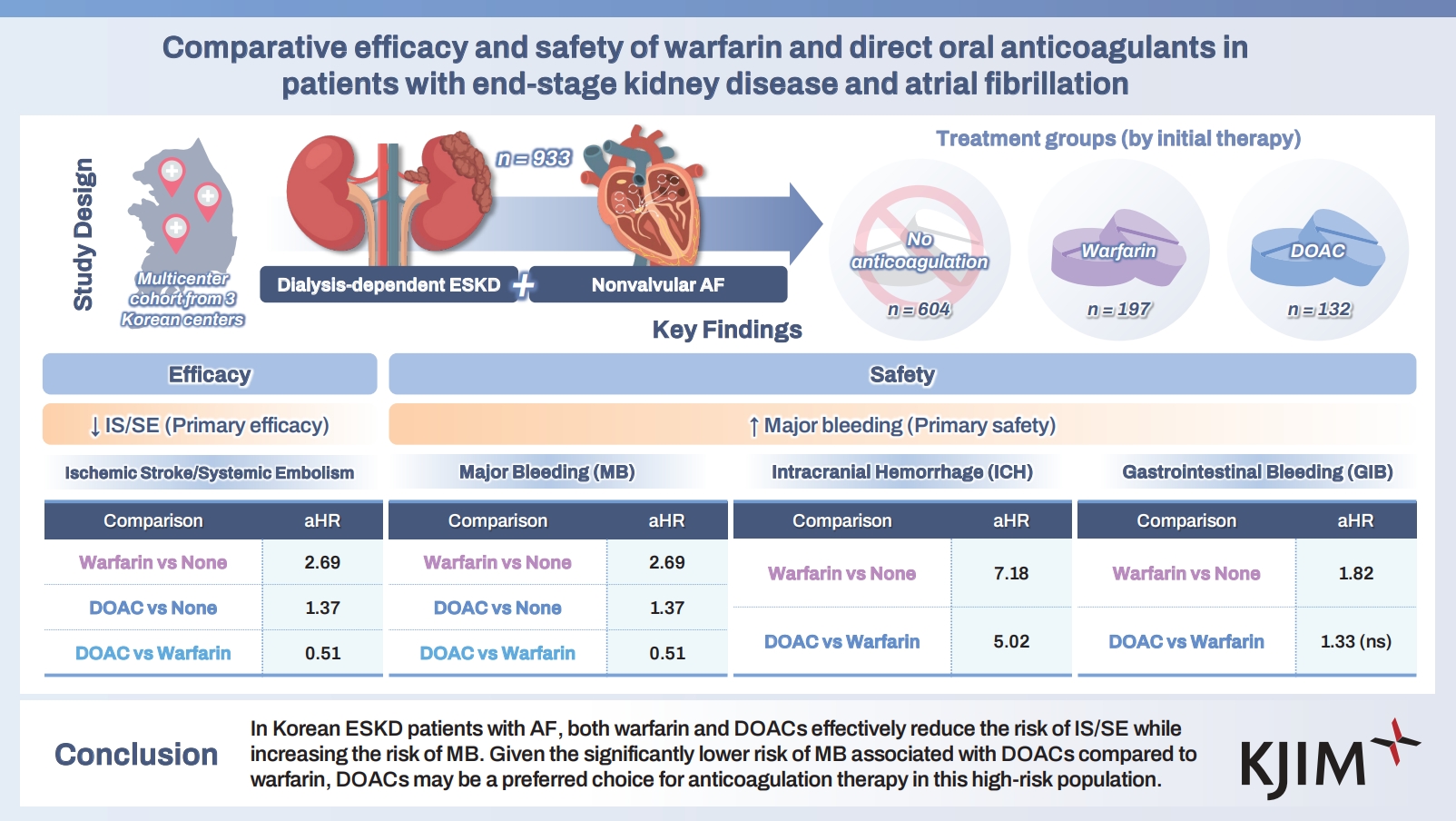

Comparative efficacy and safety of warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants in patients with end-stage kidney disease and atrial fibrillation

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) require careful anticoagulation because thrombotic and bleeding risks are both elevated. We evaluated the efficacy and safety of warfarin, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), and no anticoagulation in Korean patients with ESKD and AF.

Methods

In this multicenter retrospective study, we included 933 patients with ESKD and nonvalvular AF treated between 2010 and 2023. Patients were assigned to three groups by initial treatment: no anticoagulation (n = 604), warfarin (n = 197), or DOACs (n = 132). The primary efficacy outcome was ischemic stroke or systemic embolism (IS/SE); the primary safety out-come was major bleeding (MB). Secondary outcomes were intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB), and all-cause mortality. Inverse probability of treatment weighting was used to adjust for confounding.

