Effectiveness of low-dose mepolizumab in refractory eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: systemic steroid use and remission

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

This study investigated the clinical efficacy of low-dose mepolizumab (100 mg) in controlling severe eosinophilic asthma, aiming to induce eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) remission and reduce systemic steroid usage. Additionally, we constructed a basic frame for our longitudinal EGPA cohort by collecting serial blood samples before, during, and after mepolizumab treatment in EGPA patients.

Methods

We conducted a 2-year prospective observational cohort study in patients with uncontrolled severe eosinophilic asthma and refractory EGPA who used systemic steroids (≥ 7.5 mg/day of prednisolone) or other immunosuppressant drugs for at least 6 months. All patients were treated with 100 mg of mepolizumab every 4 weeks for 1 year to control severe eosinophilic asthma and then were followed for an additional 1 year to monitor their disease course. We analyzed total systemic steroid use and EGPA remission/relapse during the study period.

Results

Three EGPA patients were included in this study and completed 16 study visits over a 2-year period. After 1 year of treatment with mepolizumab (100 mg monthly), all 3 patients were able to reduce their maintenance dose of systemic steroids, with 2 patients completely discontinuing use. These 2 patients achieved EGPA remission during mepolizumab treatment, and their remission status remained stable for 1 year after they stopped receiving the medication.

Conclusions

Low-dose mepolizumab treatment demonstrated clinical efficacy in reducing the maintenance dose of systemic steroids required for severe refractory EGPA. While not all patients achieved EGPA remission with low-dose mepolizumab, some did, and their remission persisted even after treatment discontinuation.

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA) is a rare inflammatory disorder with heterogeneous phenotypes characterized by asthma, necrotizing vasculitis, extravascular granulomas, and blood and tissue eosinophilia [1–3]. The overall prevalence of EGPA ranges from 10.7 to 14 per million adults, with an annual incidence of 0.5 to 4.2 cases per million people. The mean age at diagnosis is 50 years, with a similar frequency in males and females [2]. Except for a few case studies or epidemiology studies, little is known about the clinical aspects of Korean EGPA patients [4,5].

A diagnosis of EGPA should be considered in patients with asthma, chronic rhinosinusitis, and eosinophilia who develop end-organ involvement, especially peripheral neuropathy; lung infiltrates; cardiomyopathy; or other organ involvement, such as skin, gastrointestinal, or kidney involvement [2]. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs), usually against myeloperoxidase, are detectable in 30–40% of cases and are associated with vasculitis manifestations, such as glomerulonephritis, neuropathy, and purpura. In contrast, ANCA-negative patients often exhibit cardiomyopathy and lung involvement [2]. EGPA evolves through 3 phases: prodromic allergic, eosinophilic, and vasculitic. The allergic phase can last several years and is marked by asthma and chronic rhinosinusitis. Eosinophilia and end-organ involvement appear during the eosinophilic phase, and vasculitis manifestations such as mononeuritis multiplex and glomerulonephritis are found in the vasculitic phase. However, these phases can overlap, and progression may not always follow the expected sequence [2].

The primary treatment for EGPA involves systemic steroids, as the pathogenesis largely revolves around eosinophils. Severe EGPA is defined by the presence of unfavorable prognostic factors, including components of the 5-factor score (renal insufficiency, proteinuria, cardiomyopathy, gastrointestinal tract involvement, and central nervous system involvement), peripheral neuropathy, and rare manifestations such as alveolar hemorrhage.

Glucocorticoids should be the initial therapy to induce remission in all newly diagnosed, active EGPA patients. For patients with severe features of EGPA, cyclophosphamide or rituximab should be added. Remission maintenance therapy also depends on the severity of EGPA symptoms. For those with severe manifestations, treatments like rituximab, mepolizumab, or disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are recommended alongside glucocorticoids as remission maintenance treatment. Conversely, patients whose EGPA presents with non-severe features may receive glucocorticoids alone or in combination with mepolizumab. In all cases, glucocorticoids should be tapered to the minimum effective dose to minimize complications [2].

Interleukin-5 (IL-5) plays a crucial role in the proliferation, maturation, and differentiation of eosinophils, and its levels are elevated in patients with EGPA [6,7]. Therefore, biologics targeting IL-5, such as mepolizumab, reslizumab, and benralizumab, are being explored as new treatment options for EGPA, with mepolizumab being the most well-known. The Mepolizumab in Relapsing or Refractory EGPA (MIRRA) study demonstrated benefits in extending remission and reducing glucocorticoid usage in participants treated for 1 year with a monthly dose of 300 mg of mepolizumab, 3 times the dosage used for severe eosinophilic asthma [6]. This led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to approve mepolizumab in 2017 as the first drug specifically for EGPA. Following this approval, several real-world clinical studies have examined the role of mepolizumab in decreasing systemic steroid use and potentially replacing other immunosuppressants [8–13]. However, the high cost of mepolizumab remains a significant barrier to its use in practice, as the approved dose for EGPA is 3 times higher than that for severe eosinophilic asthma. Consequently, some cohort studies and case reports have indicated that lower doses of mepolizumab (100 mg) may also be effective in treating EGPA, especially in reducing the need for systemic steroids and managing respiratory symptoms [8,13,14]. Additionally, other anti-IL-5 treatments, such as reslizumab and benralizumab, have shown similar clinical benefits in treating EGPA. In September 2024, the U.S. FDA approved benralizumab for treatment of EGPA based on results from the MANDARA study, a randomized, double-blind, active-controlled 52-week trial comparing its efficacy and safety to that of mepolizumab [11,15,16].

