Extraskeletal Ewing's Sarcoma of the Head and Neck Presenting as Blindness

Article information

Abstract

Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma is rarely found in the head and neck regions. We report an unusual case of extraskeletal Ewing's Sarcoma of the parapharynx region in a 49-year-old man who presented with blindness. MRI examination showed marked enhancement of tumor thrombosis involving the superior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus, and internal jugular vein. The final diagnosis was extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma after biopsy of the internal jugular vein thrombosis by histopathological evaluation and immunohistochemical assay. In addition, the patient was diagnosed as having adenocarcinoma of the rectum by biopsy of the rectal mass. The patient was treated with systemic chemotherapy and showed improved response with durable remission. The patient's visual acuity, however, did not improve.

INTRODUCTION

Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma is a rare, round-cell, malignant tumor of uncharacterized mesenchymal cell origin that manifests most commonly in the paravertebral and intercostal regions. It occurs predominantly in adolescents and young adults between the ages of 10 and 30 years and it follows an aggressive course with a high rate of recurrence. Distant metastases are also common in extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma. It was first recognized by Tefft et al in 19691) when he reported four patients with paravertebral soft tissue tumors that histologically resembled Ewing's sarcoma. In 1975, Angervall and Enzinger2) reviewed 39 patients with malignant soft tissue paravertebral tumors not arising from bone but having similar morphologic characteristics to osseous Ewing's sarcoma. The head and neck region is an unusual primary site for this type of tumor and, according to Chao et al.3), there were only five out of 118 cases of extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma located in the head and neck region.

