|

|

|

|

|

Abstract

Background/Aims

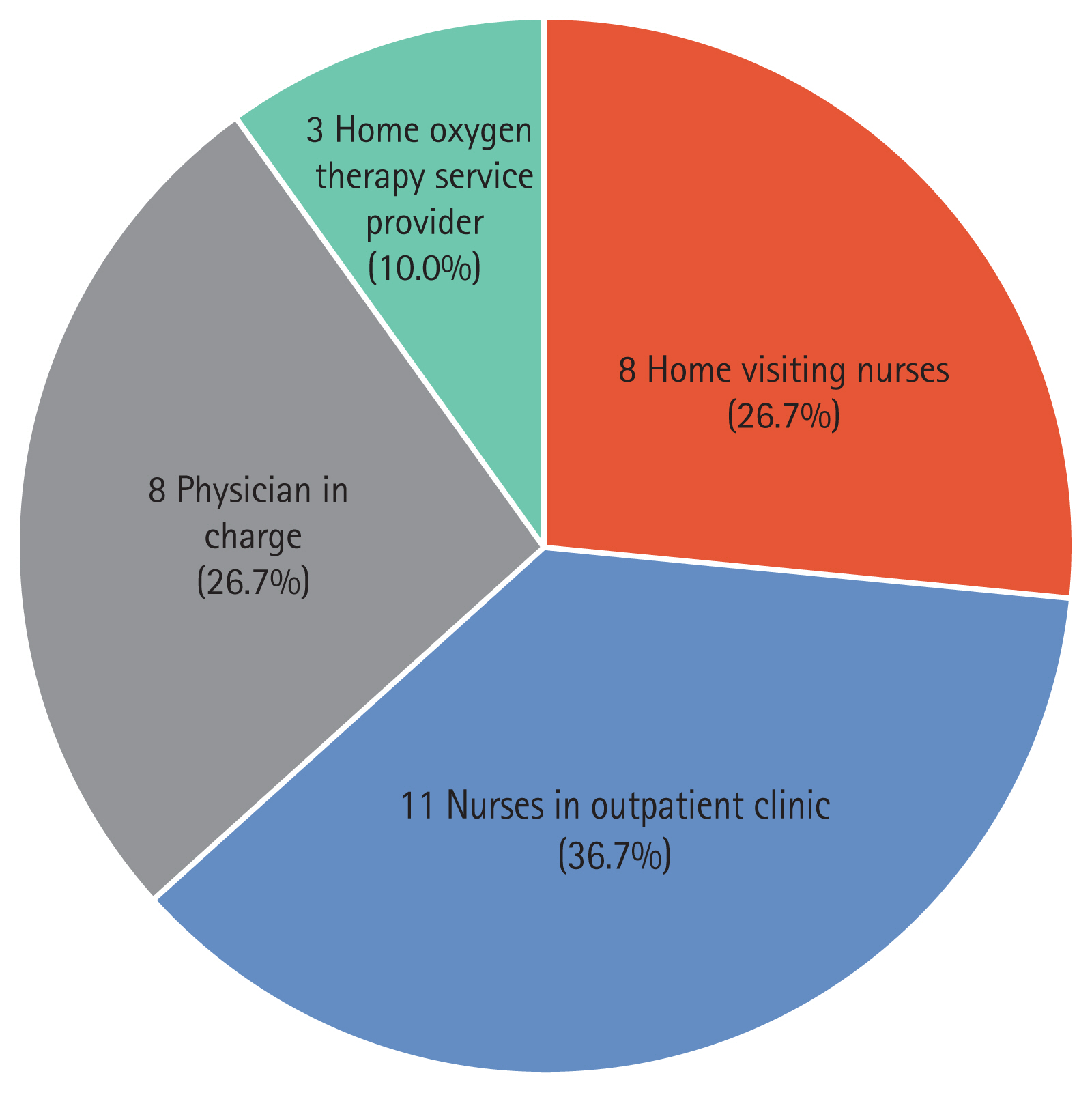

Hypoxemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) leads to reduced ability to exercise, decreased quality of life, and, eventually, increased mortality. Home oxygen therapy in patients with severe COPD reduces distress symptoms and mortality rates. However, there have been few studies on physicians’ prescription behavior toward home oxygen therapy. Therefore, we investigated the respiratory specialists’ perspective on home oxygen therapy.

Methods

In this cross-sectional, study, a questionnaire was completed by 30 pulmonary specialists who worked in tertiary hospitals and prescribed home oxygen therapy. The questionnaire consisted of 28 items, including 15 items on oxygen prescription for outpatients, four for inpatients, and nine on service improvement.

