|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 39(3); 2024 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background/Aims

Since the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, hospitals have implemented infection control measures to minimize the spread of the virus within facilities. This study aimed to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on the incidence of healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs) and common respiratory virus (cRV) infections in hematology units.

Methods

This retrospective study included all patients hospitalized in Catholic Hematology Hospital between 2019 and 2020. Patients infected with vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE), Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), and cRV were analyzed. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) methods and interrupted time series analyses were performed to compare the incidence rates before and after the pandemic.

Results

The incidence rates of CPE and VRE did not differ between the two periods. However, the incidence of CDI increased significantly (IRR: 1.41 [p = 0.002]) after the COVID-19 pandemic. The incidence of cRV infection decreased by 76% after the COVID-19 outbreak (IRR: 0.240 [p < 0.001]). The incidence of adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, and rhinovirus infection significantly decreased in the COVID-19 period (IRRs: 0.087 [p = 0.003], 0.031 [p < 0.001], and 0.149 [p < 0.001], respectively).

Conclusions

The implementation of COVID-19 infection control measures reduced the incidence of cRV infection. However, CDI increased significantly and incidence rates of CPE and VRE remained unchanged in hematological patients after the pandemic. Infection control measures suitable for each type of HCAI, such as stringent hand washing for CDI and enough isolation capacities, should be implemented and maintained in future pandemics, especially in immunocompromised patients.

The outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV)-2 infection in December 2019 has become a turning point in healthcare systems worldwide [1]. The rapid spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused a high burden on the healthcare system. To effectively manage the pandemic, governments have implemented social distancing and isolation measures to limit personal contact [2,3]. Each hospital also imposed additional infection control measures, such as mandatory wearing of face masks, restriction of visitors, and limiting the number of caregivers to a single person to prevent the possible inflow of the new virus and minimize further transmission within the facility [4].

Patients who were admitted to hematology wards required additional attention because hematological malignancies necessitate aggressive chemotherapy and/or hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) causing profound immunosuppression. Such conditions make patients prone to healthcare-associated infections (HCAIs), which prolong hospitalization, increase medical expenditures, and sometimes result in mortality [5]. Whether precautions against COVID-19 positively or negatively affect the incidence of HCAIs remains unknown. Although some data suggest that limited personal contact and enhanced hygiene practices have reduced the incidence of HCAIs, others suggest that the redistribution of finite medical resources for COVID-19 prevention has led to inadequate HCAI control [6–9].

With regard to common respiratory virus (cRV) infections other than COVID-19, wearing face masks and prevention of droplet transmission reduce the risk of upper and lower respiratory tract infections [10]. However, changes in the incidence of HCAIs or cRV infections may differ depending on the characteristics of the virus, host factors, and hospital environmental factors.

The incidence rate of other infectious diseases after COVID-19 among hematological patients remains controversial. This study aimed to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of several major nosocomial pathogens, including carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE), vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE), Clostridium difficile, and cRVs, in hematological wards, to provide further insights for reinforcing infection control.

A retrospective review of the electronic medical records (EMRs) and clinical data warehouse (CDW) of all patients hospitalized at the Catholic Hematology Hospital of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital between January 2019 and December 2020 was conducted. Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital is a university-affiliated tertiary hospital with 1,365 beds. Catholic Hematology Hospital has 176 beds for hematological patients and performs over 500 HCT procedures annually. After the COVID-19 pandemic, strategies including screening questionnaires for patient classification, visitation restriction, temporary alternative medical services (screening clinics, separated respiratory clinics, telemedicine, etc.), pre-admission screening for COVID-19, and the operation of buffer rooms were implemented as part of the prevention strategy (Table 1). To assess for post-COVID-19 changes, 2019 was set as the control period, while 2020 was set as the COVID-19 period. To ensure the homogeneity of the study setting and avoid possible confounding factors, infectious diseases that occurred during hospitalization in wards outside the hematology unit were excluded from the analysis, even in patients with hematological diseases.

