Eosinophilic organ infiltration without eosinophilia or direct parasite infection

Article information

To the Editor,

Eosinophilia is usually defined as the presence of more than 500 eosinophils/mm3 in peripheral blood, and is often accompanied by tissue infiltration [1]. Massive eosinophil infiltration can generate an abscess or granuloma and result in tissue destruction [2]. Focal eosinophilic infiltrations are relatively common in the lung and liver, and are often associated with a parasitic infection, drug hypersensitivity, allergic disease, collagen vascular disease, or malignancy [3]. The presence of peripheral eosinophilia or evidence of direct parasite infestation can provide important insight to assess eosinophilic organ infiltration or abscesses. Most patients diagnosed with eosinophilic abscesses have peripheral blood eosinophilia. Some groups have reported that the number and extent of these foci seemed to be closely related to the eosinophil count in peripheral blood [3]. However, with the exception of eosinophilic infiltration in the gastrointestinal tract, for example in the esophagus or stomach, there have been no previous case reports of patients with eosinophilic organ infiltration without eosinophilia or direct parasitic infestation. Rather, most patients with eosinophilic organ infiltration have moderate to severe eosinophilia (> 1,500/mm3), especial ly primary eosinophilia (clonal eosinophilia or idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome) [3,4]. Here, we report a case, detected during regular follow-up due to colon cancer, in a patient with a newly developed eosinophilic liver abscess proven by liver biopsy, and multiple cavitary lesions in both lungs without any evidence of eosinophilia or parasite infection.

A 55-year-old female had been diagnosed with ascending colon cancer and had undergone right hemicolectomy followed by six courses of adjuvant 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy. She was regularly followed-up by chest X-ray, abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan, and laboratory tests, including complete blood count, chemistry, and tumor marker (carcinoembryonic antigen, CEA), every 6 months for 4 years at the cancer center in our hospital. There was no evidence of cancer recurrence.

At a recent regular visit, multiple newly developed small hepatic lesions in both hepatic lobes were detected on abdominopelvic CT. In addition, numerous cystic and cavitary lesions with multiple nodules were identif ied in both lungs on chest CT. These lesions in the liver and lung were not seen in previous CT scans. She was admitted for further evaluation because of suspected tumor metastasis. However, she had no subjective symptoms, such as itching or fever, and her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status was zero. No lesions suggestive of malignancy were seen on mammography or gynecological examination, and no skin lesions were revealed by physical examination. On admission, serum eosinophil count was 90/µL, and there had been no eosinophilia for the 4 years since the initial diagnosis of colon cancer. In serological tests, antibodies to Toxocara, Clonorchis, Paragonimus, Cysticercus, and Sparganum all gave negative results, and serum total immunoglobulin E (IgE) was 108 kU/L. Serum CEA was 2.5 ng/mL and was constant.

Position emission tomography-CT confirmed the presence of multiple cavitary nodules in both lungs with mild hypermetabolic activity of SUVmax = ~1.2, at the same locations as the lesions seen in chest CT scans. However, there were no hypermetabolic lesions indicative of cancer recurrence or infection in the abdomen. Subsequently, ultrasonography-guided liver core-needle biopsy was performed, targeting the inferior segment of the right lobe where a hypoechoic mass-like lesion was seen. Pathological examination of the biopsy tissue revealed an eosinophilic abscess that contained no malignant cells (Fig. 1). Immunohistochemical staining of the liver tissue also revealed no cells immunopositive for thyroid transcription factor-1, cytokeratin 20, or the homeobox protein CDX2 (a marker of intestinal differentiation). Biopsy confirmation of the multiple cavitary lesions was not possible because of their small size and the risk of complications.

Pathological examination of the liver biopsy specimen revealed an eosinophilic abscess that contained no malignant cells (A, H&E, × 400; B, H&E, × 1,000).

In a review of past history, the patient denied eating any raw foods, such as bovine liver, minced raw beef, freshwater fishes, or herbal medication. The medication that she had been taking continuously for several years consisted of a β-blocker (bisoprolol), an angiotensin receptor blocker (losartan) for hypertension, and fenofibrate (procetofene) for dyslipidemia. In addition, she had not taken systemic corticosteroids that may have affected her eosinophil blood count during the six courses of 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy.

