The specialist physician’s approach to rheumatoid arthritis in South Africa

Article information

Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is expected to increase in Africa and South Africa. Due to the low numbers of rheumatologists in South Africa, specialist physicians also have to care for patients with RA. Furthermore several new developments have taken place in recent years which improved the management and outcome of RA. Classification criteria were updated, assessment follow-up tools were refined and above all, several new biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs were developed. Therefore it is imperative for specialist physicians to update themselves with the newest developments in the management of RA. This article provides an overview of the newest developments in the management of RA in the South African context. This approach may well apply to countries with similar specialist to patient ratios and disease profiles.

INTRODUCTION

In view of new developments in the approach to the management of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), with more successful remission rates, it is important for all medical specialists to be updated with the new knowledge. It is important to establish early diagnosis and treatment in order to minimize radiological joint damage. There is a 6-month window of opportunity to commence treatment to minimize joint damage. The new South African recommendations provide up to date guidelines to optimize management of RA.

HEALTHCARE IN SOUTH AFRICA

South Africa is a middle income country with a diverse economy with wide income disparities [1]. South Africa currently is in the midst of a health transition characterised by epidemic infectious diseases and a rise in non-communicable diseases, which has exposed the suboptimal performance of the health system [1]. South Africa has a two tiered healthcare system. The public health care system provides health care to an estimated 80% of the population. The public healthcare system is allocated about 4% of gross domestic product (GDP) through unconditional grants. The private care system provides care to all people with medical insurance which comprise of an estimated 20% of the population. This health care system comprises of a network of private hospitals and the level and quality of healthcare compare to the best health care systems in the world. Employment of doctors in private and public sectors combined fall short of global ratios and international benchmarks for in-hospital care [1]. The latest reports shown that South Africa had 0.7 physicians per 1,000 population [1]. This situation causes that specialist physicians should have in depth knowledge of non-communicable conditions like RA.

RHEUMATOLOGY IN SOUTH AFRICA

The estimated population of South Africa is 51 million [1]. Rheumatology became a subspeciality in South Africa in the mid-nineties. This group is very active and almost all rheumatologists are members of the South African Rheumatism and Arthritis Association (SARAA). Annual meetings are held, which are well attended by all SARAA members and there is an active website for constant interaction (www.saraa.co.za). Currently there are about 64 registered rheumatologists in the country which gives an estimated ratio of one rheumatologist for every 820,000 inhabitants. Due to this ratio, all rheumatological conditions do not end up with rheumatologists. Specialist physicians in the country are confronted on a daily basis with complicated joint conditions. Therefore there is a need for general specialist physicians in South Africa to also have an in depth knowledge of rheumatology and specifically RA.

It is worth mentioning that South Africa also can contribute to the global knowledge of rheumatology with conditions typical to this region. Mseleni joint disease is a typical condition of premature severe hereditary osteoarthritis of the hip joints. The condition is limited to a specific geographical region in northern Kwazulu Natal [2]. Due to the high incidence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease in South Africa, typical features of HIV arthropathy are dealt with frequently and well described [3]. Arthralgia is present in 46% of the HIV population. Reiters syndrome is 100 to 200 times more prevalent as compared to a non-HIV population (typical the so called AIDS foot). Psoriatic arthritis is 10 to 40 times more prevalent than a non-HIV population. Typical bone lesions are subchondral necrosis of the femur head and humerus head. Septic arthritis and tuberculosis (TB) of the spine are more common in this population. Patients with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma typically present with osteolytic lesions. A South African rheumatologist, Asherson [4] described the Asherson syndrome of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. This patients present mainly with multiorgan failure resulting from predominantly small vessel occlusions. It affects mainly intra-abdominal organs such as bowel, liver, pancreas, and adrenals, although large vessel occlusions do occur and comprise mainly deep vein thromboses of the veins of the lower limbs and arterial occlusions causing strokes and peripheral gangrene.

Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in Africa and South Africa

During the past 20 years 10 population based studies were done in Africa to determine the prevalence of RA in Africa [5,6]. In general there seems to be an increase in prevalence with urbanization. In view of the fact that the African continent is the fastest urbanizing continent, the numbers of RA will increase in future. No environmental factor was identified during these studies to explain this phenomenon. The “hygiene hypothesis” associated with modern lifestyle may partly explain the phenomenon [7]. The combined prevalence was calculated to be 0.7% which is lower than the estimated world prevalence of 1% [5]. It should be kept in mind that the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1987 criteria [8] was used which is less sensitive than the new 2010 ACR/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) criteria.