Results

All physicians were prescribing less than 2 L/min of oxygen for either 24 (n = 10, 33.3%) or 15 hours (n = 9, 30.3%). All (n = 30) used pulse oximetry, 26 (86.7%) analyzed arterial blood gas. Thirteen physicians had imposed restrictions and recommended oxygen use only during exercise or sleep. Sixteen (53.3%) physicians were educating their patients about home oxygen therapy. Furthermore, physicians prescribed home oxygen to patients that did not fit the typical criteria for long-term oxygen therapy, with 30 prescribing it for acute relief and 17 for patients with borderline hypoxemia.

Conclusions

This study identified the prescription pattern of home oxygen therapy in Korea. Respiratory physicians prescribe home oxygen therapy to hypoxemic COPD patients for at least 15 hours/day, and at a rate of less than 2 L/min. More research is needed to provide evidence for establishing policies on oxygen therapy in COPD patients.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a high morbidity and mortality disease in Korea and worldwide [1]. As COPD progresses, the risk of alveolar hypoxia and consequent hypoxemia increases [2], with hypoxemia leading to a decrease quality of life, reduced ability to exercise, and deteriorated skeletal muscle function. Severe hypoxemia in patients with end-stage COPD is highly associated with an increased mortality rate [3–5].

Long-term home oxygen therapy (LTOT) is recommended for patients with chronic respiratory conditions if their arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) is at least 55 mmHg or oxygen saturation (SaO2) is less than 88%, or if PaO2 is between 55 and 60 mmHg or SaO2 is 89%, with pulmonary hypertension, peripheral edema from congestive heart failure, or erythrocytosis (hematocrit > 55%) [6]. If LTOT is performed for more than 15 hr/day, the survival rate is improved [7]. In addition, home oxygen therapy is essential for improving the respiratory symptoms and quality of life in patients with COPD [8]. In Korea, the expense of LTOT has been reimbursed by national health insurance since 2006 if the patients’ condition meets the above criteria [9].

Despite several reports about the efficacy of oxygen therapy to patients [7,8,10], studies about the physicians’ prescription pattern of oxygen therapy in real practice are limited. One international survey conducted in 2001 on respiratory physicians who prescribed home oxygen, described the prescription pattern differences among countries [11]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide physicians’ views about home oxygen therapy in Korea. The purpose of this survey was to explore the respiratory specialists’ perspectives about home oxygen therapy.

In this cross-sectional survey-based study, we enrolled 30 pulmonary specialists and members of the Korea Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Subgroup Study (KOCOSS) group. None were involved in the questionnaire development. The survey was carried out via a web-based questionnaire from March 22 to March 30, 2016. After requesting the selected respiratory physician to participate in the survey, the questionnaire link was sent to the consenting participants.

The questionnaire used in this study was created by seven respiratory specialists participating in the KOCOSS cohort [12]. The questionnaire consisted of 28 items, including 15 items on oxygen prescription for outpatients, four items on inpatients prescription, and nine items on improving home oxygen treatment services. The questionnaire included specific physician examinations of the patients, and the timeframe of oxygen use at home during resting, exercise, or sleep. There were also questions about re-evaluation and home education after oxygen prescription. The questions on re-evaluation were mainly related to the necessity of home oxygen therapy, that is, the follow-up duration of home oxygen therapy, the diagnostic modality at follow-up, and any link with home care services. The Korean full version and English short version of questionnaire are attached in Appendices 1 and 2.

As the SaO2 criteria [6] for long-term oxygen therapy corresponded to moderate or severe hypoxemia [13], the participants were asked about their experiences prescribing oxygen to the patients with borderline hypoxemia. The definition of “borderline hypoxemia” used in this study was a SaO2 level that ranged between 92% to 93%. A SaO2 level between 90% and 94%, or 89% and 93%, was defined as mild hypoxemia [13] or moderate resting desaturation [10], respectively. We chose the range of SaO2 closest to the normal level. The full Korean version and short English version of the questionnaire are available in the supplementary section.