In this study, we investigated the clinical efficacy of low-dose mepolizumab (100 mg, as prescribed for severe eosinophilic asthma) in inducing remission in EGPA and reducing the need for systemic steroids. Additionally, we established a foundational framework for our longitudinal EGPA cohort, the first of its kind in Korea, by collecting serial blood samples.

METHODS

Study design

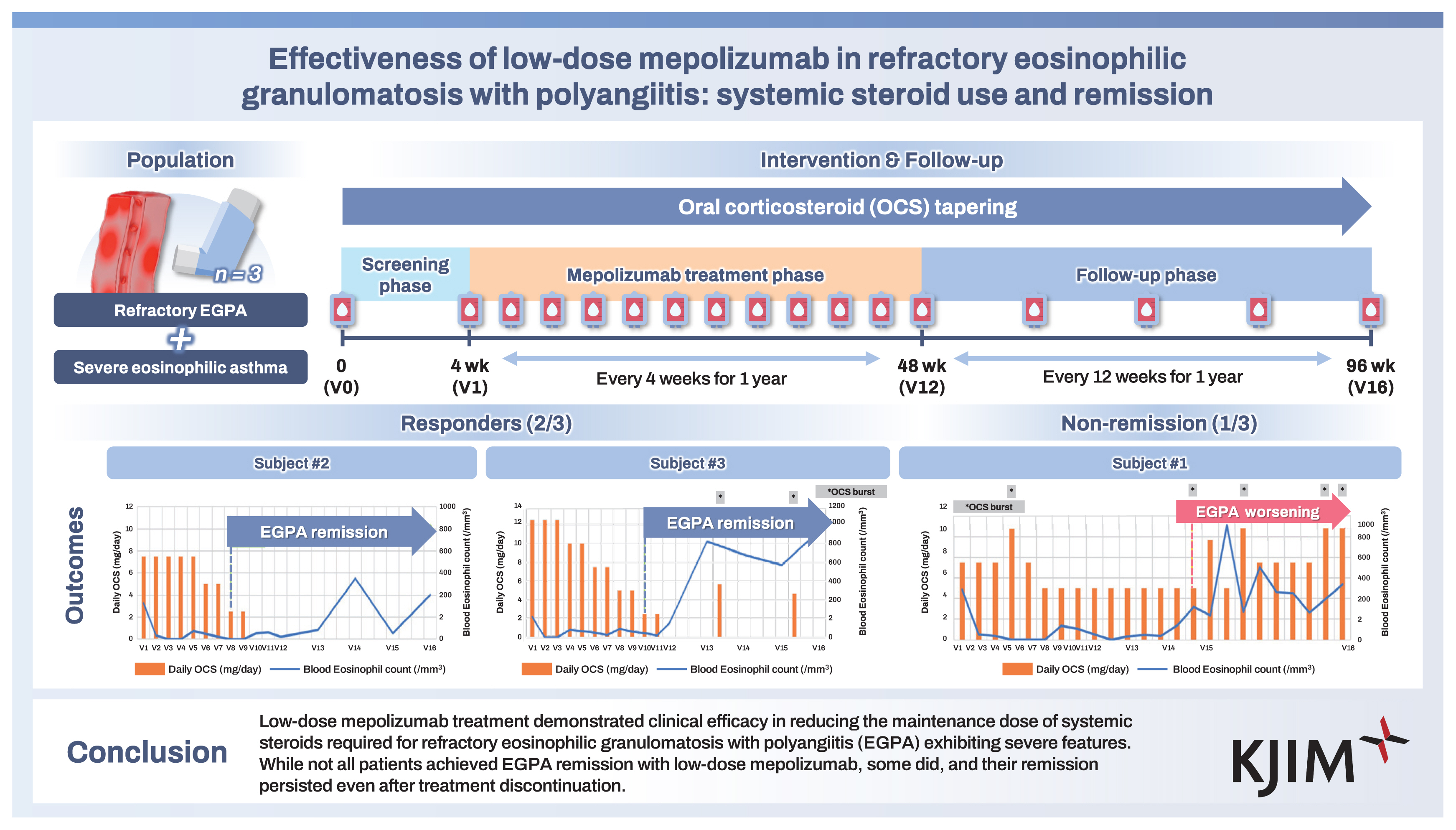

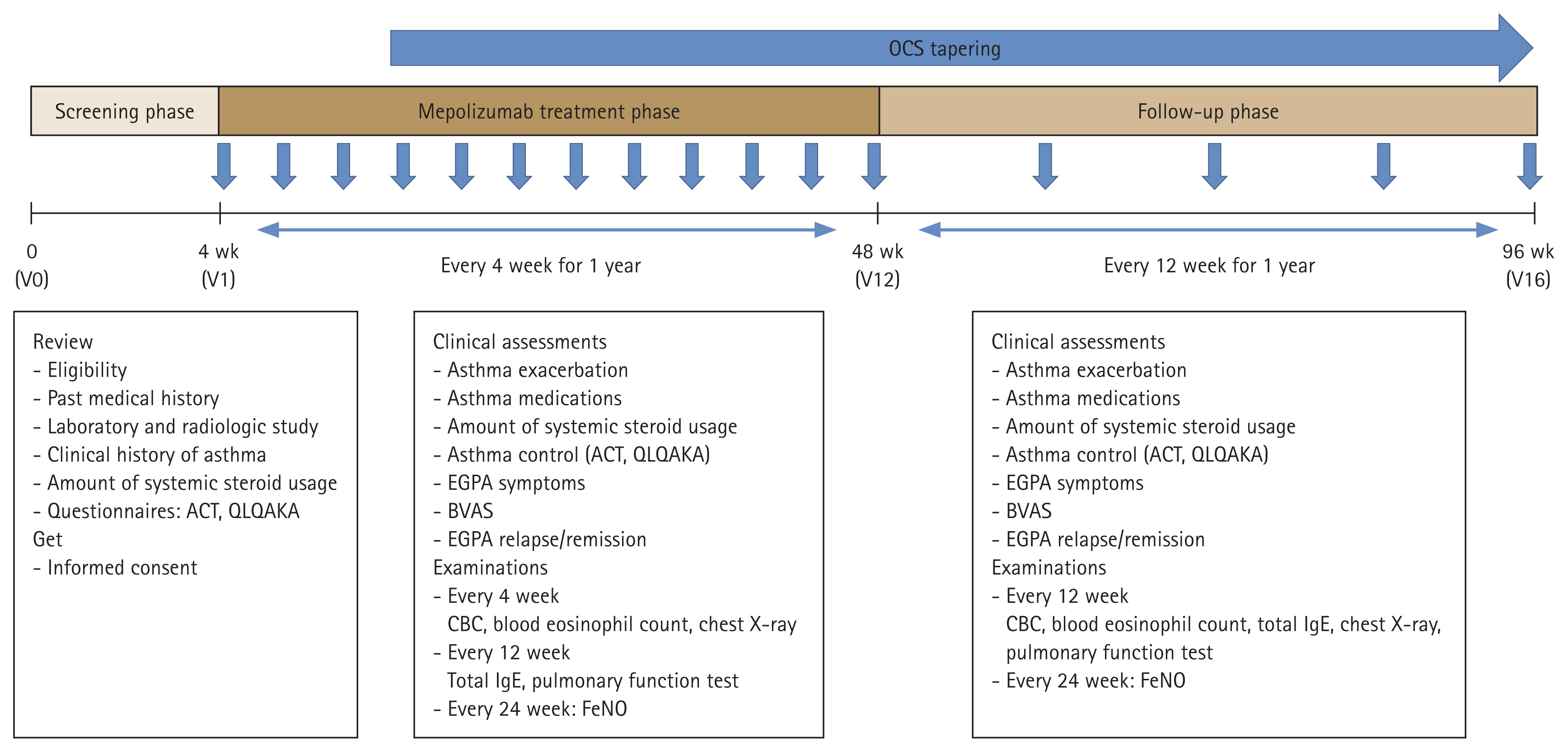

This prospective observational cohort study evaluated the effectiveness of 100 mg of mepolizumab in inducing remission in EGPA and in reducing the need for systemic steroids. The study design is illustrated in Figrue 1 and consisted of a screening phase, a mepolizumab treatment phase, and a follow-up phase. During the treatment phase (visit 1 [V1]–V12), participants visited our clinic every 4 weeks for mepolizumab administration. At each visit, the physician assessed the patient’s asthma and EGPA status and collected relevant clinical data.

Schematic of the study design. OCS, oral corticosteroid; V, visit; ACT, Asthma Control Test; QLQAKA, Quality of Life Questionnaire for Adult Korean Asthmatics; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; BVAS, Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score; CBC, complete blood count; IgE, immunoglobulin E; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide.

In the follow-up phase (V13–V16), patients returned to the clinic every 12 weeks for an additional 12 months for evaluation of those same parameters. Throughout the study, blood samples were collected for future investigations into biomarkers and omics analyses. The timing of the serial blood collections was before (V0/V1), during (V2, V3, V6, V9, V12), and after (V13, V14, V15, V16) mepolizumab treatment.

Study subjects

We included refractory EGPA patients with uncontrolled severe eosinophilic asthma who were older than 18 years and had taken EGPA remission maintenance treatments including a systemic glucocorticoid (≥ 7.5 mg/day of prednisolone) with or without immunosuppressant drugs (cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methotrexate, rituximab, mycophenolate, tacrolimus) for at least 6 months. A stable systemic glucocorticoid dose was required for inclusion in the screening phase, 4 weeks before the start of mepolizumab treatment. Informed consent was obtained from all eligible patients who agreed to participate in the study.

Patients who experienced organ-threatening or life-threatening EGPA within 3 months before screening were excluded from the study. Additionally, we excluded individuals who had used biologic drugs within 6 months prior to the screening phase or who had participated in another clinical trial involving asthma biologics.

