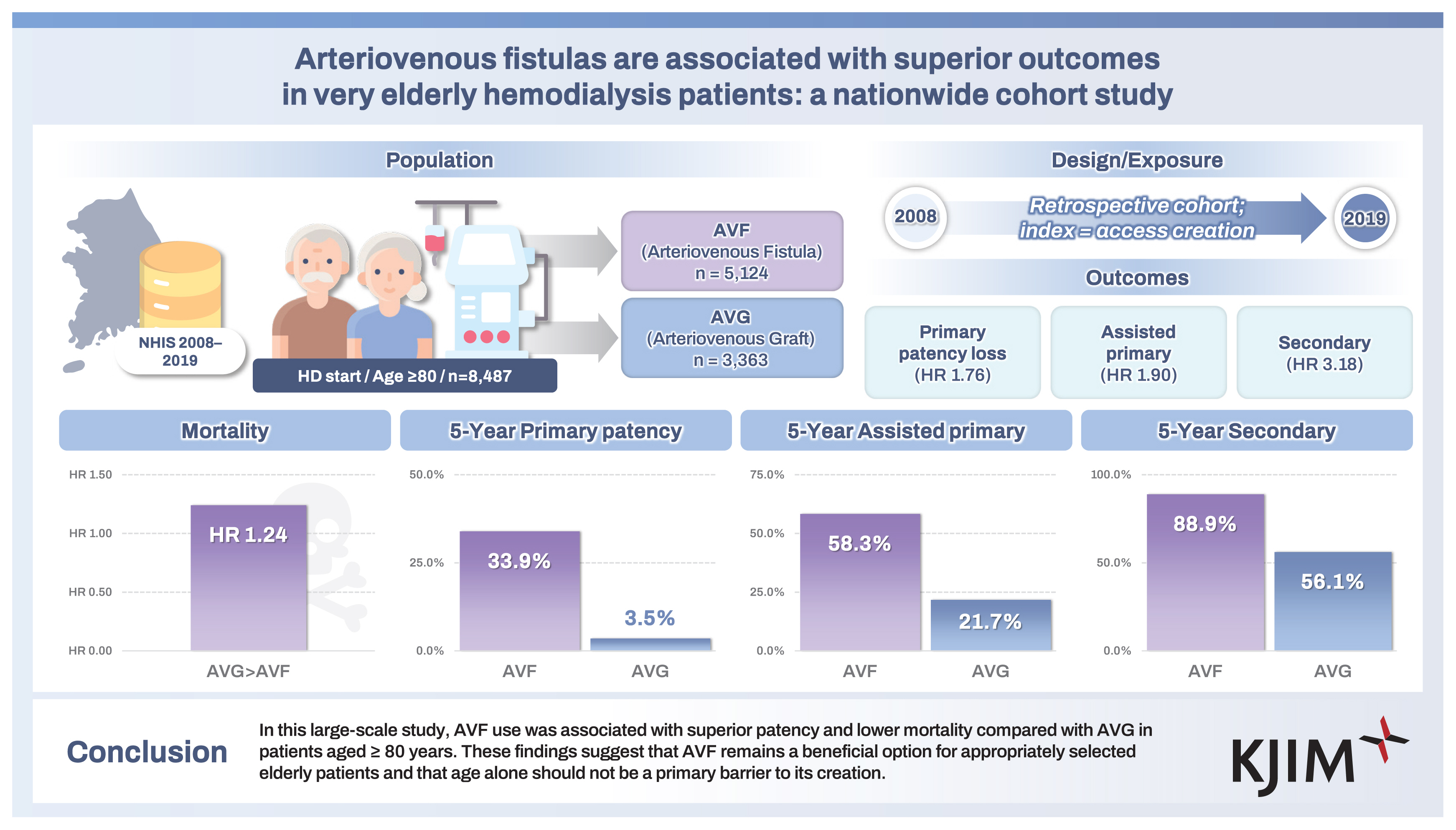

Arteriovenous fistulas are associated with superior outcomes in very elderly hemodialysis patients: a nationwide cohort study

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

The optimal vascular access strategy for very elderly patients initiating hemodialysis (HD) remains unclear. Arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) offer long-term benefits but may be limited due to vascular aging. This study evaluated vascular access outcomes in patients aged ≥ 80 years.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service between 2008 and 2019. Patients aged ≥ 80 years who initiated HD with a newly created AVF or arteriovenous graft (AVG) were included. Primary outcomes were primary, assisted primary, and secondary patency. The secondary outcome was all-cause mortality. Outcomes were compared using Kaplan–Meier analysis and multivariable Cox regression.

