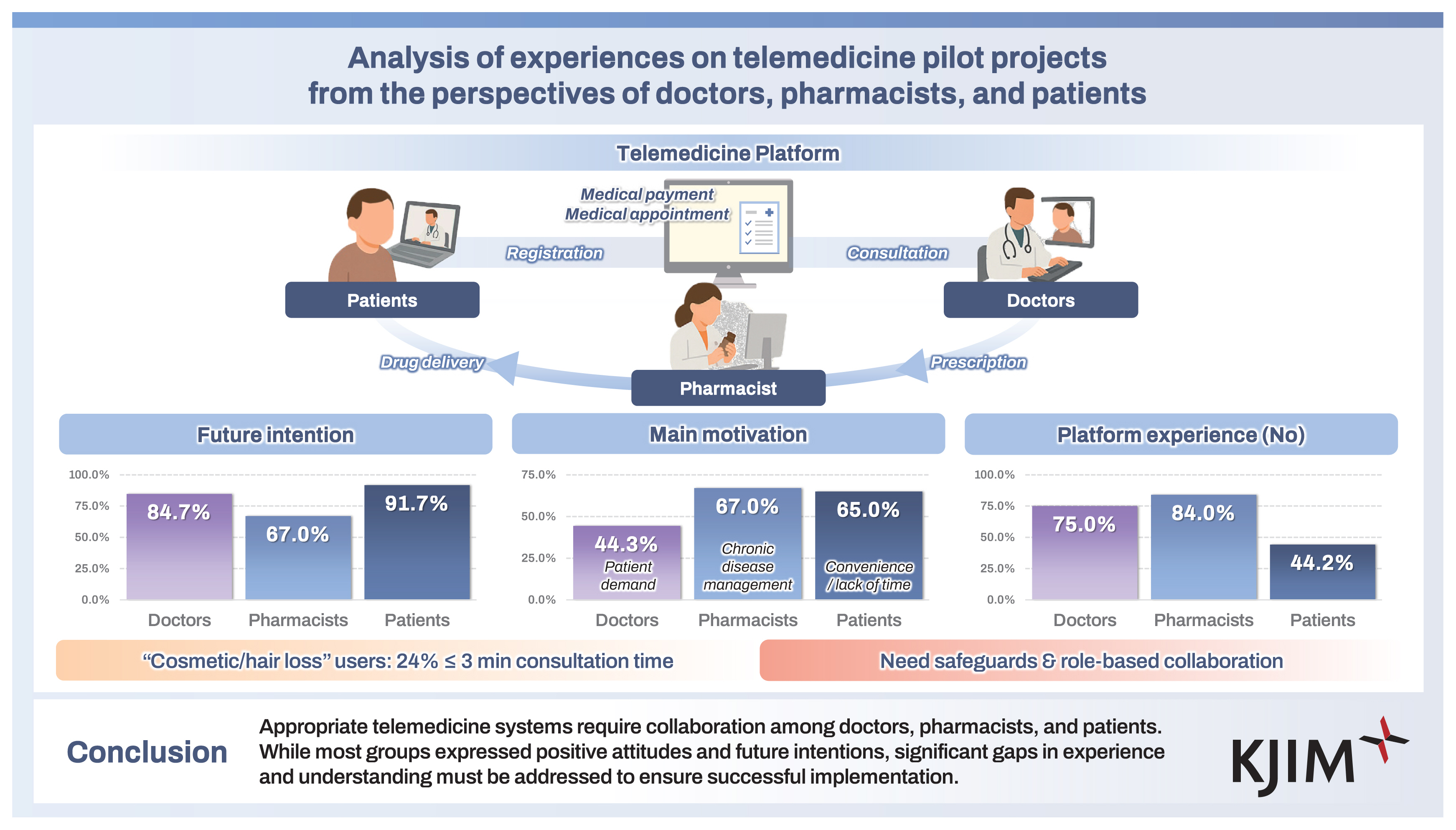

Analysis of experiences on telemedicine pilot projects from the perspectives of doctors, pharmacists, and patients

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

This study is the first to analyze telemedicine pilot project experiences from doctors, pharmacists, and patients with different roles to support sustainable commercialization.

Methods

An online survey targeted individuals (patients, doctors, and pharmacists) who participated in the telemedicine pilot project at least once between June 1, 2023, and July 17, 2024. The survey assessed satisfaction and usage conditions. The online survey conducted between May 2024 and July 2024 included 1,500 patients, 300 doctors, and 100 pharmacists.

