC.

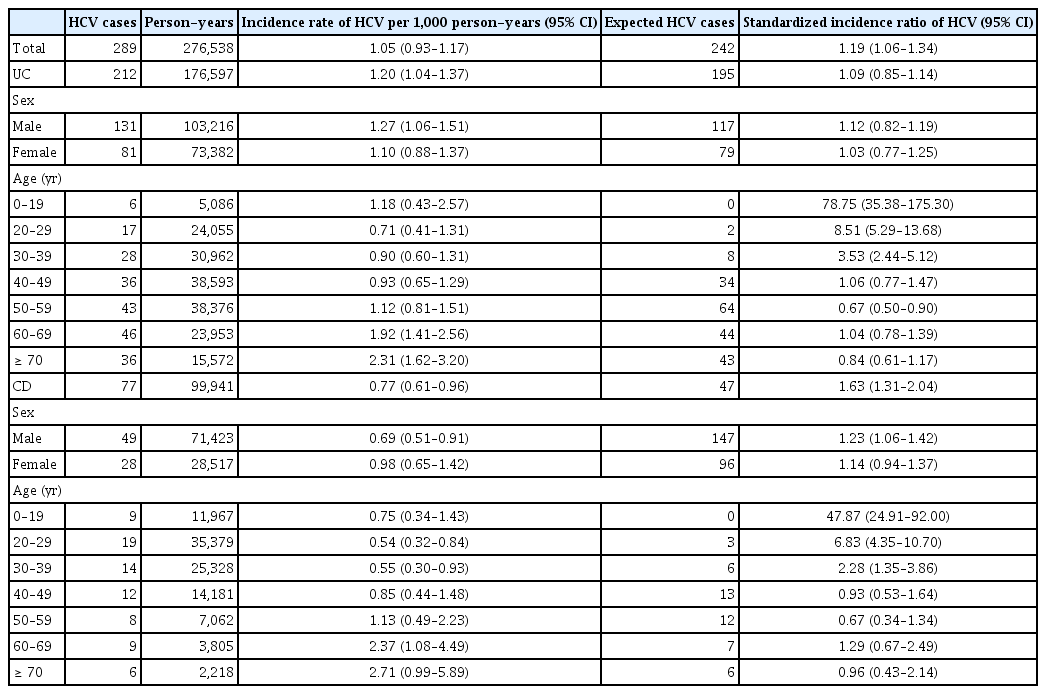

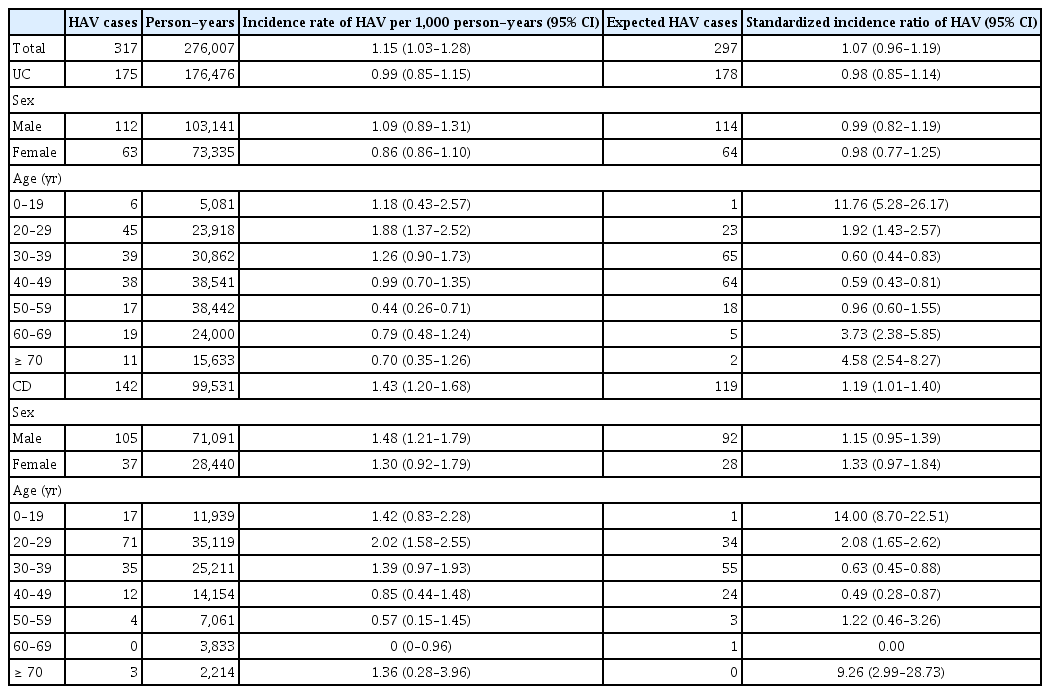

Incidence of HAV in patients with IBD

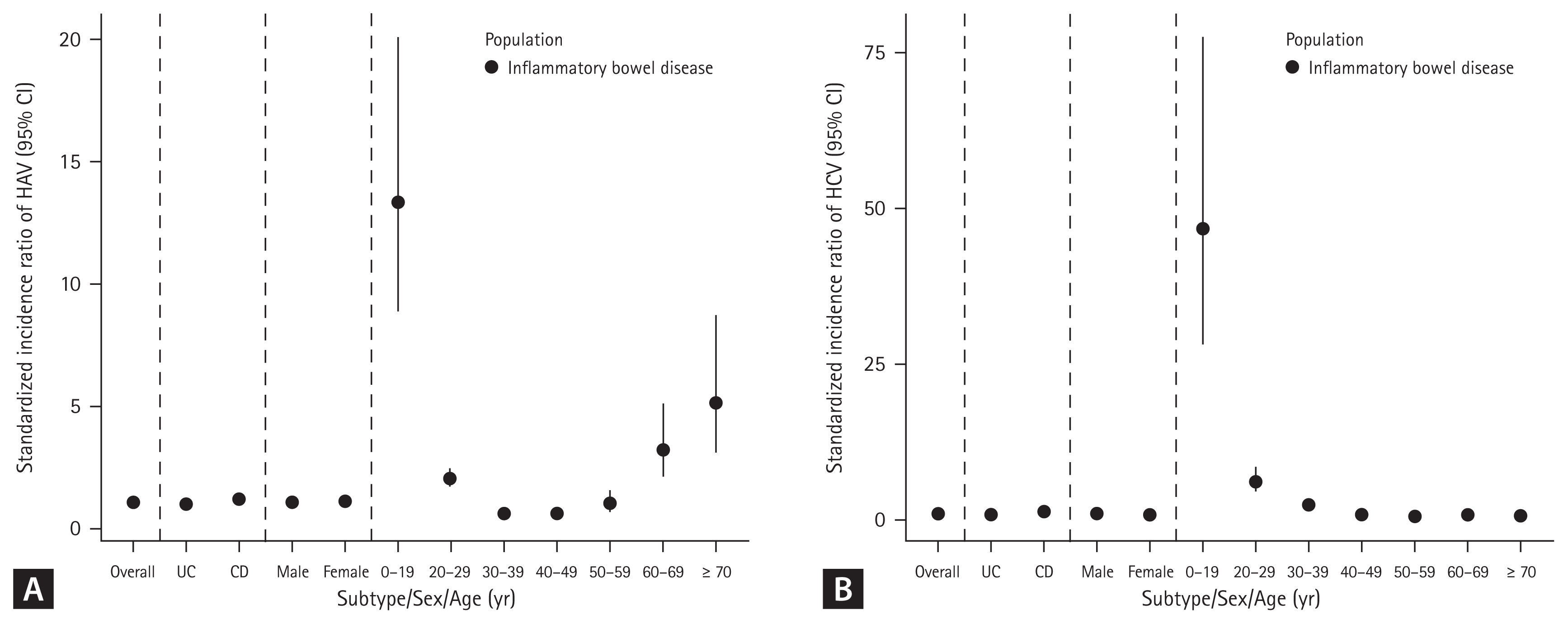

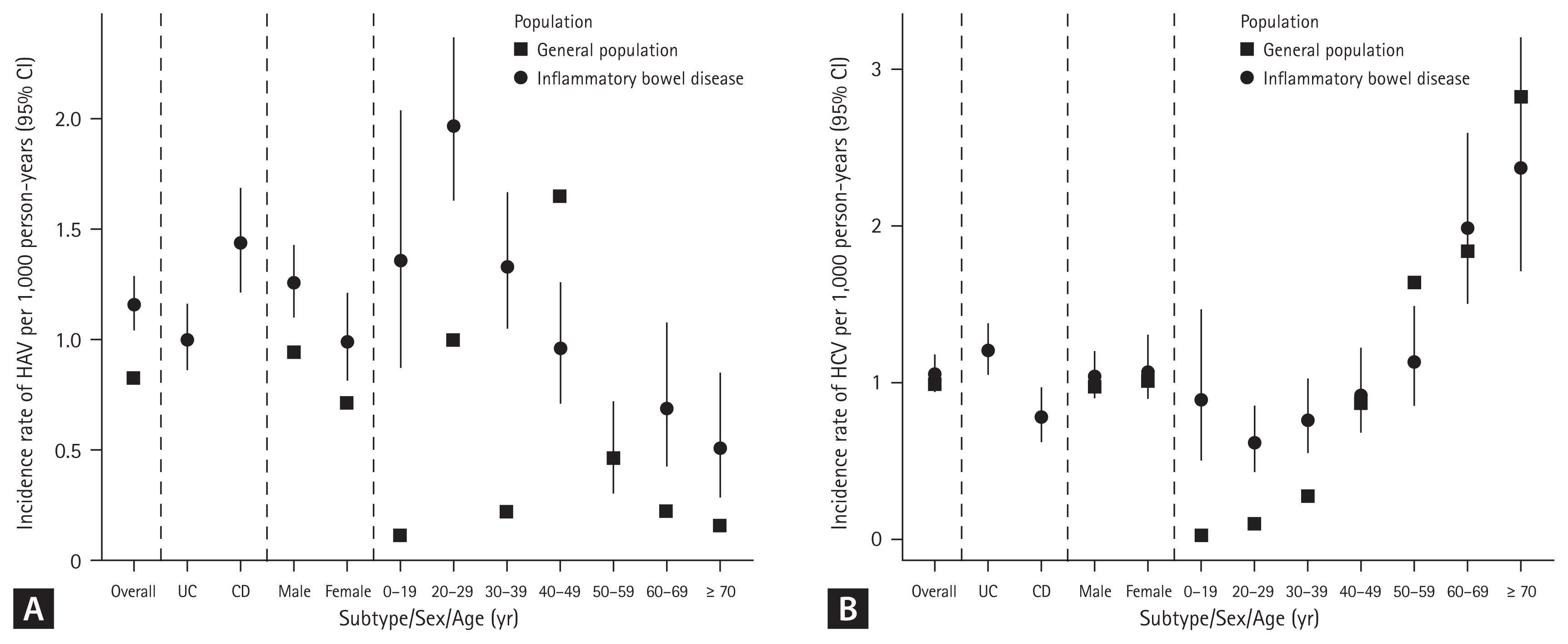

A total of 317 cases of HAV were identified during 276,007 person-years (incidence rate [IR], 1.15/1,000 person-years; 95% CI, 1.03–1.28), while 297 cases of HAV developed in the Korean general population. The SIR of HAV in patients with IBD was 1.07 (95% CI, 0.96–1.19) (Table 2). In patients with UC, 175 cases of HAV were identified over 176,476 person-years (IR, 0.99/1,000 person-years; 95% CI, 0.85–1.15), while 178 cases of HAV developed in the Korean general population. The SIR of HAV in the patients with UC was 0.98 (95% CI, 0.85–1.14). In patients with CD, 142 cases of HAV were identified over 99,531 person-years (IR, 1.43/1,000 person-years; 95% CI, 1.20–1.68), while 119 cases of HAV developed in the Korean general population. The SIR of HAV in patients with CD was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.01–1.40) (Table 2, Fig. 2A, 3A). There was a tendency for the HAV IR to increase in patients with IBD under 29 years of age and over 60 years of age; however, there was no difference in the HAV IR between patients with IBD and the general population among those aged 30–59 years. Overall, the incidence of HAV did not increase in patients with IBD; however, an increasing trend was confirmed in patients with CD.