Results

Among 8,487 patients, 5,124 (60.4%) received AVFs (AVF group) and 3,363 (39.6%) received AVGs (AVG group). AVFs were associated with significantly lower rates of patency loss across all definitions. The adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for AVG vs. AVF were 1.76 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.67–1.86) for primary patency loss, 1.90 (95% CI, 1.77–2.03) for assisted primary, and 3.18 (95% CI, 2.81–3.61) for secondary patency loss. All-cause mortality was also higher in the AVG group (adjusted HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.17–1.30).

Conclusions

In this large-scale study, AVF use was associated with superior patency and lower mortality compared with AVG in patients aged ≥ 80 years. These findings suggest that AVF remains a beneficial option for appropriately selected elderly patients and that age alone should not be a primary barrier to its creation.

INTRODUCTION

The global rise in life expectancy has led to a growing number of elderly patients initiating dialysis, posing unique challenges in their clinical management [1,2]. In Korea, recent data from the Korean Renal Data System (KORDS) showed that over half of all incident dialysis patients were ≥ 65 years of age, with a significant and continuing increase in the population aged ≥ 80 years [3]. Vascular access (VA) remains a critical determinant of dialysis adequacy, complications, and survival, yet the optimal VA strategy in the very elderly remains controversial.

Arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) have long been considered the preferred access modality due to superior long-term patency, lower infection risk, and reduced mortality compared with arteriovenous grafts (AVGs) or central venous catheters (CVCs) [4]. However, in elderly populations, particularly octogenarians, AVF maturation is often delayed or unsuccessful due to age-related vascular changes and comorbidities such as diabetes and peripheral artery disease. In a seminal study of older adults, Lok et al. [5] reported that maturation failure accounted for ~49% of AVF failures—comparable to thrombosis/stenosis (43.9%)—highlighting the unique challenges of AVF creation in this age group. These limitations have raised concerns regarding the universal applicability of the “Fistula First” initiative in older adults [4,6–10].

This issue has been examined in several studies with mixed findings. While some reports suggest comparable or even favorable outcomes with AVFs in elderly patients when preoperative assessment is thorough and vessel quality is adequate [5,11–13], others highlight high failure rates and prolonged catheter dependence, particularly in frail or comorbid individuals, were reported in other studies [6,14–16]. Recent guidelines, including the 2019 Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) VA update, advocate for a “Patient First” approach, emphasizing individualized access planning based on life expectancy, functional status, vascular anatomy, and patient preference [9,10,17].

Despite increasing attention, real-world data on VA outcomes in patients ≥ 80 years of age remain limited, especially from East Asian populations. Furthermore, few studies have simultaneously evaluated both patency metrics and survival outcomes across different VA types in this age group.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine whether, among Korean patients aged ≥ 80 years initiating hemodialysis (HD), creation of AVF is associated with superior vascular patency and overall survival compared with AVG. We hypothesized a priori that AVF would confer longer vascular patency as well as lower all-cause mortality, than AVG in this very elderly population. Our findings aim to inform clinical decision-making and support individualized VA strategies for the very elderly.

METHODS

Data sources and study population

This study utilized data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database between January 2008 and December 2019. The dataset includes demographic information, ICD-10 diagnostic codes, procedure codes, prescription records, inpatient and outpatient claims, and mortality data. Lifestyle factors such as smoking status, alcohol consumption, and basic laboratory values were obtained from the national health screening database.

The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 2020-0576) of Asan Medical Center, and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design. All procedures adhered to national regulations and ethical standards.

