Chronic cough, not asthma, is associated with depression in the elderly: a community-based population analysis in South Korea

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Depression and allergic diseases, including asthma, are frequently reported as comorbid conditions. However, their associations have been rarely examined in community-based elderly populations.

Methods

The analyses were performed using the baseline data set of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Health and Aging, which consists of 1,000 elderly participants (aged > 65 years) randomly recruited from an urban community. Depression was assessed using the Geriatric Depression Scale, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Major and minor depressive disorders were diagnosed by psychiatrists. Allergic conditions were assessed using structured questionnaires, lung function, and skin prick test. Quality of life and comorbidities were assessed using structured questionnaires.

Results

Prevalence of asthma and major depressive disorder were 5.4% and 5.3%, respectively. The rate of depression was not significantly different between the non-asthmatic and asthmatic groups. No correlation was observed between the scores obtained using the depression scales and self-reported asthma. However, chronic, frequent, and nocturnal cough were significantly associated with depression and scores obtained using the depression scales, which remained significant in multivariate logistic regression analyses (chronic cough: odds ratio [OR], 3.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.57 to 12.74; p = 0.04). Rhinitis was independently associated with high Mini-Mental State Examination scores (OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.17; p < 0.001) and low 36-item short-form (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.80 to 0.98; p = 0.002).

Conclusions

Depression may not be significantly associated with asthma and allergic diseases in elderly populations, but cough is a significant factor affecting depression.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a global health problem that is relatively common in aging populations. It is projected that the global population of elderly individuals (aged > 65 years) will double in the next 20 years [1]. The prevalence rate of asthma in the elderly population is higher than the previously estimated value (range, 4.5% to 12.7%), and the morbidity and mortality in elderly individuals are more significant than those in younger patients [2,3].

Depression and asthma, which are the fourth and seventh major causes of death in Korea [4], respectively, are associated with aging and these conditions cause high socioeconomic costs [2,5]. Although the causal relationship between asthma and depression has not been fully investigated, previous studies have reported that depression affects healthcare use, adherence to medications, asthma exacerbations, and the quality of life of individuals with asthma [6-9]. To elucidate the association between asthma and depression, several epidemiological studies have been performed; however, the causal direction of these relationships remains controversial. Several studies have reported that asthma is associated with an increased rate of depression [10-13]. On the contrary, these relationships have not been confirmed by other studies [14-16]. These contradictory results may be attributed to the epidemiological and methodological differences between the studies, particularly with regard to comorbid conditions, age of the participants, and assessment tools. Although asthma and depression are prevalent in individuals with advancing age, only few studies have shown the relationship between asthma and depression in the elderly population [13,17-19]. However, in these studies, there were limitations due to the study design or the use of a self-reported questionnaire for the assessment of depression status.

The Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA) is a prospective cohort study of elderly individuals (≥ 65 years old) that investigates the interaction of multimorbidities using a multidisciplinary approach [20]. In a previous study, we examined the epidemiology of cough and found that cough is detrimental to the quality of life in elderly populations [21]. However, studies on the relationship between depression and allergic diseases, such as asthma and rhinitis, in a community-based elderly population are limited. In the present study, we examined the baseline cross-sectional data obtained from KLoSHA database, which used several tools that examine mental health status, including a structured psychiatric assessment tool by neuropsychiatrists. Our study aimed to investigate the association between asthma and depression in a randomly selected, community-based elderly population.

METHODS

Study participants

Data for the analyses were collected via a cross-sectional study that utilized data from the KLoSHA database, and the study was conducted from September 2005 to September 2006 in Seongnam city, Gyeonggi Province [20]. Seongnam is the third largest satellite city of Seoul, and it had a total population of 931,019 in 2005. In total, 1,118 participants were selected from a roster of 61,730 individuals aged 65 years or older who were residents of Seongnam on August 1, 2005. They were fully informed of the study’s purpose, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-1111/140-401).