Results

Both warfarin (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.55) and DOACs (aHR, 0.36) significantly reduced the risk of IS/SE compared with no anticoagulation. However, warfarin increased MB risk compared with no anticoagulation (aHR, 2.69), including ICH and GIB. DOACs also increased MB risk versus no anticoagulation (aHR, 1.37), driven primarily by ICH. Compared with warfarin, DOACs showed a lower MB risk (aHR, 0.51). Both warfarin and DOACs reduced all-cause mortality relative to no anticoagulation (aHR, 0.53 and 0.57, respectively).

Conclusions

Among Korean patients with ESKD and AF, both warfarin and DOACs reduced IS/SE but increased MB. Given their lower MB risk than warfarin, DOACs may be preferable for anticoagulation in this high-risk population.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of atrial fibrillation (AF) is rising and is projected to more than double by 2050–2060, posing a major public health burden in the United States and Europe [1,2]. Additionally, a progressive increase in AF prevalence has been observed in Korea (from 0.4% in 2006 to 1.53% in 2015) [3].

Because stroke and systemic embolism (SE) are strongly associated with AF, anticoagulation therapy is the cornerstone of preventing these events in patients at high embolic risk [4,5]. Before the introduction of the direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC), warfarin was the only option for anticoagulation in nonvalvular AF. Following four landmark randomized trials [6–9], DOACs became the preferred agents, offering similar efficacy and a superior safety profile compared with warfarin.

Despite these advances, the landmark trials excluded patients with severe renal insufficiency (defined as a creatinine clearance < 20 mL/min in the apixaban study [8] and < 30 mL/min in the other studies) [6,7,9]. Consequently, the use of DOACs in patients with severe renal insufficiency and AF—particularly those undergoing dialysis—remains controversial.

Many retrospective studies of patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) and AF have shown that warfarin does not consistently reduce the risk of ischemic stroke (IS) and is associated with similar or higher bleeding risk compared with no anticoagulation [10–12]. However, data from the Danish National Registry suggest that warfarin may reduce IS risk in this population [13].

With the increasing use of DOACs, several studies have compared their efficacy and safety with warfarin in patients with ESKD and AF. Findings have been conflicting: some studies indicate a benefit in stroke prevention [14], whereas others report comparable effectiveness and safety to warfarin [15]. Recent randomized trials comparing apixaban and warfarin in these patients were underpowered because of small sample sizes, leaving the question unresolved [16,17]. Given these uncertainties, anticoagulation for AF with severe renal impairment should be individualized. To address this gap, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of oral anticoagulants, including warfarin and DOACs, in this population.

METHODS

Data sources

Data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Study design and population

This multicenter retrospective study was conducted at Chungnam National University Hospital (CNUH), Chungnam National University Sejong Hospital (CNUSH), and Jeonbuk National University Hospital (JNUH). We included patients with ESKD and nonvalvular AF treated between January 2010 and December 2023. ESKD was defined as chronic kidney disease on dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis). Exclusion criteria were: (1) moderate to severe mitral stenosis; (2) mechanical prosthetic valve; (3) other conditions requiring anticoagulation, such as pulmonary thromboembolism; (4) not receiving dialysis; and (5) prescription of oral anticoagulants for less than 1 month.