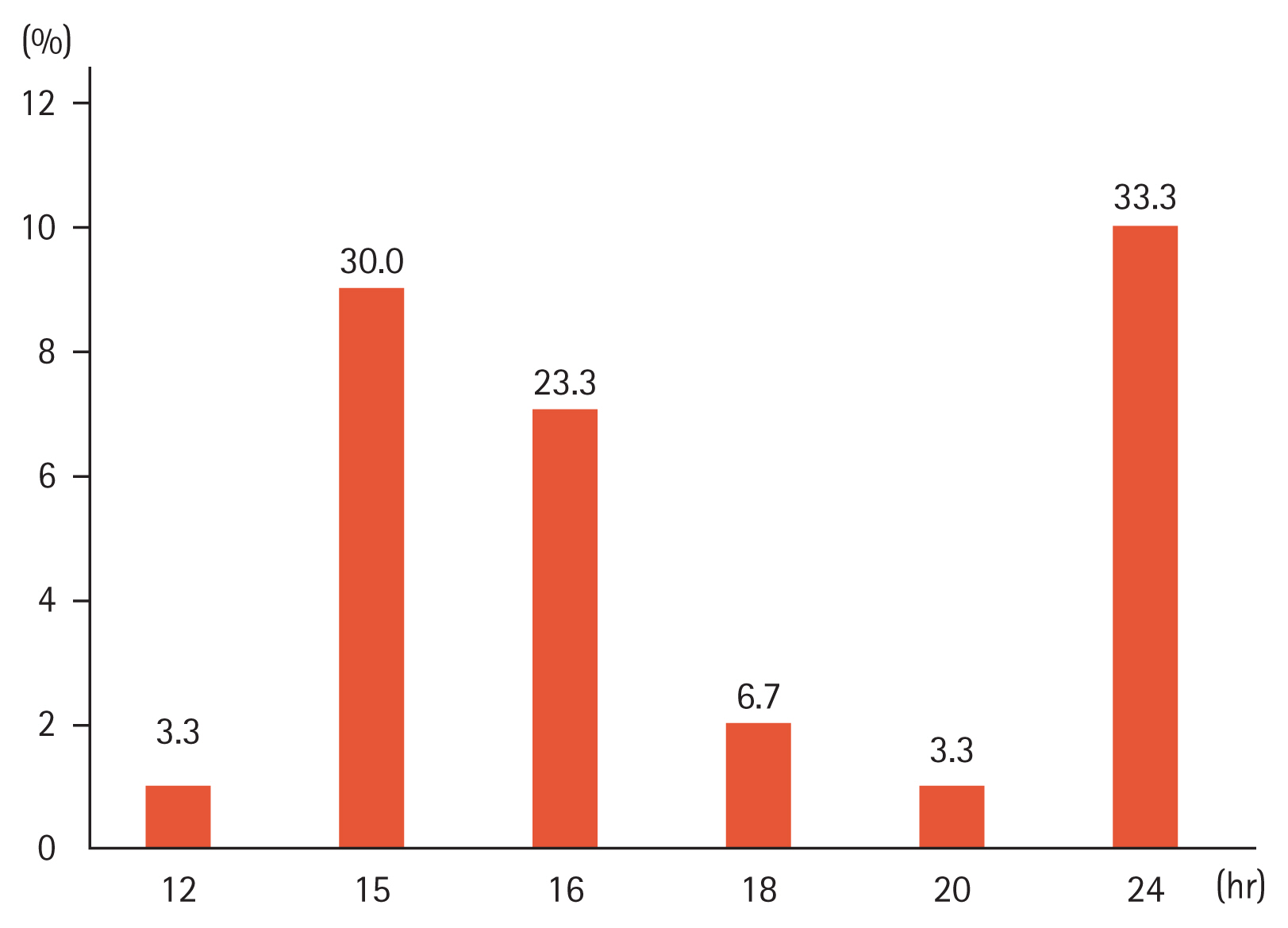

All 30 physicians confirmed they had issued more than one oxygen prescription per month on average: 19 physicians prescribed an average of 1 to 5 case/month (63.3%) and 11 prescribed 5 to 10 case/month (36.7%). All physicians included pulse oximetry when they issued oxygen prescriptions, and 26 physicians (86.7%) performed arterial blood gas analysis. A 6-minute walk test and pulmonary function test were used as adjunctive tests by, respectively, three (10.0%) and two (6.6%) physicians. The number of oxygen saturation measurements before oxygen prescription varied, with 11 physicians (36.7%) performing only once and 14 (46.7%) performing twice (Table 1). In terms of the initial oxygen flow, all 30 physicians prescribed less than 2 L/min, and of these physicians, 14 (46.7%) prescribed 1 L/min, and 16 (53.3%) prescribed 2 L/min. The physicians initially prescribed the oxygen use time as follows: Ten physicians (33.3%) initially prescribed for 24 hours, and nine physicians (30.3%) for 15 hours (Fig. 1). The maintenance of oxygen saturation was the primary determinant for the oxygen flow rate, and the physician prescribed the initial duration for oxygen use. However, approximately 25% of all physicians prescribed oxygen according to the patient’s condition (Supplementary Table 1).

