Clinical outcome of acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding after hours: the role of urgent endoscopy

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims:

This study was performed to investigate the clinical role of urgent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (ANVUGIB) performed by experienced endoscopists after hours.

Methods:

A retrospective analysis was performed for consecutively collected data of patients with ANVUGIB between January 2009 and December 2010.

Results:

A total of 158 patients visited the emergency unit for ANVUGIB after hours. Among them, 60 underwent urgent EGD (within 8 hours) and 98 underwent early EGD (8 to 24 hours) by experienced endoscopists. The frequencies of hemodynamic instability, fresh blood aspirate on the nasogastric tube, and high-risk endoscopic findings were significantly higher in the urgent EGD group. Primary hemostasis was achieved in all except two patients. There were nine cases of recurrent bleeding, and 30-day mortality occurred in three patients. There were no significant differences between the two groups in primary hemostasis, recurrent bleeding, and 30-day mortality. In a multiple linear regression analysis, urgent EGD significantly reduced the hospital stay compared with early EGD. In patients with a high clinical Rockall score (more than 3), urgent EGD tended to decrease the hospital stay, although this was not statistically significant (7.7 days vs. 12.0 days, p > 0.05).

Conclusions:

Urgent EGD after hours by experienced endoscopists had an excellent endoscopic success rate. However, clinical outcomes were not significantly different between the urgent and early EGD groups.

INTRODUCTION

Acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (ANVUGIB) is a common disorder that warrants hospital admission and emergency management [1,2]. Despite considerable advances in endoscopic hemostasis and pharmacologic treatment, the mortality and morbidity from ANVUGIB are considerably high. The mortality from further bleeding or from decompensation of a concomitant medical condition is known to be about 5% to 10% [1,3-6].

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) plays a key role in both diagnosis and treatment of ANVUGIB [7]. Early EGD performed within 24 hours after presentation to a hospital has become a standard therapeutic approach for ANVUGIB [8,9]. However, in clinical practice, many patients presenting ANVUGIB visit the emergency unit after hours, on a weekend, or on a weekday evening. A clinical assessment is often needed to determine whether or not an immediate EGD after hours (sooner than within 24 hours) should be performed, especially in high-risk patients presenting with massive hematemesis or with signs of hemodynamic instability. The role of urgent EGD (defined as within 2 to 12 hours) has been investigated in many studies [7,10-17], most of which have failed to show an apparent clinical benefit of urgent EGD. However, most of these studies enrolled a considerable portion of low-risk patients and did not clearly describe whether urgent EGD was performed by experienced endoscopists after hours. To date, there are limited data on the clinical role and benefit of urgent EGD in selected high-risk patients when urgent EGD is performed by experienced endoscopists. Showing the benefit of urgent EGD after hours may promote the use of this rapid intervention. Therefore, this study was performed to examine the clinical outcome of ANVUGIB after hours and to investigate the clinical role and benefit of urgent EGD performed by experienced endoscopists in both low-risk and high-risk patients.

METHODS

Patients

From January 2009 to December 2010, patients admitted to the emergency unit in Seoul National University Bundang Hospital for ANVUGIB after hours were considered for inclusion in the current study. All patients were immediately resuscitated with intravenous fluids and blood transfusions and underwent early EGD within 24 hours of admission. “After hours” was defined as weekdays from 6:00 PM to 8:00 AM or weekends from 1:00 PM on Saturday to 8:00 AM on Monday.

The data for enrolled patients were classified into three categories: preprocedural, procedural, and outcome data. Hemodynamic instability was defined as a systolic blood pressure of less than 100 mmHg, with symptoms or signs of organ hypoperfusion. The clinical Rockall score was used for risk stratification [18]. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital.

Endoscopic procedure

In all enrolled patients, EGD was performed within 24 hours after admission. The decision to perform immediate EGD after hours was made with clinical judgment at the emergency unit. Enrolled patients were divided into two groups according to the time from initial admission to EGD, with the urgent EGD group defined as EGD within 8 hours and the early EGD group defined as EGD at 8 to 24 hours. All endoscopic procedures were performed by two experienced endoscopists (SHL and YSP) who had experience in endoscopic examination of more than 6,000 cases and experience in endoscopic hemostasis of more than 500 cases. High-risk findings on EGD were defined as active bleeding, adherent blood clot, or exposed vessels showing on endoscopic examination. In some cases with high-risk endoscopic findings, endoscopic hemostasis using varying methods, such as epinephrine injection, thermal hemostasis, or mechanical hemostasis, was performed based on the endoscopist’s judgement.