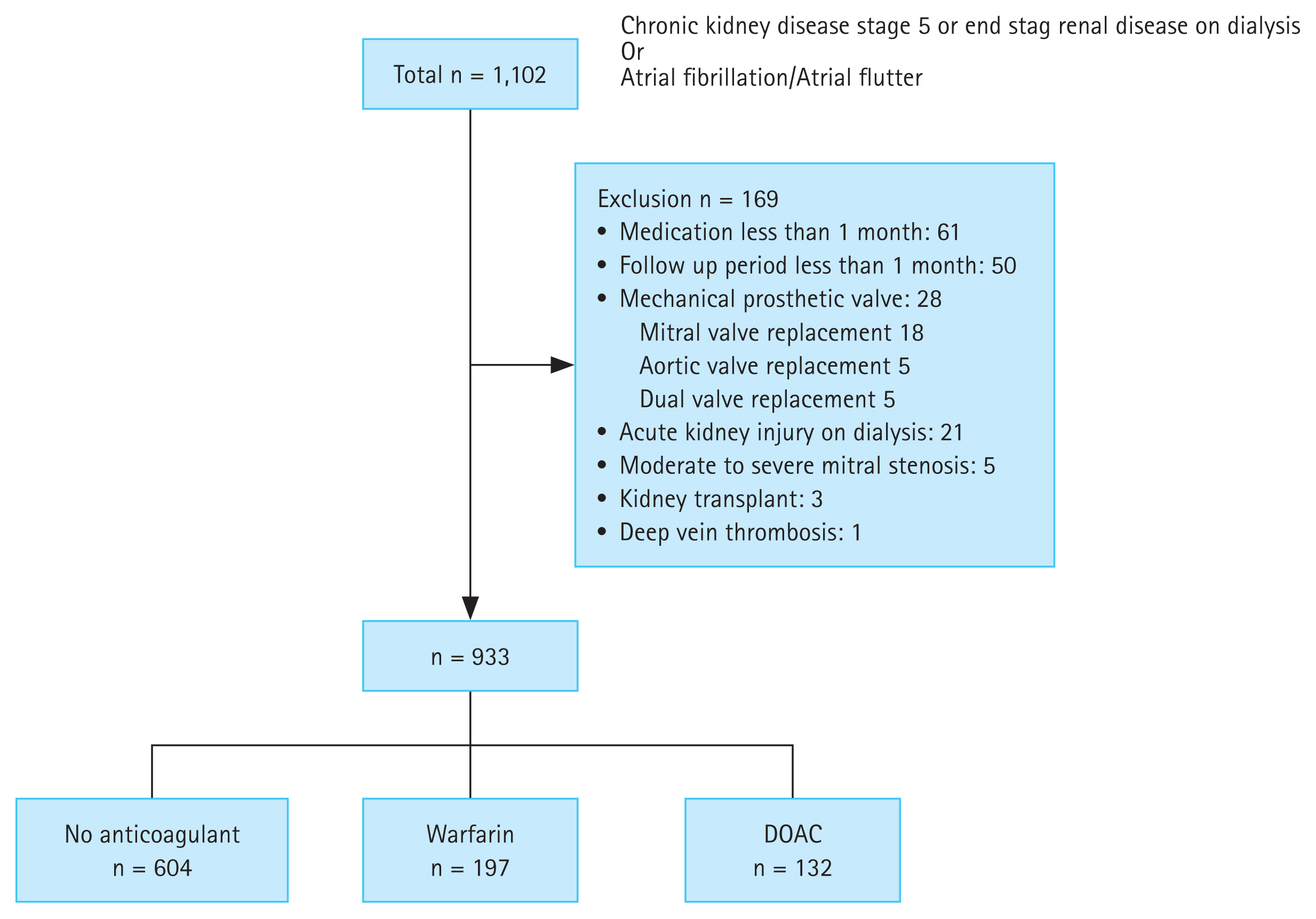

The study population flow chart is shown in Figure 1. The Institutional Review Board of Chungnam National University Hospital approved the study protocol (IRB no. CNUH/CNUSH, 2023-06-072; JNUH, 2024-04-019), and the requirement for informed consent was waived owing to the retrospective design. Patients and the public were not involved in the design, conduct, or dissemination of this study. All investigations were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical and laboratory data

Baseline clinical variables included age, sex, body mass index, and comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, liver disease, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, any history of stroke, coronary intervention, myocardial infarction, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, major bleeding (MB), valve surgery, and kidney transplantation. CHA2DS2-VASc (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 yr, diabetes, stroke/transient ischaemic attack, vascular disease, age 65–74 yr, and sex category) scores were also calculated [18]. Medication use during follow-up was recorded, including antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, renin–angiotensin system blockers, and statins.

Clinical outcomes and follow-up

Primary efficacy outcomes were IS and SE events (IS/SE). The primary safety outcome was MB, defined according to the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis criteria as fatal bleeding, symptomatic bleeding in a critical organ, or bleeding that reduced hemoglobin by ≥ 2 g/dL or required transfusion of ≥ 2 units of whole blood or red cells [19]. The secondary efficacy outcome was all-cause mortality; secondary safety outcomes were intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) and gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB). ICH was defined as any bleeding within the intracranial vault, including the brain parenchyma and meningeal spaces [20]. The index date was the first AF diagnosis for patients with ESKD not receiving anticoagulation and the first prescription date for warfarin or DOAC for treated patients.

