Treatment of connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: the pulmonologist’s point of view

Article information

Abstract

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) occurs in 15% of patients with collagen vascular disease (CVD), referred to as connective tissue disease (CTD). Despite advances in management strategies, ILD continues to be a significant cause of mortality in patients with CVD-associated ILD (CTD-ILD). There is a lack of randomized, clinical trials assessing pharmacological agents for CTD-ILD, except in cases of ILD-associated systemic sclerosis (SSc). This may be due to the lack of CTD cases available, the difficulty of histological confirmation of ILD, and the various types of CTD and ILD. As a result, evidence-based pharmacological treatment of CTD-ILD is not yet well established. CTD-ILD presents with varying degrees of histology, from inflammation to fibrosis, and a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, from minimal symptoms to respiratory failure. This renders it difficult for clinicians to make decisions regarding treatment options, observational strategies, optimal timing for interventions, and the appropriateness of pharmacological agents for treatment. There is no specific treatment for reversing fibrosis-like idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in a clinical setting. This review describes pharmacological interventions for SSc-ILD described in randomized control trials, and presents an overview of recent advances of CTD-ILD-dependent treatments based on the types of CTD.

INTRODUCTION

Connective tissue disease (CTD) refers to disorders characterized by autoimmune-mediated damage associated with circulating auto-antibodies [1,2] that target various body organs and cause symptomatic presentation. Diagnosis and treatment of CTD has been the focus of a significant amount of research. Pathological mechanisms associated with interstitial changes in lung connective tissue show similar histological, radiological, and clinical characteristics as idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. The overall incidence of CTD-associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) is 15% [3]. Treatments for CTD-ILD are similar to treatments for CTD [4], although there is no clear protocol in cases where the patient is not responsive to first-line CTD treatments. Additionally, treatment can be difficult if the etiology is unclear, and it is not always evident when a change in the current treatment may be required.

There are several issues associated with the management of CTD-ILD. Evidence-based pharmacological treatments for CTD-ILD are not readily available, with the exception of ILD-associated systemic sclerosis (SSc). ILDs show a wide spectrum of histological manifestations [1,5], ranging from fibrosis to inflammation, complicating the process of diagnosis and treatment. Optimal timing of treatment intervention has not been established. Finally, biomarker levels and the severity of extrathoracic and intrathoracic activity can be inconsistent.

Due to the lack of large population studies and proven therapeutic drugs for CTD-ILD, there is no global guideline for treatment. This paper reviews the current approaches used in the treatment of CTD-ILD based on the type of CTD.

DEFINITION OF CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISEASE-ASSOCIATED INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE

CTD can affect the chest wall, pleura, vasculature, airways, and parenchyma [6]. ILD is one of the most common and clinically significant manifestations of CTD [7]. A large percentage of patients with CTD-ILD have a typically progressive and irreversible course that is characterized by inflammation or fibrosis of the lung parenchyma [6].

