To the Editor,

Polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) is an inflammatory rheumatic disease affecting mainly elderly people. It is characterized by morning stiffness, pain in the shoulder girdle and hip girdle, and elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP); it typically shows dramatic responses to low-dose corticosteroid [1]. In addition to myalgia, inflammation frequently develops in the tendon and bursa around the shoulder joint in PMR [2]. However, the cause of PMR is at present unknown. We report a female patient in whom PMR developed following paraspinal muscle inflammation and sacroiliitis.

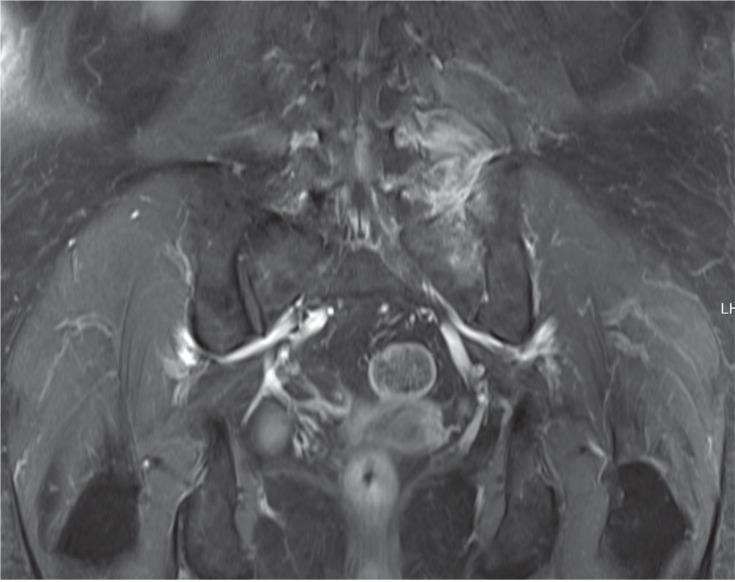

A 68-year-old female presented with pain and stiffness in her low back and left buttock, which had lasted for 4 months. She had been treated with acupuncture and percutaneous nerve block several times but her pain did not improve. On physical examination, she was afebrile and there was tenderness around the left sacroiliac joint and left low paraspinal area. Hand and foot findings were non-specific. On laboratory examination, her white blood cell (WBC) count was 9,980/mm3 (neutrophils 74.6%), hemoglobin (Hb) 10.8 g/dL, platelets 393 ├Ś 109/mm3, ESR 120 mm/hr, and CRP 5.43 mg/dL. Serum alkaline phosphatase, creatine phosphokinase, and thyroid function were within normal limits. Rheumatoid factor was negative, antinuclear antibodies were negative, and HLA-B27 was positive. Blood cultures were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed bone marrow edema of the left transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra, left iliac bone, and left sacroiliac joint as well as edema of the left paraspinal muscle (Fig. 1).

She was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and antibiotics (vancomycin and ceftriaxone) because we could not exclude the possibility of an infection, given that she had been treated with invasive procedures. Two weeks later, her symptoms had improved and ESR decreased to 85 mm/hr and CRP to 3.01 mg/dL. She was discharged with prescriptions for NSAID and oral antibiotics.

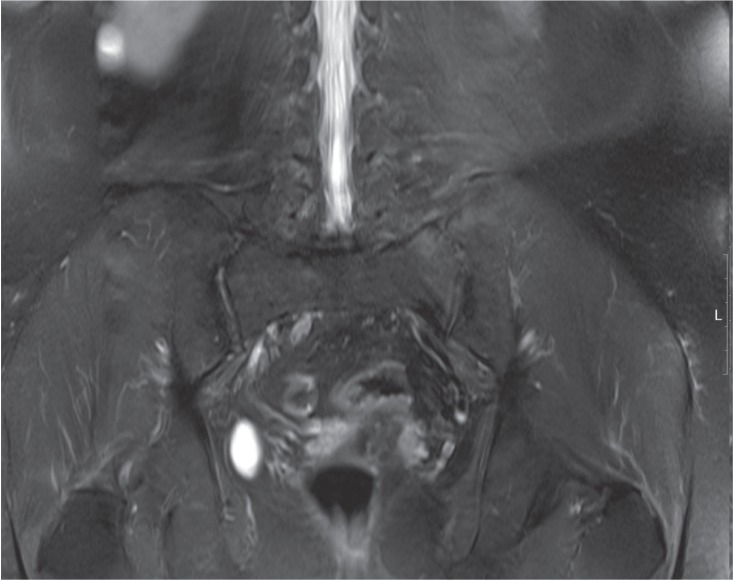

Three weeks after discharge, pain and stiffness in her lower back were aggravated and right shoulder pain developed. On laboratory testing, WBC was 10,510/mm3, Hb 11.0g/dL, and platelets 386 ├Ś 109/mm3. ESR was elevated to 120 mm/hr and CRP to 5.71 mg/dL. However, MRI showed regression of the bone marrow edema of the left fifth lumbar vertebra, iliac bone, and sacroiliac joint, as well as improvement of the left paraspinal muscle inflammation (Fig. 2). Musculoskeletal ultrasound of the right shoulder revealed subacromial bursitis.