Definitions of refractory EGPA and severe eosinophilic asthma

EGPA is defined by the following criteria: (1) a history or presence of asthma; (2) peripheral blood eosinophilia (proportion greater than 10% or absolute count of 1,000 cells/ mm3); and (3) histopathological evidence or 2 or more clinical criteria typical for EGPA, as adapted from the MIRRA trial [6]. The clinical criteria for EGPA were classified into major (neuropathy, pulmonary infiltrates or alveolar hemorrhage, cardiomyopathy, and glomerulonephritis) and minor (sinonasal abnormality, palpable purpura, and ANCA positivity) categories. To establish a clinical diagnosis of EGPA, a patient must exhibit 2 or more clinical criteria, including at least 1 major criterion. Refractory EGPA was defined as failure to attain remission or experienced symptom recurrence within 6 months of remission-inducing treatment [1].

Severe eosinophilic asthma is defined according to the Global Initiative for Asthma strategy [17]. Severe asthma is characterized as an uncontrolled state despite treatment with medium or high doses of inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta2-agonist (ICS/LABA), or as requiring high-dose ICS/LABA to maintain adequate symptom control and to reduce exacerbations. For treatment with mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma, the blood eosinophil count must exceed 150/μL at the start of treatment or have been greater than 300/μL within the previous 12 months to comply with the Korean FDA indication.

Clinical data collection

During the initial screening phase, we documented each patient’s medical history, including laboratory results, steroid usage, and asthma history (onset, duration, exacerbations, and medications). Patients completed the Asthma Control Test (ACT) and the Quality of Life Questionnaire for Adult Korean Asthmatics. Most clinical parameters related to severe asthma were sourced from the Precision Medicine Intervention in Severe Asthma study, a collaborative Korea–UK research project [18]. We also collected specific EGPA parameters of clinical diagnosis criteria; steroid or immunosuppressant use; rescue medication usage; blood eosinophil count; and symptoms of neuropathy, pulmonary infiltrates or alveolar hemorrhage, cardiomyopathy, glomerulonephritis, sinonasal abnormality, or palpable purpura.

Throughout the study, we regularly assessed clinical asthma parameters, including asthma control, exacerbation history, and medication use. Physicians evaluated the above EGPA symptoms and calculated the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS) during each visit. The BVAS was calculated using version 3, where scores for persistent disease range from 0 to 33 and those for new or worsening disease range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating higher severity of disease. According to the BVAS scoring rules, only disease manifestations attributable to active vasculitis are scored; manifestations resulting from other causes, such as infections or comorbidities, are not included.

During the mepolizumab treatment phase, we conducted laboratory examinations, including blood counts and chest X-rays, every 4 weeks and measured serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels and pulmonary function every 12 weeks. In the follow-up phase, participants visited every 12 weeks for ongoing assessments.

EGPA remission and relapse

EGPA status was assessed as relapse or remission based on EGPA symptoms, medication requirement, and BVAS [19]. According to the MANDARA trial, EGPA remission is defined as a BVAS of 0 and a systemic steroid dose less than 4 mg per day (equivalent to prednisolone) [1].

EGPA relapse occurs when 1 or more of the following conditions are present: active vasculitis (BVAS greater than 0), worsening asthma symptoms or signs with an increased ACT score, active nasal or sinus issues, increase in daily steroid dose to 4 mg or greater (equivalent to prednisolone) or an increase in immunosuppressants, or hospitalization due to EGPA. A major relapse is defined as any organ- or life-threatening EGPA event, a BVAS score increase greater than 6 (involving at least 2 organ systems), or hospitalization due to asthma or EGPA [1].

Calculation of systemic steroid usage and tapering protocol

The systemic steroid usage by each patient is expressed as the equivalent dose of prednisolone. To determine the daily steroid dose, the total amount of systemic steroids used was divided by the duration of follow-up. This calculation also included any administered steroid bursts.

The tapering protocol for steroids was established by the physician. Tapering typically commenced after 3 months of mepolizumab treatment, with a reduction of 2.5 mg every 2 months. This tapering was performed when there was no worsening of asthma or EGPA symptoms, the BVAS remained stable, and the blood eosinophil count was within the normal range (≤ 5% and 500/mm3).

Clinical outcome analysis

The primary outcome of this study was a reduction in the use of systemic steroids. We calculated the mean daily dose of steroids at each visit and evaluated the time points for both a 50% (half) and a 100% (complete) reduction in dosage. The secondary outcomes were remission of EGPA at 36 weeks and 48 weeks during the mepolizumab treatment phase and duration of EGPA remission. Additionally, we monitored for any relapses of EGPA throughout the entire study period. Due to the small sample size, all clinical data and outcome results were presented as descriptive variables.

Ethical issues

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of CHA Bundang Medical Center (CHAMC 2022-01-006-011), and all participants provided written informed consent upon enrollment.