Results

Doctors, pharmacists, and patients all expressed their intention to participate actively in telemedicine in the future; however, pharmacists showed lower participation rates than doctors (84.7% vs. 67.0% vs. 91.7%, p < 0.001). The most common reason among doctors was “increasing demands from patients” (44.3%), while for pharmacists, it was “easy management of patients with chronic diseases” (67.0%). This showed a statistically significant difference between groups (p < 0.001). Among patients, 65.0% cited “lack of time and convenience.” Notably, both doctors and patients agreed that telemedicine requires more time than current practices, although their perceptions differed significantly (all p < 0.001). Additionally, 24.0% of patients who used telemedicine for “hair loss/beauty” purposes reported treatment times of “≤ 3 minutes” shorter than for other purposes. Regarding telemedicine platforms, 75.0% of doctors and 84.0% of pharmacists reported no prior experience using them.

Conclusions

Appropriate telemedicine systems require collaboration among doctors, pharmacists, and patients. While most groups expressed positive attitudes and future intentions, significant gaps in experience and understanding must be addressed to ensure successful implementation.

INTRODUCTION

Telemedicine is a medical service enabling doctors to monitor health, examine, and prescribe to patients outside medical institutions using information and communication technology [1]. In 2020, when the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic crisis level was raised to ‘serious,’ telephone consultations and prescriptions were temporarily permitted [2]. However, as the epidemic level decreased, this temporary telemedicine ended in June 2023, but as the infectious disease epidemic level was lowered, temporary telemedicine ended in June 2023 [3]. Under Article 44 of the Framework Act on Health and Medical Services, a telemedicine pilot project was launched, focusing on clinic-level medical institutions and returning patients [4]. On December 15, 2023, the pilot project was reorganized to include simplified criteria for those with prior face-to-face treatment, expanded coverage for medically vulnerable areas, availability of telemedicine on holidays and at night, and restrictions on prescribing emergency contraceptives [5]. Additionally, from February 23, 2024, telemedicine became available at all types of medical institutions, including hospitals, following measures allowing temporary telemedicine [6].

In other countries, telemedicine introduced during the COVID-19 pandemic has been sustained even after the pandemic transitioned [7,8]. In addition, the effectiveness of telemedicine for each major disease, such as diabetes management [9,10], neurological disease prognosis management [11–13], and improvement of symptoms of depression and anxiety in older adults [14,15] has been evaluated in various studies. These assessments inform system revisions and enhancements. Therefore, it is crucial to derive improvement strategies by evaluating Korea’s current telemedicine pilot project and reviewing evidence-based institutionalization measures.

While the telemedicine system is essential, it is equally important to consider the experiences of doctors, pharmacists, and patients. The perspectives of healthcare providers delivering telemedicine and patients utilizing it differ significantly. In particular, including patient feedback is crucial for assessing user experiences and identifying barriers and facilitators to the effective use of telemedicine services. Their insights are vital for ensuring that the system meets the needs of its users. As the telemedicine pilot project advances, this study seeks to identify areas for improvement by evaluating the perceptions of doctors, pharmacists, and patients involved in the initiative. The ultimate goal is to develop a plan for institutionalizing telemedicine. By surveying both users and providers, we aim to generate reliable data on the sustainability of the telemedicine system, highlighting its strengths and weaknesses.

METHODS

An experience survey was conducted using a structured questionnaire to understand the usage patterns of doctors and pharmacists participating in the telemedicine pilot project. The survey targeted individuals who had used telemedicine at least once between June 1, 2023, when the telemedicine pilot project began, and July 2024, when the survey concluded. The survey was administered online.