Clinical outcome

The primary outcome of the current study was defined as primary hemostasis, recurrent bleeding, and 30-day mortality. The secondary outcome was defined as the number of endoscopic sessions for permanent hemostasis, the need for angiographic embolization or emergent surgery, blood transfusion requirements, length of hospital stay, and bleeding-related mortality.

Failure of primary hemostasis was defined as persistent active bleeding, despite initial endoscopic management or any evidence of active bleeding such as hematemesis, hematochezia, and hemodynamic instability within 12 hours after primary hemostasis [19,20]. Recurrent bleeding was defined as ongoing bleeding, in the form of fresh hematemesis, hematochezia, fresh blood aspirated via a nasogastric tube, instability of vital signs, or a reduction in hemoglobin by more than 2 g/dL 12 hours after primary hemostasis [19,20]. Patients with clinical evidence of recurrent bleeding received a prompt endoscopic examination. In the case of recurrent bleeding not amenable to endoscopic therapy, angiographic embolization or emergent surgery was considered according to the individual clinical situation. After hemostasis was achieved, each patient was followed as an outpatient for at least 2 months to evaluate the long-term outcome. For patients who were not available for clinical evaluation for this period, telephone contact was attempted to obtain information about the clinical outcome.

Statistical analysis

Fisher exact test, Pearson chi-square test, or an unpaired two-tailed test was used, as appropriate, to calculate the statistical significance of differences of baseline characteristics, endoscopic findings, and clinical outcomes. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to identify independent factors affecting clinical outcomes, which included age, sex, and probable predictors affecting the clinical outcomes with p values of < 0.20 in simple linear regression analysis. A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Preprocedural data for enrolled patients

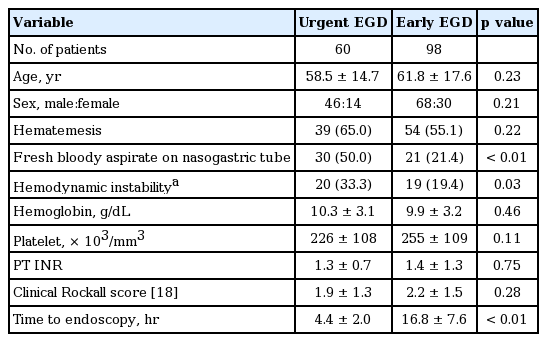

A total of 378 patients were admitted to the emergency unit and underwent EGD for ANVUGIB from January 2009 to December 2010. Among those patients, 158 (42%; 60.5 ± 16.6 years; range, 18 to 101) were admitted to the emergency unit after hours. The presenting manifestation was hematemesis in 73 patients (46.2%), melena in 65 patients (41.1%), and both in 20 patients (12.7%). Shock was observed on initial admission in 39 patients (24.7%), and the mean hemoglobin level on initial admission was 10.0 ± 3.1 g/dL (range, 4.0 to 17.6). The frequency of comorbidities was 34.2% (54 of 158 patients). The comorbidities in both the urgent EGD group and early EGD group included cardiovascular disease, arterial hypertension, chronic renal failure, liver cirrhosis, and malignancy. The mean value of the clinical Rockall score was 2.1 ± 1.4 (range, 0 to 7). The mean time from initial admission to EGD was 12.1 ± 8.6 hours (range, 1 to 24); this was significantly lower in the urgent EGD group compared with the early EGD group (4.4 hours vs. 16.8 hours). There were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to preprocedural data, with the exception of the frequency of hemodynamic instability and fresh bloody aspirate on the nasogastric tube, which were significantly higher in the urgent EGD group (Table 1) [18].