RESULTS

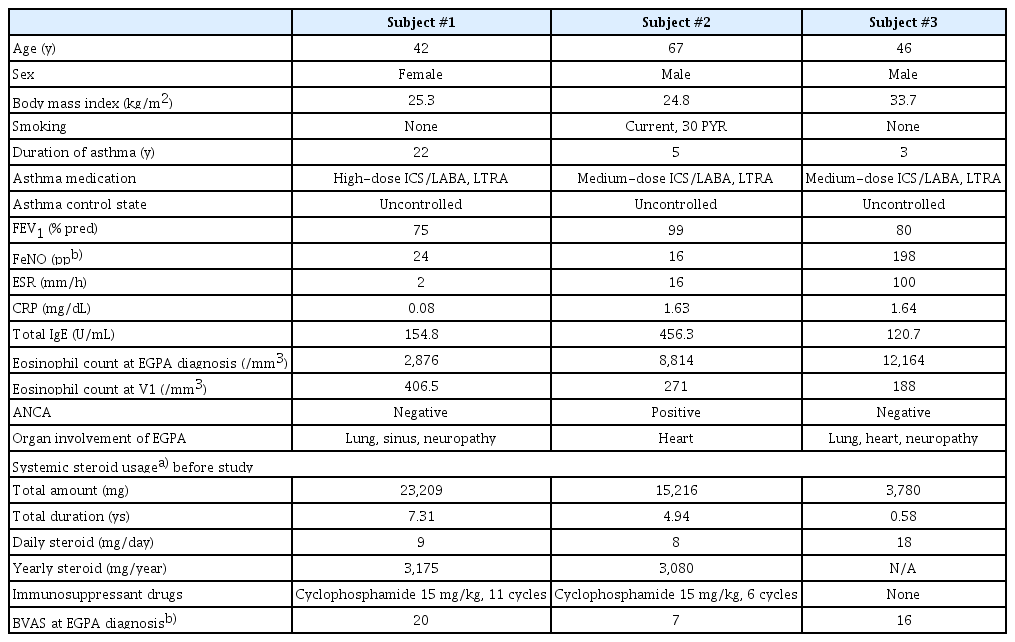

Baseline clinical characteristics of study subjects

This prospective observational cohort study comprised 3 patients: 1 female (Subject #1) and 2 males (Subjects #2 and #3). Their baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. All participants were diagnosed with EGPA based on clinical criteria, without histopathological confirmation, and presented severe symptoms and unfavorable prognostic factors. Subject #1 had been on systemic steroids for more than 7 years for pulmonary infiltrates, neuropathy, and sinonasal abnormalities. Reducing her prednisolone dosage to less than 10 mg led to symptoms of dyspnea and elevated blood eosinophil count, indicating a worsening condition. Subject #2 had been treated with systemic steroids for more than 5.5 years due to cardiomyopathy and experienced exacerbated heart failure with a blood eosinophil count of 3,542/mm3 after stopping prednisolone. Both Subjects #1 and #2 had taken more than 3 g of prednisolone per year for several years and had previously undergone treatment with cyclophosphamide. Subject #3 was treated with systemic steroids, beginning with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (1–2 mg/kg) for 1 week and gradually tapered, due to cardiomyopathy, lung infiltrates, and neuropathy. He was unable to discontinue prednisolone due to his cardiopathy and neuropathy and chose not to receive cyclophosphamide, as he was hesitant to use additional immunosuppressants during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. The patients refrained from using immunosuppressants other than cyclophosphamide due to concerns about the potential adverse events linked to these medications. Additionally, none of the patients received add-on biologics, as they could not afford the associated cost.

Laboratory findings, EGPA symptoms, and BVAS

Blood eosinophil count, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, fractional exhaled nitric oxide, and total IgE level were measured according to the study protocol (Supplementary Table 1). Subject #1’s blood eosinophil count decreased after the first dose of mepolizumab and remained at fewer than 150/mm3 during treatment. However, 3 months after stopping mepolizumab (V13), her count increased, leading to worsening symptoms and an increased need for systemic steroids. Subject #2 also experienced a decrease in eosinophils to fewer than 150/mm3 after the first dose, with counts remaining low during treatment. Although the level increased slightly 6 months after steroid cessation (V14), it remained at fewer than 500/mm3, and his EGPA and asthma symptoms remained stable. Subject #3 experienced a similar decrease in eosinophil count, but his levels at 3 months post-treatment (V13) increased to greater than 500/ mm3. He experienced 2 asthma exacerbations requiring steroid treatment during follow-up.

In addition, EGPA symptoms and the BVAS were evaluated throughout the study (Supplementary Table 2). In Subject #1, neurologic symptoms resolved after 2 doses of mepolizumab, and BVAS decreased during the treatment phase. However, BVAS did not reach 0, and sinonasal symptoms worsened at V13 after cessation of mepolizumab, with new pulmonary symptoms of wheezing and dyspnea. In contrast, Subjects #2 and #3 maintained stable EGPA symptoms and BVAS throughout both treatment and follow-up phases.