Thirteen (43.3%) of the physicians replied that they restricted the use of oxygen (Table 2). For patients during exercise, 22 physicians prescribed the same flow rate used at resting state (73.3%), and the remaining adjusted the flow rate in various ways, such as modification according to the result of the 6-minute walk test by merely increasing the flow rate from the resting state (Table 2). In addition, 19 respiratory physicians prescribed the same flow rate as that use during sleep, seven used the reference to previous oxygen saturation during the night-time, three increased the flow rate than rest, and one reduced it to less than resting state during sleep (Table 2).

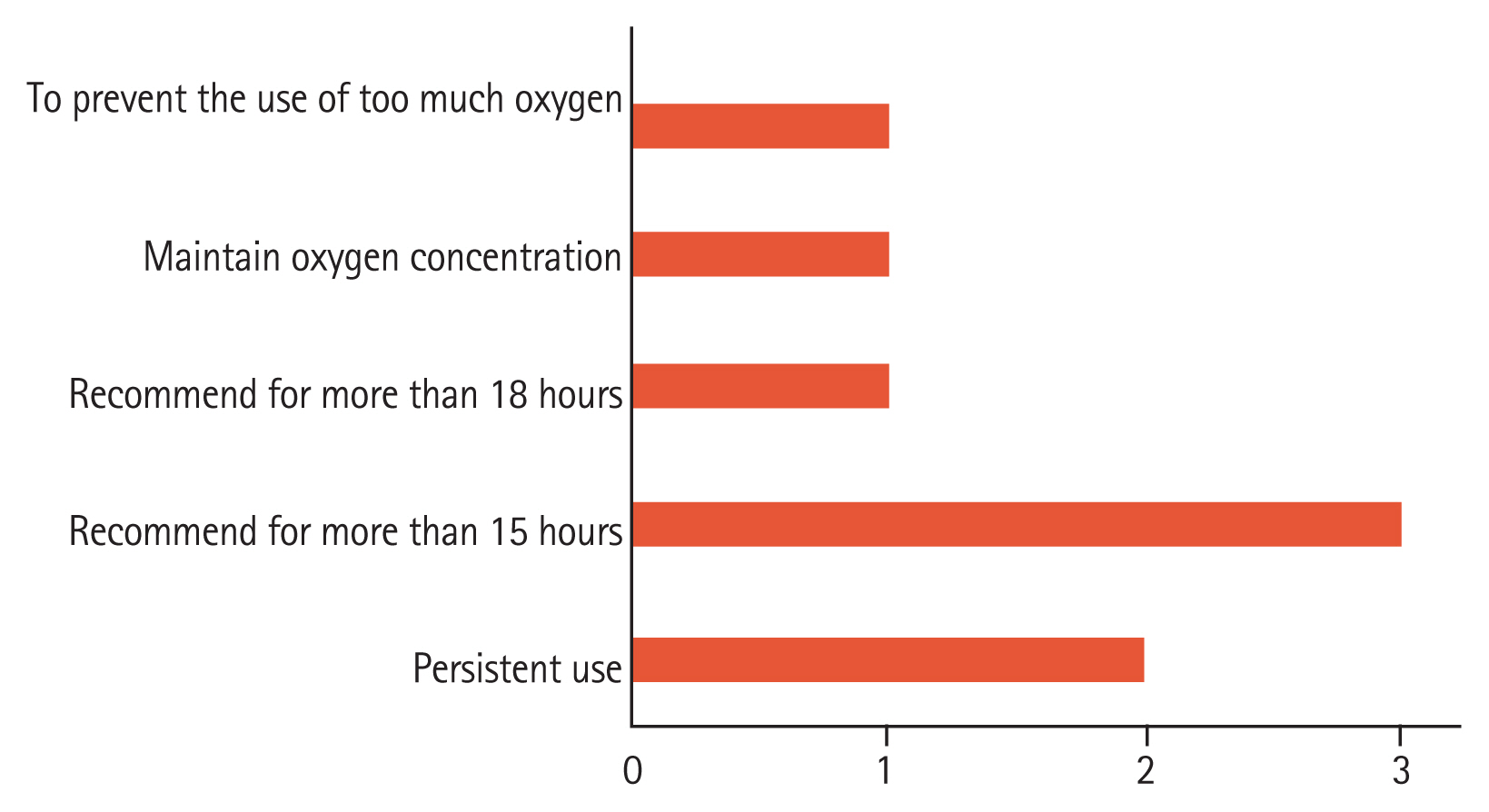

Sixteen (53.3%) physicians educated their patients about home oxygen therapy when they issued the oxygen prescription, with eight (50.0%) having educational material about home oxygen therapy (Table 3). All eight physicians had ‘leaflets provided by home oxygen therapy service providers,’ and one (12.5%) had ‘self-made educational materials in hospital’ (Table 3). Eight physicians who did not have educational materials answered that they referred to the time usage of oxygen. Two advised to use home oxygen therapy persistently or educate their patients not to use too much oxygen (Fig. 2). Fourteen physicians answered that they did not educate about home oxygen and provided the following explanations: 13 did not have enough time to educate during the outpatient clinic consultation (43.3%), eight answered that there was no one to educate (26.7%), and eight did not have any education material (26.7%) (Table 3).

Eighteen physicians (60.0%) re-assessed the need for home oxygen therapy for their patients. Most re-evaluated within 3 to 6 months, and the re-evaluation was confirmed using pulse oximetry (n = 16, 88.9%) or arterial blood gas analysis (n = 10, 55.6%) (Table 4).

Seventeen physicians answered that they had issued an oxygen prescription for borderline hypoxemia (n = 17, 56.7%). However, generally, they recommended only to use during exercise (n = 13, 76.5%) or periods of dyspnea (n = 4, 23.5%) (Table 2).

The patients with borderline hypoxemia were prescribed the same flow rate at rest (n = 10, 58.8%) or the flow rate in which hypoxemia was not observed while the patients underwent the 6-minute walk exam (n = 7, 41.2%) (Table 2). Conversely, for oxygen therapy during sleep, 11 physicians prescribed the same as at rest, three prescribed higher than at resting state, and two considered the previous saturation as a reference (Table 2).