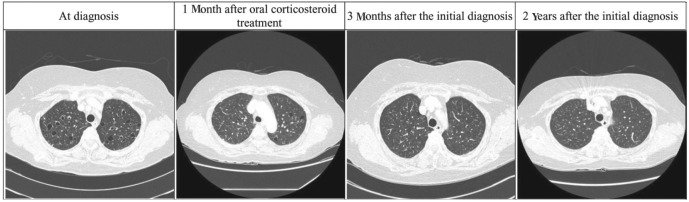

Although there was no evidence of malignancy in the liver biopsy, it was necessary to confirm that the infiltration was due to eosinophils. Therefore, we administered 30 mg of oral prednisolone twice per day for 14 days to determine whether the lesions contracted. In addition, 400 mg of albendazole twice per day for 2 weeks and 1,800 mg of praziquantel three times per day for 2 days were also administered because of the possibility of concurrent parasitic infection. When we performed chest and abdomen CT scans 1 month later, the primary liver lesion had decreased from 14 to 8 mm (Fig. 2), and the number and size of lesions in the lungs were markedly reduced (Fig. 3). After 3 months, CT showed that the lesions in the liver and lungs had almost disappeared without further medication. CT findings 2 years after the patient had presented with eosinophilic organ infiltration revealed no significant lesions in the liver or lungs.

Chest computed tomography scans. The cystic and cavitary lesions with multiple nodules seen at diagnosis in both lungs improved over time.

Eosinophilia is often accompanied by eosinophilic organ infiltration, especially in the lungs and liver. Previous reports regarding eosinophilic infiltration of organs indicated that eosinophilic infiltration of the esophagus or stomach often occurs without evidence of eosinophilia. However, eosinophilic infiltration of internal organs other than the gastrointestinal tract is almost always accompanied by eosinophilia or direct parasitic infection. In the present case, eosinophilic infiltration of the liver and lungs occurred without any evidence of eosinophilia or direct parasitic infection.

Eosinophilic organ infiltration develops in two ways. In the first, it is a consequence of the eosinophilia itself. Moderate to severe eosinophilia often leads to organ infiltration, resulting in organ damage due to the release of cytotoxic granule proteins, such as eosinophil major basic protein and eosinophil cationic protein, as well as inflammatory lipid mediators [3,4]. Irrespective of the cause of the eosinophilic infiltration, the infiltrated organs are the skin, lungs, liver, brain, and most importantly the heart [1,3]. The other cause of eosinophilic organ infiltration is direct parasitic invasion. Some parasitic infections, such as fascioliasis and toxocariasis, produce focal lesions in the hepatic parenchyma due to either direct penetration or hematogenous migration to the liver. These lesions are caused by immature worms arrested during migration, and therefore they contain worms [3]. In the present case, there was no evidence of parasite infestation in the tissue biopsy.

Due to the patient's history of colon cancer, it was necessary to consider the possibility of cancer recurrence when newly developed multiple nodules were identified in the liver and lungs. There have been anecdotal reports of eosinophilic abscesses mistaken for metastasis and radiological reports of eosinophilic organ infiltration. The nodules in the liver in this case were single, small, and infrequent, consistent with our previous observation that eosinophilic infiltrations in cancer patients involve fewer and smaller nodules than metastatic nodules [5]. Although the lung lesions could not be confirmed by biopsy in this case, they shrank after treatment with oral corticosteroids, indicating that they must also have been eosinophilic infiltrations. In addition, the level of CEA, a marker of colon cancer, also tended to be constant.

As the patient had regularly undergone complete blood counts and abdominopelvic and chest CT scans, and had no previous history of systemic corticosteroid treatment, the eosinophilic infiltrations were clearly newly developed. However, their cause remains unclear. A diagnosis of hypereosinophilic syndrome is not appropriate as there was no eosinophilia. The likelihood of a causal relationship with the malignancy is very low, because there was no evidence of tumor recurrence. The possibility of parasite infestation was also low, considering the negative enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay findings, the absence of any history of ingestion of raw food, and the nearly normal serum levels of total IgE [5]. Consequently, we should bear in mind that eosinophilic infiltration in multiple organs can develop without blood eosinophilia or direct parasitic infestation, although its incidence is low.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.