Lymphocytic Interstitial Pneumonia in Primary Sjögren's Syndrome: A Case Report

Article information

Abstract

Sjögren's syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disorder in which lymphocytes infiltrate the exocrine glands, resulting in the development of sicca symptoms. Lymphocytes may also invade various other organs and cause diverse symptoms. Interstitial pneumonia has been observed frequently in SS patients. Typically, the pneumonia responds well to systemic steroids, and fatal cases are rare. We experienced a case of lymphocytic pneumonia accompanied by SS and treated with cyclophosphamide pulse therapy, and we present details of the case herein.

INTRODUCTION

Sjögren syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disease that is characterized by lymphocyte infiltration of exocrine glands, resulting in dryness of the mouth and eyes. In addition, other organs can be involved, including the joints, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and blood vessels, with concomitant diverse symptoms [1]. Interstitial pneumonia is frequently observed in patients with SS, who commonly present with a dry cough. Although the number of reported cases of SS and interstitial pneumonia is limited, it appears to respond well to systemic steroids [2]. Carrinon and Liebow first described lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP) [3]. This type of pneumonia is characterized by diffuse infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The cause of LIP is unclear. However, it has been associated with idiopathic or acquired human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Epstein-Barr virus infection, and autoimmune disorders [4]. LIP has also been associated with SS; 25% of LIP patients have been reported to have SS [5]. However, there is limited information on SS patients with LIP [6,7]. Here we describe a case of LIP with primary SS and treatment with cyclophosphamide pulse therapy.

CASE REPORT

A 29-year-old man visited a local clinic due to respiratory distress on mild exercise, accompanied by dry eyes and mouth. He was an office worker, and past medical and family histories were unremarkable. The patient was diagnosed with primary SS, and his chest computed tomography (CT) showed interstitial pneumonia in both lung fields. Oral administration of prednisolone and hydroxychloroquine with additional symptomatic therapy for sicca symptoms of the eyes and mouth were provided, but the patient's symptoms did not improve. Therefore, azathioprine and methotrexate were added to the treatment, but these medications were discontinued due to exacerbation of the symptoms. The patient was then referred to our hospital, and his vital signs were as follows: blood pressure 120/70 mmHg; pulse rate 78/min; respiration rate 20/min, and body temperature 36.7℃. The patient was conscious and oriented; he appeared chronically ill. There were corneal erosions noted on eye examination, a decrease in lacrimal secretions with the 5-mm Schirmer test, and xerostomia. Chest auscultation revealed crackles in both lung fields; the heart sounds were normal. The abdomen and extremities were unremarkable, and lymphadenopathy was not observed.