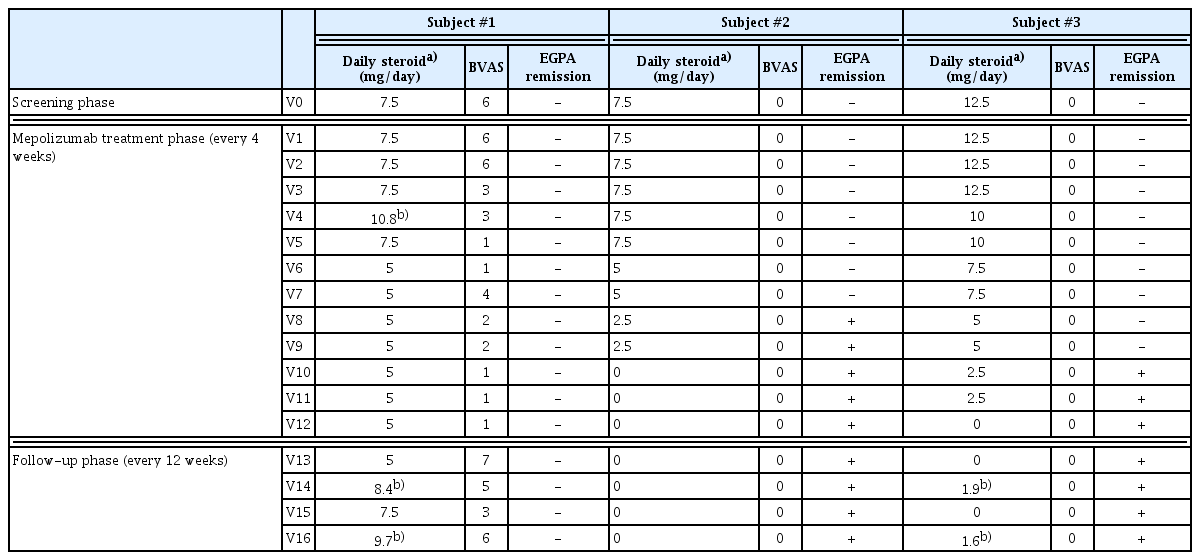

Systemic steroid use and EGPA remission

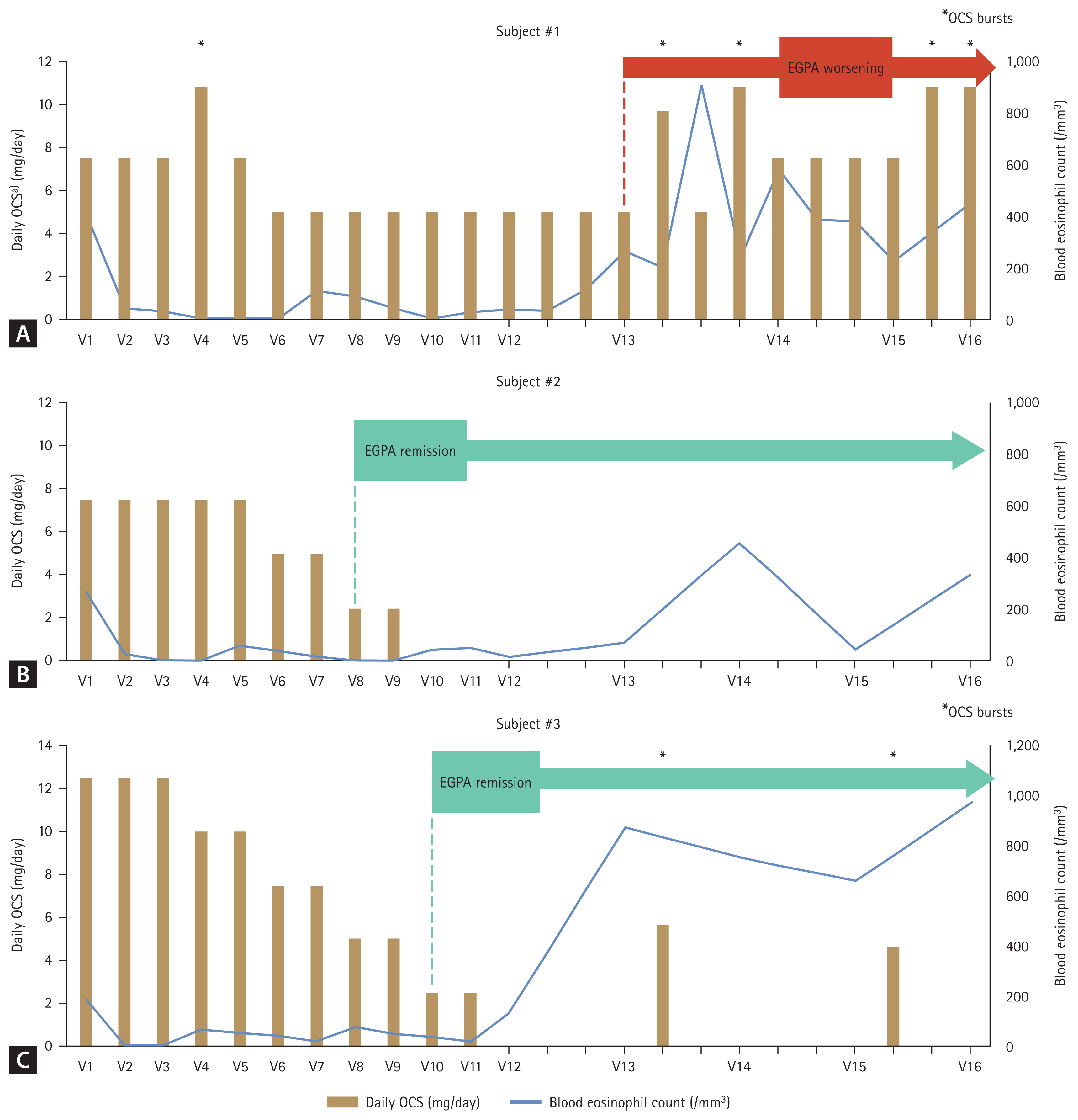

The use of systemic steroids, the BVAS, and the remission state of EGPA are summarized in Table 2. Subjects #2 and #3 successfully reduced their steroid dosage to less than half of the initial after 8 months of mepolizumab treatment (V8) and achieved complete cessation by V10 and V12, respectively, maintaining this for the entire follow-up year. Subject #1 also reduced her steroid dosage but only by 33% during 1 year of mepolizumab treatment. After stopping mepolizumab, her steroid dose needed to be increased again.