During the study period, rectal surveillance was performed for the detection of CPE in high-risk patients, patients with a history of CPE colonization or infection within 3 months, patients with recent hospitalization (≥ 1 wk) in other healthcare facilities within 4 weeks, exposed patients without contact precaution to confirmed CPE carriers, or patients who required admission to the intensive care unit. Rectal VRE surveillance was not performed during the study period. In cases where CPE was identified, the patient was isolated in a single-room with contact precautions until three consecutive negative results were obtained at one-week intervals. Additionally, rectal swabs were conducted on other patients sharing the same room. For patients confirmed to have VRE in clinical specimens, contact precautions were implemented. Infection control measures for both CPE and VRE remained unchanged throughout the study period.

A stool examination for the detection of C. difficile and multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the detection of cRV were performed in patients according to their symptoms, as standard patient care. Single-room isolation with contact precautions was implemented for patients with CDI. When a hospitalized patient presented new respiratory symptoms, a nasopharyngeal swab for cRV PCR was performed. In cases where lower respiratory tract symptoms or lung shadow were confirmed, bronchoscopy and cRV PCR of bronchial washing fluid were conducted. Droplet precautions were applied until the results became available, and monitoring of contacted patients was maintained.

Patients who tested positive for CPE or VRE on culture tests were diagnosed according to the microbiological results of the submitted specimen, regardless of the colonization and/or infection status. The clinical isolates were subjected to routine species identification and susceptibility testing using automated systems. To identify the presence of rectal CPE, a carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales (CRE) test was performed, which included selective CRE culture and carbapenemase gene testing for blaIMP1, blaVIM, blaNDM, blaKPC, and blaOXA48 using the Xpert Carba-R assay (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Rectal swabs were collected using an eSwab 480CE collection system (Copan Diagnostics Inc., Brescia, Italy) [11]. VRE was defined as Enterococci isolated from clinical specimens that are resistant to vancomycin or express the vanA or vanB genes [12]. C. difficile infection (CDI) was defined according to the standard epidemiological classification [13]. Stool samples that did not meet the conditions for C. difficile testing were rejected by the microbiological laboratory of our hospital. cRV pathogens were counted based on the multiplex real-time PCR results. To ensure that only HCAI patients admitted to the hospital were selected, those who obtained positive test results within 48 hours of hospitalization were excluded from the analysis.

The following data were collected from the EMR and CDW: data on the number of positive results on CPE, VRE, C. difficile, and multiplex RV-PCR panel tests (influenza virus A/B; respiratory syncytial virus [RSV] A/B; parainfluenza virus 1, 2, and 3; adenovirus; metapneumovirus; rhinovirus A, B, and C; coronavirus [229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43]; and bocavirus) and influenza A/B rapid antigen tests. The microbiological results were collected as part of the routine care for hematology patients. If CPE or VRE was repeatedly detected in the same patient, the occurrence of the same infection within 30 days was considered as the same episode. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (KC21RISI0282 and KC21WISI0258). Written informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board.

Chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, while Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous variables. The HCAI incidence rates were compared using the incidence rate ratio (IRR) method. The incidence density was calculated as the number of positive cases per 1,000 patient-days. To compare the rates per patient per day, the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. Interrupted time series analysis was used to evaluate the outcomes with time trends. The autoregressive integrated moving average model was used to investigate the effect of COVID intervention on the incidence of HCAI. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R studio version 4.3.1.