Assessment of asthma, rhinitis, cough symptoms, and lung function

Asthma was defined by positive responses to both of the following questions: “Have you ever had been diagnosed with asthma? (ever asthma)” and “Have you had a wheezing or whistling in the chest during the last 12 months? (current wheeze),” as previously described [22]. Rhinitis was assessed using questions from a modified questionnaire [23]: “Have you had sneezing or a runny or blocked nose without a cold in the past 12 months?” We evaluated specific rhinitis symptoms using questionnaires on the presence of sneezing, rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, or nasal itching. Frequent cough was defined using the questions “Do you usually cough as much as four to six times a day, 4 or more days a week?” Moreover, chronic cough was defined by a positive answer to the subsequent question “Do you usually cough like this on most days for 3 consecutive months or more during the year?” Nocturnal cough was assessed by asking the question “Have you been awakened by an attack of coughing at any time in the last 12 months?” Spirometry was conducted by an experienced technician using a portable spirometer (Vmax-2130, SensorMedics Corporation, Yorba Linda, CA, USA).

Assessment of mental health status and quality of life

Standardized clinical interviews were conducted by four neuropsychiatrists to diagnose comorbid neuropsychiatric disorders. The research neuropsychiatrists conducted the assessment with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview and the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) [24]. In addition, the Korean version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) [25] and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [26] were utilized. The final diagnosis of each participant was made by a panel of four psychiatrists for major depressive disorder (MDD) and minor depressive disorder (MnDD) according to the guidelines of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). Global cognitive function was assessed using the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-KC) of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) assessment battery [27]. The general quality of life was assessed using the 36-item short-form (SF-36) questionnaire [28]. The SF-36 scale includes eight domains: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health. Patients with a history of cerebrovascular disorders, such as stroke and transient ischemic attack (10.1%, n = 95), were excluded in the analysis of depression.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis used Student’s t test for parametric data. Categorical data were evaluated using the chisquare test. Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the associations between asthma/rhinitis and comorbidities. In the multivariate logistic regression tests for the associations between asthma and rhinitis (with asthma as a dependent variable), confounders included demographic factors (age, sex, body mass index, education years, social support, and income level). To assess the relationship between allergic airway diseases (asthma, chronic cough, rhinitis, and fixed airway obstruction) and psychologic scores, the Student’s t test and Mann-Whitney U test were utilized. The receiver operating curve was used to evaluate the accuracies of the depression scales in allergic diseases. All statistical tests were performed using the SPSS software version 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). All statistical tests were two sided, and p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

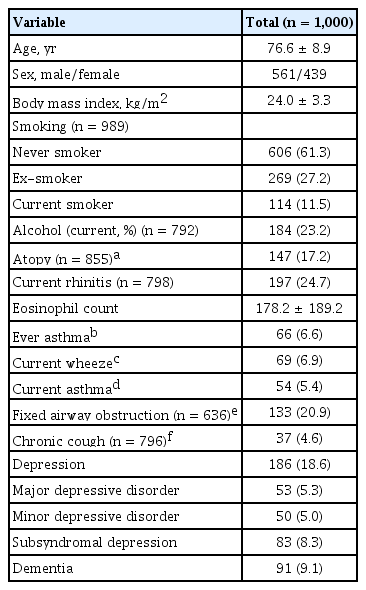

A total of 1,000 participants (mean age, 76.6 years) were enrolled. The baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. The prevalence rates of current asthma and MDD were 5.4% and 5.3%, respectively.