Incidence rates and standardized incidence ratios of HAV in Korean patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) from a nationwide population-based study (2013–2021)

(A) Incidence rate of HAV per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) in patients with IBD. (B) Incidence rate of HCV per 1,000 person-years (95% CI) in patients with IBD. HAV, hepatitis A virus; CI, confidence interval; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease.

Incidence of HCV in patients with IBD

A total of 289 cases of HCV infection were identified during 276,538 person-years (IR, 1.05/1,000 person-years; 95% CI, 0.93–1.17), while 242 cases of HCV infection developed in the Korean general population. The SIR of HCV in patients with IBD was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.06–1.34) (Table 3). In patients with UC, 212 HCV cases were identified over 176,597 person-years (IR, 1.20/1,000 person-years; 95% CI, 1.04–1.37), while 195 cases of HCV developed in the Korean general population. The SIR of HCV in patients with UC was 1.09 (95% CI, 0.85–1.14). In patients with CD, 77 cases of HCV were identified over 99,941 person-years (IR, 0.77/1,000 person-years; 95% CI, 0.61–0.96), while 47 cases of HCV developed in the Korean general population. The SIR of HCV in patients with CD was 1.63 (95% CI, 1.31–2.04) (Table 3, Fig. 2B, 3B). A tendency for the HCV IR to increase was confirmed in patients with CD, and an increase in the HCV IR was confirmed in patients with IBD under 39 years of age compared with the general population.