The median number of patients admitted to this hematology hospital was 310.5 (range, 257–343) per month during the study period; a median of 324 patients was hospitalized per month in 2019 and a median of 297 patients per month in 2020 (p = 0.002). The median length of hospital stay was 18.8 days (range, 15.1–22.2): 17.1 days in 2019 and 19.2 days in 2020 (p < 0.001). The median patient-days were 21.44 per month in 2019 and 22.13 per month in 2020, which showed no significant differences (p = 0.198)

During the 2-year study period, 31 microbiologically confirmed CPE cases were identified in 24 patients with hematological diseases. Excluding the number of repeated detections in the same patient according to our definition, the incidence rates of CPE were 0.134/1,000 patient-days (n = 11) and 0.166/1,000 patient-days (n = 13) in the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods. The IRR (95% CI) was 1.24 (0.557–2.777) (p = 0.593) for CPE. The incidence rates of VRE including newly diagnosed events were 1.576/1,000 patient-days (n = 126) and 1.493/1,000 patient-days (n = 117) during the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods, respectively, of which the IRR (95% CI) was 0.95 (0.736–1.218) (p = 0.905). CDI developed in 149 and 197 patients during the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods, respectively, and the incidence rate increased from 1.866/1,000 patient-days in 2019 to 2.630/1,000 patient-days in 2020. The IRR (95% CI) was 1.41 (1.140–1.744) (p = 0.001) for CDI (Table 2).