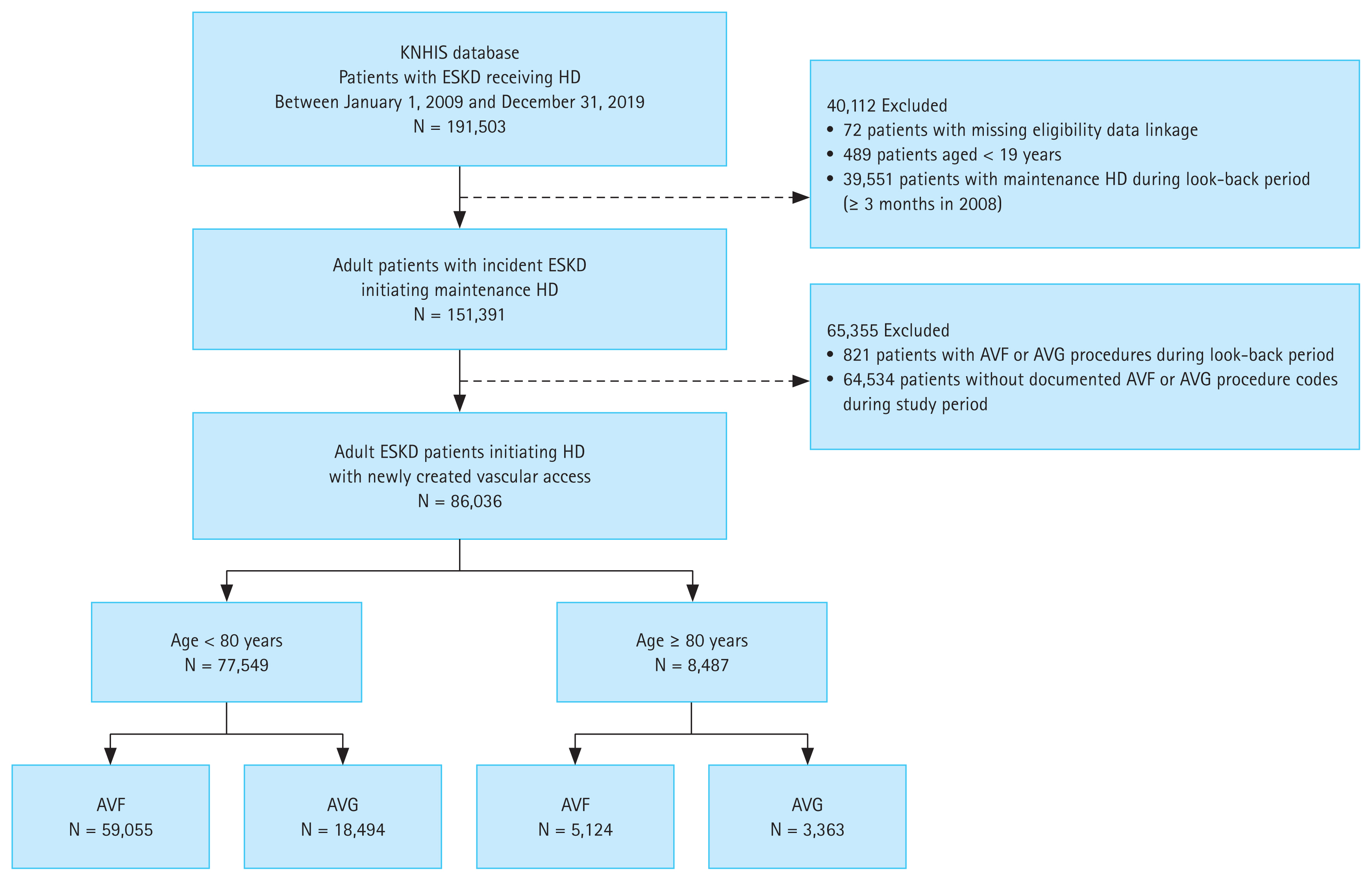

We identified patients diagnosed with end-stage kidney disease who received maintenance HD using a three-part algorithm to enhance specificity. First, individuals were required to have the Korean Rare and Intractable Disease special-exemption code V001, which is issued to patients certified as requiring maintenance HD. Second, we required at least one diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (ICD-10 code N18) during the ascertainment window. Third, to confirm ongoing treatment and reduce misclassification, we required ≥ 2 claims for HD procedures (O7020, O7021, or O9991) recorded at least 90 days apart after the index date. The cohort explicitly includes patients who may have initiated dialysis with a CVC before receiving their permanent access. Patients with evidence of peritoneal dialysis (V003) or kidney transplantation (V005, R3280, or Z94.0) before or within 90 days of the index date were excluded. We also excluded those who had undergone HD or VA creation during the look-back period (calendar year 2008), younger than 19 years, or had received HD for ≥ 3 months prior to the index date. This combined approach is a standard and validated method in claims-based research to minimized the inclusion of patients with acute kidney injury or non-dialysis CKD [18–20]. A visual summary of cohort selection is presented in Figure 1.