Association between asthma and depression in the elderly population

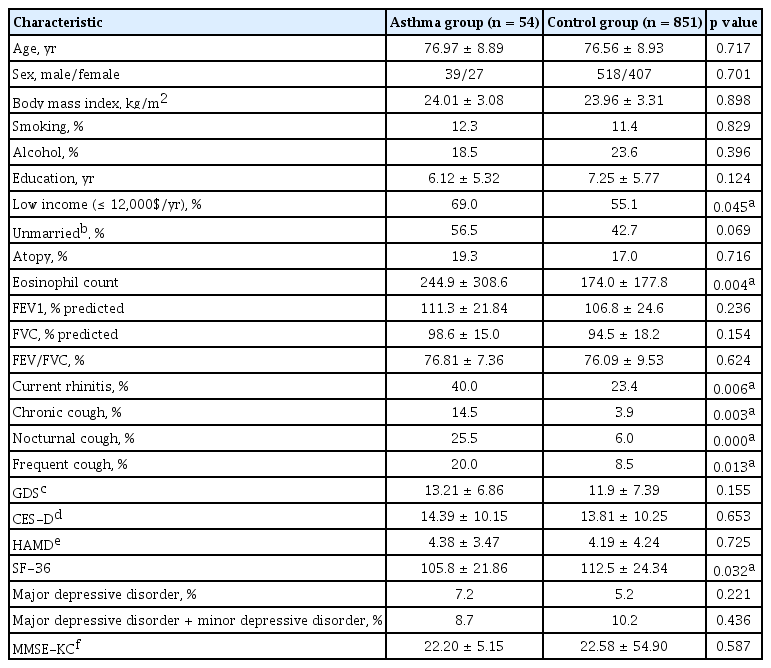

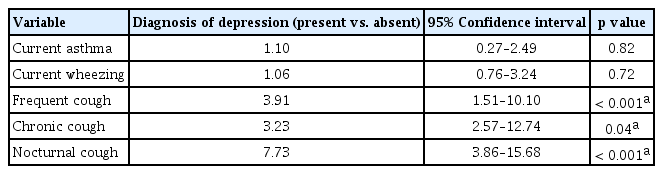

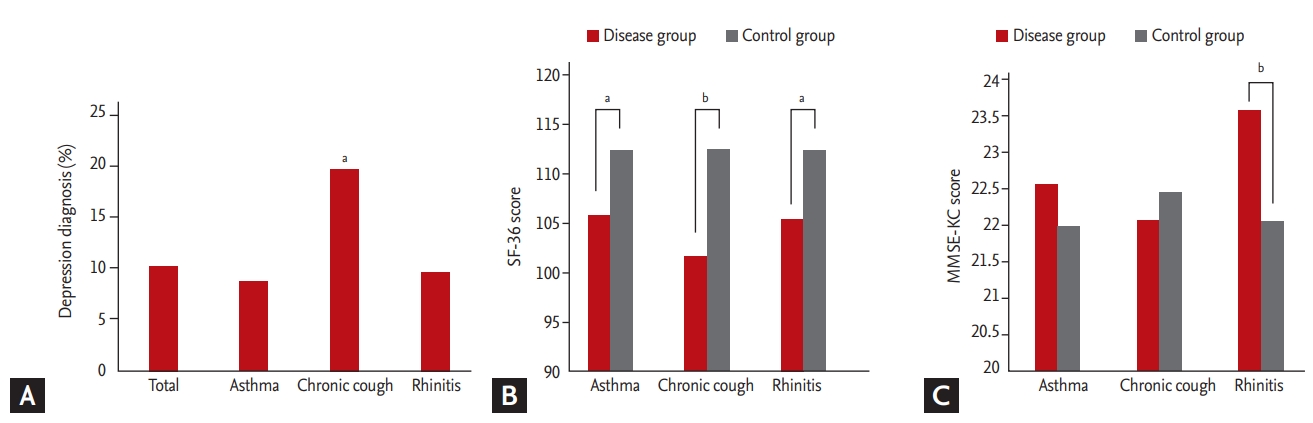

As shown in Table 2, asthma was not significantly associated with physician-diagnosed depression or any of the outcomes of depression (7.2% vs. 5.2%, p = 0.221). Asthma has a negative impact on the quality of life, but not on depression and cognitive function (Fig. 1). In a subgroup analysis, no difference was observed between the ever asthma and current wheeze groups in terms of GDS, CES-D, and HAM-D scores (p > 0.1, as calculated using the Pearson correlation test) (Supplementary Fig. 1). However, cough symptoms (frequent, chronic, or nocturnal cough) showed significant associations with various depression status scores, such as GDS, CES-D, and/or HAM-D scores (representative variable: frequent cough, GDS: p = 0.036; CES-D: p = 0.028; HAMD: p < 0.001). The HAM-D score was the most discriminating in the estimation of the association between depression and cough symptoms (frequent cough vs. control, 6.11 ± 5.40 vs. 4.01 ± 4.10, p < 0.001; chronic cough vs. control, 7.19 ± 6.38 vs. 4.06 ± 4.10, p < 0.001; nocturnal cough vs. control, 5.78 ± 4.92 vs. 4.07 ± 4.17, p = 0.004). In the multivariate logistic regression analyses, the diagnosis of depressive disorder (MDD and/or MDD + MnDD) was not significantly associated with asthma. However, it was associated with cough symptoms (frequent cough: odds ratio [OR], 3.91; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.51 to 10.10; chronic cough: OR, 3.23; 95% CI, 2.57 to 12.74; nocturnal cough: OR, 7.73; 95% CI, 3.86 to 15.68) (Table 3).

