INTRODUCTION

Castleman disease (CD) was first described in the 1950s as a rare nonmalignant lymphoproliferative disorder in patients with localized mediastinal lymphadenopathy [

1,

2]. CD is classified as multicentric (MCD) or unicentric (UCD) based on its anatomical distribution; MCD constitutes approximately 30% of all CD cases with high mortality [

3-

6]. In the general population, the incidence of UCD and MCD is 15 and 5 per million patients per year, respectively, with regional variations [

7].

MCD is characterized by systemic symptoms such as night sweats, fever, chills, fatigue, anorexia, anasarca, and cachexia. Its commonest features are enlarged lymph nodes at multiple anatomical sites, cytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, and increased concentrations of acute-phase proteins, such as fibrinogen and C-reactive protein (CRP) [

4,

8]. These apparently vague signs and symptoms result from the overproduction of interleukin 6 (IL-6), which plays a central role in the pathophysiology of MCD by inducing multiple processes such as the proliferation of B lymphocytes and plasma cells and the secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [

9].

Recent findings have elucidated the role of viral pathogenesis, particularly in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related cases. Viral IL-6 may trigger the development of MCD in HIV-seropositive patients. However, most patients with MCD are HIV-negative, and the role of human IL-6 in HIV-negative MCD is well established [

8,

10]. MCD may be subdivided according to its etiology into human herpes virus (HHV)-8-associated MCD, polyneuropathy, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, skin change-associated MCD, idiopathic MCD (iMCD), and MCD-like disorders [

11]. The etiology of iMCD is unknown, and owing to its rarity, the options for its treatment are limited. In symptomatic iMCD, the treatment options include administration of high-dose steroids, rituximab, or combined conventional chemotherapy regimens such as cyclophosphamide, adriamycin, vincristine, and prednisolone (CHOP).

Siltuximab is a human-mouse chimeric immunoglobulin G1╬║ monoclonal antibody against human IL-6. In a multicenter randomized and controlled phase 2 trial that included 79 HIV-negative iMCD patients, siltuximab with supportive care provided superior outcomes than supportive care alone, with tolerable safety and efficacy [

12,

13]. Furthermore, recently published consensus guidelines for the treatment of iMCD recommend siltuximab with or without corticosteroids as first-line therapy [

14].

In this study, we determined the efficacy and safety of siltuximab in 15 patients with MCD, of whom two experienced sustained disease regression on long-term follow-up. The 15 patients were carefully examined to exclude the presence of HIV or HHV-8 infection, in addition to other infectious diseases that mimic the signs and symptoms of MCD.

METHODS

Patients and study design

In this retrospective cohort analysis, we enrolled 15 patients with symptomatic iMCD who were eligible for siltuximab treatment between December 9, 2010 and October 31, 2018. Eligibility was based on detailed medical history, pathological diagnosis, and results of in-depth physical examinations, laboratory tests, and radiologic evaluation. The laboratory parameters examined from the time of diagnosis included the erythrocyte sedimentation rates (ESRs) and hemoglobin, CRP, creatinine, total protein, albumin, and ╬▓2-microglobulin levels. The presence of Epstein-Barr virus infection was assessed using the real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR). Radiological imaging included computed tomography (CT) of the neck, chest, and abdomen and positron emission tomography-CT; imaging was conducted at the time of diagnosis and every 3 months thereafter. In all cases of iMCD, the diagnosis was confirmed by a senior laboratory medicine physician with more than 10 years of experience. Pathological confirmation was based on lymph node biopsies and on the criteria established by a central pathology laboratory.