Study cohort selection process. Flow diagram of patient selection from the Korean NHIS database, identifying adult ESKD patients initiating HD with newly created AVF or AVG. NHIS, National Health Insurance Service; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; HD, hemodialysis; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft.

Clinical variables and risk factors

Comorbidities were identified using ICD-10 codes recorded within one year before the index date. Hypertension was defined using I10 and diabetes mellitus using E10 or E11. Cardiovascular conditions included coronary artery disease (I21, I22), peripheral vascular disease (I70, I73), and cerebrovascular disease (I63–I66, I678). Dyslipidemia was defined using E78, and cancer was identified based on site-specific malignancy codes. These definitions were consistent with those used in our prior NHIS-based study [21].

Baseline use of antithrombotic agents was identified using Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes. Novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) were captured with B01AE07 (dabigatran) and B01AF sub-codes (rivaroxaban, apixaban and edoxaban), antiplatelet agents with B01AC, and warfarin with B01AA03.

The type of the facility in which each index HD claim was generated was obtained from the provider classification code that accompanies every NHIS claim. We collapsed the original codes into three categories: tertiary hospital (code 01), general hospital (code 11) and others (including hospital, clinic and community health center).

Age was categorized into four groups: 18–64, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥ 85 years. Health behavior variables such as body mass index (BMI), smoking, and alcohol use were obtained from the national health screening data. Because these variables had > 60% missingness in this very elderly, incident HD cohort, we used a three-model adjustment strategy: Model 1 (age, sex), Model 2 (Model 1 + comorbidities and care-setting variables including hospital type; excluding BMI, smoking, alcohol), and Model 3 (Model 2 + BMI, smoking, alcohol modeled categorically with an explicit “Not available” level). We did not perform multiple imputation due to the extent and likely non-random missingness in screening-derived variables. This approach aligns with recommended transparent reporting of missing-data handling in studies using routinely collected health data.

Definition of VA type

VA type was determined using initial procedure codes for AVF (O2011, O2012, O2081) or AVG (O2082). The index date was defined as that of initial VA creation. If both AVF and AVG codes were recorded on the same date, the case was classified as AVG. Only patients with clearly documented access creation codes were included in the final cohort.

Assessment of study outcomes

The primary outcomes were VA-related patency measures. The definitions of patency were based on the KDOQI guidelines [17]. Primary patency was defined as the time from access creation to the first occurrence of thrombosis or any intervention to maintain or restore patency. Assisted primary patency was defined as the time from access creation to access thrombosis. During this interval, interventions intended to maintain patency were allowed without counting as failure. Secondary patency was defined as the time to permanent access abandonment, operationalized as either the creation of a new access or the placement of a tunneled dialysis catheter (O7011–O7014) with no subsequent removal within one year. Catheter placement alone did not count as loss of primary or assisted primary patency. Temporary catheterization followed by catheter removal was considered maintenance of patency provided the original access remained in use. We did not systematically quantify the frequency or duration of CVC exposure as a covariate or outcome. Catheter procedure codes were used solely to operationalize outcome definitions.

To identify these outcomes, we used procedural codes for percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (procedure code: M6597), thrombectomy (M6632, M6633, M6639), surgical thrombectomy or revision (O2083), and percutaneous stent placement (M6605, M6613). Procedure codes for new access creation (O2011, O2012, O2081, O2082) were also used. To minimize misclassification of non-HD-related procedures, fistulography codes (HA731, HA711, HA712, HA732, HA643) were used to exclude unrelated vascular interventions such as interventions for renal arteries or iliofemoral arteries.

The secondary outcome was all-cause mortality, determined using NHIS death records. Patients were censored at the first of death, outcome event, transition to peritoneal dialysis (O7061, O7062, O7071, O7072), kidney transplantation (Z940), or end of the study period (December 31, 2019).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and as means with standard deviations for continuous variables. Group comparisons were performed using Pearson’s chi-square test or Student’s t-test/ANOVA, as appropriate.

Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate VA patency and overall survival, with differences assessed using the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the associations between access type and outcomes. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

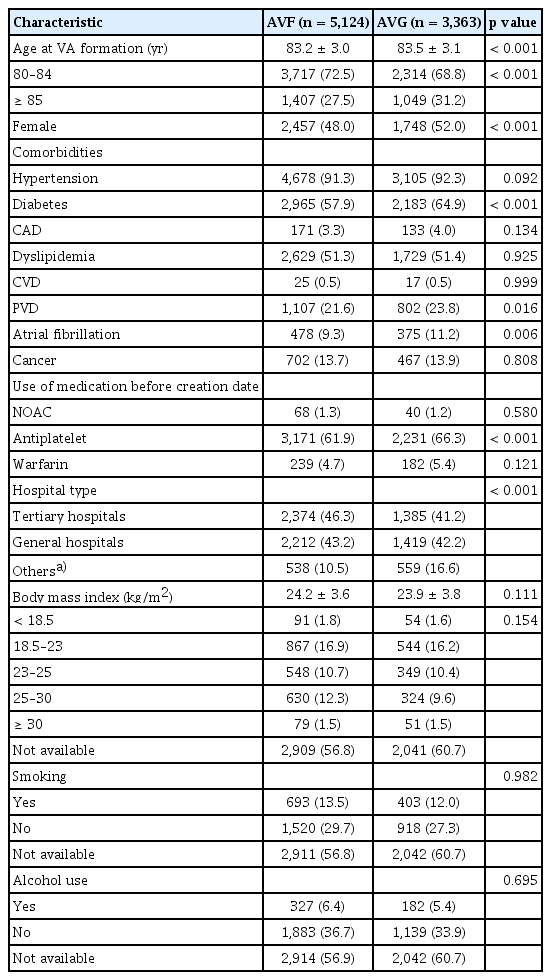

Baseline characteristics of elderly HD patients

The baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Among the 8,487 patients aged ≥ 80 years who initiated HD with newly created VA, 5,124 (60.4%) underwent AVF creation (AVF group) and 3,363 (39.6%) underwent AVG placement (AVG group). The mean age at the time of VA formation was significantly higher in the AVG group compared with the AVF group (83.5 vs. 83.2 years, p < 0.001). Females were more likely to undergo AVG placement than AVF creation (52.0% vs. 48.0%, p < 0.001).

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (64.9% vs. 57.9%, p < 0.001), peripheral vascular disease (23.8% vs. 21.6%, p = 0.016), and atrial fibrillation (11.2% vs. 9.3%, p = 0.006) was significantly higher in the AVG group than in the AVF group. Patients in the AVG group were also more likely to have received antiplatelet therapy prior to access creation than subjects in the AVF group (66.3% vs. 61.9%, p < 0.001). Other clinical variables, including BMI, smoking status, and alcohol consumption, were comparable between the two groups. AVF procedures were more frequently performed at tertiary hospitals compared with AVG placement (46.3% vs. 41.2%).