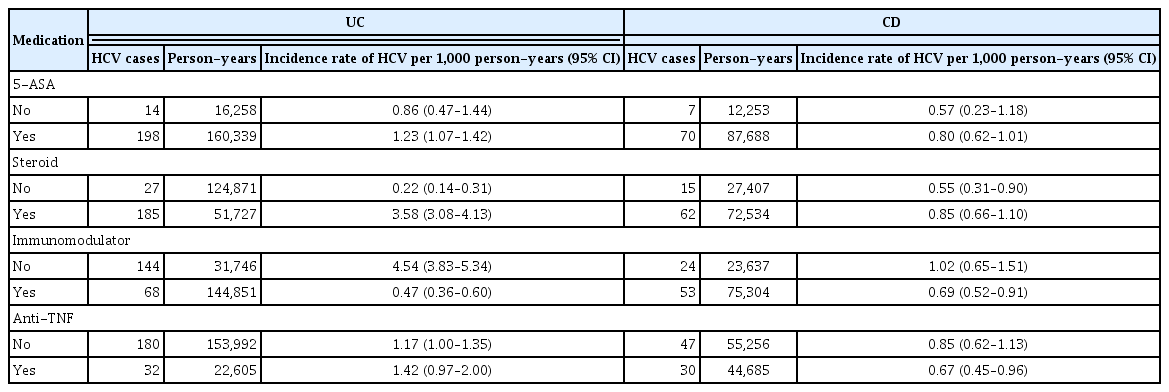

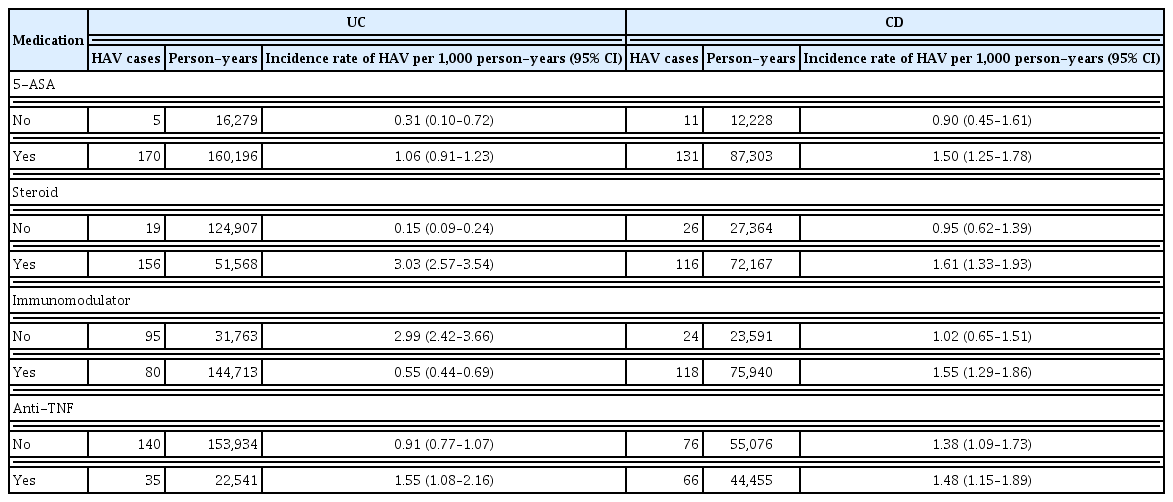

Incidence of HAV and HCV according to medication

The incidence of HAV was confirmed to increase in patients with IBD treated with 5-ASA, systemic steroids, and anti-TNF. In patients with UC, the incidence of HAV increased with the use of systemic steroids and anti-TNF. In patients with CD, immunomodulators, 5-ASA, and systemic steroids were all associated with an increased incidence of HAV (Table 4).

Incidence rates of HAV according to agents in Korean patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) from a nationwide population-based study (2013–2021)

Only systemic steroids were associated with an increased incidence of HCV in patients with IBD. In patients with UC, an association between systemic steroids and HCV infection risk was confirmed. However, there was no significant relationship between drug use and HCV infection in patients with CD (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that the risk of HAV infection is not higher in Korean patients with IBD than in the Korean general population, and that the risk of HCV infection is slightly higher in patients with CD. It has been shown that corticosteroid use is associated with the development of HAV and HCV.

There was a tendency for the HAV IR to increase in patients with IBD under 29 years of age and over 60 years of age, but there was no difference in the HAV IR between IBD and the general population among those aged 30–59 years in our study. The incidence of HAV did not increase in patients with UC, but an increasing trend was observed in patients with CD. No studies have investigated the association between HAV infection and IBD. HAV can be transmitted via the fecal-oral route (contaminated water or food) and prevented through vaccination. It occurs sporadically or epidemically around the world, and the IR varies depending on the social and economic level [6,15]. High-risk groups for HAV include those traveling to or working in countries with high or intermediate endemicity of HAV, men who engage in sexual activity with men, users of all illicit drugs, those working with HAV-infected primates or with HAV in a research laboratory, those with chronic liver disease, those with clotting factor disorders, and those in direct contact with others who have HAV [16]. Patients with IBD are not a high-risk group for HAV infection; however, if HAV infection occurs in immunocompromised patients, it can progress to acute liver failure and cause serious complications [7]. HAV infection is an important opportunistic infection in patients with IBD that can affect prognosis. Serological screening is recommended for patients with IBD, considering that many patients have weakened immunity owing to the use of immunomodulators or biological agents. Therefore, in patients with IBD who have not been vaccinated against HAV, whose vaccination history is uncertain, or who have no history of HAV infection, testing for HAV infection by measuring serum IgG anti-HAV antibody levels is recommended. If the results are negative, preventive measures are recommended. It would be beneficial to vaccinate all patients with IBD [17]. In patients aged 30–49, the prevalence of hepatitis A was confirmed to be lower in patients with UC and CD than in the general population. In most cases, antibody screening is performed before starting treatment for patients with UC and CD, and vaccination is recommended for those with preventable diseases if antibodies are absent. Therefore, the prevalence of hepatitis A is thought to be lower than in the general population.

Because HCV can be transmitted through blood, syringes, or sexual intercourse [10], it is known that the incidence of HCV may increase in patients with IBD who often undergo measures such as surgery or blood transfusion. In this study, the HCV IR increased in patients with CD, especially in patients under 39 years of age. The results of previous studies are diverse. A study conducted in France confirmed that HCV prevalence increased in patients with CD with a history of surgery compared to patients with UC. The seropositive prevalence of HCV was 5.98%, and blood transfusion was identified as a risk factor for HCV infection [18]. Additionally, in two studies from Italy, anti-HCV positivity was more common in patients with CD than in controls among patients younger than 50 years. This age-related trend was not observed in patients with UC [19]. However, three recent studies reported no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of HCV infection among patients with IBD compared to the general population [20–22]. A meta-analysis published in 2023 also showed that the HCV IR did not show a significant difference in patients with IBD but showed different results depending on the publication year [23]. If HCV is confirmed in a patient with IBD, treatment should be considered in the same way as in the general population. Additionally, because many immunosuppressive drugs used to treat IBD can impair liver function, it is recommended that patients with IBD should be screened for HCV infection at the time of diagnosis. However, in patients using biologics or small molecules, there may be interactions between HCV treatment drugs and IBD treatment drugs; therefore, care must be taken during treatment [17]. Therefore, when diagnosing IBD, screening tests are performed through anti-HCV measurement, and if positive, HCV RNA testing in the blood must be performed to confirm HCV infection [24–26].