Study population

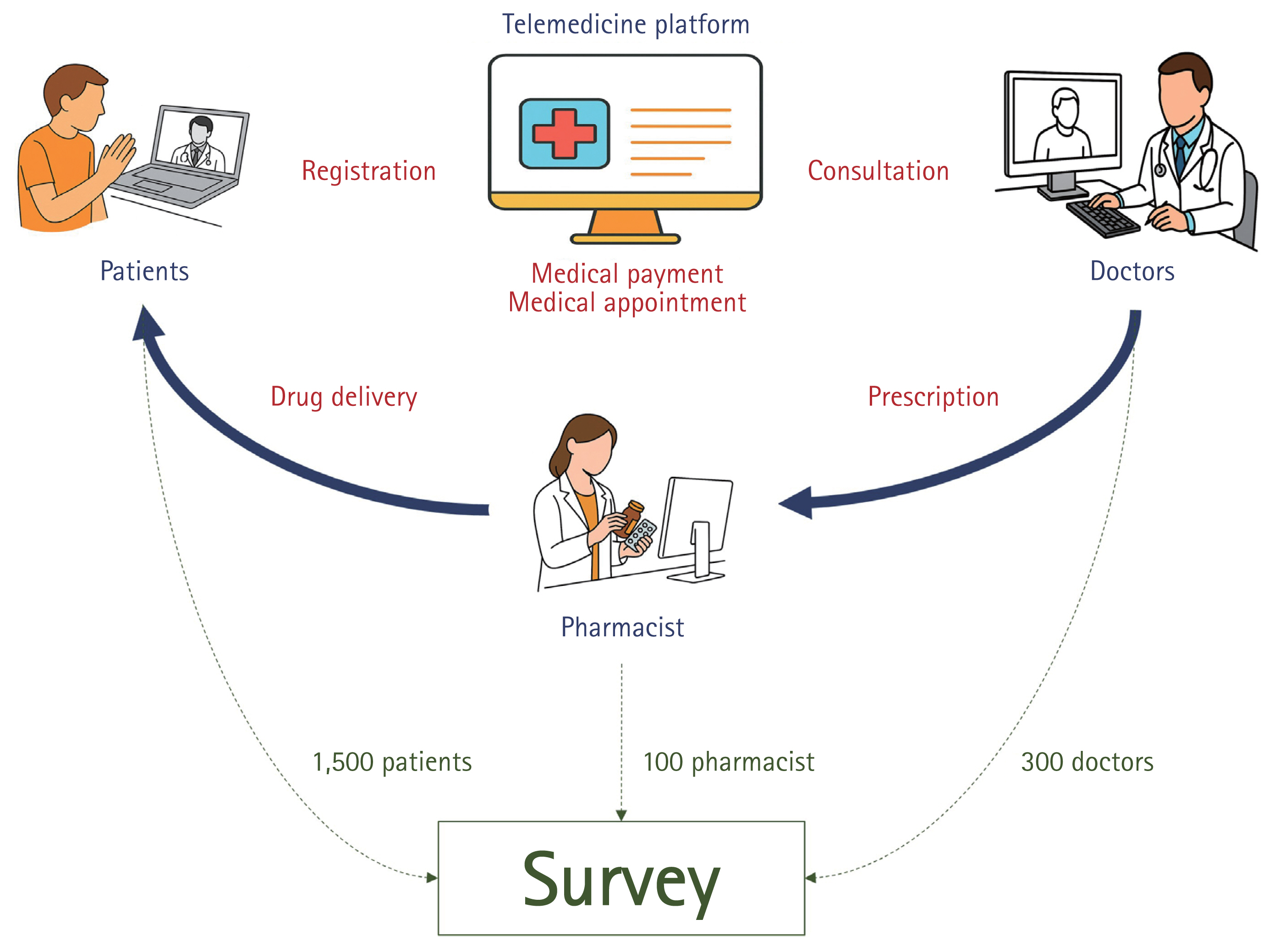

Survey participants were selected using panel data from a research company as the sampling frame. Additionally, doctors and pharmacists experienced in telemedicine were recruited from the list of medical institutions participating in the telemedicine pilot project published on the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service website [16]. The cumulative number of patients participating in the telemedicine pilot project was estimated to average approximately 84,600 per month. Assuming this trend continued, the total number of patients over one year was projected to reach around 1 million. Accordingly, the population was set at approximately 1 million, and with a 95% confidence level and a ± 2.5% margin of error, the required sample size was calculated to be 1,500. Inclusion criteria targeted patients who had utilized telemedicine at least once since the project’s implementation on June 1, 2023. Participants were recruited using sex, age, residential area, and number of telemedicine experiences as stratification variables, reflecting their distribution. The survey link was sent to those who voluntarily wished to participate, and the response rate was 57.6% for doctors, 39.5% for pharmacists, and 45.4% for patients. Participants included 1,500 patients, 300 doctors, and 100 pharmacists recruited via panel data from a research company and the list of telemedicine institutions published by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (Fig. 1). Consent was obtained from all participants through an online consent form. The Institutional Bioethics Committee of the Korea Institute of Health and Medical Research approved the survey prior to implementation (IRB No: NECA IRB23-020).