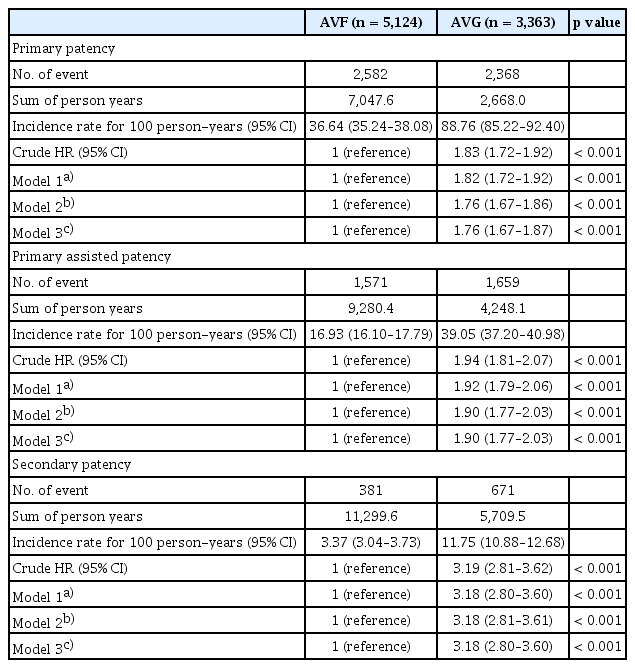

Comparison of patency outcomes between AVF and AVG

Among patients aged ≥ 80 years, AVF creation was associated with significantly better VA outcomes across all patency definitions. The incidence rate of primary patency loss was 36.64 per 100 person-years in the AVF group compared with 88.76 in the AVG group. Adjusted estimates are from our prespecified primary model (Model 2). Estimates were similar in Model 3 that additionally included BMI, smoking, and alcohol (Table 2). After adjusting for relevant covariates, the HR for primary patency loss with AVG vs. AVF was 1.76 (95% CI, 1.67–1.86; p < 0.001). Similar associations were observed for assisted primary patency (adjusted HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.77–2.03) and secondary patency (adjusted HR, 3.18; 95% CI, 2.81–3.61), indicating consistently superior durability of AVFs in this population (Table 2). Effect estimates from Model 3 (including BMI, smoking, alcohol) were directionally consistent with the primary Model 2 results, supporting robustness to missing lifestyle data.