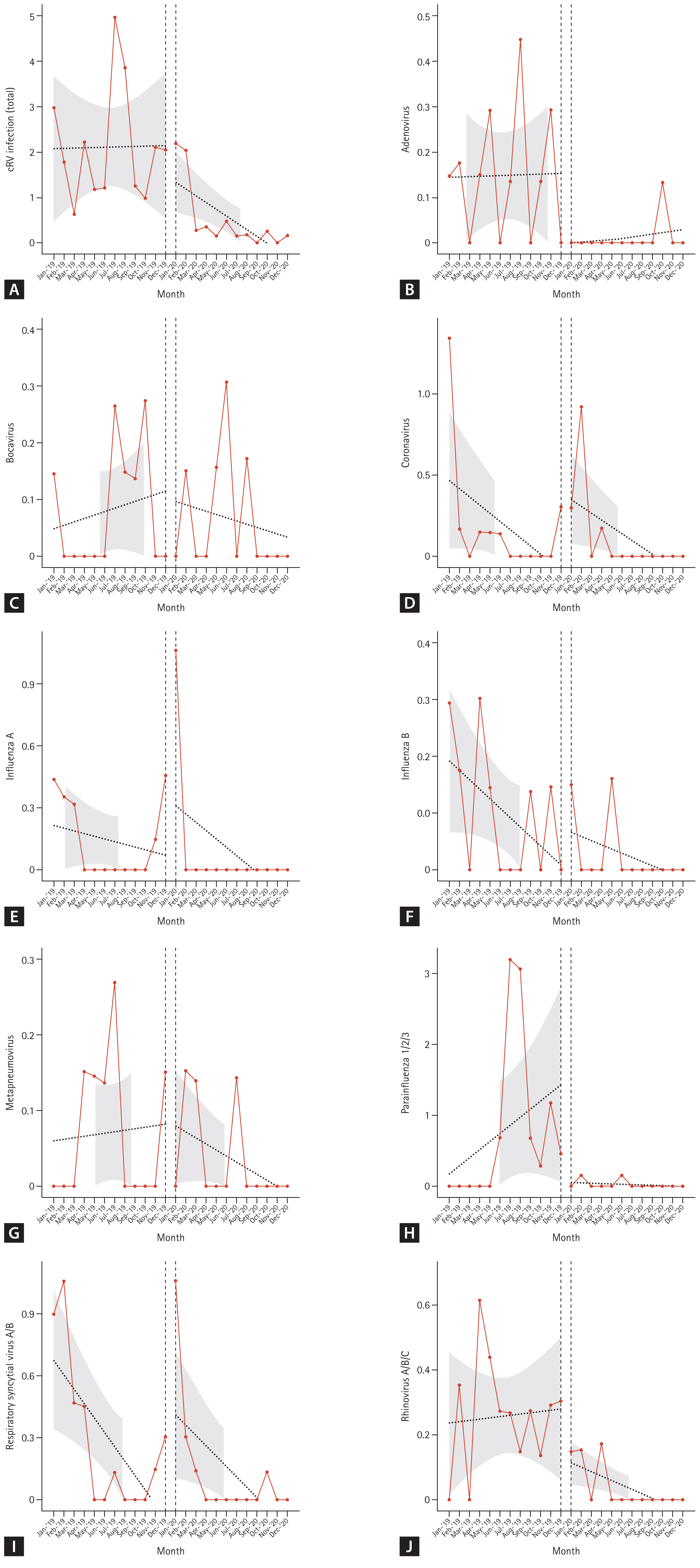

An interrupted time series analysis was performed, and the results showed no statistical significance in the slope and change in the intercept for CPE and VRE. However, for the CDI, the change in the intercept showed a significant increase in the post-COVID-19 period (change in intercept coefficient: 1.264; p = 0.044) (Table 3, Fig. 1). However, the slope of CDI incidence showed similar trends in 2019 and 2020.