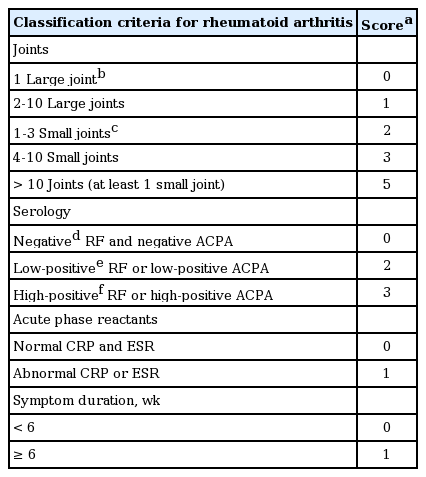

ACR/EULAR 2010 CLASSIFICATION CRITERIA FOR RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS

During the last 20 years with the invention of biological agents, the outcome of RA dramatically improved [9]. Early institution of modern therapies can prevent individuals from reaching chronic erosive disease state that is exemplified in the 1987 criteria for RA [8]. Furthermore several studies has shown that early aggressive treatment can reduce joint damage. The 1987 criteria was not sensitive enough to detect RA at an early stage and due to this bone destruction were already present at the point of diagnosis and the window of opportunity was lost. Therefore the international groups developed a more sensitive classification criteria in 2010 to ensure earlier diagnosis and earlier treatment [10]. The criteria was developed to (1) to identify high risk individuals of chronicity and erosive damage, (2) to be used as a basis to initiate disease modifying therapy, and (3) to not exclude the capture of patients later in the disease course.

The changes from the previous criteria are the following: (1) serology: anti-citrullinated protein antibody (ACPA) included into criteria; (2) number of joints involved: early RA may present with only one or two involved joints, large and small joints (hand involvement) carry different weight; (3) subcutaneous nodules excluded: not strong independent weight for diagnosis and usually not common in early disease; (4) X-ray not included: erosions late feature and aim of treatment to prevent radiological damage, this may change in future; and (5) symmetry is not a feature of the new criteria: did not carry an independent weight in any phase of the work, in practice difficult to implement, the greater the number of involved joints the higher the likelihood of bilateral involvement.

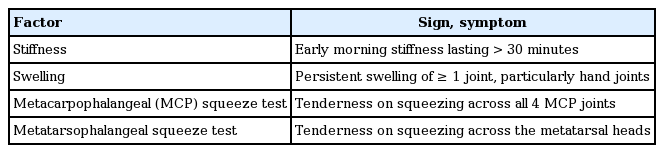

The new classification criteria is a simple well researched tool which hugely guide to the diagnosis of RA. Table 1 shows the four groups of classification criteria which are used (joint involvement, serology, symptom duration, acute phase reactants). Furthermore this classification system will ensure that the correct population receives the correct treatment. Several important clinical parameters were pointed out in the guideline document as far as intensity, prognostic markers of severity and outcome. Predictors of disease persistence in early arthritis are female gender, symptoms for more than 12 weeks, high affected joint count, hand involvement, cigarette smoking, high acute phase response, positive rheumatoid factor (RF) and positive ACPA, radio graphical erosions and fulfilment of the 1987 ACR diagnostic criteria. Predictors of joint damage are the swollen joint count, acute phase reactants, RF, ACPAs, shared epitope and erosive disease. Predictors of functional disability are female gender, high tender joint counts, high health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) score, acute phase reactants and erosive disease. The clinical evaluation of a person with arthralgia remains of utmost importance. The symptoms and signs of joint inflammation (early morning stiffness longer than 30 minutes, swelling, constitutional symptoms of tiredness, weight loss, and anorexia) with involvement of more than one joint, are important clues to the diagnoses.

The 2010 American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis

The serology markers of RA not only assist in confirming the diagnosis of RA. It also predicts the prognosis of the condition. ACPA and/or RF auto antibodies are present in nearly 50% of patients prior to symptomatic onset of RA. However, it should be kept in mind that the diagnosis of RA can be made without seropositivity. Alongside C-reactive protein and joint erosion scores, RF and ACPA positivity predicts rapid progression in RA.