Statistical analysis

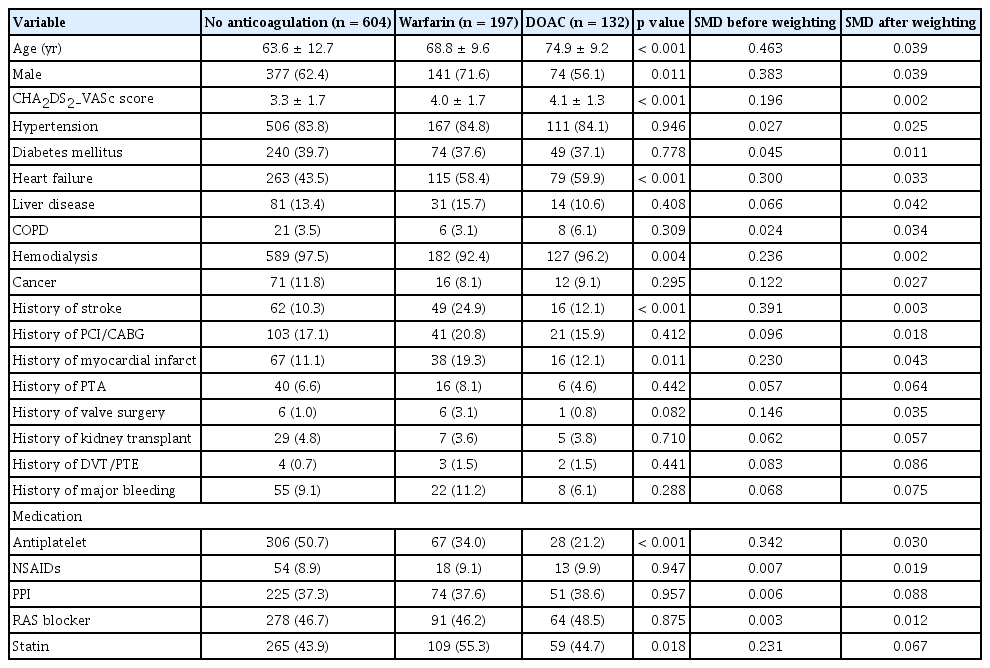

Baseline characteristics (demographics, comorbidities, risk factors, and medication use) were summarized by treatment group. Categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were summarized as means and standard deviations and compared using ANOVA (analysis of variance).

Incidence rates were calculated as events per 1,000 person-years. All analyses were truncated at 2 years of follow-up to account for differences in follow-up by treatment and the small numbers beyond 2 years in the warfarin and DOAC groups.

Cox proportional hazards regression was used for clinical outcome analyses. The proportional hazards assumption was evaluated by inspecting log(-log[survival]) plots and testing Schoenfeld residuals; no violations were detected. To reduce confounding, we used propensity scores to adjust imbalances across treatment groups. The propensity score for assignment to no anticoagulation, warfarin, or DOAC was estimated with a multinomial logistic regression that included age and CHA2DS2-VASc score (continuous) and the following categorical covariates: sex, heart failure, history of stroke, history of myocardial infarction, history of peripheral artery intervention, history of valve surgery, liver disease, cancer, type of dialysis, history of MB, antiplatelet medication, proton pump inhibitor medication, and statin medication. Variables with a standardized mean difference (SMD) > 0.1 among groups were included. Given the sample size (n = 933), the number of covariates was limited. Based on the propensity score, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was applied to balance covariates across the three groups (no anticoagulation, warfarin, and DOAC) [21]. The C-statistic (concordance statistic) for the propensity model was 0.69. Covariate balance between groups was assessed using SMDs, with SMD ≤ 0.1 considered adequate. Balance before and after weighting is shown in Table 1.

In subgroup analyses, univariable Cox proportional hazards models were used, and p for interaction was calculated.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R version 4.0.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). A p < 0.05 was considered significant.

DOAC dose

To compare efficacy and safety within the DOAC group, we categorized patients as regular dose or low dose. Regular dose was defined as full-dose DOAC therapy (apixaban 5 mg twice daily, rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily, edoxaban 60 mg once daily, or dabigatran 150 mg once daily); all other regimens were classified as low dose.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Among 933 patients with ESKD and nonvalvular AF, anticoagulation strategies were no anticoagulation (n = 604), warfarin (n = 197), and DOACs (n = 132). Among DOAC users, apixaban was prescribed in 55% (n = 73), rivaroxaban in 30% (n = 39), edoxaban in 14% (n = 18), and dabigatran in 2% (n = 2). Overall, 79% of DOAC users (n = 104) received low-dose regimens.