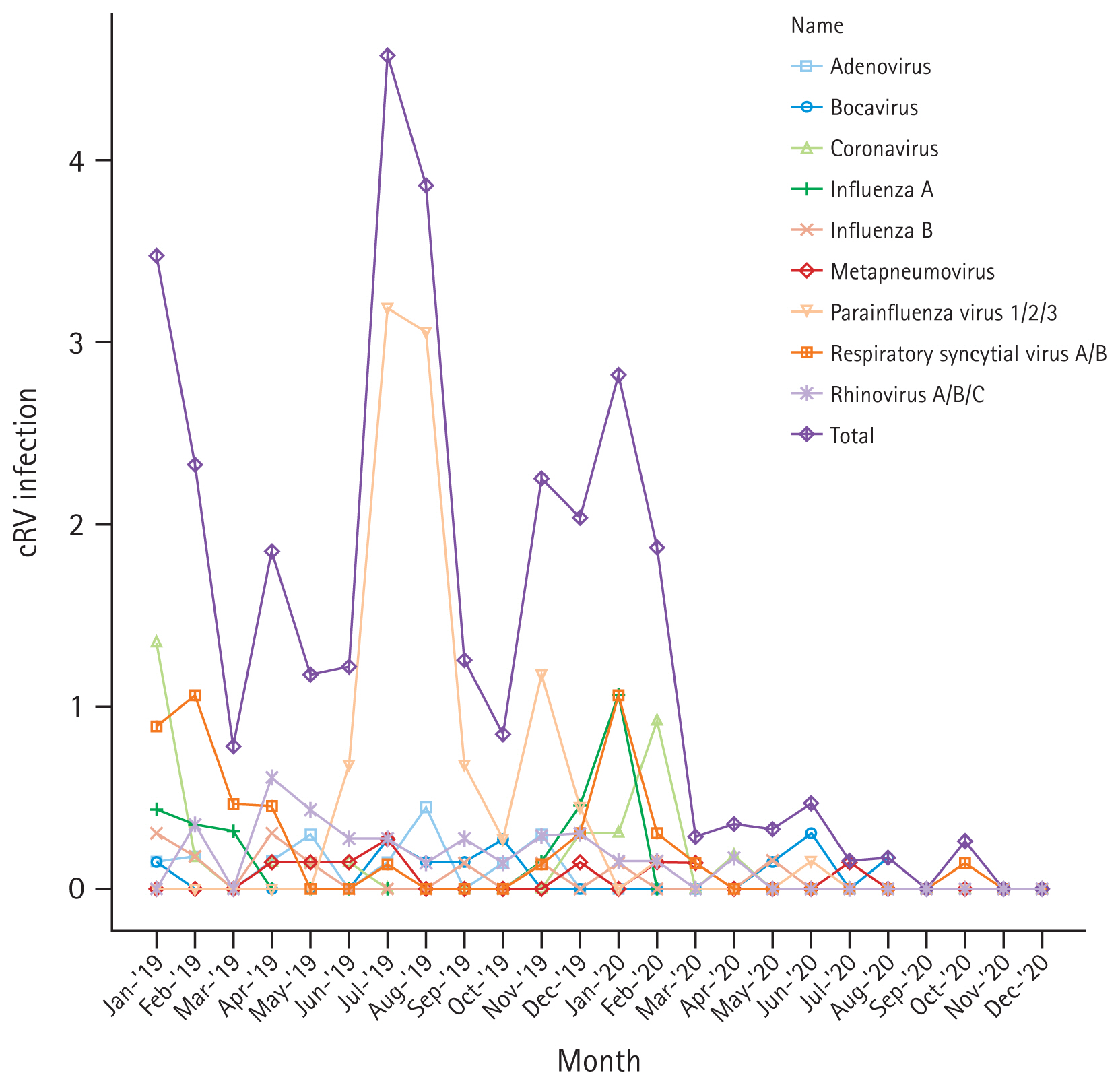

A total of 205 adult patients with HCAI from six hematology units tested positive for cRV on PCR. Among all cRV cases, parainfluenza virus was the most prevalent virus, followed by RSV and rhinovirus. Notably, as shown in Figure 2, traditional seasonal variations were changed in post-COVID-19 period as well as the incidence of cRV infections. The cumulative incidence density rates of PCR-proven cRV during the control and COVID-19 periods were 2.167 cases per 1,000 patient-days (n = 165) and 0.519 cases per 1,000 patient-days (n = 40), respectively. The detection rate of cRV declined by 76% (IRR: 0.240, 95% CI: 0.170–0.339, p < 0.001) in the COVID-19 period compared with that in the control period (Table 4).

Although the total cRV detection rate decreased, the incidence of each type of virus differed; the incidence of adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, and rhinovirus infection showed a significant decrease in the COVID-19 period compared with that in the control period (IRRs: 0.087 (p = 0.003), 0.031 (p < 0.001), and 0.149 (p < 0.001), respectively). However, no significant differences were observed in the IRRs for bocavirus, coronavirus, enterovirus, influenza virus A, influenza virus B, metapneumovirus, or RSV (Table 4). Figure 3 shows the detailed incidence of nosocomial cRV infections per month. Figure 3 and Table 5 show the results of the interrupted time series analysis for all and each type of cRV, respectively.

In this study, the trends in the incidence rates of CPE, VRE, CDI, and cRV infections in the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods were investigated. An increased incidence of CDI was observed after the COVID-19 pandemic, while no significant changes were observed in the incidence rates of CPE and VRE infection in hematological patients. Additionally, a decreased incidence of cRV infection was confirmed, the statistical significance of which varied according to the type of viruses.

In the case of HCAI caused by CPE and VRE, although enhanced hand hygiene practices and restrictions on the number of visitors or guardians were strictly implemented in hematology hospitals, our additional measures did not lead to a significant change. As CRE infection is regarded as a notifiable infectious disease in South Korea, the incidence of CRE, regardless of the carbapenemase production, has increased from 15,369 cases in 2019 to 18,113 cases in 2020, according to the national data from the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency [14]. Data from other countries also reported significant increases in HCAI during the early phase of an emergency due to the limitations of traditional HCAI prevention and control efforts [15–18]. We also experienced shortages in the workforce of healthcare personnel and rooms for isolation. However, our results showed no significant differences, without an increase in either the intercept change or slope for CPE and VRE (Fig. 1).

Although antibiotics do not have antiviral effects, their use has increased after the COVID-19 pandemic [19–21]. A systematic review of the COVID-19 pandemic and antibiotic consumption suggested that the interruption of antibiotic stewardship programs during the pandemic also resulted in an increase in antibiotic use among hospitalized patients [22]. However, the overall consumption of antibiotics (either intravenously or orally) did not increase in Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital; the defined daily dose of intravenous antibiotics used decreased from 618.9/1,000 hospital-days in 2019 to 609.5/1,000 hospital-days in 2020, while that of oral antibiotics used decreased from 395.7/1,000 persons to 357.5/1,000 in 2020. This could be one of the possible explanations for the insignificant changes in the incidence rates of CPE and VRE infection in our institution, despite the nationwide increasing incidence of CRE infection.