Subjects #2 and #3 attained EGPA remission at V8 and V10, respectively, and this remission state persisted throughout the follow-up period. However, Subject #1 did not achieve EGPA remission as her BVAS score remained higher than 0, with a daily steroid maintenance dose exceeding 4 mg/day. Additionally, her BVAS score increased by 6 points at V13 after stopping mepolizumab, and her oral corticosteroid (OCS) dosage increased to nearly 10 mg/ day by the end of the follow-up phase.

Throughout the study, some patients experienced steroid bursts (Supplementary Table 3). Subject #1 experienced 5 steroid bursts, while Subjects #2 and #3 had 0 and 2 bursts, respectively, mainly for asthma exacerbations linked to upper respiratory infections. Although Subject #3 experienced 2 systemic steroid bursts after discontinuing mepolizumab, these were not considered relapses of EGPA, as they were linked to upper respiratory infections. The patient successfully recovered from asthma exacerbations following each steroid burst, maintaining asthma control without worsening symptom scores (Supplementary Table 4) or the need to restart systemic steroid maintenance treatments. Moreover, the mean steroid dose was less than 4 mg/day at V14 and V16 and did not impact the BVAS calculation or the physician’s assessment of EGPA control. On the other hand, Subject #1 developed new respiratory symptoms and worsening sinonasal abnormalities without any acute respiratory infection during the follow-up phase. This led to an increase in her systemic steroid maintenance dose, reflecting worsening EGPA in the BVAS calculation. The deterioration was classified as worsening rather than a relapse since this patient never achieved EGPA remission.

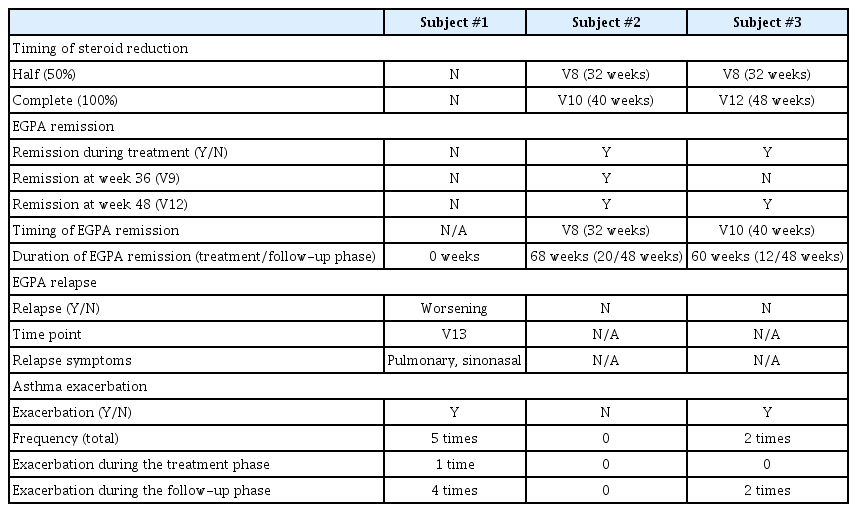

Summary of clinical outcomes

The clinical outcomes for each study subject are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2. In Subject #1, treatment with mepolizumab led to a reduction in daily steroid use and blood eosinophil count. However, after discontinuing mepolizumab, the patient’s symptoms related to EGPA worsened, resulting in several asthma exacerbations and an increase in steroid dosage. In Subject #2, mepolizumab successfully achieved remission of EGPA and achived complete cessation of systemic steroid treatment. Notably, the effects of the treatment persisted for 1 year after mepolizumab was stopped. Subject #3 also attained remission from EGPA and achieved cessation in systemic steroids during mepolizumab treatment, and this improvement was maintained throughout the follow-up period.

Summary of OCS use, blood eosinophil counts, and clinical course in the study subjects (A, Subject #1; B, Subject #2; C, Subject #3). a)Daily OCS is presented as the equivalent prednisolone dose and was calculated by dividing the total amount of systemic steroids used by the follow-up duration at every month. OCS, oral corticosteroid; EGPA, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis; V, visit.

DISCUSSION

This study is a 2-year prospective observational trial serving as the first pilot study of the Korean EGPA cohort. Our findings indicate that low-dose mepolizumab treatment is clinically effective in reducing the maintenance dosage of systemic steroids required by patients with EGPA. Moreover, it is effective for refractory patients exhibiting severe disease features. In some cases, low-dose mepolizumab reduces steroid use and leads to remission of EGPA, allowing cessation of systemic steroids, a benefit that has continued for up to 1 year after discontinuing mepolizumab treatment. These results support the use of low-dose mepolizumab in treating EGPA, even in patients with refractory disease and severe manifestations. This approach is especially helpful for those who cannot afford high-dose mepolizumab or for patients with severe symptoms at risk of side effects from immunosuppressants.

The study also addresses several clinical considerations. First, symptoms of EGPA worsened after discontinuing mepolizumab in a patient who had not achieved remission during treatment. Therefore, low-dose mepolizumab should be continued for patients who do not achieve remission in EGPA. Second, we observed similar changes in blood eosinophil counts in this longitudinal cohort of EGPA patients receiving low-dose mepolizumab treatment. After a single dose of mepolizumab 100 mg, blood eosinophil count dropped to fewer than 150/mm3 in all 3 EGPA patients. However, these levels increased to more than 500/mm3 at 3 to 6 months after stopping mepolizumab, yet the patients did not experience worsening of EGPA symptoms.

