|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 36(2); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background/Aims

Methods

Results

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Table 2.

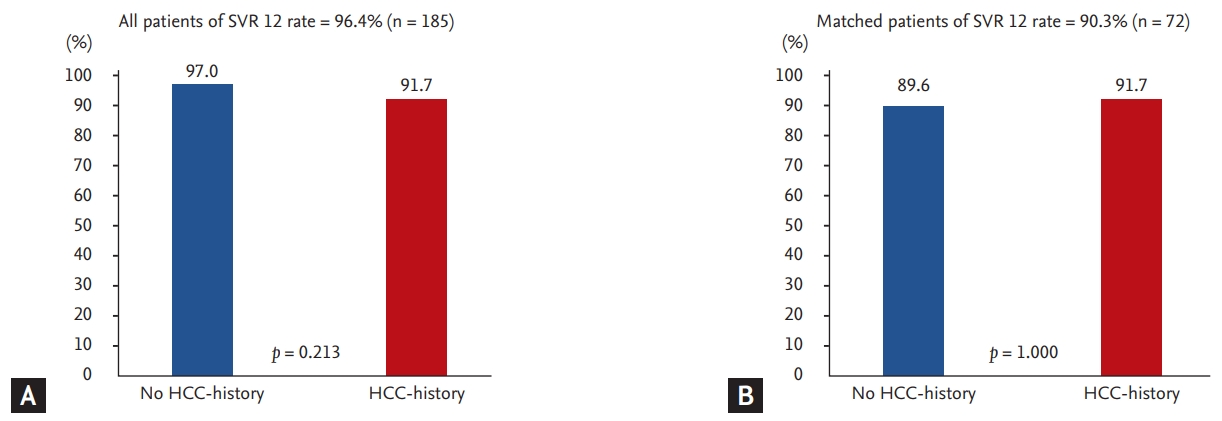

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Table 1.

| Variable | Total (n = 192) | Without HCC (n = 168) | With HCC (n = 24) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 59.0 (52.0–67.0) | 57.0 (51.0–64.0) | 72.0 (66.5–75.5) | < 0.001 |

| Female sex | 104 (54.2) | 95 (56.5) | 9 (37.5) | 0.125 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 23.6 (21.6–26.0) | 23.4 (21.1–25.5) | 24.6 (22.8–28.2) | 0.084 |

| HCV-RNA, IU/mL | 1,510,000.0 (289,000.0–4,580,000.0) | 1,575,000.0 (307,500.0–5,135,000.0) | 2,841,716.7 (166,800.0–3,855,000.0) | 0.612 |

| Genotype | 0.351 | |||

| 1 | 107 (55.7) | 91 (54.2) | 16 (66.7) | |

| 2 | 85 (44.3) | 77 (45.8) | 8 (33.3) | |

| DAA for genotype 1 | 0.001 | |||

| DCV + ASV | 57 (29.7) | 53 (31.6) | 4 (16.7) | |

| EBR + GZR | 22 (11.5) | 19 (11.3) | 3 (12.5) | |

| OBV/PTV/r + DSV | 13 (6.8) | 11 (6.5) | 2 (8.3) | |

| SOF + LDV | 10 (5.2) | 7 (4.2) | 3 (12.5) | |

| SOF + LDV + RBV | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.6) | 4 (16.7) | |

| DAA for genotype 2 | 0.018 | |||

| SOF + DCV | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 1 (4.2) | |

| SOF + LDV + RBV | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 | |

| SOF + RBV | 80 (41.7) | 73 (43.5) | 7 (29.2) | |

| GLE + PIB | 2 (1.0) | 2 (1.2) | 0 | |

| SVR 12 | 185 (96.4) | 163 (97.0) | 22 (91.7) | 0.213 |

| Prior IFN experienced | 42 (21.9) | 33 (19.6) | 9 (37.5) | 0.086 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 67 (34.9) | 44 (26.2) | 23 (95.8) | < 0.001 |

| LSM, kPaa | 7.4 (4.4–12.6) | 7.0 (4.4–11.5) | 17.4 (14.0–48.0) | 0.012 |

| FIB-4 | 3.0 (1.8–4.7) | 2.6 (1.6–4.1) | 9.2 (4.7–11.4) | < 0.001 |

| > 3.25 | 85 (44.7) | 62 (37.3) | 23 (95.8) | < 0.001 |

| CTP score | 0.064 | |||

| A | 163 (84.9) | 143 (94.7) | 20 (83.3) | |

| B | 12 (6.3) | 8 (5.3) | 4 (16.7) | |

| MELD score | 0.182 | |||

| < 9 | 123 (73.7) | 110 (75.9) | 13 (59.1) | |

| 10–19 | 40 (24.0) | 32 (22.1) | 8 (36.4) | |

| 20–29 | 4 (2.4) | 3 (2.1) | 1 (4.6) | |

| AFP, ng/mL | 4.9 (3.0–9.2) | 4.4 (2.8–8.6) | 8.2 (6.2–31.1) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol | 41 (21.4) | 37 (22.0) | 4 (16.7) | 0.739 |