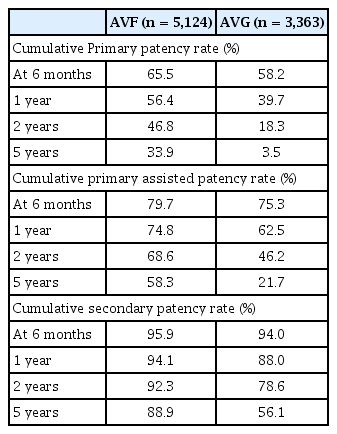

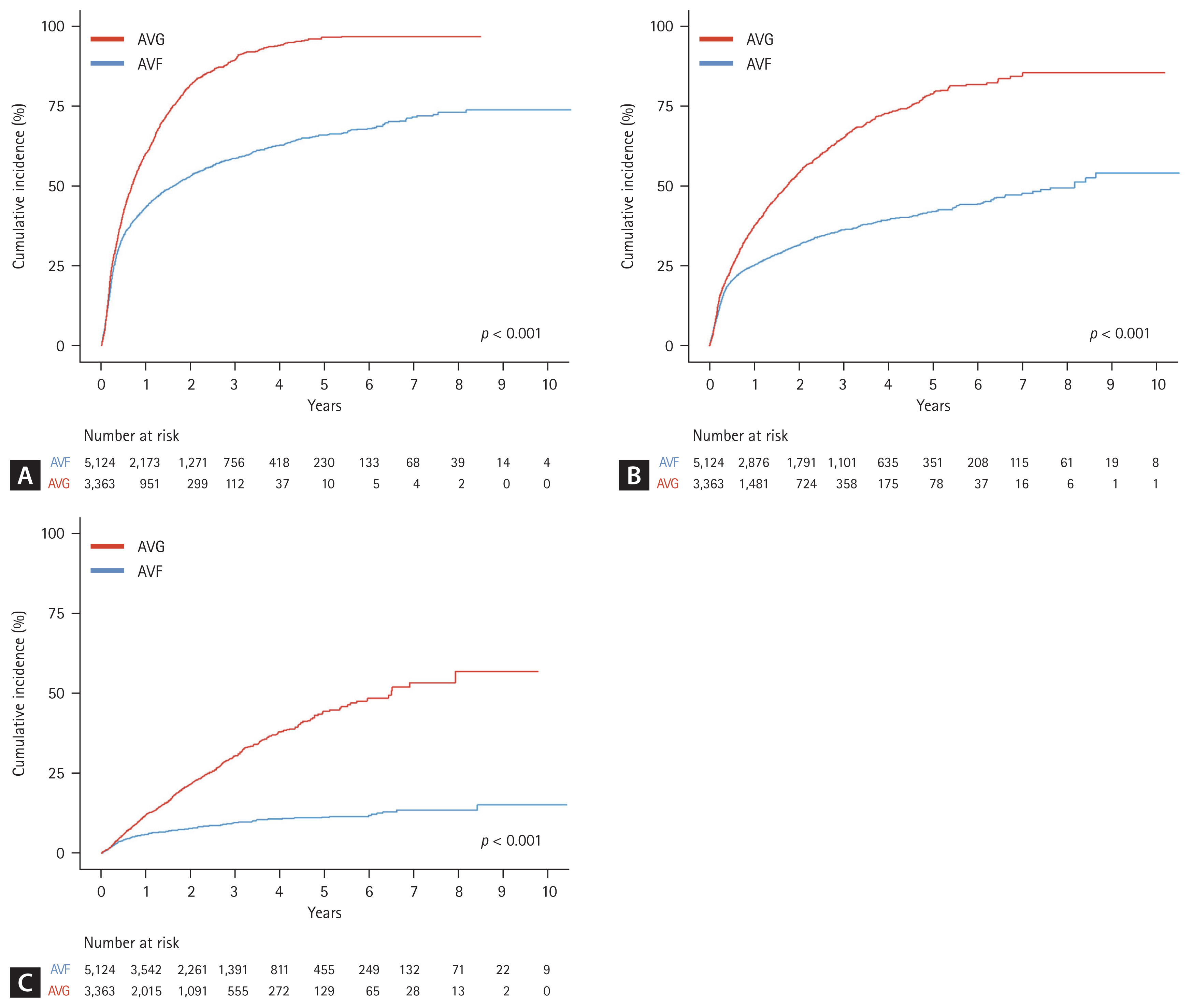

Cumulative patency rates over time

Cumulative patency analysis further demonstrated the long-term advantages of AVF. At one year, the primary patency rate was 56.4% in the AVF group and 39.7% in the AVG group. At five years, these rates had declined to 33.9% and 3.5%, respectively. For assisted primary patency, the five-year cumulative rate was 58.3% for AVF compared with 21.7% for AVG. Secondary patency at five years remained markedly higher in the AVF group (88.9%) than in the AVG group (56.1%). These cumulative rates are presented in Table 3 and visualized in Figure 2.

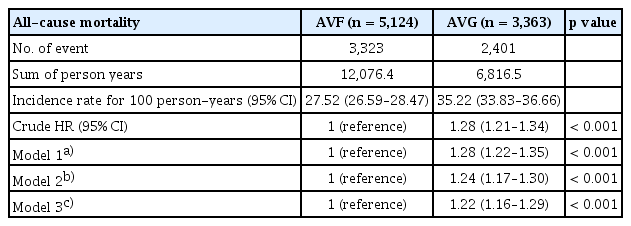

All-cause mortality

All-cause mortality was also significantly higher among patients with AVG. The incidence rate of death was 35.22 per 100 person-years in the AVG group compared with 27.52 in the AVF group. After adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics, AVG use remained independently associated with an increased risk of death (adjusted HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.17–1.30; p < 0.001; Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This large, nationwide cohort study demonstrates that in Korean patients aged ≥ 80 years, AVF was associated with substantially better patency and lower all-cause mortality than AVG. This association remained robust after multivariable adjustment, reinforcing the clinical benefit of AVF in the very elderly. Several factors may explain the superior outcomes observed with AVF in our cohort of patients aged ≥ 80 years. In Korea, early nephrologist referral and routine use of vascular mapping, often guided by ultrasound, are common practices that may allow selective AVF creation in patients with favorable vascular anatomy [22–25]. Furthermore, patients undergoing AVF creation may have better overall functional and nutritional status, contributing to both access durability and survival. In addition, center-level practices such as multidisciplinary access planning and routine surveillance protocols may support higher AVF patency [26]. Cultural and systemic factors including more frequent follow-up and longer hospitalization periods may also have facilitated early intervention for access-related complications [27].

The results align with prior studies showing AVF benefits even in patients aged > 80 years [5,11–13]. For example, Olsha et al. [13] reported favorable long-term AVF patency in octogenarians when access was created based on careful preoperative evaluation. Similarly, a recent Portuguese cohort by Dias et al. [28] showed comparable AVF outcomes between elderly and younger patients when vascular mapping guided access planning. A recent meta-analysis of 12 studies including over 95,000 elderly HD patients found that AVFs were associated with significantly better overall survival (HR, 1.38), access survival (HR, 1.60), and lower infection risk (odds ratio [OR], 9.74) compared with AVGs [29]. However, AVFs also had a higher risk of maturation failure (OR, 0.33), highlighting the trade-off in VA planning in this population.

The superior outcomes in the AVF group are likely influenced by selection bias. Evidence for this includes the AVF group being younger with fewer comorbidities, such as diabetes. Furthermore, a non-statistically significant trend showed that patients with a higher BMI or a history of smoking and alcohol also received more AVFs. This paradox suggests that clinicians selected patients for AVF creation—even from higher-risk groups—based on better overall health and more favorable vascular anatomy. This patient selection is a critical, unmeasured confounder that likely contributed to the observed benefits of AVF.