All 30 physicians had had the experience of prescribing oxygen to patients discharged from the hospital after treatment for acute respiratory distress. Furthermore, all the physicians prescribed home oxygen therapy to patients with chronic respiratory disease (e.g., COPD, interstitial lung disease, lung cancer, bronchiectasis), as well as congestive heart failure, palliative, and end-of-life care diseases (Supplementary Table 2). Nine physicians advised using home oxygen therapy only during exercise, sleep, or periods of dyspnea (Supplementary Table 3). Nineteen physicians (63.3%) re-evaluated the home oxygen prescribed to patients after discharge, generally, within 3 months (n = 13. 68.4%) (Supplementary Table 4), and eight (72.7%) had difficulties re-evaluating due to lack of outpatient time (Supplementary Table 4).

In this study, we explored the real-world situation of physician oxygen prescription patterns. We asked the respiratory physicians who were prescribing the home oxygen about their prescription patterns. The 30 respiratory physicians who participated in the survey recommended their patients to use home oxygen for a minimum of 15 hours/day. This prescription pattern was in line with previous reports, which concluded that continuous home oxygen for 15 hours/day improved the survival rate and the quality of life [7,14]. In terms of flow rate, which has not yet been established, we found that most physicians prescribed less than 2 L/min initially. It had been reported that in severe COPD patients, uncontrolled oxygen administration could lead to hypercapnia [15]; therefore, physicians may have considered this when prescribing the flow rate.

All 30 physicians verified hypoxemia using pulse oximetry, and approximately 87% of physicians also performed arterial blood gas analysis when prescribing oxygen. According to the British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines [6], non-invasive monitoring is performed by the portable equipment used to start oxygen therapy. However, this modality may be inaccurate [16]. According to Carone et al. [17], non-invasive monitoring of oxygen saturation is inadequate for assessing arterial saturation in patients with COPD, and, when prescribing oxygen therapy, pulse oximetry should be used with a cut off limit imposed.