Influence of allergic airway disease on (A) diagnosis of depression, (B) quality of life (36-item short-form questionnaire [SF-36]), and (C) the dementia scales (Mini-Mental State Examination, Korean version [MMSE-KC]). ap < 0.05, bp < 0.001.

Association between rhinitis and the MMSE-KC score in the elderly population

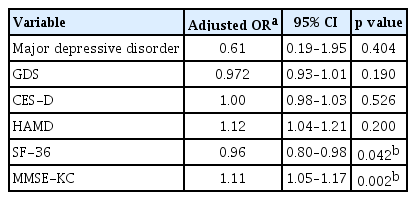

The prevalence rate of rhinitis in the elderly population was 32.8%. MDD showed a tendency toward a positive association with rhinitis (7.1% in participants with rhinitis vs. 4.9% in those without rhinitis). However, the result was not statistically significant (p = 0.258, data not shown). Rhinitis was associated with significantly lower SF-36 scores and higher MMSE-KC scores in multivariate analyses, which connotes that rhinitis had a negative effect on quality of life and a positive effect on cognitive function (Table 4). Atopic status and blood eosinophilia were not different between the depression and control groups.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed no statistically significant relationships between depression status and asthma and/or allergic conditions in the elderly population. Interestingly, cough symptoms, such as chronic cough, were significantly associated with depression and the quality of life in the elderly population.

Asthma has been considered psychosomatic disorder from unsolved inner conflict [29], which means that there might be a correlation between asthma and depression. More recent studies have shown that psychiatric patients with asthma had considerably more emergency visits, asthma exacerbations, and hospitalizations, including intensive care unit admissions and mechanical ventilation, which are all known as determinants of asthma-related medical costs [9,30,31]. Therefore, numerous studies have assessed the reciprocal interaction between depression and asthma. However, the study conclusions varied depending on the study design, sample size, and operational definition of asthma.

We hypothesized that asthma might be associated with depression in the elderly population. However, a statistically significant relationship was not observed between the diagnosis of asthma and depression or any depression scores. In this study, patients with asthma were selected from the general population in this study, it is possible that the patients had milder asthma than those who were selected from tertiary hospitals in previous studies [17,32]. Thus, we assessed participants whose presumed forced expiratory volume in 1 second was lower than 70% (n = 26); however, they also did not show any significant associations with the diagnosis and/or parameters of depression, and this supports the assumption that lung function has minimal impact on depression in the elderly population. Rather, cough, subjective symptoms, were significantly associated with depression status, which supports previous observations from case or case-control studies of patients with chronic cough [33,34]. Patients with chronic cough, nocturnal cough, and frequent cough were diagnosed as “current asthma” at 14.5%, 25.5%, and 20.0%, respectively; therefore, cough should be considered as an independent disease entity in elderly.

There is a misconception that asthma occurs as a childhood disease. Thus far, epidemiologic studies on depression and asthma have primarily targeted pediatric patients, and this indicates that asthma develops along with depression in children and adolescents [35-37]. Only few studies have investigated the association between depression and asthma in the elderly population, and the results were inconsistent. Choi et al. [17] reported that elderly individuals who are asthmatics had a higher rate of depression than young individuals who are asthmatics. Moreover, they had different risk factors for depression, which included obesity and smoking status. However, the study was not particularly well controlled because of the limitations in using hospital data, and the assessments for comorbid disorders and socioeconomic status were restricted. Dyer and Sinclair [18] have examined whether there is a poor association between depressive symptoms and asthma in hospitalized patients. However, selection bias could not be avoided in their study [18]. Lastly, Ng et al. [13] demonstrated that asthma in elderly individuals had a stronger association with depression in a population-based study after adjusting for confounders. They used a computerized diagnostic system called the Automated Geriatric Examination for Computer Assisted Taxonomy to diagnose depression, which is more inclusive of depressive disorders than the DSM-IV categories of major or minor depression. In the current study, neuropsychiatrists conducted age-, sex-, and education-standardized comprehensive diagnostic assessments using a one-step design and excluded patients with neuropsychiatric comorbidities. Comorbid neuropsychiatric conditions, such as dementia, stroke, or transient ischemic attack, and mood disorders are common disorders in elderly individuals, and these conditions are known to significantly influence depression [38].