Before propensity score weighting, compared with patients not receiving anticoagulation, anticoagulant users were generally older, had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores, were more likely to have heart failure, and were less likely to receive antiplatelet therapy. Compared with DOAC users, warfarin users were predominantly male, had higher rates of prior stroke and myocardial infarction, were less likely to undergo hemodialysis, and were more likely to use statins (Table 1). After weighting, baseline variables were well balanced across the three treatment strategies (Table 1).

Outcomes and follow-up

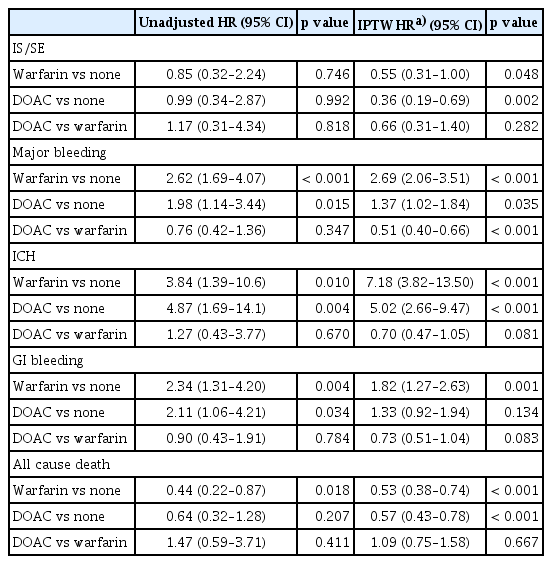

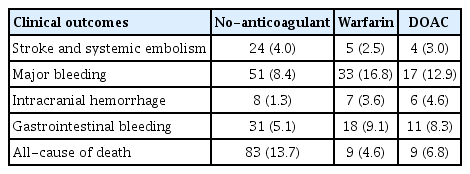

The median follow-up was 3.0 years (interquartile range, 0.8–8.6 yr). Adverse clinical outcomes at 2 years are shown in Table 2.

Event number and incidence rate at 2 years for no-anticoagulant, warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants group

Relative to no anticoagulation, both warfarin (IPTW-adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.31–1.00; p = 0.048) and DOACs (IPTW aHR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.19–0.69; p = 0.002) were associated with a lower risk of IS/SE.

For safety outcomes, warfarin was associated with a higher risk of MB (IPTW aHR, 2.69; 95% CI, 2.06–3.51; p < 0.001) driven by increased risks of both ICH (IPTW aHR, 7.18; 95% CI, 3.82–13.50; p < 0.001) and GIB (IPTW aHR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.27–2.63; p = 0.001) versus no anticoagulation. DOACs were also associated with a higher risk of MB (IPTW aHR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.02–1.84; p = 0.035) versus no anticoagulation. DOAC users had an increased risk of ICH (IPTW aHR, 5.02; 95% CI, 2.66–9.47; p < 0.001) but a similar risk of GIB (IPTW aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 0.92–1.94; p = 0.134) (Table 3).