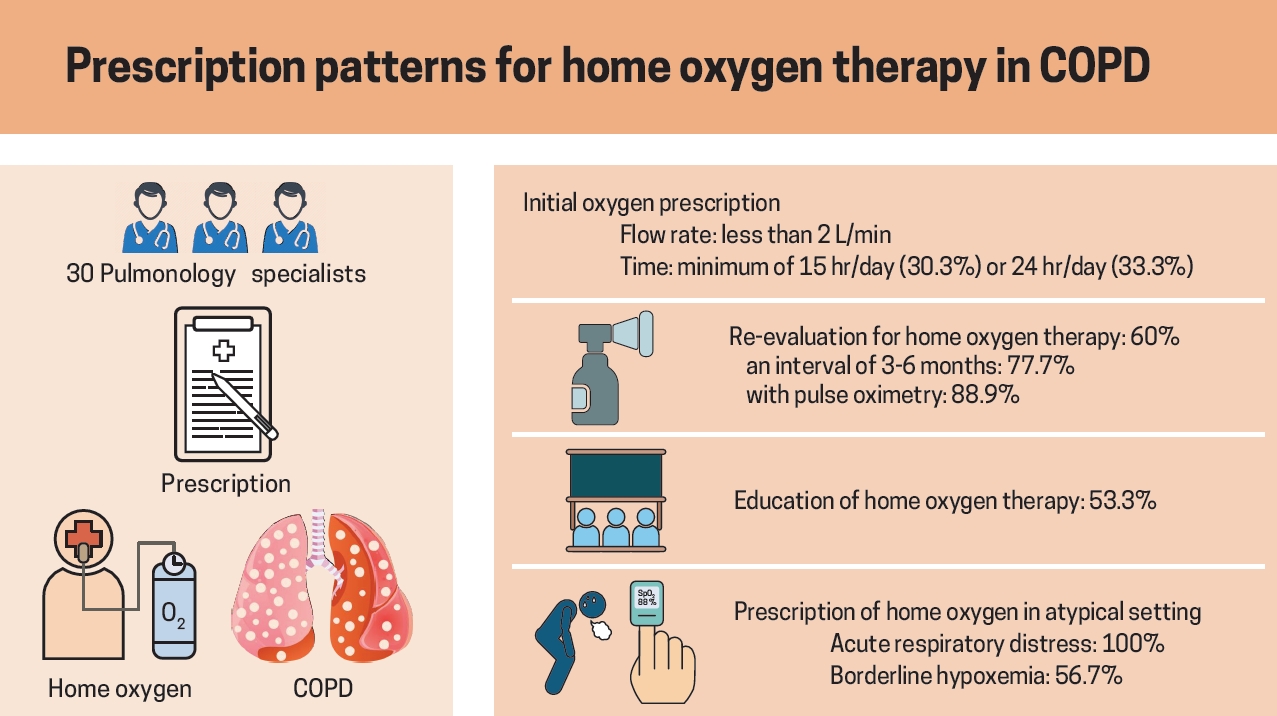

Inadequate understating of home oxygen therapy contributes to its underuse or misuse. Therefore, patient education, such as regular follow-ups, patient-provider communication, or well-organized programs, would help improve the outcome of home oxygen therapy [6,18]. In our study, about 50% of the physicians provided education about home oxygen therapy using the leaflets from home oxygen therapy service providers. The main reasons for not providing patient education were that physicians felt they did not have adequate time during outpatient clinics consultations and because the national insurance system does not cover the educational program. Almost all physicians (n = 29, 96.7%) were willing to provide an educational program if the health insured covered the program. Furthermore, they think that the physician in charge (n = 8, 26.7%), the nurses in outpatient clinics (n = 11, 36.7%), or the home visiting nurses (n = 8, 26.7%) should play a leading role in patient education (Fig. 3).

A total of 18 physicians (60.0%) re-evaluated the necessity of home oxygen therapy within 1 year, and the majority were re-evaluated within 3 to 6 months. Those who did not re-evaluate also responded that they did not have enough time during outpatient clinics consultations (n = 8, 66.7%). According to the previous studies on the re-evaluation of continuous oxygen therapy [19,20], there was no notable difference in the follow-up period; furthermore, a meaningful number of the patients prescribed home oxygen could discontinue the home oxygen therapy after appropriate re-evaluation. Therefore, not merely asking a “yes or no” question for determining patient compliance, the physicians should re-assess the need for adequate oxygen treatment.

Our study also surveyed the prescription experiences regarding borderline hypoxemia or post-discharge home oxygen treatment of acute respiratory distress. Seventeen physicians responded that they prescribe oxygen to patients with 92% to 93% saturation, but they limited the oxygen use to periods of exercise or dyspnea. However, a randomized study regarding home oxygen prescription to borderline hypoxemia patients indicated, there was no increase in long-term survival [10]. A meta-analysis reported that continuous oxygen could relieve dyspnea in mild or non-hypoxemic COPD patients [21].