Although we adjusted for key confounders, unmeasured factors related to access selection (e.g., vascular anatomy and vein quality, arterial calcification, pre-operative mapping, frailty, functional status, urgency of dialysis initiation, and surgeon/center preference) may remain. And these factors may bias comparisons between AVF and AVG. Therefore, while our findings favor AVF in very elderly patients, they should be interpreted with appropriate caution, and confirmation in prospective, clinically detailed cohorts is warranted.

Results in the literature remain controversial. Multiple reports highlight the challenges of AVF in elderly patients, including high rates of primary failure, delayed catheter-free dialysis, and early abandonment [14–16]. Meta-analyses also suggest increased failure rates of distal AVFs in the elderly, with better outcomes from proximal fistulas or AVGs in select cases [30,31]. Additionally, Lyu et al. [16] caution that prolonged catheter dependence with AVF planning may offset long-term benefits in older patients with limited life expectancy.

Importantly, our study provides further evidence that AVFs may confer meaningful survival advantages even among octogenarians. These findings remained robust even after adjusting for comorbidities and medication use, minimizing confounding. Although anatomical and individual factors must be considered, the results and data support prioritization of AVF whenever technically feasible in this population.

The strengths of this study include the large sample size, nationally representative population, and detailed long-term follow-up. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, outcomes were defined using administrative claims, which may be subject to misclassification. Second, anatomical and surgical factors such as vessel diameter, access location, or surgical technique were unavailable, limiting our ability to adjust for procedural complexity. Third, residual confounding cannot be fully excluded despite multivariable adjustment. BMI, smoking, and alcohol use which sourced from national screening were unavailable for a large fraction of this very elderly cohort, a known limitation of Korean NHIS screening data. To mitigate bias from extensive and likely non-random missingness, we prespecified Model 2 (excluding these variables) as primary and Model 3 as a sensitivity analysis with a missing category. While this pragmatic strategy preserves sample size and may capture informative missingness, estimates could be attenuated and residual confounding by lifestyle factors cannot be excluded. Fourth, and most importantly, this study is susceptible to selection bias. Despite multivariable adjustment, unmeasured factors that drive access selection could favor AVF outcomes. We therefore interpret the observed advantages of AVF with appropriate caution. Fifth, our study used nationwide NHIS database, which do not contain functional maturity information. Therefore, we could not directly distinguish maturation failure from other early failures. This constraint is shared by prior Korean claims-based vascular-access studies that have relied on procedure-based endpoints or catheter-dependence metrics rather than clinical maturation per se. Consequently, we report patency using standardized, code-based definitions and explicitly describe how catheter insertion events were handled. Lastly, we did not quantify the frequency or duration of CVC use within access groups. Because short-term catheterizations are common and inconsistently captured in claims, catheter procedure codes were employed solely to define secondary patency. As a result, we were unable to assess time-updated catheter status or its temporal relation to access events. Therefore, residual confounding by catheter exposure may persist and should be considered when interpreting our results.

In this nationwide cohort study of Korean patients aged ≥ 80 years initiating HD, AVF was associated with superior VA outcomes and lower all-cause mortality compared with AVG. While these findings should be interpreted with caution due to the potential for significant selection bias, they provide robust real-world evidence that AVF can be a durable and beneficial option in the very elderly. The results suggest that age alone should not be an absolute contraindication for AVF creation, and it should be considered a priority whenever technically feasible and clinically appropriate.

KEY MESSAGE

1. In patients aged ≥ 80 years, AVFs were associated with superior patency outcomes and lower all-cause mortality compared with AVGs.

2. These findings provide robust real-world evidence that AVFs should generally be preferred in the very elderly, particularly in Asian populations.

3. With appropriate preoperative evaluation and individualized planning, age alone should not be considered a barrier to AVF creation in this population.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Hyung Duk Kim: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, validation, writing - original draft; Do Hyoung Kim: methodology, data curation, formal analysis; Hyangkyoung Kim: methodology, resources, data curation, formal analysis, validation; Hyung-Seok Lee: validation, writing - review & editing, supervision; Seung Boo Yang: validation, supervision; Seok Joon Shin: writing - review & editing, supervision; Hoon Suk Park: conceptualization, writing - review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

This research was supported by a research grant of Korean society of dialysis access.