In asthma management, recent efforts have focused on OCS stewardship, largely due to the increasing use of biologics. Researchers have raised concerns about the indiscriminate use of OCS, as it can lead to severe side effects and irreversible damage. Cumulative lifetime doses exceeding 1,000 mg of prednisolone equivalents can result in serious adverse effects, including weight gain, osteoporosis, hypertension, glucose intolerance, and increased risk of infections. While the number of patients with EGPA is significantly lower than those with asthma, EGPA patients often require high doses of systemic steroids throughout their lives, as glucocorticoids are the primary treatment targeting eosinophilic inflammation.

When examining the characteristics of patients enrolled in the MIRRA and MANDARA trials, the level of OCS consumption for treating EGPA is concerning. In the MANDARA trial, the median dose of oral glucocorticoids was 10.0 mg/day, with a range of 5.0 to 30.0 mg/day, and an average disease duration of 5.39 ± 5.38 years. In the MIRRA trial, OCS doses were similar, with a median of 12.0 mg/day, ranging from 7.5 to 40.0 mg/day, and an average disease duration of 5.2 ± 4.4 years. A patient taking 10 mg of prednisolone consumes roughly 3,650 mg of OCS in just 1 year, which is significantly higher than the known harmful dosage. Patients in our cohort study also reported consuming more than 3,000 mg annually for several years. However, they struggled to reduce their OCS usage because of exacerbated cardiac, pulmonary, or neuropathic symptoms related to EGPA. As severe symptoms can even be life-threatening, treatment for EGPA should address the various concerns associated with systemic steroid use.

The current definition of remission, characterized by a BVAS of 0 and a systemic steroid dose less than 4 mg/day, warrants critical reconsideration, particularly in the context of OCS stewardship. The ultimate objective in treating EGPA should be complete cessation of maintenance OCS and remission. This is essential because even the so-called acceptable OCS dose of 4 mg per day translates to 1,460 mg annually, which is excessive. Biologic treatments that specifically target IL-5 and eosinophils present a promising opportunity to significantly reduce reliance on systemic steroids without leading to serious side effects, assuming we overcome existing cost barriers. While low-dose mepolizumab is not FDA-approved for EGPA treatment, many patients with this condition also struggle with severe asthma. Thus, prescribing a standard asthma dose of mepolizumab to patients who cannot afford the higher EGPA dosage is justifiable. Our study results support the use of low-dose mepolizumab as a potential means to reduce systemic steroid usage in refractory EGPA patients who exhibit severe features.

Evidence-based guidelines for EGPA recommend the use of mepolizumab for patients with relapsing-refractory EGPA who do not exhibit organ- or life-threatening manifestations. In contrast, rituximab or cyclophosphamide is recommended for treating EGPA with severe symptoms [2]. However, clinicians encounter various challenges in clinical practice when considering the use of these immunosuppressive agents. Both rituximab and cyclophosphamide are associated with a higher risk of adverse events compared to mepolizumab, including secondary infections and chronic organ damage in the kidneys or liver, which can sometimes be fatal. Additionally, there is limited knowledge regarding the outcomes of retreatment with these immunosuppressants in patients who experience multiple relapses of EGPA. Our study suggests that mepolizumab, even at a low dose, may serve as an alternative for EGPA patients with severe features who are intolerant to further immunosuppressive agents or have a previous treatment history with these medications.

In conclusion, low-dose mepolizumab treatment demonstrated clinical efficacy in reducing the maintenance dose of systemic steroids needed for patients with refractory EGPA who exhibited severe features. Although this was a small pilot study, and not all patients achieved remission from EGPA, some did, and their remission status persisted even after discontinuation of mepolizumab. Additionally, we established a foundational framework for a longitudinal EGPA cohort in Korea for the first time and collected blood samples for future investigations. We anticipate developing a larger nationwide longitudinal cohort in Korea and plan to conduct several studies aimed at gaining detailed insights into the pathogenesis, biomarkers, prognosis, and optimal treatments for EGPA and other eosinophil-associated diseases.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Low-dose mepolizumab treatment has been clinically effective in reducing the maintenance dose of systemic steroids in patients with refractory EGPA exhibiting severe symptoms.

2. Some patients achieved remission from EGPA on low-dose mepolizumab, and this remission status persisted for 1 year even after discontinuing the medication.

3. For the first time, a foundational framework for a longitudinal cohort of EGPA in Korea has been established, and serial blood samples have been collected for upcoming investigations.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Mi-Ae Kim: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing, visualization, project administration, funding acquisition; Ji-Hyun Lee: resources, data curation, supervision; Eun-Kyung Kim: resources, data curation, supervision; Jung-Hyun Kim: resources, investigation, project administration, funding acquisition; Jisoo Park: resources, investigation, project administration, funding acquisition; Se Hee Lee: resources, investigation, project administration, funding acquisition; Tae-Bum Kim: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing – review & editing

Conflicts of Interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2021R1G1A1094123) and by a grant of the Korean Health Technology R&D Project through the Korean Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: RS-2024-00403700).