Several cross-over studies have suggested that short-term oxygen therapy may improve the physiological variables during a short interval [22]; however, these benefits were not demonstrated in a relatively longer clinical trial [23]. In our survey, all the respiratory physicians confirmed that they prescribed home oxygen therapy to patients discharged after hospitalization due to dyspnea. In this case, the doctors restricted the home oxygen to special conditions, such as sleep, exercise, or periods of dyspnea. Additionally, 19 physicians re-evaluated home oxygen therapy within 6 months. Short-term oxygen therapy was occasionally used to relieve acute dyspnea without hypoxemia or in patients with borderline hypoxemia, despite weak evidence to support its effectiveness in this setting [6]. However, a real-world study about the effectiveness of short-term oxygen therapy during an acute respiratory distressed state at discharge or borderline hypoxemia would be needed.

This study was conducted on pulmonary specialists who agreed voluntarily to answer the questionnaire. Therefore, the number of participants (n = 30) was small. Although the involvement of respiratory physicians may be a confounding factor in interpreting the results of the questionnaire, the permitted license of a physician to issue the home oxygen prescription was also limited. Notably, however, the participants have been involved with COPD research in Korea [12], and we think this study sufficiently reflects the current state of oxygen prescription by pulmonary specialists in Korea. In addition, while previous studies on home oxygen therapy that focused on the patients’ perspective, this study has strength in that a questionnaire survey was completed by respiratory physicians who issued home oxygen prescriptions to assess physicians’ prescription patterns.

In this study, we demonstrated the prescription pattern of home oxygen therapy in Korea. Physicians issued oxygen prescription to patients with hypoxemic COPD for a minimum of 15 hours/day at a flow rate of less than 2 L/min. Home oxygen was also prescribed for patients at borderline hypoxemia or for relieving acute dyspnea symptoms at discharge. As patient education was not properly performed, physicians in Korea have recommended that a national policy be developed to improve the quality of home oxygen therapy, including a patient education program.

1. From this study, we investigated the real-world situation of physician oxygen prescription patterns in Korea.

2. Physicians issued oxygen prescription to patients with hypoxemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for a minimum of 15 hr/day at a flow rate of less than 2 L/min.

3. To overcome inadequate patient education performance, physicians in Korea have requested a national policy to improve the quality of home oxygen therapy, including an educational program for patients with COPD.

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and study code was 2015-E330011-00.

Table 1

Evaluation tools and numbers of trials when issuing oxygen prescriptions

| Tests | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Pulse oximetry | 30 (100) |

| Once | 11 (36.7) |

| Twice | 14 (46.7) |

| Three times | 3 (10.0) |

| Etc.a | 2 (6.6) |

| Arterial blood gas analysis | 26 (86.7) |

| Once | 17 (65.4) |

| Twice | 4 (15.4) |

| Three times | 3 (11.5) |

| Etc.b | 2 (7.7) |

| Six-minute-walk test | 3 (10.0) |

| Pulmonary function test | 2 (6.6) |

Table 2

Oxygen prescription in specific conditions

| Variable | Patients with hypoxemiaa | Patients with borderline hypoxemiab |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen use restriction (yes) | 13 (43.3) | 17 (56.7) |

| When to restrict oxygen use? | ||

| During sleep | 4 (30.8) | |

| During exercise | 6 (46.1) | 13 (76.5) |

| Use only for dyspnea | 1 (7.7) | 4 (23.5) |

| High dose at exercise and low dose as usual | 1 (7.7) | |

| No response | 1 (7.7) | |

| In exercise | ||

| Same as usual | 22 (73.3) | 10 (58.8) |

| Through 6-minutes-walk test | 4 (13.3) | 7 (41.2) |

| Etc.c | 4 (13.3) | |

| During sleep | ||

| Same as usual | 19 (63.3) | 11 (64.7) |

| More than at rest | 3 (10.0) | 3 (17.6) |

| With reference to previous night saturation | 7 (23.3) | 2 (11.8) |

| Less than at rest | 1 (3.3) | |

| No prescription | 1 (5.9) | |

a Hypoxemia was defined as an the arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) of at least 55 mmHg or oxygen saturation below 88%, or if PaO2 is between 55 and 60 mmHg or oxygen saturation is 89%, with pulmonary hypertension, peripheral edema from congestive heart failure, or erythrocytosis (hematocrit > 55%).