Study design

In Korea, telemedicine services are conducted in accordance with established guidelines [5]. Patients initiate the process by calling the medical institution to make a reservation and register for a consultation. They then wait for their turn on the platform and, when called, receive a consultation, primarily via video. Following the consultation, patients can pay their medical fees and receive prescriptions through the platform. To investigate the usage status and improvement needs of patients, doctors, and pharmacists regarding telemedicine, the survey was designed with reference to domestic and international studies. It included questions on the respondents’ basic characteristics, experience with telemedicine, satisfaction with telemedicine, effectiveness of the telemedicine pilot project, and opinions on the allowable scope and costs of telemedicine (Supplementary Fig. 1). Expert consultation determined the suitability of the tool selected based on the final literature. Survey questions were also designed by referencing prior surveys on telemedicine pilot projects and incorporating expert input. This survey was administered using a computer-assisted web survey (CAWI) system from June 19 to July 17, 2024. The CAWI system used programmed logic to ensure consistency in responses, verifying discrepancies in real time during data collection.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as frequency and percentage distributions for categorical data, while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Participant characteristics between groups were compared using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Analysis of variance and Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparison test were used to assess significant differences among group means and identify specific group differences. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (Version 26.0; IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA). p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The web survey link was sent via email or text message exclusively to participants who voluntarily opted in. For patients, panel information registered with the research company was used, and for doctors and pharmacists, the registered panel information or the contact details collected with consent during the application process were used. If there was no response, the link was resent up to five times to encourage participation. Data collection was completed over one month (June 19 2024–July 17, 2024), with responses from 300 doctors, 100 pharmacists, and 1,500 patients. A total of 1,900 participants were included in this study.

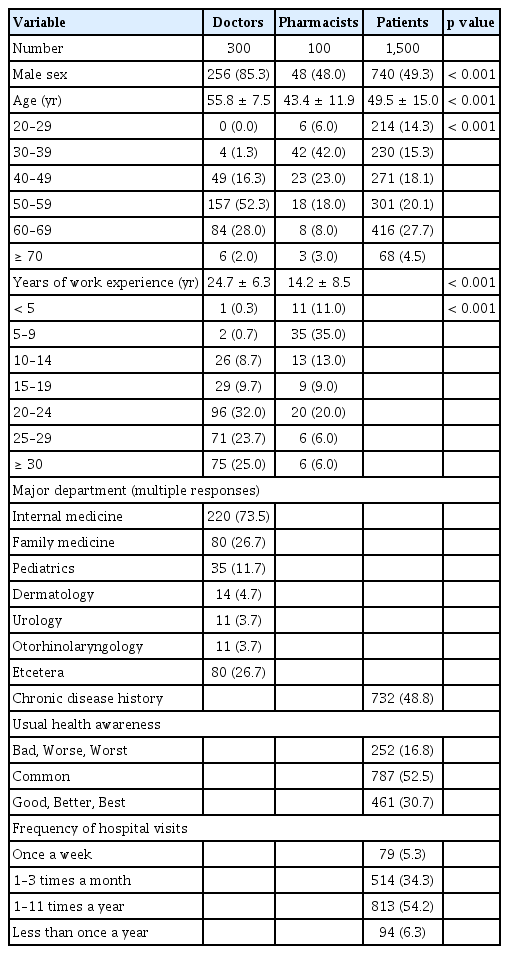

Baseline characteristics

A total of 300 doctors participated in the survey (Table 1). Among them, 256 were male (85.3%) and 44 were female (14.7%), with an average age of 55.8 ± 7.5 years. The largest age group was 50–59 years (52.3%, 157/300), followed by those aged 60–69 years (28.0%, 84/300) and 40–49 years (16.3%, 49/300). The average work experience was 24.7 ± 6.3 years, with the highest proportion (32.0%, 96/300) having 20–24 years of experience, followed by over 30 years (25.0%, 75/300) and 25–29 years (23.7%, 71/300). Most doctors worked at the clinic level (95.7%, 287/300), with 4.3% (13/300) working at the hospital level. The majority were private practitioners (92.0%, 276/300). The primary specialties were internal medicine (73.5%, 220/300), family medicine (26.7%, 80/300), and pediatrics (11.7%, 35/300). Among the 100 pharmacists, there were more females (52.0%, 52/100) than males (48.0%, 48/100). The average age was 43.4 ± 11.9 years. The largest age group was 30–39 years (42.0%, 42/100), followed by 40–49 years (23.0%, 23/100) and 50–59 years (18.0%, 18/100). The average work experience was 14.2 ± 8.5 years, with 35.0% (35/100) having 5–9 years of experience, 20.0% (20/100) having 20–24 years, and 13.0% (13/100) having 10–14 years. A total of 1,500 patients participated, with an average age of 49.5 ± 15.0 years. The largest age group was 60–69 years (27.7%, 416/1,500), followed by 50–59 years (20.1%, 301/1,500) and 40–49 years (18.1%, 271/1,500). Participants were selected from various age groups.