CASE REPORT

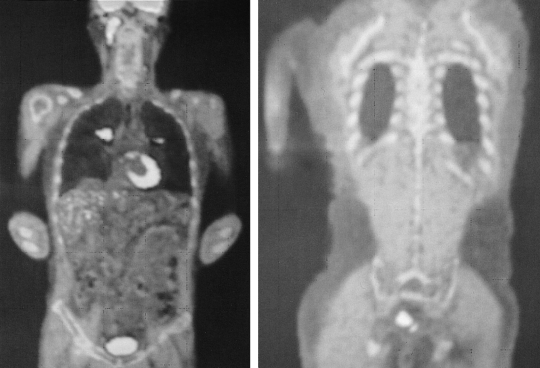

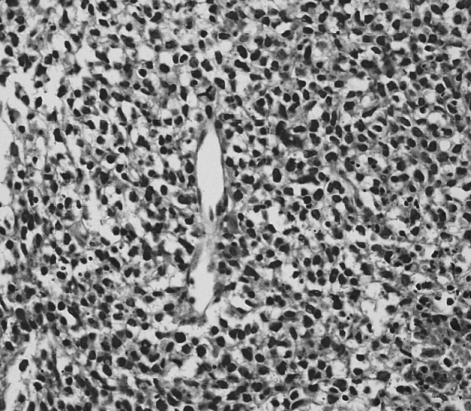

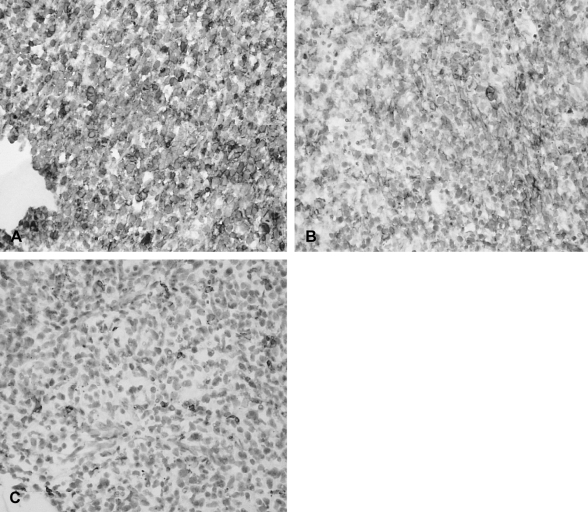

A 49-year-old man presented with a six-month history of diplopia and mild headache. The diplopia was gradually aggravated and blindness developed two months before he visited our hospital. Ophthalmologic examination revealed bilateral papilledema and atropy of the optic nerve. MRI examination showed marked enhancement of the tumor thrombosis involving the superior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus, and internal jugular vein (Figure 1). Additional PET-CT examination showed hypermetabolic lesion of the neck, mediastinal lymph node, lung and rectum in addition to lesions of the head and neck (Figure 2). The patient underwent a gun biopsy of the internal jugular vein thrombosis and a sigmoidoscopic biopsy of the rectal mass. Histopathological examination of the internal jugular vein thrombosis showed a small, round-cell malignant tumor with extensive geographic necrosis (Figure 3). Immunohistochemical studies showed that the tumor cells stained positive for CD99, Vimentin, and CD56, but stained negative for S-100, Desmin, Chromogranin, and leukocyte common antigen (Figure 4). Based on MRI and PET-CT findings, the histological pattern, and the results of the immunohistochemical studies, the final diagnosis was extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma of the parapharynx with pulmonary metastasis. Histopathological examination of an ulcerative rectal mass showed well- differentiated adenocarcinoma and, therefore, the patient was also diagnosed with rectal cancer (Figure 5). The patient was treated with palliative radiotherapy on the parapharynx and systemic chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, adriamycin and vincristine, after which Grade IV febrile neutropenia and Grade III diarrhea developed. He could not receive further treatment due to poor tolerance and the toxicity of the treatment. A follow-up examination with PET after 20 months showed that the hypermetabolic lesions of the head, neck and chest disappeared, but no significant interval change was observed in the hypermetabolic lesion of the rectum (Figure 6). The patient's visual acuity, however, did not improve.

Brain MRI. T-1 weighted image showed tumor thrombosis involving the superior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, transverse sinus, and sigmoid sinus.

Histopathology showed malignant, small, round cells with prominent nuclei but scanty cytoplasm (H&E stain, ×400).

Immunohistochemical studies showed that the tumor cells stained positive for CD99 (A) and CD56 (B), but stained negative for leukocyte common antigen (C) (×400).

Histopathology of ulcerative rectal mass reveals welldifferentiated adenocarcinoma (H&E stain, ×400).

DISCUSSION

The histological image of extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma is a small, blue, round cell with a scanty cytoplasm and it is often confused with other small round-cell tumors. Nearly all of the tumors within the Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors express the MIC2 gene product, CD99, on their cell membranes. Antibody staining for CD99 helps to confirm the diagnosis4). Lymphoblastic lymphoma and rhabdomyosarcoma can be excluded by negative staining for leukocyte common antigen, CD30, myosin, actin, and myoglobulin. Neuroblastoma can be excluded by negative staining for neurofilament, neuron-specific enolase, and the S-100 protein5, 6). Our patient was diagnosed with extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma based on the results of extensive immunohistochemical staining as described above.

Our patient's case of extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma developed in the parapharynx and resulted in gradual visual loss due to tumor thrombosis. The diagnosis of extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma was delayed in our patient because he was quite older than most patients with extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma. In addition, the patient's case of extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma was accompanied by rectal cancer. However, in comparison to the poor clinical outcome typically associated with extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma, this patient demonstrated durable remission after radiation and combination chemotherapy, but his visual acuity did not improve. Examination of the patient's eye revealed bilateral optic disc swelling (papilledema) and atropy of the optic nerve. The patient's visual loss might have been due to the tumor thrombosis involving the superior sagittal sinus, straight sinus, transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus, and internal jugular vein. Papilledema might have been caused by elevated intracrainal pressure due to the tumor thrombosis of the dural venous sinus. With unremitting papilledema, the maintenance of optic nerve atropy resulted in blurred vision. According to Peter et al7), when 77 patients with cerebral venous thrombosis were followed up for a mean of 77.8 months, two patients who initially presented with isolated intracranial hypertension had blindness due to optic atrophy. Our case serves as a good example of gradual visual loss due to extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma of the parapharynx. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma is a tumor sensitive to multimodality treatment. Early awareness and wide resection followed by chemotherapy and radiotherapy might improve the long-term survival of patients with extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma. The rate of survival in extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma has improved from 8% to nearly 65% in patients with extremity lesions and to 83% in patients with truncal lesions, and the prognosis is now approaching that of skeletal Ewing's tumors8). Further research is needed to improve the therapeutic strategy according to the proper clinical course.