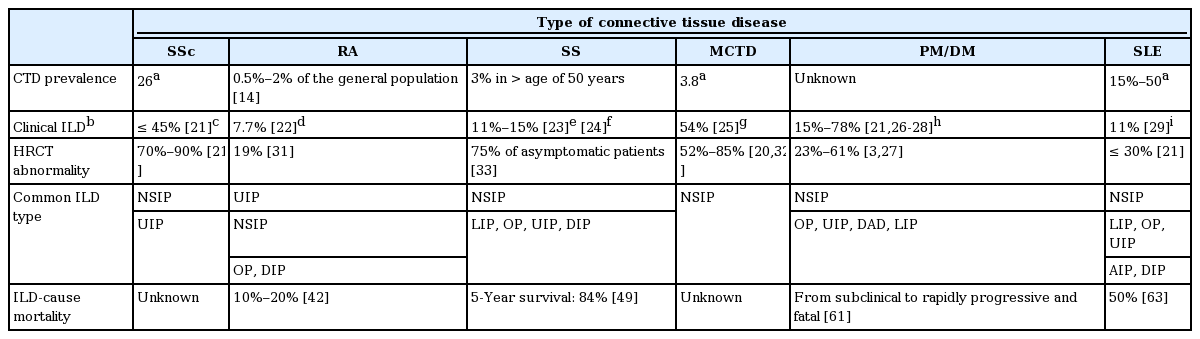

A definitive diagnosis of CTD-ILD is difficult due to variations in pathological presentation and clinical findings (Table 1). CTD-ILD is defined as ILD within the setting of well-defined CTD [8,9], which involves cases of CTD that affect the lung parenchyma and present with respiratory symptoms. In addition to the possibility of being diagnosed with another presentation, new-onset ILD has no identifiable underlying cause and is regarded as idiopathic, although, in the process of differentiating the cause, the etiology of ILD is assumed to be an autoimmune process [10]. The current definition fails to satisfy the rheumatological criteria for a definitive diagnosis of CTD [11], and fails to affirm the findings of serological tests. CTD-ILD is also known by the term “interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF)” [12]. It is difficult to provide a differential diagnosis of CTD-ILD with regard to drug toxicity and infection. A combination of careful physical examination and clinical expertise is required of the physician to accurately determine the CTD-ILD status of a patient.

PREVALENCE OF CTD AND CTD-ILD

The incidence of ILD from CTD increased from 4.46 per 100,000 person-years in 1995 to 2000 to 12.32 per 100,000 person-years in 2001 to 2005 [13]. ILD can be identified in all types of CTD and is particularly common in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), SSc, and polymyositis and dermatomyositis (PM/DM) [1]. Although the prevalence of all CTDs is not well known, RA is the most common CTD, affecting 0.5% to 2% of the general population in the USA (Table 1) [14]. The prevalence of RA in Korea was 0.27 % in 2008. The incidence of RA in 2008 was estimated at 42 per 100,000 in the general population of South Korea [15]. The prevalence of SSc is 26 per 100,000 people in the USA [16]. Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) has a prevalence of about 3% in people over the age of 50 years [17].

The prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in the USA is estimated at 15 to 50 per 100,000 persons [18]. According to the Korean nationwide data, the prevalence of SLE in Korea is 18.8 to 21.7 per 100,000 people [19]. The prevalence of mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD) was 3.8 per 100,000 adults in Norway [20]. PM and DM are very rare [18].

The overall incidence of CTD-ILD is estimated at 15% (Table 1) [3,21-29]. Results of a previous study indicated that the radiographic prevalence rate of subclinical ILD was 33% to 57% in CTD patients [30]. Radiologic prevalence on high-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) was 19% in RA [31], 23% to 38% in PM/DM [3], 30% in SLE [21], 52% to 85% in MCTD [20,32], 75% in SS [33], and 70% to 90% in SSc [21].

EVIDENCE FOR TREATMENT EFFICACY

Treatment decisions should be determined by comparing the reversible treatment effects with the adverse drug reactions. Sufficient evidence exists only for the efficacy of cyclophosphamide (CYC), azathioprine, or rituximab in ILD patients with SSc (SSc-ILD).

Systemic sclerosis

CYC is the only immunosuppressant drug that has been studied in a randomized, controlled trial in CTD-ILD patients. In the Scleroderma Lung Study I, oral CYC at a dosage of 2 mg/kg/day was administered for 1 year to patients, and resulted in significant improvements to forced vital capacity (FVC; 2.53%, p = 0.03). No significant differences in serious adverse events were reported compared to the placebo group [34].

A randomized, controlled trial in Belgium compared oral CYC (2 mg/kg daily for 12 months followed by 1 mg/kg daily) against oral azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg daily for 12 months and then maintained on 2 mg/kg daily). After 12 months of treatment, FVC and diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco) did not change in the CYC group, but showed a statistically significant worsening effect in the azathioprine group [35].

In the Scleroderma Lung Study II, SSc patients with symptomatic ILD were randomized to the oral CYC group (2 mg/kg/day for 1 year followed by placebo) or the mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) group (up to 3,000 mg for 2 years) to assess its efficacy and safety. The FVC, transition dyspnea index (TDI), and modified Rodnan skin thickness scoring (MRSS) improved in both groups. FVC improvement was comparable in the two treatment groups, but there was a greater trend towards improvement of TDI and MRSS in the CYC group compared with the MMF group. The MMF group recorded fewer adverse events such as leukopenia, thrombocytopenia or incidences of weight loss [36].

Adding rituximab to standard medication may improve FVC in SSc-ILD. According to a small, randomized trial (n = 14) [37], there was a significant improvement in FVC in the rituximab group compared with the control group after 1 year (p = 0.0018).

Low-dose corticosteroids and CYC (600 mg/m2) followed by maintenance with azathioprine did not show a significant improvement in FVC when compared against the placebo [38].