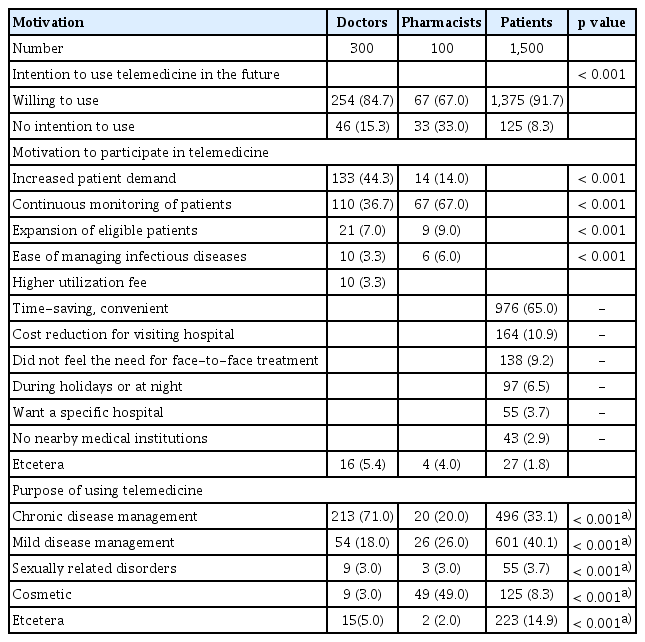

Motivation for participation and main purpose in telemedicine

Consequently, both doctors and pharmacists expressed willingness to participate in telemedicine in the future, though doctors (84.7%, 254/300) and patients (91.7%, 1,375/1,500) demonstrated statistically significantly higher willingness compared to pharmacists (67.0%, 67/100) (84.7% vs. 67.0%, p < 0.001) (Table 2). The primary motivation for doctors to participate in telemedicine was “increased patient demand” (44.3%, 133/300) and “continuous management of patients with chronic diseases” (36.7%, 110/300). In contrast, pharmacists were primarily motivated by “continuous management of patients with chronic diseases” (67.0%, 67/100), highlighting a significant difference in motivations between doctors and pharmacists (p < 0.001). Additionally, both doctors (7.0%, 21/300) and pharmacists (9.0%, 9/100) indicated a relatively high motivation to participate in telemedicine due to the potential for expanding their patient base. Patients, on the other hand, were primarily motivated by time savings and convenience, cited by 65.0% (976/1,500). Among patients using telemedicine at doctors’ offices, the most common purpose was managing chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (73.2%, 210/287). A smaller but notable proportion sought telemedicine for mild conditions like colds, fevers, allergies, or headaches (18.5%, 53/287). In contrast, at pharmacies, the primary purpose was the purchase of cosmetic-related products, such as treatments for hair loss, skincare, or obesity (49.0%, 49/100), reflecting a significant difference in the purpose of telemedicine visits between hospitals and pharmacies (p < 0.001). This difference in usage trends showed statistically meaningful variations among doctors and patients (p < 0.001) and pharmacists and patients (p < 0.001).