| Side effect | 68 (35.4) | 60 (35.7) | 8 (33.3) | 1.000 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; BMI, body mass index; HCV-RNA, hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid; DCV, daclatasuvir; ASV, asunaprevir; EBR, elbasvir; GZR, grazoprevir; OBV, ombitasvir; PTV, paritaprevir; r, ritonavir; DSV, dasabuvir; SOF, sofosbuvir; LDV, ledipasvir; RBV, ribavirin; GLE, glecaprevir; PIB, pibrentasvir; SVR 12, sustained viral response at 12 weeks; IFN, interferon; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD, model for End-stage Liver Disease; AFP, α-fetoprotein.

Table 2.

| Variable | Total (n = 72) | Without HCC (n = 48) | With HCC (n = 24) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 71.0 (63.0–76.5) | 70.8 (63.0–77.5) | 71.0 (66.5–75.5) | 0.886 |

| Female sex | 24 (33.3) | 15 (31.3) | 9 (37.5) | 0.596 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 24.1 (22.4–26.0) | 23.6 (22.0–25.4) | 25.1 (22.7–28.3) | 0.142 |

| HCV-RNA, IU/mL | 980,000.0 (96,800.0–4,400,000.0) | 3,367,365.0 (92,200.0–5,180,000.0) | 2,841,716.7 (166,800.0–3,855,000.0) | 0.693 |

| Genotype | 0.729 | |||

| 1 | 46 (63.9) | 30 (62.5) | 16 (66.7) | |

| 2 | 26 (36.1) | 18 (37.5) | 8 (33.3) | |

| DAA for genotype 1 | 0.025 | |||

| DCV + ASV | 20 (27.8) | 16 (33.3) | 4 (16.7) | |

| EBR + GZR | 11 (15.3) | 8 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | |

| OBV/PTV/r + DSV | 6 (8.3) | 4 (8.3) | 2 (8.3) | |

| SOF + LDV | 5 (6.9) | 2 (4.2) | 3 (12.5) | |

| SOF + LDV + RBV | 4 (5.6) | 0 | 4 (16.7) | |

| DAA for genotype 2 | 0.256 | |||

| SOF + DCV | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (4.2) | |

| SOF + LDV + RBV | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.1) | 0 | |

| SOF + RBV | 24 (33.3) | 17 (35.4) | 7 (29.2) | |

| SVR 12 | 65 (90.3) | 43 (89.6) | 22 (91.7) | 1.000 |

| Prior IFN experienced | 21 (29.2) | 12 (25.0) | 9 (37.5) | 0.271 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 41 (56.9) | 18 (37.5) | 23 (95.8) | < 0.001 |

| LSM, kPaa | 7.7 (5.2–14.0) | 6.7 (4.4–11.8) | 17.4 (14.0–48.0) | 0.024 |

| FIB-4 | 4.4 (3.1–10.2) | 3.9 (2.3–5.3) | 9.2 (4.7–11.4) | < 0.001 |

| > 3.25 | 52 (73.2) | 29 (61.7) | 23 (95.8) | 0.005 |

| CTP score | 0.715 | |||

| A | 56 (86.2) | 36 (87.8) | 20 (83.3) | |

| B | 9 (13.8) | 5 (12.2) | 4 (16.7) | |

| MELD score | 1.000 | |||

| < 9 | 38 (61.3) | 25 (62.5) | 13 (59.1) | |

| 10–19 | 22 (35.5) | 14 (35.0) | 8 (36.4) | |

| 20–29 | 2 (3.2) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.6) | |

| AFP, ng/mL | 7.1 (3.3–14.0) | 4.6 (2.8–10.8) | 8.2 (6.2–31.1) | 0.012 |

| Alcohol | 17 (23.6) | 13 (27.1) | 4 (16.7) | 0.492 |

| Side effect | 23 (31.9) | 15 (31.3) | 8 (33.33) | 0.858 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BMI, body mass index; HCV-RNA, hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; DCV, daclatasuvir; ASV, asunaprevir; EBR, elbasvir; GZR, grazoprevir; OBV, ombitasvir; PTV, paritaprevir; r, ritonavir; DSV, dasabuvir; SOF, sofosbuvir; LDV, ledipasvir; RBV, ribavirin; SVR 12, sustained viral response at 12 weeks; IFN, interferon; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; AFP, α-fetoprotein.