Table 3

Education about home oxygen therapy and available materials

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Education about home oxygen therapy (yes) | 16 (53.3) |

| Available education materials (yes)a | 8 (50.0) |

| Leaflets from service providers of home oxygen therapy | 8 (100.0) |

| Self-made educational materials | 1 (12.5) |

| Education about home oxygen therapy (No) | 14 (46.7) |

| Reasons for not doing education a | |

| Do not have time during outpatient clinic consultations | 13 (43.3) |

| Have no one to educate | 8 (26.7) |

| Do not have education materials | 8 (26.7) |

| No response | 1 (3.3) |

Table 4

Re-evaluation of home oxygen therapy

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Re-evaluation for home oxygen therapy (yes) | 18 (60.0) |

| Re-evaluation interval, mo | |

| 1 | 1 (3.3) |

| 3 | 8 (44.4) |

| 6 | 6 (33.3) |

| 12 | 3 (16.7) |

| Re-evaluation test a | |

| Pulse oximetry | 16 (88.9) |

| Arterial blood gas analysis | 10 (55.6) |

| Six-minutes-walk test | 1 (5.6) |

| Questionnaire (e.g., CAT) | 2 (11.1) |

| Pulmonary function test | 2 (11.1) |

REFERENCES

1. Yoon HK, Park YB, Rhee CK, Lee JH, Oh YM. Committee of the Korean COPD Guideline 2014. Summary of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease clinical practice guideline revised in 2014 by the Korean Academy of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Disease. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2017;80:230–240.

2. Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532–555.

3. Kent BD, Mitchell PD, McNicholas WT. Hypoxemia in patients with COPD: cause, effects, and disease progression. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011;6:199–208.

4. Kim V, Benditt JO, Wise RA, Sharafkhaneh A. Oxygen therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:513–518.

5. Gulbas G, Gunen H, In E, Kilic T. Long-term follow-up of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients on long-term oxygen treatment. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:152–157.

6. Hardinge M, Annandale J, Bourne S, et al. British Thoracic Society guidelines for home oxygen use in adults. Thorax 2015;70(Suppl 1):i1–i43.

7. Nocturnal Oxygen Therapy Trial Group. Continuous or nocturnal oxygen therapy in hypoxemic chronic obstructive lung disease: a clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 1980;93:391–398.

9. Lee KH. Home oxygen therapy in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Korean J Med 2007;73:353–360.

10. Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial Research Group. Albert RK, Au DH, et al. A randomized trial of long-term oxygen for COPD with moderate desaturation. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1617–1627.

11. Wijkstra PJ, Guyatt GH, Ambrosino N, et al. International approaches to the prescription of long-term oxygen therapy. Eur Respir J 2001;18:909–913.

12. Lee JY, Chon GR, Rhee CK, et al. Characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at the first visit to a pulmonary medical center in Korea: the KOrea COpd Subgroup Study Team Cohort. J Korean Med Sci 2016;31:553–560.

13. Shapiro BA, Peruzzi WT, Templin R. Normal ranges and interpretive guidelines. In: Shapriro BA, Peruzzi WT, eds. Clinical Application of Blood Gases. 5th ed.. St Louis (MO): Mosby-Year Book, 1994;57–67.

14. Long term domiciliary oxygen therapy in chronic hypoxic cor pulmonale complicating chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Report of the Medical Research Council Working Party. Lancet 1981;1:681–686.

16. Eaton T, Rudkin S, Garrett JE. The clinical utility of arterialized earlobe capillary blood in the assessment of patients for long-term oxygen therapy. Respir Med 2001;95:655–660.

17. Carone M, Patessio A, Appendini L, et al. Comparison of invasive and noninvasive saturation monitoring in prescribing oxygen during exercise in COPD patients. Eur Respir J 1997;10:446–451.

18. Peckham DG, McGibbon K, Tonkinson J, Plimbley G, Pantin C. Improvement in patient compliance with long-term oxygen therapy following formal assessment with training. Respir Med 1998;92:1203–1206.

19. Cottrell JJ, Openbrier D, Lave JR, Paul C, Garland JL. Home oxygen therapy: a comparison of 2- vs 6-month patient reevaluation. Chest 1995;107:358–361.

20. Oba Y, Salzman GA, Willsie SK. Reevaluation of continuous oxygen therapy after initial prescription in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care 2000;45:401–406.

21. Uronis HE, Ekstrom MP, Currow DC, McCrory DC, Samsa GP, Abernethy AP. Oxygen for relief of dyspnoea in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who would not qualify for home oxygen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2015;70:492–494.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Role of phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease2020 March;35(2)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement 1

Supplement 1 Print

Print