The symptoms at presentation were carefully assessed and classified individually based on the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTC-AE), version 4.0 and the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score. Some of the patients had received prior treatment; however, none had prior exposure to IL-6-targeted therapy. Patients were excluded if they were HIV-seropositive, had any evidence of HHV-8 infection on RQ-PCR in plasma or paraffin-embedded tissue, had clear evidence of a significant infection (e.g., hepatitis B or C), or had concurrent lymphoma.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board of Seoul at St. MaryŌĆÖs Hematology Hospital, Catholic University of Korea (KC19RESI0696) and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Treatment procedures and outcomes

All patients received an intravenous infusion of siltuximab (11 mg/kg) at 3-week intervals along with best supportive care, which included management of effusions, infections, transfusions, and infusion-related reactions; it also involved the administration of antipruritics, antihistamines, antipyretics, and analgesics according to standard institutional guidelines. All patients continued treatment until treatment failure, which was defined as the appearance of new disease-related grade Ōēź 3 symptoms, persistence of grade Ōēź 2 disease-related symptoms for more than 3 weeks, elevated (by more than 1 point) ECOG scores persisting for at least 3 weeks, and radiological progression based on the modified Cheson criteria [

15].

The primary endpoints included a durable symptomatic response and radiologic improvements for at least 3 months during treatment. Since there are no established criteria for evaluating iMCD, we used the modified Cheson criteria owing to the lymphoproliferative nature of iMCD.

Statistical analysis

The categorical variables were compared using the chisquare or FisherŌĆÖs exact tests, and continuous variables were assessed using the StudentŌĆÖs t test or Mann-Whitney U tests for comparison between the groups. Pearson analysis was employed for calculating the correlation coefficients. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and all p values reported are two-sided. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) software package.

DISCUSSION

This study reports real-world data based on the clinical experience with siltuximab in the treatment of symptomatic iMCD. We retrospectively assessed the efficacy and safety of siltuximab in HIV- and HHV8-negative Korean patients with iMCD in an actual clinical setting.

CD is a rare disease that comprises a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative disorders with characteristic histopathological appearances of lymph nodes ranging from atrophic germinal centers with hypervascularization to hyperplastic germinal centers with polytypic plasmacytosis [

16]. Unlike UCD, which involves a single enlarged lymph node, has relatively mild symptoms, and is curable by lymph node excision, MCD involves multicentric lymphadenopathy, systemic inflammation and related constitutional symptoms, cytopenia, and potentially fatal multiorgan failure, all of which result from a cytokine storm including IL-6 [

16]. The etiology of HHV-8- and HIV-negative iMCD is unknown, and the characteristics of this disease are considerably less well understood than those of HHV-8-associated MCD.

A working group of 42 international experts recently established evidence-based consensus treatment guidelines for iMCD; these guidelines recommended siltuximab infusion (11 mg/kg) at 3-week intervals with or without corticosteroids as first-line therapy in all cases of iMCD [

14]. This recommendation was based on the efficacy, safety, and patient responses to siltuximab, in addition to its global approval. The regimen involves continuation of siltuximab monotherapy for an indefinite period with tapering of corticosteroids. The disease severity in patients who fail to respond to siltuximab should be categorized based on disease status; severe iMCD may require intensive care and confers a high risk of multiorgan failure. According to the guidelines, patients with non-severe iMCD should receive 4 to 8 weekly doses of rituximab at a dose of 375 mg/m

2 with or without corticosteroids or immunosuppressive agents such as cyclosporin, sirolimus, tacrolimus, thalidomide, or bortezomib. In patients with severe iMCD, weekly administration of siltuximab is recommended at a dose of 11 mg/kg, with high-dose corticosteroids [

14].