Table 3.

| Variable | Without HCC (n = 168) | With HCC (n = 24) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 60 (35.7) | 8 (33.3) | 0.176 |

| Genotype 1 | 19 (11.3) | 3 (12.5) | |

| Genotype 2 | 41 (24.4) | 5 (20.8) | |

| Discontinuation of treatment | 0 | 0 | |

| Anemiaa | 35 (20.8) | 4 (16.7) | |

| Dyspepsia | 5 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Insomnia | 4 (2.4) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Fatigue | 7 (4.2) | 0 | |

| Tingling sensation | 0 | 2 (8.3) | |

| Arrhythmic events | 2 (1.2) | 0 | |

| Cough | 1 (0.6) | 0 | |

| Minority events | 6 (3.6)a | 1 (4.2)c |

Table 4.

| Variable | No recurrence (n = 10) | Recurrence (n = 14) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 69.0 (63.0–73.0) | 73.5 (71.0–78.0) | 0.069 |

| Female sex | 5 (50.0) | 4 (28.6) | 0.403 |

| BMI, kg/m² | 23.4 (21.6–24.2) | 26.3 (23.7–28.3) | 0.069 |

| HCV-RNA, IU/mL | 1,031,000.0 (568,000.0–8,230,000.0) | 1,827,500.0 (93,600.0–3,560,000.0) | 0.837 |

| Genotype | 1.000 | ||

| 1 | 7 (70.0) | 9 (64.3) | |

| 2 | 3 (30.0) | 5 (35.7) | |

| DAA for genotype 1 | 0.126 | ||

| DCV + ASV | 0 | 4 (44.4) | |

| EBR + GZR | 3 (42.9) | 0 | |

| OBV/PTV/r + DSV | 1 (14.3) | 1 (11.1) | |

| SOF + LDV | 1 (14.3) | 2 (22.2) | |

| SOF + LDV + RBV | 2 (28.6) | 2 (22.2) | |

| DAA for genotype 2 | 0.783 | ||

| SOF + DCV | 1 (33.3) | 0 | |

| SOF + RBV | 2 (66.7) | 5 (100.0) | |

| SVR 12 | 10 (100.0) | 12 (85.7) | 0.493 |

| Prior IFN experienced | 0 | 9 (64.3) | 0.002 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 9 (90.0) | 14 (100.0) | 0.417 |

| FIB-4 | 4.8 (4.5–9.1) | 10.8 (6.7–15.1) | 0.064 |

| > 3.25 | 10 (100.0) | 13 (92.9) | 1.000 |

| CTP score | 1.000 | ||

| A | 8 (80.0) | 12 (85.7) | |

| B | 2 (20.0) | 2 (14.3) | |

| MELD-NA score | 0.814 | ||

| < 9 | 7 (70.0) | 6 (50.0) | |

| 10–19 | 3 (30.0) | 5 (41.7) | |

| 20–29 | 0 | 1 (8.3) | |

| AFP before DAA | 9.9 (6.2–24.3) | 7.7 (5.7–37.9) | 0.305 |

| PIVKA II before DAA | 14.8 (11.0–22.8) | 18.0 (13.0–19.5) | 0.926 |

| HCC treatment | 0.780 | ||

| Curativea | 5 (50.0) | 5 (35.7) | |

| Palliativeb | 5 (50.0) | 9 (64.3) | |

| BCLC stage | 0.629 | ||

| 0 state | 3 (30.0) | 5 (35.7) | |

| A stage | 7 (70.0) | 8 (57.1) | |

| B stage | 0 | 1 (7.1) | |

| mUICC stage | 0.773 | ||

| 1 stage | 3 (30.0) | 5 (35.7) | |

| 2 stage | 5 (50.0) | 5 (35.7) | |

| 3 stage | 2 (20.0) | 4 (28.6) | |

| Maximum tumor size, cm | 2.2 (1.4–2.5) | 2.0 (1.4–2.4) | 0.769 |

| HCC nodules | 0.678 | ||

| 1 | 8 (80.0) | 10 (71.4) | |

| 2 | 2 (20.0) | 3 (21.4) | |

| 3 | 0 | 1 (7.1) | |

| From last HCC treatment to DAA treatment, day | 188.5 (54.0–619.0) | 214.0 (70.0–645.0) | 0.883 |

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BMI, body mass index; HCV-RNA, hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; DCV, daclatasuvir; ASV, asunaprevir; EBR, elbasvir; GZR, grazoprevir; OBV, ombitasvir; PTV, paritaprevir; r, ritonavir; DSV, dasabuvir; SOF, sofosbuvir; LDV, ledipasvir; RBV, ribavirin; SVR 12, sustained viral response at 12 weeks; IFN, interferon; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD-NA, model for end-stage liver disease with incorporation of serum sodium; AFP, α-fetoprotein; PIVKA II, Protein Induced by Vitamin K Absence or Antagonist-II; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; mUICC, modified Union for International Cancer Control.