In this population-based study of elderly participants, asthma in older adults was not associated with depression. A recent meta-analytic study has reported that adult-onset asthma did not increase the risk of depression based on prospective studies [39], and this finding supports the result of our study. We are considering the following hypothesis to explain these relationships. The heterogeneity and comorbid conditions in elderly individuals with asthma are major relevant factors. In a recent whole-genome study, individuals with asthma who presented with depression expressed higher levels of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway in CD4+ T cells, which supports the possibility that Th1/Th2 differentiation is associated with depressive asthma [40]. Unlike in children and young adults, the role of immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated atopy in elderly individuals with asthma is not fully elucidated. Instead, staphylococcal enterotoxin IgE sensitization [41], obesity [22], and smoking [42] are considered as major risk factors for asthma in elderly patients, which may be considerably distinct from those related to the disease in young adults. The different pathophysiology of childhood- and adult-onset asthma may be responsible for the differences in its association with depression. The secondary finding was interesting; cough symptoms were correlated with depression. Cough symptoms, rather than asthma itself, may play a role in the coexistence of depression in the elderly population, and clinicians should identify targets for assessing the impact of depression in elderly individuals with asthma.

The present analyses showed that rhinitis was not significantly associated with depression in the elderly population, irrespective of their atopic status. Moreover, rhinitis symptoms, such as rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, and nasal itching, have a worse impact on quality of life. Interestingly, rhinitis was positively associated with cognitive function, as measured using the MMSE-KC. The cognitive function of the controls and patients with symptomatic allergic rhinitis may not be significantly different in children and young adults [43,44]. However, information on the impact of rhinitis on cognitive function in the elderly population is limited. A recent study has reported that allergic diseases were associated with the beneficial effects on dementia and higher MMSE scores. Furthermore, the levels of IgG in the cerebrospinal fluid were lower in patients with Alzheimer’s disease but without allergic diseases [45]. Obtaining definitive conclusions was not possible in this study; therefore, future studies must be conducted to confirm the results of this study.

The present study has several limitations. First, our definition of asthma was based on self-reported asthma. Therefore, some cases of current asthma may present misreported data on asthma-like symptoms. However, self-reported asthma has been validated in epidemiologic studies of the elderly or adult population [15,21]. Second, since the study was conducted in an urban area, the results cannot be generalized to other elderly populations in rural areas due to selection bias. Finally, this is a cross-sectional study; therefore, we cannot identify the causal relationship between depression and asthma. However, a comprehensive analysis of a well-defined elderly population was conducted by professionals using standardized and structured diagnostic assessment tools for depression and comorbidities, and this is considered as the primary strength of the study. Another strength is that more than 25% of the participants were above 85 years of age, and this age group has rarely been included in previous studies.

In conclusion, there was no evidence that asthma was associated with depression in the elderly population, even when stratified by lung function. However, cough was associated with impairment in quality of life and depression in the elderly. For these reason, interventions aimed at improving the patients’ self-perceived respiratory symptoms, such as chronic cough, may be needed for elderly asthma control.

KEY MESSAGE

1. Depression is not significantly associated with asthma and rhinitis, but rather with chronic cough.

2. Management of respiratory symptoms, such as chronic and nocturnal cough, may be useful in controlling elderly asthma and improving their quality of life.

Supplementary Materials

Influence of allergic disease on scales of depression. (A) Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), (B) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), (C) Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD). To analyze the effects of allergy on scales of depression, analysis of variance was performed followed by univariate tests. The boxplots indicate interquartile range (IQR), the upper whisker is 1.5 IQR + Q3, the lower whisker is 1.5 IQR − Q1, and the line in the middle shows the median.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C2175).