Procedure data for enrolled patients

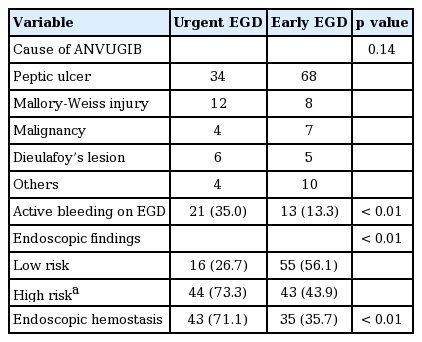

Of a total of 158 patients, 60 underwent urgent EGD and 98 underwent early EGD. A diagnosis was made at initial EGD in all 158 patients. The cause of ANVUGIB was peptic ulcer in 102 patients (64.6%), Dieulafoy’s lesion in 11 patients (7.0%), Mallory-Weiss injury in 20 patients (12.7%), and malignancy in 11 patients (7.0%). Active bleeding (arterial spurting or micropulsatile streaming) was noted at EGD in 34 patients (21.5%), and high-risk findings on EGD were noted in 87 patients (55.8%). The frequencies of active bleeding and high-risk findings on EGD were significantly higher in the urgent EGD group, and endoscopic hemostasis was performed more often in the urgent EGD group (Table 2).

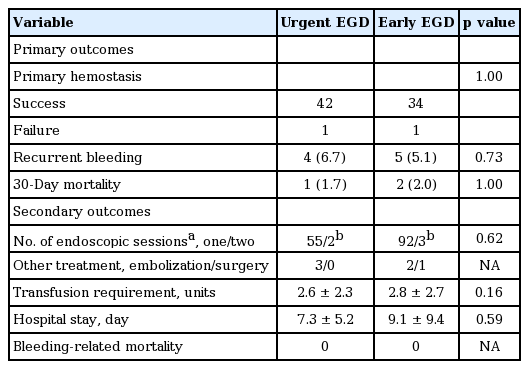

Primary outcome

Outcome data are summarized in Table 3. Primary hemostasis was achieved in all but two patients. In these two patients (one each in the urgent and early EGD groups), massive active bleeding from a duodenal ulcer was noted, and endoscopic hemostasis was not successful. These two patients required angiographic embolization for hemostasis. Recurrent bleeding after primary hemostasis occurred in nine patients (5.7%), four in the urgent EGD group, and five in the early EGD group. Among four patients with recurrent bleeding in the urgent EGD group, two achieved successful secondary hemostasis with endoscopic treatment whereas the other two required angiographic embolization for hemostasis. In the early EGD group, five patients experienced recurrent bleeding. Three patients achieved successful hemostasis with endoscopic treatment whereas the other two required angiographic embolization and surgery for hemostasis, respectively. Thirty-day mortality occurred in three patients, one in the urgent EGD group and two in the early EGD group. These three patients had achieved successful hemostasis with one or two sessions of endoscopic treatment; the causes of mortality in these patients were pneumonia, hepatic failure, and underlying malignancy, respectively. There were no significant differences in primary outcome between the two groups (p > 0.05). During the 2-month follow-up, there was no further recurrence of bleeding in either group.

Secondary outcome

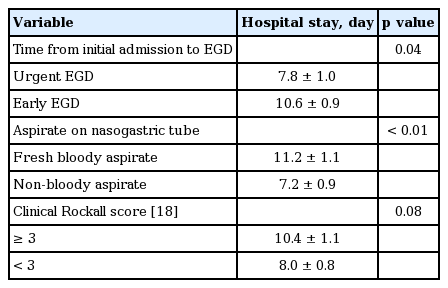

With respect to secondary outcome, endoscopic failure and the subsequent need for other treatments for hemostasis occurred in six patients, three each in the urgent and early EGD groups. The need for multiple endoscopic sessions to achieve permanent hemostasis, the number of blood transfusions, and the length of hospital stay were not significantly different between the two groups (p > 0.05). There was no bleeding-related mortality in the current study (Table 3). In a multiple linear regression analysis, urgent EGD and fresh bloody aspirate on the nasogastric tube were found to be statistically significant factors for a decrease of hospital stay (Table 4) [18].