Time required for telemedicine

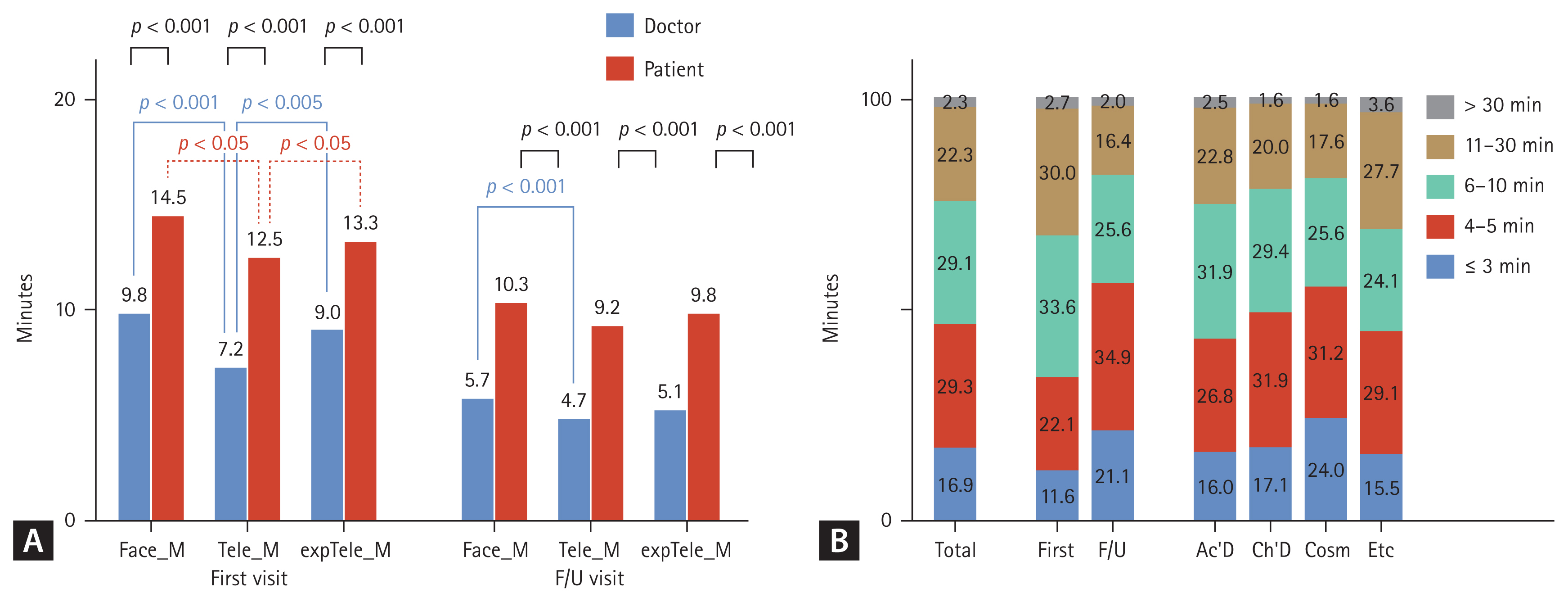

Among doctors, the time required for telemedicine was significantly shorter than that for both first visits (7.2 ± 4.8 minutes vs. 9.8 ± 5.0 minutes, p < 0.001) and follow-up visits (4.7 ± 5.7 minutes vs. 5.7 ± 5.7 minutes, p < 0.001) when compared to face-to-face treatment (Fig. 2A). This trend was consistent with patient responses. For first visits, the treatment time perceived as appropriate by patients was significantly longer than that perceived by doctors (13.3 ± 9.2 minutes vs. 9.0 ± 5.0 minutes, p < 0.001). A similar trend was observed for repeat visits (9.8 ± 7.9 minutes vs. 5.1 ± 3.3 minutes, p < 0.001). Both doctors and patients perceived telemedicine to require less time than the actual average face-to-face consultation time during first visits (all p < 0.001). Regarding actual treatment times, the most common duration for patients during first visits was 6–10 minutes (221/657 respondents), while for follow-up visits, it was 4–5 minutes (294/843 respondents) (Fig. 2B). For acute mild conditions such as colds and fevers, the most common treatment duration was 6–10 minutes (192/601 respondents). For chronic conditions such as hypertension or diabetes, the most frequent treatment duration was 4–5 minutes (158/496 respondents). Notably, 24.0% of respondents who used telemedicine for purposes such as “hair loss/beauty” reported treatment times of ≤ 3 minutes, shorter compared to respondents using telemedicine for other purposes.

Time required for telemedicine. (A) Time spent on telemedicine from the perspectives of doctors and patients. (B) Time required for telemedicine by disease type. Ac’D, acute disease; Ch’D, chronic disease; Cosm, cosmetic; Etc, etcetera; expTele_M, expected time for telemedicine; Face_M, face-to-face treatment; First, first visit; F/U, follow-up visit; min, minutes; tele_M, telemedicine.