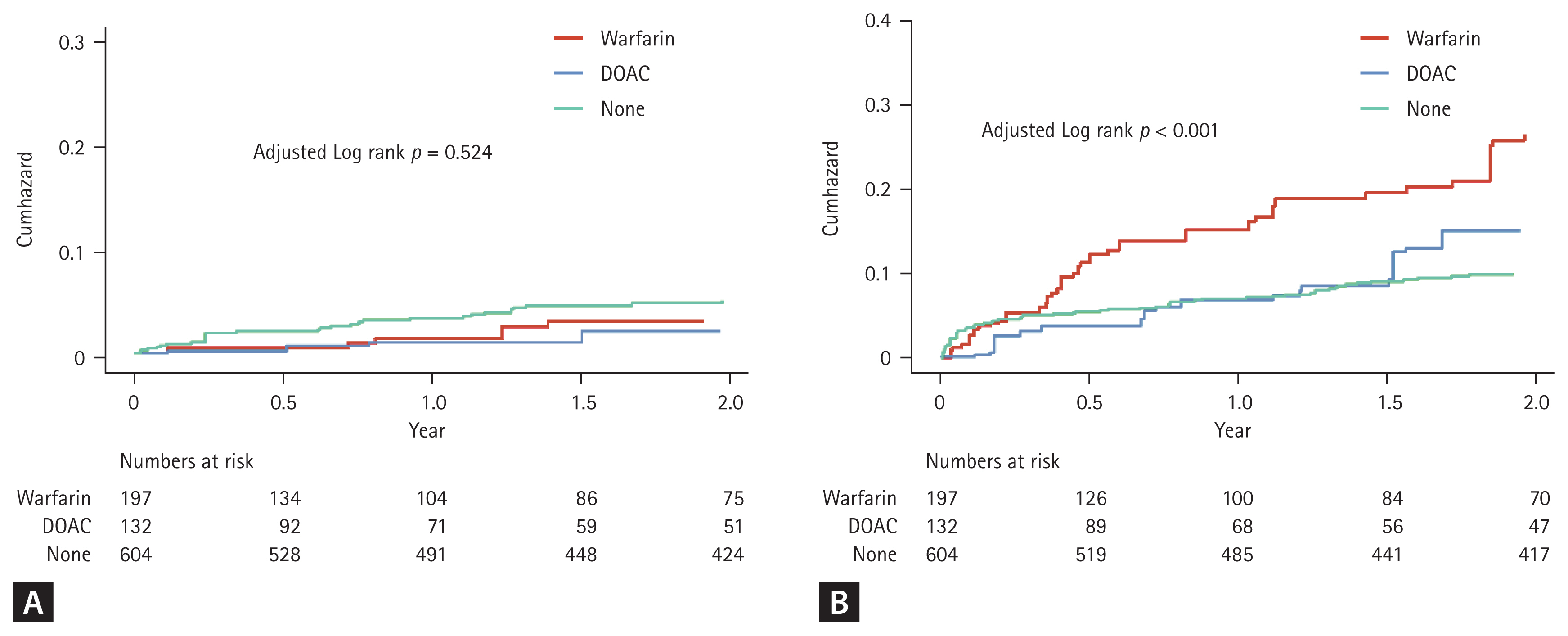

Both warfarin (IPTW aHR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.38–0.74; p < 0.001) and DOACs (aHR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.43–0.78; p < 0.001) were associated with lower all-cause mortality compared with no anticoagulation (Table 3, Fig. 2, and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Weighted cumulative incidence curves of the primary outcomes for the warfarin, DOAC and no anticoagulation groups for patients with atrial fibrillation and end stage renal disease. (A) Stroke and systemic embolism. (B) Major bleeding. DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant.

DOACs had a risk of IS/SE comparable with warfarin (IPTW aHR, 0.66 [0.31–1.40]; p = 0.282) and were associated with a significantly lower risk of MB (IPTW aHR, 0.51 [0.40–0.66]; p < 0.001). DOACs also showed trends toward lower risks of ICH (IPTW aHR, 0.70 [0.47–1.05]; p = 0.081) and GIB (IPTW aHR, 0.73 [0.51–1.04]; p = 0.083); however, these differences were not statistically significant. All-cause mortality was similar between DOACs and warfarin (IPTW aHR, 1.09 [0.75–1.58]; p = 0.667).