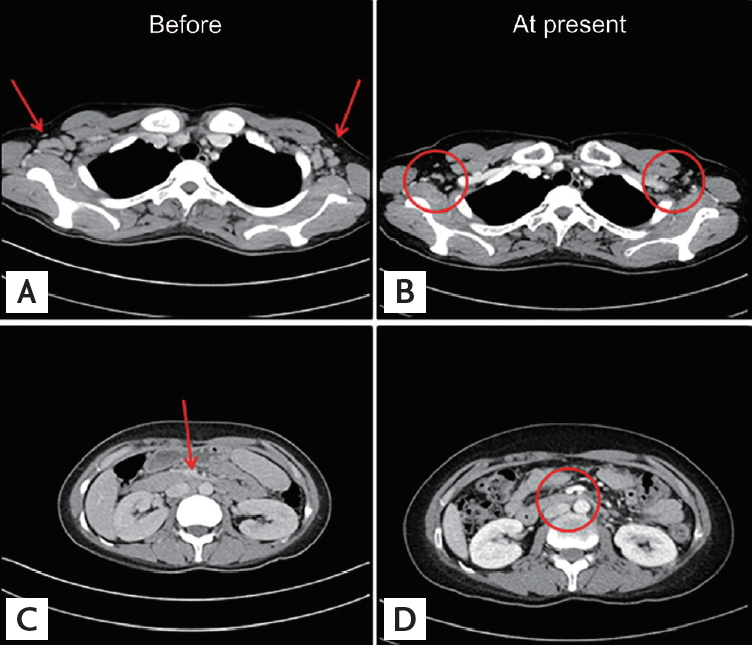

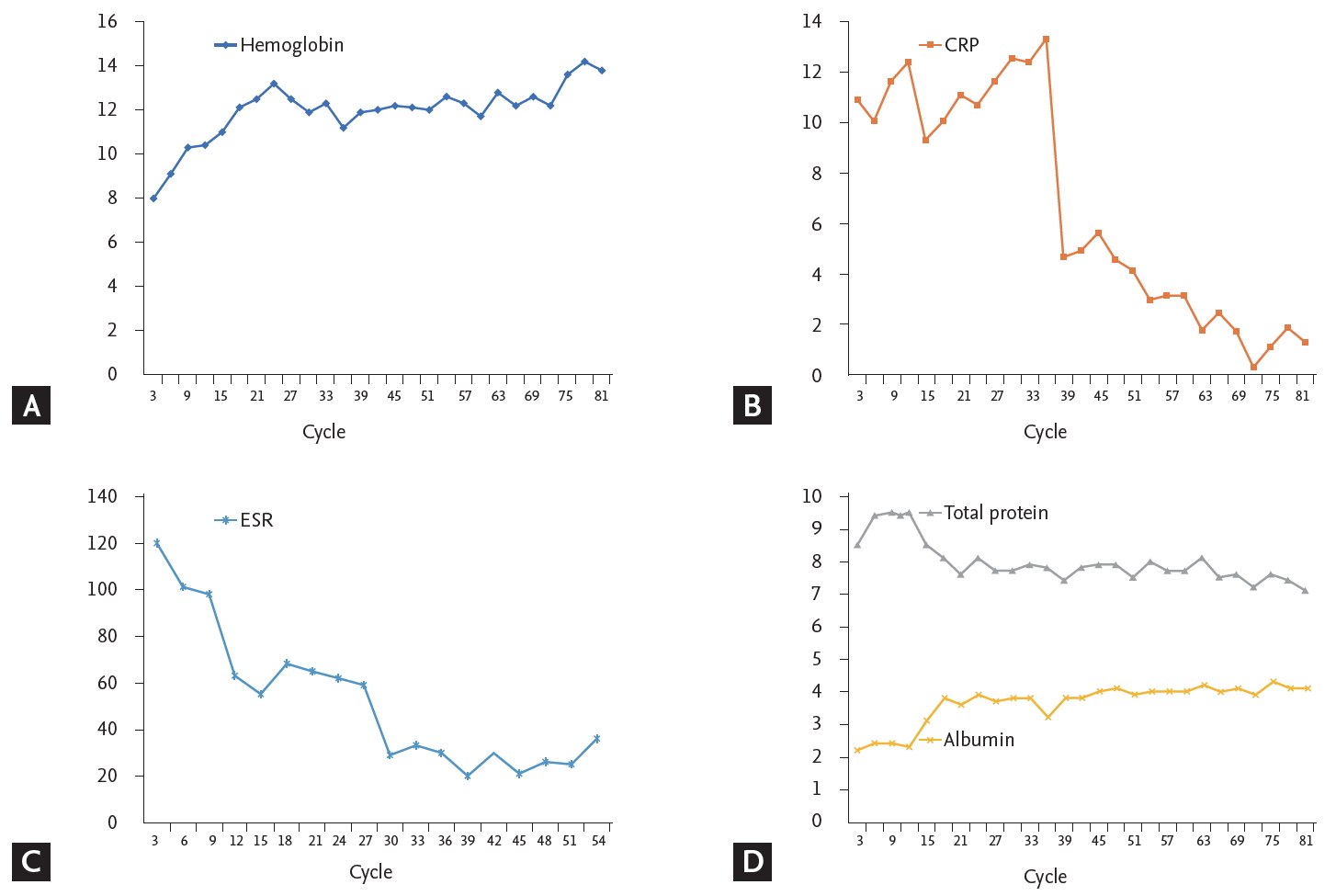

Overall, 64.7% of patients had a durable symptomatic response to siltuximab, with a median duration of response of 22 days (range, 17 to 56). The major laboratory indicators, including ESR, hemoglobin, and serum albumin concentrations, normalized rapidly within 3 months after treatment initiation. In contrast, lymph node involution, assessed using CT, occurred more gradually, with an overall response rate (CR + PR) of 66.7%. In responders, the timelines for the clinical, laboratory, and radiologic iMCD improvements were significantly different, requiring an average of one, three, and eight cycles of siltuximab treatment, respectively. Therefore, we recommend performing laboratory tests every 3 months. Radiologic evaluation should be performed every 6 months because as radiologic confirmation of CR requires at least 6 months from the initiation of siltuximab treatment. Additionally, although many patients showed rapid symptomatic responses after siltuximab treatment, additional intensive chemotherapy regimens may be considered in cases where symptoms are correlated with the iMCD mass effect, which improves considerably slowly compared to common constitutional symptoms.

Our study has certain limitations owing to the retrospective design and a small sample size. First, the treatment responses and symptomatic changes in particular were not assessed as rigorously as in a prospective study. Consequently, our findings with respect to treatment response and iMCD progression are less reliable and may not be generalizable to other populations. Second, owing to the retrospective design, a possibility of bias remains. Third, in the period when these patients underwent treatment, the treatment of iMCD was a challenge, and there were no evidence-based consensus guidelines or response evaluation criteria. Finally, although they represent a potential response criterion, the levels of IL-6, the key pathognomonic cytokine in iMCD, were not routinely assessed.

Although the Castleman Disease Collaborative Network has recently updated its guidelines [