We recommend oral CYC at a dosage of 2 mg/kg/day for 1 year, or MMF up to 1,500 mg twice daily for 2 years, as the first-line treatment for SSc-ILD. Adding rituximab to previous immunosuppressant drugs may be an effective therapy for SSc-ILD patients.

Rheumatoid arthritis

Patients with RA can be treated with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) in addition to other medications [39]. In DMARD-naive RA patients, DMARD monotherapy is recommended. Methotrexate (MTX) is the preferred treatment, but sulfasalazine, hydroxychloroquine, or leflunomide may also be recommended. If disease activity remains moderate or high despite the use of DMARD, the American College of Rheumatology guidelines recommend either a combination of traditional DMARD usage, or the addition of a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor as an adjunct therapy [40].

RA-ILD patients lack specific adjunctive treatment options in addition to their traditional treatments. Although a high dose of prednisone has been used as a first-line treatment option in patients with RA-ILD [41], there is insufficient evidence to support its efficacy and safety [42]. Moreover, clinicians may hesitate to commence treatment in RA-ILD patients because DMARD and newer biologic agents may exacerbate ILD and induce opportunistic infection.

Rituximab is effective and tolerated when added to MTX therapy in patients with active RA [43]. Large, randomized, controlled trials evaluating the safety of rituximab in RA-ILD patients are limited. An open label pilot study with RA-ILD patients showed that FVC remained stable in most patients treated with rituximab in combination with MTX at week 48 [44]. However, the study had a very small cohort of patients.

MMF may stabilize or slightly improve lung volumes in patients with RA-ILD [45]. Although MMF is safe and allows for a reduction in prednisone dosage, there is insufficient evidence to support treatment of RA-ILD with MMF owing to the small scale of the prospective cohort study. The stabilizing effects of MMF may be maintained over a median of 2.5 years of follow-up [46].

Sjögren’s syndrome

The majority of SS-ILD patients receive glucocorticoid therapy, antimalarials or immunosuppressive treatment [47]. Corticosteroids administered with hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine or CYC resulted in improved FVC and DLco in SS-ILD patients with histologically proven nonspecific interstitial pneumonia [48,49]. Patients treated with azathioprine or azathioprine-prednisone also show a significant improvement in FVC after at least 6 months of treatment compared with non-treated patients [50].

There are numerous effects of rituximab on serum B cell biomarker changes in patients with systemic complications of SS. However, there are few studies assessing the effects of rituximab on lung function in SS-ILD [51-53].

Mixed connective tissue disease

Most patients diagnosed with MCTD were extremely responsive to corticosteroid therapy. Some patients who were non-responsive (“non-responders”) may progress to a stage of severe organ involvement [54]. Conventional therapies for MCTD-ILD include a combination of corticosteroids with steroid-sparing agents [1]. Corticosteroids, CYC, hydroxychloroquine, MTX and different types of vasodilators have also been used [55].

Polymyositis and dermatomyositis

A monthly intravenous pulse of CYC improved symptoms, vital capacity, and HRCT in progressive interstitial pneumonia in PM/DM in an open-label study [56]. Azathioprine and MMF were also associated with the stabilization of pulmonary physiology, improved dyspnea, and a reduction in steroid dosage. There were no significant differences in these outcomes among the patients who received CYC, azathioprine, and MMF treatments [57].

A systematic review of CYC usage in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) and IIM-ILD showed improvements in vital capacity or FVC (42/59) and HRCT findings (40/52) for the majority of patients [58].

In contrast, non-responders reported a worsening of their condition despite treatment with a high dose of prednisolone in combination with CYC pulses, cyclosporin A, or azathioprine as an adjunct therapy [59,60]. Even early recognition of acute interstitial pneumonia followed by an immediate course of intensified immunosuppressants had limited efficacy [61].

Systemic lupus erythematosus

The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine as the first-line treatment option in patients with SLE [62]. If indicated, initial non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and/or glucocorticoids are recommended. Immunosuppressive agents are used in the treatment of severe refractory cases [63].

The treatment for SLE-ILD typically includes corticosteroids along with steroid-sparing agents. The chosen treatment strategy is based on expert opinion. Highdose corticosteroids and a steroid-sparing agent, often CYC, are initial treatment options for severe SLE-ILD. Corticosteroids with either azathioprine or MMF have been used for mild to moderate cases [64]. Systemic corticosteroids may stabilize inspiratory vital capacity and DLco in the majority of patients with SLE-ILD, although evidence for its efficacy is limited [65].