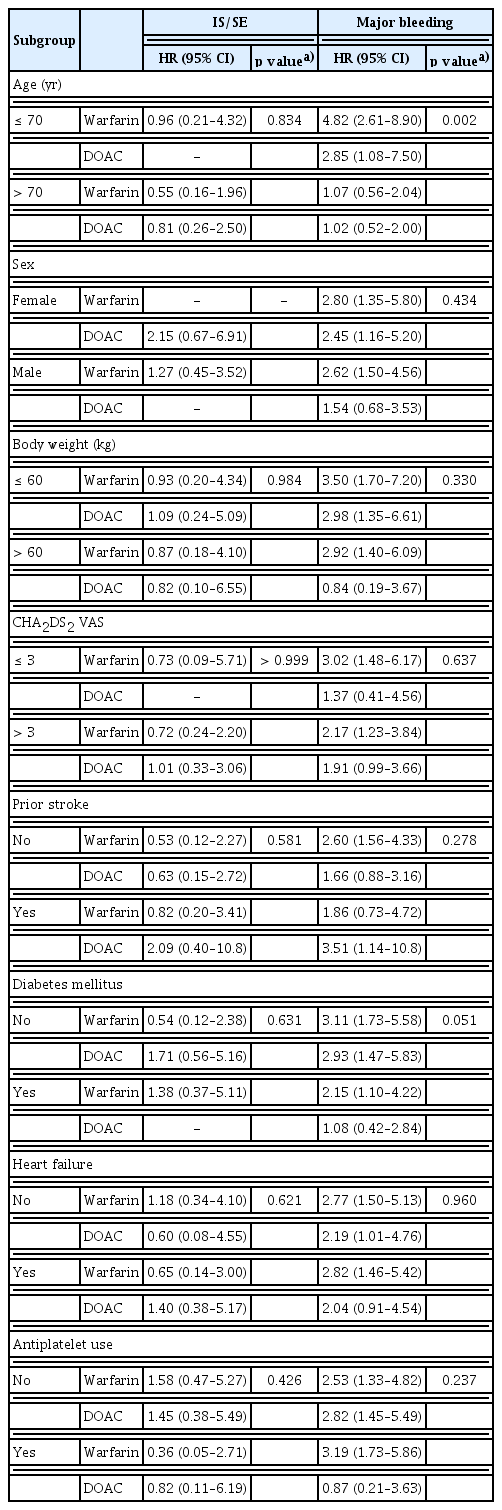

Subgroup analysis

Crude event counts for clinical outcomes by treatment across subgroups are presented in Supplementary Table 1. HRs for the primary outcomes are shown in Table 4. Age significantly interacted with treatment for MB. Among patients aged > 70 years, both warfarin (aHR, 1.07 [0.56–2.04]; p for interaction = 0.002) and DOACs (aHR, 1.02 [0.52–2.00]; p for interaction = 0.002) showed a trend toward lower MB risk relative to the corresponding treatments in patients aged < 70 years.

Of the 132 DOAC users, 73 (55%) received apixaban and 39 (30%) received rivaroxaban. Crude event counts and HRs for clinical outcomes for apixaban and rivaroxaban are shown in Supplementary Table 2. Clinical outcomes did not differ significantly between apixaban and rivaroxaban. Among DOAC users, 104 (79%) received low-dose DOACs and 28 (21%) received regular-dose DOACs. Crude event counts and HRs by DOAC dose are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Low-dose DOACs tended to be associated with lower ICH risk, with no significant differences in other outcomes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared the efficacy and safety of warfarin, DOACs, and no anticoagulation in patients with ESKD and nonvalvular AF. Key findings were as follows: (1) both warfarin and DOACs reduced IS/SE risk compared with no anticoagulation; (2) warfarin was associated with a higher risk of MB, including ICH and GIB, compared with no anticoagulation; (3) DOACs also increased MB risk—primarily due to ICH—while presenting a risk of GIB comparable with no anticoagulation; (4) relative to warfarin, DOACs provided similar efficacy for IS/SE but better safety, with lower tendencies for ICH and GIB; (5) both warfarin and DOACs were associated with reduced all-cause mortality compared with no anticoagulation; and (6) subgroup analyses suggested better safety for both warfarin and DOACs in patients aged > 70 years.

The prevalence of ESKD in Korea is 157 per 100,000 and continues to rise, particularly among older adults. Mortality is especially high in individuals aged > 75 years, among whom cardiovascular death accounts for 20% [22]. AF is common in patients with ESKD, with a prevalence of 6% to 20% [23]. Shared risk factors—including diabetes, heart failure, advanced age, and vascular disease—likely contribute to this burden. In our cohort, risk factors were frequent: 85% had hypertension, 40% had diabetes, and 19% had a history of coronary revascularization. Compared with an age- and sex-matched population, AF is more prevalent in patients with ESKD [24], and AF independently increases mortality in this population [23]. Because a substantial proportion of cardiovascular deaths is due to cerebral infarction, anticoagulation is essential to reduce mortality. Nevertheless, optimal strategies remain uncertain given the scarcity of randomized controlled trials and conflicting retrospective evidence. Despite high CHA2DS2-VASc scores, only 35% of patients in this study received anticoagulation, reflecting concerns about bleeding risk.

ESKD is associated with alterations of the coagulation system, including endothelial and platelet dysfunction, and patients with ESKD have increased risks of both thrombosis and hemorrhage [25]. Renal dysfunction is an independent risk factor for stroke; an inverse linear relationship has been observed between glomerular filtration rate and stroke risk, which increases by 7% for each 10 mL/min/1.74 m2 decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate [26]. Accordingly, the concurrent risks of thrombosis and bleeding complicate anticoagulation decision-making. Warfarin was the only available anticoagulant for many years. However, its use is problematic—not only because of increased bleeding risk but also because it is a risk factor for calciphylaxis, a rare yet fatal disease [27]. Prior studies have reported conflicting effects on stroke prevention, but a consistent increase in bleeding risk [10–13,15,28]. These findings complicate decisions about warfarin use in patients with ESKD and AF. In the present study, warfarin was associated with a lower risk of IS/SE, consistent with the Danish National Registry study [13]. Warfarin nearly tripled the risk of MB (aHR, 2.69), which appears somewhat higher than in previous reports (aHR, 1.2–2.0) [10,12,13,28,29]. One possible explanation for the higher MB risk in our cohort is concomitant antiplatelet therapy: approximately 34% of warfarin-treated participants also received antiplatelet agents, which may have increased bleeding risk relative to other studies.