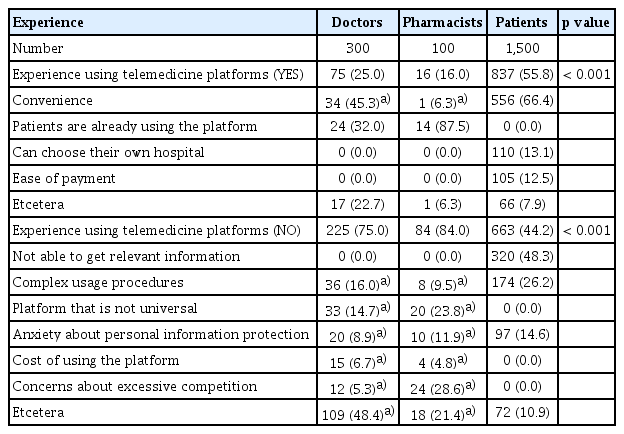

Utilization of platforms in telemedicine

Regarding telemedicine platforms, both doctors and pharmacists often lacked experience using them (75.0% vs. 84.0%, p = 0.063) (Table 3). The reasons for platform use differed significantly between doctors and pharmacists (p < 0.001). For doctors, the primary reason was the convenience of the treatment process, including reservations, waiting, and information management (45.3%, 34/75). In contrast, pharmacists primarily used platforms because patients were already using them (87.5%, 14/16). Among patients using the platform, the primary advantages were the ease of making reservations (66.4%, 556/837), the ability to choose hospitals directly (13.1%, 110/837), and the convenience of paying medical expenses (12.5%, 105/837). When conducting telemedicine without platforms, doctors often cited platform complexity (16.0%, 36/225) or lack of universal adoption (14.7%, 33/225). Pharmacists, however, frequently expressed concerns about excessive competition on the platform (28.6%, 24/84) and the lack of widespread platform use (23.8%, 20/84). These differences in reasons for not using platforms were significant between doctors and pharmacists (p < 0.001). For patients, the main barriers to platform use were insufficient information about platforms (48.3%, 320/663) and complex usage procedures (26.2%, 174/663).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that the telemedicine pilot project in Korea was successfully implemented. It was established without major concerns, distrust, or issues. Notably, the majority of surveys were conducted in the internal medicine and family medicine departments. This focus aligns with the nature of these specialties, where face-to-face treatment is less frequently necessary, such as in chronic disease management, follow-ups, and consultations [17]. Considering that most telemedicine services provided by doctors involve pharmaceutical prescriptions, these results appear reasonable. Given current medical infrastructure and patient needs, internal medicine and family medicine seem to be the most appropriate entry points for telemedicine. This provides a basis for developing protocols or guidelines [18], addressing challenges, and establishing best practices for wider adoption.

A key advantage of telemedicine is enabling patients to manage their health without visiting hospitals [19,20]. From this perspective, doctors’ motivation to participate in telemedicine to ensure continuous monitoring and management of patients with chronic diseases is highly significant. This reflects the potential for health management at the doctor’s discretion without necessitating hospital visits [18,19]. The finding that patients primarily use telemedicine for managing chronic or mild conditions supports its positive direction. However, as patient demand for telemedicine grows, its operation requires careful consideration. While some patients may request telemedicine due to perceived good health, others who avoid hospital visits irrespective of their actual health condition may heavily rely on telemedicine. Therefore, when introducing telemedicine, it is essential that it be doctor-led to minimize potential problems [18,21]. In the case of non-face-to-face consultations (teleconsultations) conducted by pharmacists independently of doctors, the largest proportion of cases involved hair loss treatments (e.g., hair growth products) and beauty-related treatments or management (e.g., acne, obesity). For “hair loss and beauty treatments and management,” where treatments are often non-covered and less urgent, concerns arise regarding excessive treatment, unnecessary drug prescriptions, and increased risks of side effects. Notably, in this study, 24.0% of telemedicine consultations for hair loss and cosmetic purposes were completed within three minutes, suggesting potential deviations from telemedicine’s intended purpose. Following the implementation of the telemedicine pilot project, it is crucial to determine whether telemedicine will focus on health management or prioritize patient convenience. Establishing institutional safety measures is essential to address this issue.

Many believe telemedicine requires less time than face-to-face treatment, citing shorter interview times and reduced overall time due to communication limitations. However, paradoxically, the time deemed appropriate for telemedicine consultations is reportedly longer than the actual consultation time. This discrepancy arises because, although direct consultation time is shorter, administrative tasks outside consultation hours and associated personnel costs have increased [18,22,23]. For instance, more time is needed to prepare for treatment, including verifying patient eligibility and setting up equipment. Technical challenges also arise, such as issuing prescriptions, addressing patient questions about the telemedicine system, and managing unstable connections. Moreover, while the absence of physical examinations like auscultation, percussion, and palpation may reduce consultation time, it often necessitates more detailed inquiries to assess the patient’s condition through other means. Therefore, a cautious approach to telemedicine is vital, especially in cases where physical examination is critical. This underscores the need for comprehensive policies, including guidelines and protocols, to address these challenges effectively in the future.

Recently, telemedicine platforms have proliferated to the extent that the term “platform war” has been coined [24]. These platforms aim to reduce administrative time outside treatment hours, as well as the time and cost associated with personnel management [25]. The role of such platforms in telemedicine is significant [19,21,26]. However, most participants in this study reported no experience using platforms specifically designed for telemedicine. Notably, this telemedicine approach often involves issuing simple, repeated drug prescriptions rather than maintaining patient health care, which contradicts telemedicine’s intended purpose. The 2024 telemedicine pilot project guidelines stipulate video consultations as the primary method, with voice-only consultations permitted only when video consultations are not feasible. Consequently, adopting disease-specific platforms capable of managing various administrative tasks is preferable to implementing only a basic video consultation system. Institutions should establish strategic goals regarding target diseases and the conduct of telemedicine [18,20,27], utilizing devices or platforms aligned with these objectives [27]. While telemedicine should not be used solely for convenience, as highlighted by this study, platforms can improve the treatment process (e.g., reservations, waiting times, guidance) for doctors and the dispensing process (e.g., waiting times, guidance) for pharmacists. A frequently cited reason for not using platforms in this study was their complexity, which requires attention. The telemedicine guidelines primarily recommend video consultations [5], suggesting that doctors frequently utilize the platform. In contrast, pharmacists tend to have a lower frequency of platform usage, as most prescriptions are received via fax. Furthermore, many patients continue to visit pharmacies in person with physical prescriptions, indicating that pharmacists are not actively engaged with the platform in practice. Ultimately, platforms are expected to play a central role in telemedicine, and despite the concerns identified in this study, their universal adoption is anticipated in the near future [27]. As consistently emphasized, developing specialized platforms led by doctors and pharmacists remains essential because telemedicine should prioritize managing patient health over merely improving patient access convenience.