OPTIMAL TIMING FOR TREATMENT

Indications for treatment with CTD-ILD patients

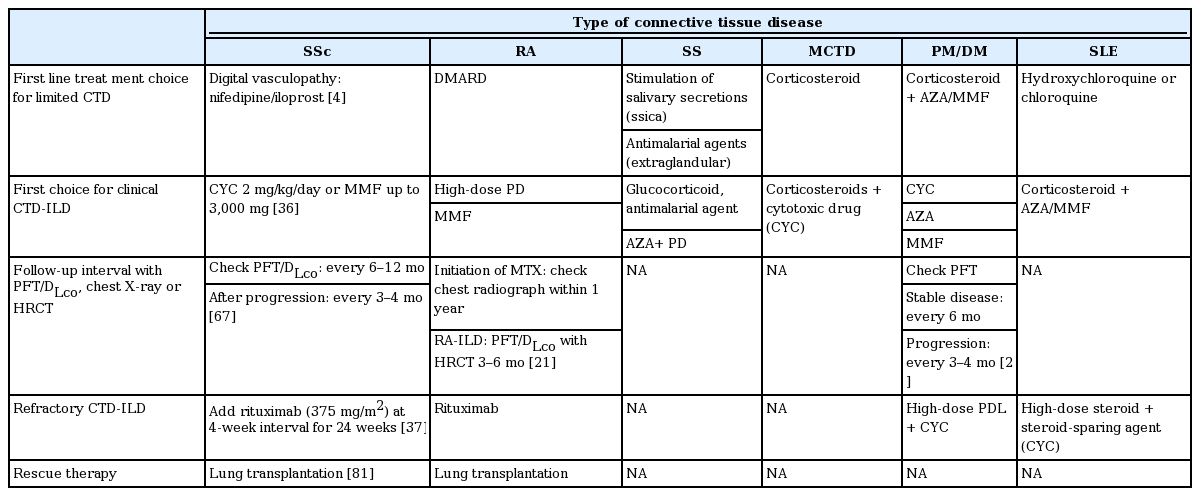

Although there is no consensus for the optimal timing and duration of treatment for CTD-ILD, clinically significant (severe, extensive, or progressive) CTD-ILD is commonly treated with immunomodulatory agents (Table 2) [66].

What is the ‘optimal’ timing for treatment in patients with SSc-ILD?

Patients with CTD may experience involvement of the lung parenchyma. Early detection of CTD-ILD is possible through close monitoring for the detection of newly formed lesions on HRCT and a decline in pulmonary function. Serial evaluation by history taking, physical examination, chest X-ray, pulmonary function test, and HRCT are helpful in the early recognition of CTD-ILD, allowing for an adaptive change in medications upon progression (Table 2) [21,67].

Is it beneficial to start treatment ‘early’?

A higher disease extent (reticular changes in HRCT > 20%) or lower FVC (FVC < 70%) are considered risk factors predisposing patients to poor survival outcomes [68]. An analysis of the Scleroderma Lung Study data [69] showed that patients with less severe baseline HRCT findings may have relatively stable lung function over time, and treatment with CYC does little to improve FVC changes in those patients. Severe HRCT findings are an independent predictive factor of responsiveness to CYC. In patients with an HRCT disease extent of > 50%, the average CYC treatment effect was a 9.81% difference in FVC at 18 months compared to the placebo group (p < 0.001) [69]. Therefore, patients with severe baseline HRCT findings may be responsive to CYC treatment. Optimal timing to commence treatment in patients with SSc-ILD is recommended at an HRCT disease extent of > 20% or a FVC below 70%. The expected therapeutic yield should be greater than the risk of adverse effects associated with immunosuppression, such as opportunistic infections and drug toxicities.

PROMISING TREATMENTS FOR CTD-ILD

Calcineurin inhibitors in DM/PM-ILD: tacrolimus

A retrospective study in Japanese patients with PM/DM-ILD showed significant improvements in eventfree survival in patients who received the conventional therapy of prednisone with intravenous CYC or cyclosporin and tacrolimus compared to those who received conventional therapy alone [70].

Imatinib in SSc-ILD

Open-label pilot studies in SSc-ILD patients demonstrate stabilization of lung function. However, the use of imatinib is associated with high rates of patient withdrawal due to the severity of adverse complications, which include gastrointestinal distress, rash, and renal dysfunction. As many as 40% of enrolled patients withdrew in one study investigating the use of imatinib at a dose of up to 600 mg/day in 20 patients with scleroderma-ILD [71,72].