14], there is still no consensus on the cessation of administration of immunomodulatory agents with or without steroids. In our experience, laboratory values in these patients recover significantly after four cycles (3 months) of siltuximab, reaching stable normal levels after about 80 cycles (60 months) of maintenance treatment (

Fig. 2). We speculate that radiologic CR should be a deciding factor for withholding siltuximab maintenance treatment because many real-world cases have shown delayed radiologic responses long after symptomatic relief and laboratory value normalization. The decision to discontinue maintenance treatment is a particular challenge for clinicians, and prospective cohort studies with long-term follow-up are essential for addressing this issue. Furthermore, as the siltuximab maintenance can be repeated until progression or toxicity, dose modification schedule might be inevitable. Unfortunately, because most of the siltuximab-treated patients only suffered from minor manageable adverse events, we did not attempt to reduce dosage or modify the intervals for siltuximab injection and followed U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved standard dose. Further dose modification studies involving a larger iMCD patient group will prove to be valuable. Because VEGF plays a major role in the development of constitutional symptoms [

12,

14,

16], the combination of a VEGF receptor inhibitor and siltuximab represents another viable therapeutic option in patients with moderate to severe symptomatic iMCD.

In conclusion, siltuximab with best supportive care improved the symptoms, laboratory values, and imaging findings in our hospital cohort of patients with symptomatic iMCD. Siltuximab demonstrated a favorable safety profile, and prolonged treatment with siltuximab was well-tolerated with no new or cumulative toxic effects or treatment discontinuations and few serious adverse events. Despite the small number of patients in this study, the results are encouraging and reinforce the potential of siltuximab in the first-line treatment of iMCD. Further studies are needed to elucidate the clinical outcomes and adverse events associated with siltuximab.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print