The increasing incidence of CDI was proven by both IRR comparison and interrupted time series analysis in this study. However, the impact of COVID-19 on the incidence of CDI remains controversial. A report from the National Healthcare Safety Network did not demonstrate a significant increase in CDI in the United States [23]. However, our results are in line with those of a long-term study in Italy, which showed an increasing trend in CDI incidence [24]. These results can be attributed to the fact that the use of alcohol-based hand rubs does not prevent CDI transmission, which requires strict adherence to the practice of hand washing with soap and water. Additionally, a single-room isolation of patients with CDI was not a priority during the COVID-19 pandemic in most hospitals in Korea. Although the overall antibiotics consumption of the hospital has not increased between 2019 and 2020, it is necessary to calculate the defined daily dose (DDD) of hematology hospital to elucidate the relationship between the occurrence of CDI and antibiotics usage. The DDD of the hematology hospital could not be calculated separately during the study period, but the consumption of major antibiotics including cefepime, imipenem, or teicoplanin was not increased (data not shown). The multifactorial nature of CDI development, such as the interactions between bacterial and viral infections, acid-suppressive medications, gut microbiota in patients susceptible to mucosal barrier injury, antimicrobial stewardship, environmental cleaning, and isolation capacity, should be considered in future studies [25].

Our results revealed a significant decrease in cRV infections, which is consistent with previous studies conducted in hematology patients in the United Kingdom [10]. This also reflects the reduced detection rates of respiratory viruses in the general population [26–28]. These results may confirm the unintended benefits of COVID-19 prevention measures, as the majority of respiratory pathogens are transmitted through droplets. The enhanced hygiene practices and the mandatory use of face mask are believed to be responsible [29]. As shown in Figure 2, the incidence of cRV infection has remained relatively steady during the immediate post-COVID-19 period (January–February 2020). This is thought to be partly attributed to the lingering impact of the epidemiology from the pre-COVID-19 period. The incidence of infection of each type of respiratory virus in the hematology units generally mirrors the seasonal trends and variability of community infections in Korea [30]. In this context, it is difficult to conclude that the decrease in cRV infection rates observed in this study is solely attributable to changes in in-hospital infection control measure before and after COVID-19. The discrepancy between IRR and interrupted time series analysis results for cRV infection in this study might stem from the combined effect of monthly variations or characteristics of the virus itself such as droplet size, transmission, etc. Further studies, conducted over an extended period after COVID-19, are necessary to assess the anticipated seasonal changes and determine whether the reduced incidence of cRV infections persists.

This study has several limitations. The study was conducted in a single institution within a short term. Therefore, long-term studies involving multiple institutions are required to draw clear conclusions. In addition, it was not possible to confirm whether the infection control policies were implemented properly because this was not a study conducted in a controlled situation owing to the nature of retrospective research using medical records. The changes in other medical risk factors, such as patient demographics and severity, should be considered as well.

In conclusion, the implementation of COVID-19 infection control measures led to a notable reduction in the number of cRV infections. However, the incidence of CDI significantly increased as the intercept coefficient changed in hematological patients after the COVID-19 pandemic. The incidence rates of CPE and VRE remained unchanged. Infection control measures suitable for each HCAI, not only contact and droplet precautions, but also single-room isolation capacities or monitoring of antibiotic consumption, are warranted to maintain sustainable measures to prevent HCAI in future pandemics.

1. The number of cRV infections decreased after COVID-19 pandemic due to infection control measures.

2. C. difficle infection increased significantly, while CPE and VRE infections remained steady.

3. To ensure the effectiveness of infection control strategies against various HCAIs, not only contact and droplet precautions but also single-room isolation and monitoring of antibiotic usage are essential.