Target tumor necrosis factor: infliximab and etanercept

Infliximab and etanercept are often regarded as suitable options for patients with RA-ILD. However, patients with RA-ILD may develop new ILD associated with the use of etanercept [73]. Between 1990 and 2010, there were 122 reported cases of new-onset or exacerbated ILD that developed as a secondary event to the administration of biologic therapies (etanercept in 58 cases and infliximab in 56 cases) [74]. These agents should be used with caution in patients with CTD-ILD [7,75].

Targeting antigen-presenting cells: abatacept

A case series with abatacept in patients who developed ILD or whose ILD deteriorated while on anti-TNF-α therapy had no reports of exacerbation or new-onset ILD following administration of abatacept [76].

Targeting interleukin 6 receptor: tocilizumab

Other biologic agents inhibiting the interleukin 6 receptor, such as tocilizumab, may have a role in the future treatment of CTD-ILD. A case report in which tocilizumab was used for an RA patient with a history of MTX-associated pneumonitis, with previous MTX and leflunomide treatment, showed an improvement in the disease activity score and pulmonary functions following tocilizumab treatment [77].

Pirfenidone, nintedanib

Improvements in the vital capacity of patients with scleroderma-ILD following pirfenidone usage have been reported [78]. An open label, randomized, parallel group study for the safety and tolerability of pirfenidone in scleroderma-ILD has been completed recently and similar studies are planned for nintedanib for CTD-ILD patients [7]. We expect that these drugs will have a similar function in CTD-ILD patients to that they would in in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Immunoglobulins

Myositis associated with SSc with early-stage ILD has been treated with intravenous immunoglobulins (2 g/kg/month) and azathioprine (150 mg/day). Ground glass opacities, septal thickenings, and lung function improved following treatment [79].

Stem cell transplantation

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) has been studied in patients with severe refractory scleroderma [80]. An open label parallel group study comparing the safety and efficacy of HSCT treatment and an intravenous pulse of CYC for 12 months showed that HSCT was associated with an increased treatment-related mortality (eight treatment-related deaths) following treatment in 156 patients with early diffuse scleroderma. However, patients undergoing HSCT showed a significant improvement in FVC and total lung capacity. HSCT treatment in scleroderma shows promise with respect to long term survival benefits in patients with SSc-ILD [81].

Lung transplantation

Lung transplantation is considered the final option in the management of CTD-ILD [82]. Between 1995 and 2010, fewer than 2% of all lung transplants worldwide were given to patients with CTD-ILD [83]. According to a Nationwide Cohort Study in the United States [84], SSc patients are considered to be an at-risk group with a high 1-year postoperative mortality rate. This risk is similar to that observed in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH): the mortality rates are 21.37, 19.04, and 17.82 per 100 person-years for SSc, PAH, and ILD patients, respectively. Therefore, SSc-ILD may be considered an acceptable indication for lung transplantation.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY DISCUSSION

Even in cases of well-defined CTD, it is difficult to assess disease progression and how this may impact the tailoring of treatment options. It is important to delineate between the progression of CTD-ILD and other health effects such as respiratory infection, hypersensitivity, drug-associated pneumonitis, environmental exposure, malignancy, or aspiration-induced lung injury [85].

If a definitive diagnosis is not determined in the initial clinical assessment, patients may be diagnosed with unclassifiable ILD (U-ILD). Subsequently, the patients are assessed by a rheumatologist and are classified among the three series of U-ILD: undifferentiated connective tissue disease, IPAF, and U-ILD [8].

Treatment and management options available for CTD-ILD can be improved using a multidisciplinary approach that includes rheumatological collaboration. Multidisciplinary teams should consider intrathoracic and extrathoracic disease activity. Similar to the approach taken with the diagnosis of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia [86], a clinical-radiological-pathological team approach can be used to improve the decision-making processes involved in CTD-ILD [8,12,87].

CONCLUSIONS

CTD-ILD is typically defined as a progressive lung parenchymal manifestation of CTD. Although there is no consensus regarding the optimal timing and duration for treatment of CTD-ILD, clinically severe, extensive, or progressive CTD-ILD is commonly treated with immunomodulatory agents. Multidisciplinary approaches that involve pulmonologists, rheumatologists, radiologists, and pathologists in treatment decisions are necessary for optimal outcomes.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.