Currently, pharmacists in telemedicine are primarily involved in dispensing and providing medication guidance, highlighting the need for broader experience and analysis in this area. As telemedicine becomes more widespread, pharmacists will require opportunities to monitor patients’ medication compliance and effectiveness in managing chronic diseases, as well as to provide support through remote consultation [28,29]. However, under the current telemedicine system, offering follow-up consultation services to evaluate treatment progress, side effects, and patient satisfaction remains challenging. Introducing remote pharmacy services should be positively considered. Efforts are needed to transition pharmacists from a dispensing-centered role to active participants in patient management through telemedicine [30,31]. To achieve this, a system that enables continuous patient management in practice must replace platforms that focus solely on patient convenience [32]. The issue of drug delivery after telemedicine, a recent topic of discussion, may offer some positive aspects. However, challenges such as misdelivery and unresolved legal issues during the delivery process must be addressed.

As a survey-based study, this research has certain limitations. First, the survey was primarily conducted in internal medicine and family medicine departments. While these departments do not represent the entire medical specialty field, this study realistically reflects the current status of telemedicine following the telemedicine pilot project. Thus, it provides valuable real-world data for analyzing future medical policies and progress. Additionally, because the telemedicine pilot project is a significant issue in Korea, response bias may arise, with respondents potentially providing socially acceptable answers rather than their true opinions. If telemedicine is perceived as primarily a convenience rather than a means of health treatment and disease management, it may result in misguided policies regarding chronic disease management, necessitating caution. Furthermore, the question regarding consultation time in telemedicine may introduce recall bias, as it relies on the respondent’s memory. Although the platform could have clearly confirmed the time, verifying all past records within the survey was not feasible. To address this limitation, future research should incorporate more detailed questions regarding telemedicine experiences and satisfaction. By gaining insights into the specific diseases targeted, the methods used, and the scope of services provided, a more accurate analysis of telemedicine for particular conditions can be achieved. Additionally, breaking down the time required for telemedicine into detailed components could help identify its economic effectiveness. In situations where treatment occurs remotely but dispensing remains face-to-face, improving prescription delivery methods (e.g., receipt by a guardian or fax) is essential. Such improvements would provide valuable data for enhancing the telemedicine user experience. Conducting surveys to address platform complaints or determine the most suitable telemedicine practices for specific diseases—by aligning platforms, communication methods, and treatment durations with disease types—could help identify optimal treatment strategies.

Based on the results of this study, efforts are needed to enhance communication between patients and doctors or pharmacists and improve treatment accuracy in telemedicine. Telemedicine saves time, provides convenience, and is particularly useful for managing mild and chronic diseases. However, concerns persist regarding the brevity of patient communication and diagnostic accuracy in telemedicine, which may negatively affect care quality. To address these issues, developing evaluation indicators to strengthen telemedicine safety is essential, as is establishing a system for continuous monitoring and management. Before advancing telemedicine focused on convenience, specific data on medical accidents must be collected and analyzed to develop practical measures for preventing such incidents.

KEY MESSAGE

1. The research aimed to assess the potential for sustainable telemedicine systems by analyzing satisfaction levels, usage patterns, and the perceived benefits and challenges of telemedicine services.

2. The findings highlight significant differences in motivations and usage preferences among the three groups. For example, while patients valued telemedicine for its convenience and time-saving benefits, doctors and pharmacists emphasized the need for more effective chronic disease management.

3. This study underscores the gap in platform adoption and varying treatment times for different medical conditions and provides novel insights into how telemedicine services can be better institutionalized by addressing user-specific needs.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Yeryeon Jung: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, visualization; Hyunah Kim: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, visualization; Jeong-Yeon Kim: data curation, formal analysis; Seongwoo Seo: data curation, formal analysis; Youseok Kim: data curation, formal analysis; Min Jung Ko: writing - review & editing; Hun-Sung Kim: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, software, writing - review & editing, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency in South Korea (grant no. NECA-A-23-016, NECA-A-24-005).