As DOACs have become the anticoagulant of choice for nonvalvular AF, the efficacy and safety of DOACs in severe renal insufficiency, including ESKD, are being actively investigated. In several meta-analyses of patients with severe renal insufficiency not receiving dialysis, DOACs showed superior efficacy and safety compared with warfarin [14,30]. In a meta-analysis including studies of patients with ESKD, DOACs were noninferior to warfarin for both efficacy and safety [29]. In a retrospective U.S. study of patients with ESKD, apixaban was not associated with a lower risk of IS/SE compared with no anticoagulation, but its use was associated with increased risks of death or ICH [31]. Collectively, these findings suggest that DOACs may be a safer alternative to warfarin in ESKD, although the risk of fatal bleeding events such as ICH may be increased.

Three randomized trials compared DOACs with warfarin in patients with ESKD and AF [16,17,32]. Each was underpowered, precluding definitive conclusions; nevertheless, clinically relevant bleeding was frequent (approximately 20– 30%). In a meta-analysis of these trials [33], DOACs were non-inferior to warfarin for both efficacy and safety [33]. Collectively, these findings suggest that DOACs may be a safer option than warfarin in ESKD. Notably, none of the trials included a no-anticoagulation group, which prevented direct comparisons with no therapy. In our study, DOACs reduced IS/SE relative to no anticoagulation and showed an intermediate bleeding risk—lower than warfarin but higher than no anticoagulation. Therefore, when anticoagulation is indicated, DOACs may be preferable to warfarin in this population.

All four DOACs undergo renal elimination, with dabigatran showing the highest renal excretion (80%), followed by edoxaban (50%), rivaroxaban (35%), and apixaban (27%) [34]. In patients on hemodialysis, apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily and rivaroxaban 10 mg once daily produced drug concentrations comparable to standard dosing in patients with preserved renal function [35,36]. In our cohort, 79% received low-dose regimens. Low-dose DOACs tended to lower ICH risk without increasing IS/SE. Although several studies in Asian populations report favorable safety with low-dose DOACs [37,38], Korean national data indicate that off-label apixaban underdosing confers no efficacy benefit [39]. Current dosing criteria do not differ by ethnicity, and evidence to guide dosing in dialysis remains limited. Larger studies are needed to define optimal dosing in this setting. In our study, most DOAC users received apixaban (55%) or rivaroxaban (30%). Although underpowered for head-to-head comparisons, we observed no significant differences between these two agents.

In subgroup analyses, patients aged > 70 years in the DOAC group tended to have a lower MB risk, supporting use in older adults. No significant interactions were detected in other subgroups.

This study hadlimitations. First, its retrospective design introduced potential confounding that could affect both outcomes and treatment selection. Because anticoagulation in ESKD remains controversial, clinicians chose therapy based on individual clinical status; thus, these findings should be viewed as hypothesis-generating. Second, we did not calculate time in therapeutic range for the warfarin group due to the large number of international normalized ratio measurements. Third, the DOAC group included all four agents—most commonly apixaban (55%) and rivaroxaban (30%)—limiting type-specific inferences. Fourth, subgroup analyses were exploratory and not powered for definitive conclusions. Strengths include the multicenter design, detailed chart review, and three-group comparison. Overall, DOACs lowered IS/SE risk and were safer than warfarin but were associated with more thromboembolic events than no anticoagulation.

In patients with ESKD and AF, both warfarin and DOACs reduced IS/SE compared with no anticoagulation but increased MB, including ICH. DOACs showed better safety than warfarin, with lower tendencies for ICH and GIB. Both therapies were associated with lower mortality. When anticoagulation is considered, DOACs may represent a safer alternative to warfarin. Prospective studies are needed to determine the optimal DOAC agent and dosing in this population.

KEY MESSAGE

1. In patients with AF and ESKD, both warfarin and DOACs reduce IS and SE compared with no anticoagulation.

2. DOACs increase MB compared with no anticoagulation but have lower MB risk than warfarin.

3. Clinicians may consider DOACs as a viable alternative to warfarin for patients with ESKD at high ischemic risk.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Yujin Yang: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing; Sun Hwa Lee: data curation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing; WonMook Hwang: investigation, data curation, writing - original draft; Ji Hoon Jung: formal analysis, software; Jae-Hyeong Park: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

This research was supported by the research fund from the Chungnam National University Hospital (2022).