Elevation of ESR and CRP, the absence of rheumatoid factor, development of subacromial bursitis, aggravation of lower back stiffness and pain despite improvement of the initial inflammation on MRI, and the absence of other joint involvement suggested the possibility of PMR [2] and we added prednisolone 15 mg. Her pain improved markedly the next day; the pain visual analog scale decreased from 7 to 3. On the 6th day of prednisolone treatment, her back pain was almost relieved and CRP decreased to 1.58 mg/day. Based on the rapid and excellent response to the low-dose glucocorticoid, she was diagnosed with PMR. Then, while tapering the dose of prednisolone, she suffered another episode of disease flare, which responded again to an increased dose of prednisolone. Seven months after the last admission, she has been taking prednisolone 7.5 mg/day with methotrexate 10 mg/week and feeling little pain. In the latest laboratory tests, ESR was 54 mm/hr and the CRP level was 0.26 mg/dL, within normal limits.

PMR is a clinical diagnosis; no specific diagnostic test or pathological finding is known. Diagnosis is usually made based on the clinical presentation and evidence of systemic inflammation in PMR [1]. In our case, myalgia and stiffness were aggravated and inflammatory markers, such as ESR and CRP, increased despite improvement of the initial inflammatory findings on MRI. Subacromial bursitis occurring in the right shoulder and 15 mg of prednisolone inducing a rapid and dramatic response strongly supported the diagnosis of PMR [2].

Several conditions can present with the inflammatory manifestations seen in our patient and spondyloarthritis (SpA) seemed to be the most important, considering that our patient initially presented with inflammation of the sacroiliac joint, elevation of CRP and HLA-B27 positivity, which are all included in the Assessment in Spondyloarthritis International Society classification criteria [3]. SpA that develops after the age of 50 years is termed late-onset SpA. Patients with late-onset SpA frequently present with PMR-like features, such as pain and stiffness in the shoulders and hip girdles, unexplained constitutional symptoms, and high levels of acute phase reactants at the beginning of the disease. There are several case reports of late-onset SpA mimicking PMR [4]. Thus, it is important to make a differential diagnosis between late-onset SpA and PMR. Late-onset SpA is characterized by the presence of inflammatory swelling with pitting edema over the dorsum of the feet, oligoarthritis involving the lower extremities, such as the ankle and knee joints, and minimal involvement of the axial skeleton [4], which was not compatible with our case. Additionally, while the back pain was aggravated after treatment with antibiotics and NSAIDs in our patient, MRI showed marked improvement of the initial inflammatory findings in the sacroiliac joint. Regarding treatment, it has been reported that a response to corticosteroids is absent or partial in SpA and diagnosis of SpA becomes evident during follow-up when subjects fail to respond to steroid therapy and develop the typical manifestations of SpA. Thus, the possibility of late-onset SpA should be considered in PMR patients with poor responses to corticosteroids and multiple flares [4]. However, our patient showed a marked response to the corticosteroid and stayed in good condition with corticosteroid of < 10 mg per day, making the diagnosis of PMR more likely.

In our case, PMR occurred following paraspinal muscle inflammation and sacroiliitis. Considering the sequence of events, we suspect that long-lasting paraspinal muscle inflammation and sacroiliitis might have built up a systemic inflammatory milieu and triggered the PMR. However, it was not clear what caused the initial paraspinal muscle inflammation and sacroiliitis. We first considered the possibility of infection. However, the patient was afebrile, blood cultures were negative, and there was no abscess on MRI, although she had suffered from low back pain and left buttock pain for a prolonged period. These all made it seem less likely that an infection was the initial problem. It was also possible that the initial pain was due to the PMR. However, it is known that typical muscle inflammation is not present on MRI in PMR [1]. In our case, paraspinal muscle inflammation was definite on MRI, suggesting that PMR had not yet developed when the patient was first admitted.

Regarding etiology, the cause of PMR is still unknown. There are several reports about a genetic association involving genes for intercellular adhesion molecule 1, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist, and interleukin 6 [1]. There is no direct evidence for an infectious cause of PMR, although the incidence of PMR was reported to coincide with epidemics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae, parvovirus B19, and Chlamydia pneumoniae infections [1]. There is a report of three patients with PMR who were successfully treated with the antibiotic clarithromycin. However, the authors considered that the effectiveness of clarithromycin in PMR was due to its anti-inflammatory effects, not its antibacterial activity [5]. There are reports that patients with PMR may have disturbances in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis with some adrenal insufficiency, but this remains to be confirmed [1].

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print