Acknowledgments

Statistical consultation was supported by the Department of Biostatistics of the Catholic Research Coordinating Center.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Seohee Oh: conceptualization, resources, investigation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing; Yu-Sun Sung: conceptualization, resources, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft; Mihee Jang: conceptualization, resources, investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft; Yong-Jin Kim: conceptualization, resources, investigation, data curation, formal analysis; Hyun-Wook Park: conceptualization, resources, investigation, data curation, formal analysis; Dukhee Nho: writing - review & editing; Dong-Gun Lee: writing - review & editing; Hyeon Woo Yim: writing - review & editing; Sung-Yeon Cho: conceptualization, resources, investigation, formal analysis, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing

Figure 1

Trends in incidence rate (/1,000 hospital-day) of CPE (A), VRE (B), and Clostridium difficile infection (C) before after the COVID-19. CPE, carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales; VRE, vancomycin-resistant Enterococci.

Figure 2

Monthly incidence rate (/1,000 hospital-day) of each cRV during 2019–2020. cRV, common respiratory virus.

Figure 3

Trends in incidence rate (/1,000 hospital-day) of total cRV (A), adenovirus (B), bocavirus (C), coronavirus (D), influenza A (E), influenza B (F), metapneumovirus (G), parainfluenza 1/2/3 (H), RSV A/B (I), rhinovirus A/B/C (J) before and after the COVID-19. cRV, common respiratory virus; RSV, respiratory syncytial virus.

Table 1

Major changes in infection control policies in Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital after the COVID-19 pandemic

| January, 2020 | Mandatory mask-wearing, complete visitation restrictions, closure of the north/east entrances, inquiry into the travel history of inpatients/guardians, and commencement of operation for reassurance clinicsa) |

| February, 2020 | Strengthening the admission process (pre-admission COVID-19 PCR for patients and bedside caregiver), Re-defining the target population for screening clinics and reassurance clinics, restriction on the number of guardians |

| March, 2020 | Buffer rooms operation |

| May, 2020 | Restriction of inpatient movement (restriction on leaving outside the ward, excluding essential tests |

| September, 2020 | Notification of reimbursement for pre-admission COVID-19 PCR testing |

Table 2

Comparison of incidence of major healthcare associated pathogens during the pre- and post-COVID-19 period in hematologic unit

Table 3

Interrupted time series regression analysis of monthly cases by pathogen

Table 4

Incidence rate and incidence rate ratio of PCR-proven common respiratory virus in pre- and post-COVID-19 period

Table 5

Interrupted time series regression analysis of monthly common respiratory virus infections

REFERENCES

1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727–733.

2. Lai S, Ruktanonchai NW, Zhou L, et al. Effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions to contain COVID-19 in China. Nature 2020;585:410–413.

3. COVID-19 National Emergency Response Center, Epidemiology & Case Management Team, Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Contact transmission of COVID-19 in South Korea: novel investigation techniques for tracing contacts. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 2020;11:60–63.

4. Cho SY, Park SS, Lee JY, et al. Successful prevention and screening strategies for COVID-19: focus on patients with haematologic diseases. Br J Haematol 2020;190:e33–e37.

5. Stevens MP, Doll M, Pryor R, Godbout E, Cooper K, Bearman G. Impact of COVID-19 on traditional healthcare-associated infection prevention efforts. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020;41:946–947.

6. Hu LQ, Wang J, Huang A, Wang D, Wang J. COVID-19 and improved prevention of hospital-acquired infection. Br J Anaesth 2020;125:e318–e319.

7. Wee LEI, Conceicao EP, Tan JY, et al. Unintended consequences of infection prevention and control measures during COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Infect Control 2021;49:469–477.

8. Cerulli Irelli E, Orlando B, Cocchi E, et al. The potential impact of enhanced hygienic measures during the COVID-19 outbreak on hospital-acquired infections: a pragmatic study in neurological units. J Neurol Sci 2020;418:117111.