Outcome in high-risk patients

To find the clinical role and benefit of urgent EGD in high-risk patients, primary and secondary outcomes were investigated in patients with a high clinical Rockall score (≥ 3). The outcome data in this high-risk group are summarized in Table 5. The primary outcome was not significantly different between the two groups. The length of hospital stay tended to be higher in the early EGD group than in the urgent EGD group, although this difference was not significant (p > 0.05). There were no significant differences in other secondary outcomes between the two groups (p > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Currently, guidelines recommend early EGD within 24 hours after admission for ANVUGIB [8,9]. Early EGD within 24 hours is known to decrease the rate of recurrent bleeding, the length of hospital stay, and the need for surgery without any major complications [21-24]. However, in clinical practice, an urgent EGD earlier than within 24 hours is often needed in a certain subgroup of high-risk patients presenting with massive hematemesis or signs of hemodynamic instability. The urgent EGD could be performed without any additional clinical burden or cost if the admission to a hospital for ANVUGIB occurs during working hours. In clinical practice; however, many patients visit the hospital for ANVUGIB after hours, when endoscopic services by experienced endoscopists are not often available in most hospitals. Because the provision of endoscopic services by experienced endoscopists, even after hours, may place a considerable burden on both hospital and society, evidence of clinical benefit of this endoscopic service would be needed. In our institution, all endoscopic procedures for ANVUGIB have been performed by experienced endoscopists even after hours. We performed the current study with the hypothesis based on our clinical experience that urgent EGD may be beneficial in a certain subgroup of sick patients when the endoscopic procedure is performed by experienced endoscopists. In this study, endoscopic hemostasis could be achieved without any additional endoscopic sessions in most cases in the urgent EGD group, even in high-risk patients with massive bleeding. The clinical outcomes in the urgent EGD group, despite a higher rate of high-risk patients, were not inferior to those in the early EGD group. The results of this study show possible benefits of urgent EGD in high-risk patients when the urgent EGD is performed by experienced endoscopists.

The role of urgent EGD (within 2 to 12 hours) has been investigated in many studies [7,10-17]. Two prospective, randomized, controlled studies compared the clinical outcome according to the time to EGD and showed no benefit of urgent EGD. However, these two studies included only hemodynamically stable patients and mainly addressed the issue of decreased length of hospital stay and cost in low-risk patients. Other studies, which were performed with retrospective designs, also failed to show an apparent clinical benefit of urgent EGD [7,12-15]. Most of these studies, however, enrolled a considerable portion of low-risk patients and did not classify patients into working hours and after hours. Furthermore, all of these studies did not clearly describe whether urgent EGD was performed by experienced endoscopists even after hours. We believe that most of the urgent EGD in these studies may have been performed by less experienced endoscopists compared with specialists available during working hours. The current study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to address the role of urgent EGD by experienced endoscopists after hours.

To date, two studies have proven the benefit of urgent EGD. Lin et al. [16] reported that urgent EGD within 12 hours reduced the length of hospital stay and the need for blood transfusion in patients with bloody nasogastric aspirate. In this study, all endoscopic procedures were performed by experienced endoscopists. However, the time of presentation (working hours vs. after hours) was not addressed in this study. Lim et al. [17], in their retrospective study, stratified the very high-risk subgroup in which the Glasgow-Blatchford score is 12 or above, and reported that urgent EGD within 13 hours of presentation was associated with lower mortality in this subgroup. In our study, more than half the patients (82 of 158) were included in the very high-risk subgroup with a Glasgow-Blatchford score ≥ 12. However, 30-day mortality occurred in only two patients in this subgroup (2.4%), and no patient experienced bleeding-related mortality, which could be explained by the fact that all endoscopic procedures, in our study, were performed by experienced endoscopists even in the urgent EGD group.