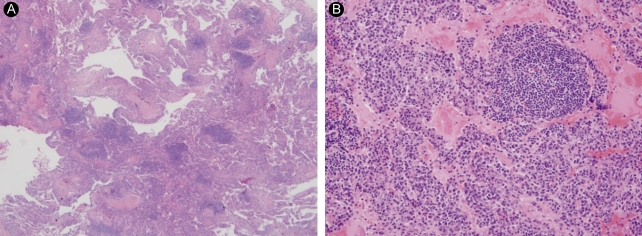

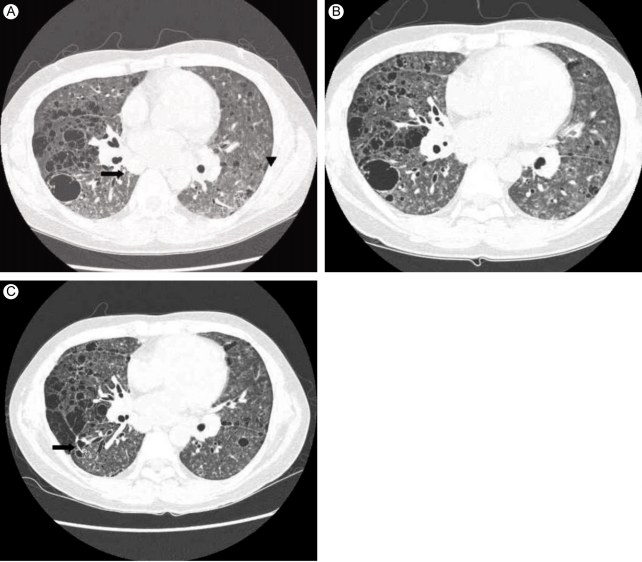

The results of laboratory studies showed a white blood cell count of 11,900/mm2 (neutrophil 86.5%), hemoglobin of 10.4 g/dL, and platelet count of 720,000/mm2. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and the C-reactive protein were elevated at 66 mm/hr and 124.2 mg/L, respectively. The serum biochemistry, including SGOT/SGPT, ALP, γ-GT, and LDH values, were 13/19 IU/L, 191 IU/L, 46 IU/L, and 252 IU/L, respectively (all within normal ranges). However, the total protein was elevated at 10.9 g/dL and the albumin was decreased at 2.5 g/dL. These findings indicated a reversal of the albumin to globulin ratio. In addition, the blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and other electrolyte test results, as well as the urine analysis, were all within normal limits. The rheumatoid factor was 26 IU/mL and the antinuclear antibody was 1:40 with positive speckles and anti-SSA antibodies. Immunoglobulins G, A, and M were all elevated at 6,224 mg/dL, 848 mg/dL, and 404 mg/dL, respectively. Protein electrophoresis of the serum did not show a monoclonal peak. Anti-SSB, anti-centromere, and anti-Jo-1 antibodies were all negative. The arterial blood gas had a pH of 7.469, pO2 of 73.4 mmHg, pCO2 of 35.5 mmHg, and an HCO3 of 25.2 mmol/L. The results of the pulmonary function and pulmonary diffusing capacity tests were consistent with moderate restrictive disorder. On transthoracic echocardiography, the systolic pressure of the pulmonary artery was normal at 22 mmHg, and the other findings were also within normal limits. A plain chest radiograph showed a diffuse interstitial shadow in both lung fields, and cysts of different sizes distributed superiorly with numerous areas of air in the upper and middle lung zones. Moreover, centrilobular nodules were observed in the lower lung zone, and extensive lymphadenopathy was seen in both the hilar and mediastinum regions (Fig. 1A). We diagnosed the patient with interstitial pneumonia associated with primary SS, and increased the prednisolone to 1 mg/kg/day after excluding the presence of infection.

(A) Lung window setting of thin-section computed tomography (CT) at the level of the aortic valve shows multiple, variable-sized, thin-walled cystic lesions throughout both lungs. Poorly-defined small nodules are seen mainly in both lower lobes (arrowheads). Subcarinal lymph node enlargement is also noted (arrow). (B) Thin-section CT taken 2 months after 1A shows slightly increased numbers of cysts and centrilobular nodules in both lungs. (C) Thin-section CT taken 6 months after 1B shows no significant interval change in the extent of cysts and nodules in either lung. Note postbiopsy scarring in the right lower lobe (arrow).

After 2 months, the symptoms did not worsen, and we gradually reduced the prednisolone to 0.5 mg/kg/day. However, the interstitial pneumonia progressed on the follow-up CT (Fig. 1B). LIP was diagnosed by lung biopsy (Fig. 2A and 2B) performed by video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) under general anesthesia. There was no evidence of malignancy in the biopsy specimen. We added cyclophosphamide pulse therapy (800 mg/mon, 500 mg/m2), discontinued the azathioprine and methotrexate, and continued the prednisolone and hydroxychloroquine. A follow-up CT scan after 6 months showed no further disease progression (Fig. 1C). The patient's symptoms, including dyspnea on exertion, improved markedly. There was no change in pulmonary function, diffusion capacity, or arterial blood gas analysis on follow-up. The patient continues to be followed in the ambulatory care clinic.

DISCUSSION

In LIP, lymphocytes and plasma cells diffusely infiltrate the lungs. The lymphocytes, which consist of polyclonal B and T cells, are distinguished from malignant lymphoma by the proliferation of monoclonal B cells. Some investigators believe that LIP might occur prior to malignant disease. Malignant lymphoma has reportedly developed from LIP [8]. The cause of LIP is not known. However, it is thought to be related to autoimmune phenomena because it is associated with SS, pernicious anemia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, idiopathic biliary cirrhosis of the liver, and chronic active hepatitis. In addition, it has been reported with HIV and Epstein-Barr virus [4,9].

Single or combination steroid therapy has been used with success; however, the effect of treatment on disease duration and side effects are unknown. According to some reports, 52% of patients with LIP improved with this treatment, and 11% of them remained clinically and radiographically unchanged. In general, approximately 37% of these patients become fatal after a mean of 20 months following diagnosis [4,9].

When SS involves the respiratory system, interstitial lung disease and tracheobronchial sicca are the most common abnormalities. In addition, pleuritis and pulmonary vasculitis may occur [10,11].

Interstitial pneumonia is observed in about 25% of all patients with SS. CT scans may have a variety of different findings, but clinically significant findings are rare. Lung biopsy is usually not necessary. A biopsy is indicated when the symptoms associated with the interstitial pneumonitis are severe or unresponsive to therapy; in these cases, malignant lymphoma must be ruled out.

It is well known that primary SS is associated with interstitial pneumonia. However, a nonspecific interstitial pneumonia is more common. The frequency of an organizing pneumonia, common pneumonias, and LIP are similar in patients with primary SS [12]. The treatment for the interstitial pneumonia associated with primary SS generally includes steroids, cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine. The standard therapy for LIP has not been established. Other immune suppressants, based on the success of steroid treatment, have been used empirically. Although new medications have been tried for treatment of SS, including etanercept, infliximab, and interferon-α, their efficacy has not been proven [2]. Rituximab, a monoclonal antibody against cell surface marker CD20, may offer an effective treatment option for all of the symptoms associated with SS [13,14].

In our case, the associated interstitial pulmonary disease was treated with azathioprine, methotrexate, and steroids; however, this regimen was unsuccessful. After the diagnosis of LIP was confirmed by an open lung biopsy, cyclophosphamide pulse therapy was added and continued for 6 months; symptoms then improved. There were no progressive findings on the pulmonary function test or chest CT results. In the future, rituximab may be considered for progressive disease.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.