9. Baccolini V, Migliara G, Isonne C, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare-associated infections in intensive care unit patients: a retrospective cohort study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2021;10:87.

10. Eyre TA, Peters L, Andersson MI, Peniket A, Eyre DW. Reduction in incidence of non-COVID-19 respiratory virus infection amongst haematology inpatients following UK social distancing measures. Br J Haematol 2021;195:194–197.

11. Yoo IY, Shin DP, Heo W, Ha SI, Cha YJ, Park YJ. Comparison of BD MAX Check-Points CPO assay with Cepheid Xpert Carba-R assay for the detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae directly from rectal swabs. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2022;103:115716.

12. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Case definitions for national notifiable infectious diseases [Internet] Cheongju: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, 2023. [cited 2023 Sep 1]. Availble from: https://npt.kdca.go.kr/pot/ii/sttyInftnsds/sttyInftnsds.do?icdCd=ND0501.

13. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:478–498quiz 499.

14. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Infectious diseases hompage [Internet] Cheongju: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, 2021. [cited 2023 Sep 1]. Availble from: https://npt.kdca.go.kr/pot/is/inftnsds.do.

15. Farfour E, Lecuru M, Dortet L, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales outbreak: another dark side of COVID-19. Am J Infect Control 2020;48:1533–1536.

16. Thomas GR, Corso A, Pasterán F, et al. Increased detection of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales bacteria in Latin America and the Caribbean during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emerg Infect Dis 2022;28:1–8.

17. Gomez-Simmonds A, Annavajhala MK, McConville TH, et al. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales causing secondary infections during the COVID-19 crisis at a New York City hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021;76:380–384.

18. Park SY, Cheong HS, Kwon KT, et al. Guidelines for infection control and burnout prevention in healthcare workers responding to COVID-19. Infect Chemother 2023;55:150–165.

19. Malik SS, Mundra S. Increasing consumption of antibiotics during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for patient health and emerging anti-microbial resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;12:45.

20. Jeon K, Jeong S, Lee N, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on antimicrobial consumption and spread of multidrug-resistance in bacterial infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11:535.

21. Meschiari M, Onorato L, Bacca E, et al. Long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on in-hospital antibiotic consumption and antibiotic resistance: a time series analysis (2015–2021). Antibiotics (Basel) 2022;11:826.

22. Fukushige M, Ngo NH, Lukmanto D, Fukuda S, Ohneda O. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on antibiotic consumption: a systematic review comparing 2019 and 2020 data. Front Public Health 2022;10:946077.

23. Weiner-Lastinger LM, Pattabiraman V, Konnor RY, et al. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on healthcare-associated infections in 2020: a summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2022;43:12–25.

24. Spigaglia P. Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaerobe 2022;74:102518.

25. Jeon YD, Ann HW, Lee WJ, et al. Characteristics of faecal microbiota in Korean patients with clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea. Infect Chemother 2019;51:365–375.

26. Kim MC, Kweon OJ, Lim YK, Choi SH, Chung JW, Lee MK. Impact of social distancing on the spread of common respiratory viruses during the coronavirus disease outbreak. PLoS One 2021;16:e0252963.

27. Lee H, Lee H, Song KH, et al. Impact of public health interventions on seasonal influenza activity during the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e132–e140.

28. Noh JY, Seong H, Yoon JG, Song JY, Cheong HJ, Kim WJ. Social distancing against COVID-19: implication for the control of influenza. J Korean Med Sci 2020;35:e182.

29. Suess T, Remschmidt C, Schink SB, et al. The role of facemasks and hand hygiene in the prevention of influenza transmission in households: results from a cluster randomised trial; Berlin, Germany, 2009–2011. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:26.

30. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Weekly Sentinel Surveillance Report. 2023 16th week (16 April–22 April). [Internet] Cheongju: Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, 2021. [cited 2023 Sep 1]. Availble from: https://npt.kdca.go.kr/pot/is/st/ari.do.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print