Viral hepatitis is a very important problem in patients with IBD who use drugs associated with decreased immunity, because it can be fatal. Prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in patients with IBD, especially viral hepatitis, are important not only for national policies on medical consumption, but also for patient disease management [27,28]. In this study, the incidence of HAV in the IBD patient group was not significantly different from that in the general population, and the incidence of HCV was somewhat higher in patients with CD. This result is not significantly different from that of previous studies, and in this study, corticosteroid use was confirmed to slightly increase the incidence of HAV and HCV. Systemic corticosteroids are often used to treat UC or CD exacerbation. Therefore, to lower the risk of hepatitis, proper control of IBD is important. In addition, although the incidence of hepatitis in patients with IBD does not increase significantly, the use of immunosuppressive drugs is often necessary; therefore, it is necessary to perform HAV vaccination in advance, check HCV antibodies, and treat early if necessary.

This study reports the IR of HAV and HCV infections in patients with IBD compared to the general population and followed up all Koreans over 9 years using insurance claim data. However, this study had several limitations. First, because the recorded data were used for insurance claims, the patients’ medical history could not be verified. There was a possibility of misclassification in the context of the claims data [29]. To further increase the diagnostic accuracy of IBD, IBD medication prescriptions and RID codes were considered in addition to the IBD diagnosis codes. However, as not all patients with hepatitis visit the hospital and have a diagnosis code entered, some diagnoses may have been missed. For HAV, there is no specific treatment drug, and for HCV, treatment drugs are expensive; therefore, treatment cannot be administered to all diagnosed patients. Because hepatitis was defined only by a diagnosis code without additional drug claims, misclassification of the diagnosis may have occurred. This limitation may have led to an underestimation of the incidence of hepatitis in the general population. HAV and HCV infectious are diseases managed as national infectious diseases in Korea, requiring national reporting of infectious disease outbreaks upon diagnosis. Therefore, it is unlikely that the use of ICD codes would significantly impact diagnosis rates compared to other diseases. Nevertheless, the difficulty in identifying patients’ clinical course and antibody status is a limitation of this study, which utilized national data. Second, the IR and SIR of HAV and HCV in Korean patients with IBD according to drug exposure during the study period were calculated using nationwide claims data; however, this has the disadvantage of lacking disease-related information (IBD duration, disease phenotype, and disease severity). Third, despite efforts to address the issue of confounding effects of disease severity, further research is needed to incorporate additional factors, including comorbidities, that may influence hepatitis risk. Additionally, it was difficult to confirm the occurrence of complications related to hepatitis, such as liver failure, because medical records were not available. Additional research on this topic is needed in the future.

In conclusion, the risk of developing HCV infection is increased in Korean patients with IBD, especially in patients with CD and young patients. Immunosuppression by corticosteroids is an important risk factor for the development of hepatitis in patients with IBD. Therefore, it is important to control intestinal inflammation in patients with IBD in order to minimize corticosteroid use. Patients with IBD should be screened for HAV and HCV infections at the time of diagnosis, and in the case of HAV, vaccination may be necessary if there is no antibody.

KEY MESSAGE

1. The prevalence of hepatitis C tended to increase in younger patients with CD.

2. In particular, a tendency toward an increase in the prevalence of hepatitis C was observed as the use of corticosteroids increased.

3. Long-term, high-dose steroid use should be avoided in patients with IBD because it may increase the prevalence of viral hepatitis.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Jin Hwa Park: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing - original draft; Sang Hyoung Park: conceptualization, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision, project administration; Sang Pyo Lee: resources, supervision; Kang Nyeong Lee: resources, supervision; Hang Lak Lee: resources, supervision; Oh Young Lee: resources, supervision; Soorack Ryu: data curation, formal analysis, validation, software; Junwon Go: data curation, formal analysis, validation, software

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

None