Table 5.

| Variable |

Recurrence |

Occurrence |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Univariate |

Multivariate |

Univariate |

Multivariate |

|||||

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age, yr | 1.13 (0.98–1.30) | 0.085 | 1.10 (1.01–1.19) | 0.021 | 1.12 (1.02–1.23) | 0.021 | ||

| Sex, male vs. female | 2.50 (0.46–13.65) | 0.290 | 5.45 (0.60–49.83) | 0.133 | ||||

| BMI | 1.48 (0.97–2.27) | 0.067 | 1.34 (1.00–1.80) | 0.049 | 1.34 (0.99–1.82) | 0.057 | ||

| HCV-RNA | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.210 | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.192 | ||||

| Genotype, 2 vs. 1 | 1.30 (0.23–7.38) | 0.770 | 0.78 (0.13–4.81) | 0.791 | ||||

| SVR 12 | 4.20 (0.09–190.18) | 0.461 | 35.56 (4.26–297.10) | 0.001 | 8.12 (0.55–120.84) | 0.128 | ||

| Prior IFN experienced | 36.26 (1.51–872.74) | 0.027 | 36.26 (1.51–872.74) | 0.027 | 0.35 (0.02–6.84) | 0.492 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | 4.65 (0.05–471.65) | 0.515 | 4.46 (0.72–27.65) | 0.108 | ||||

| FIB-4 | 1.19 (0.97–1.46) | 0.100 | 1.09 (0.96–1.25) | 0.199 | ||||

| AFP before DAA | 0.99 (0.98–1.01) | 0.364 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 0.019 | ||||

| CTP score A vs. B | 1.50 (0.17–12.94) | 0.712 | 0.55 (0.02–13.03) | 0.710 | ||||

| HCC treatment, Curativea vs. palliativeb | 0.57 (0.11–2.90) | 0.486 | ||||||

| MELD-NA score | ||||||||

| 10–19 vs. < 9 | 1.81 (0.30–10.87) | 0.983 | 1.46 (0.20–10.57) | 0.773 | ||||

| 20–29 vs. < 9 | 3.49 (0.03–369.44) | 0.687 | 4.39 (0.12–158.16) | 0.478 | ||||

| BCLC stage | ||||||||

| Stage A vs. 0 | 0.72 (0.13–4.13) | 0.621 | ||||||

| Stage B vs. 0 | 1.91 (0.02–220.36) | 0.730 | ||||||

| mUICC stage | ||||||||

| Stage 2 vs. 1 | 0.60 (0.10–3.99) | 0.478 | ||||||

| Stage 3 vs. 1 | 1.20 (0.13–11.05) | 0.659 | ||||||

| Maximum tumor size | 1.38 (0.53–3.56) | 0.509 | ||||||

| No. of HCC nodules | ||||||||

| 2 vs. 1 | 1.13 (0.15–8.46) | 0.826 | ||||||

| 3 vs. 1 | 2.48 (0.02–257.21) | 0.722 | ||||||

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; HCV-RNA, hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid; SVR 12, sustained viral response at 12 weeks; IFN, interferon; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; AFP, α-fetoprotein; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD-NA, model for end-stage liver disease with incorporation of serum sodium; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; mUICC, modified Union for International Cancer Control.

Table 6.

Values are presented as median (interquartile range) or number (%).

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BMI, body mass index; HCV-RNA, hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; DCV, daclatasuvir; ASV, asunaprevir; EBR, elbasvir; GZR, grazoprevir; OBV, ombitasvir; PTV, paritaprevir; r, ritonavir; DSV, dasabuvir; SOF, sofosbuvir; LDV, ledipasvir; RBV, ribavirin; SVR 12, sustained viral response at 12 weeks; IFN, interferon; FIB-4, fibrosis-4; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD-NA, model for end-stage liver disease with incorporation of serum sodium; AFP, α-fetoprotein.

REFERENCES

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Dermatomyositis associated with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma2014 March;29(2)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement 1

Supplement 1 Print

Print