In this study, the frequencies of high-risk endoscopic findings, such as active bleeding, blood clots, or exposed vessels, were significantly higher in the urgent EGD group; the requirement for endoscopic hemostasis was also higher in the urgent EGD group. This could be explained by the fact that the time between active bleeding and EGD allowed for a previous bleeding lesion to commence healing, which might downstage the lesion from one that requires endoscopic hemostasis to a low-risk lesion that can be managed with pharmacological therapy alone [12,25]. When earlier EGD is performed for ANVUGIB, the higher risk endoscopic findings and greater blood retention may obscure the endoscopic view and make the performance of endoscopic hemostasis difficult or impossible [7,12]. Furthermore, several studies have shown that repeated EGD is required in 5% to 12% of peptic ulcer bleeding cases [26-28]. However, in this study, all except one patient achieved primary hemostasis in the urgent EGD group. Diagnostic failure at the first endoscopy due to an obscured endoscopic view did not occur in any patients, and the need for multiple endoscopic sessions to achieve permanent hemostasis was rare (2 of 57 patients, 3.5%) and not higher in the urgent EGD group, compared with the early EGD group. The results of this study show that technical problems matter little even in high-risk patients with massive bleeding when urgent EGD is performed by experienced endoscopists.

In this study, the length of hospital stay tended to be lower in the urgent EGD group than in the early EGD group, which is somewhat surprising considering that the degree and severity of comorbidities, as reflected in the clinical Rockall score, were not significantly different between the two groups. A possible explanation for this finding is that earlier endoscopic hemostasis can achieve more prompt correction of hemodynamic instability, which may prevent deterioration of underlying comorbidities.

Our study has several limitations. First, because this study was performed with a retrospective design, the selection bias between the two groups may have influenced the clinical outcome. In this study, the frequencies of hemodynamic instability and fresh blood aspirate on the nasogastric tube were significantly higher in the urgent EGD group. Although we investigated the clinical outcome separately only in high-risk patients with a high clinical Rockall score [18], there may still be unmeasured or intangible factors associated with adverse outcomes that are more prevalent in the urgent EGD group, which could adversely influence the clinical outcome in that group. However, despite this adverse effect, the clinical outcome of the urgent EGD group was not inferior to that of the early EGD group. Second, this study failed to show the benefit of urgent EGD on primary outcomes. Because primary hemostasis was achieved in nearly all patients, and recurrent bleeding and 30-day mortality were rare in this study, which could be explained by the performance of EGD by experienced endoscopists, the differences of these primary outcomes between the two groups could not be detected. Third, although the length of hospital stay tended to be higher in the early EGD group in high-risk patients, this difference failed to reach statistical significance. This may be caused by an insufficient number of high-risk patients. However, in the early EGD group, the length of hospital stay tended to increase in high-risk patients, whereas it was nearly the same according to risk stratification (low risk vs. high risk) in the urgent EGD group. Furthermore, multiple linear regression analysis showed that urgent EGD was a statistically significant factor for a decrease in hospital stay. Fourth, the role of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) was not addressed in this study. Pre-endoscopy PPI is recommended where early EGD is not available within 24 hours [9]; also, whether or not PPI therapy is administered before EGD may influence the clinical outcome. However, in this study, all except two patients (one each in the urgent and early EGD groups) received PPI therapy before EGD. Therefore, PPI should have little effect on a comparison of the clinical outcomes between the two groups. Finally, to confirm the benefit of urgent EGD by experienced endoscopists even after hours, analysis comparing clinical outcomes after hours between experienced endoscopists and non-experienced endoscopists would be required. However, such analysis could not be performed, because all endoscopic procedures for ANVUGIB were performed by experienced endoscopists, even after hours, in our institution. Further studies with this analysis and cost-effective analysis would be needed to generalize conclusions regarding the benefits of urgent EGD.

In summary, clinical outcomes including both primary and secondary outcomes were not different between urgent and early EGD groups. However, the urgent EGD group, despite a higher rate of high-risk patients showed an excellent endoscopic success rate; clinical outcome was not inferior to the early EGD group. Urgent EGD after hours, if performed by experienced endoscopists, may have possible benefits in a certain subgroup of patients with high-risk signs, such as those with a high clinical Rockall score.

KEY MESSAGE

1. The clinical outcome of urgent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding is favorable when the urgent EGD is performed by experienced endoscopists.

2. The clinical outcomes were not significantly different between urgent and early EGD groups. The clinical outcomes in the urgent EGD group, despite a higher rate of high-risk patients, were not inferior to those in the early EGD group.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.