SOUTH AFRICAN GUIDELINES FOR RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS TREATMENT

In view of the new international RA criteria, newer assessment methods and more treatment modalities, a task group of South African rheumatologists developed guidelines for the South African context [11]. The South African context is unique due to the high burden of infective diseases (HIV infection the highest in the world, hepatitis, and high prevalence of TB infections). Against the background of recent major developments in the management namely (1) advances in the early diagnosis of the disease and evidence for the benefit of early therapy; (2) better tools to assess response to therapy with the development of composite disease activity scores, allowing goal-directed therapy where the target is remission; and (3) the emergence of biologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), the South Africa guidelines were developed. These strategies result in better control of inflammation, thus preventing joint damage and reducing disability. Therefore the SARAA have proposed the development of an updated treatment strategy for the effective therapy of RA in South Africa. These recommendations are aimed at all healthcare professionals managing RA, including rheumatologists, physicians, general practitioners, nurses, and allied healthcare professionals [11].

THE KEY PRINCIPLES OF THE GUIDELINES

Early diagnosis and treatment

Untreated RA results in severe disability and loss of health-related quality of life [12]. There is a direct relationship between the duration of uncontrolled inflammation and joint damage (as measured by bony erosions and joint space narrowing) [13]. Joint damage begins within the first 3 to 6 months after disease onset and a narrow window of opportunity exists where early aggressive therapy of RA can suppress inflammation before irreversible joint destruction has occurred [14-16]. Early diagnosis and prompt referral to a specialist, or to a rheumatologist, for initiation of DMARDs is critical. The ACR/EULAR therefore have developed updated criteria for the classification of RA (Table 1) [10]. These new criteria may enable practitioners to make a much earlier diagnosis of RA than the previous ACR criteria [8]. Screening tools, such as the ‘S-factor’ developed by Arthritis Research UK and the Gait, Arms, Legs, and Spine (GALS) examination, may support primary healthcare workers in diagnosing inflammatory arthritis. This will result in earlier timeous referrals to specialists to initiate DMARDs (Table 2) [17,18]. Efforts should be made to increase awareness amongst primary carers of the early signs of inflammatory arthritis (positive squeeze test of hands and/or feet with joint stiffness after immobility) [19].

ASSESSMENT

Disease activity

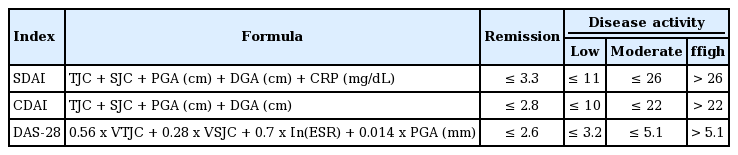

Significant advances were made in the methods of scoring disease activity in RA, where the clinical examination of tender and swollen joints, global assessments and laboratory investigations are combined in a composite disease activity score. The three validated scores currently in use in South Africa are the 28-joint disease activity score, the simplified disease activity index (SDAI), and the clinical disease activity index (CDAI) (Table 3) [20-22]. These scores allow classification of the patient into a state of remission or low, moderate or high disease activity. The scores provide a simple tool for assessing disease objectively at each patient follow up visit to guide therapeutic decisions [23]. The results of clinical trials can also be better standardised using the assessment tools. Treatment efficacy during trials are expressed according to the percentage of patients achieving a 20% improvement (ACR 20), 50% improvement (ACR 50) or 70% improvement (ACR 70) response [24].

Goal-directed therapy

In other fields of medicine, treatment targets have been defined and treatment aimed at achieving these targets has led to improved outcomes with less end-organ damage. Examples include hemoglobin A1c level in diabetes mellitus, blood pressure measurement in hypertension and cholesterol level in dyslipidemia. In RA, there is evidence that obtaining tight control of disease activity allows better control of disease than routine clinical care. All patients should have low disease activity (LDA) or be in remission. This intensive control strategy results in lower disease activity, better physical function and less structural damage, particularly when commenced in early disease [25]. For this reason, RA patients commenced on therapy may require evaluation as frequently as monthly, with calculation of a composite disease activity score at each visit. Escalation of DMARD therapy takes place until LDA (SDAI ≤ 11) or ideally remission (SDAI ≤ 3.3) is achieved. Thereafter less frequent assessments (3- to 6-monthly) are acceptable. The target of LDA or remission should be maintained as long as possible, keeping in mind the individual patient’s risk for drug-related complications or comorbid diseases.

Disability

Physical disability, with its negative consequences on personal care, employment, and social life, can be measured with a self-administered questionnaire, the HAQ-disability index (HAQ-DI) [26]. In early disease, the HAQDI reflects joint inflammation and shows good correlation with clinical disease activity [27]. In established RA, physical function worsens annually as a consequence of irreversible joint damage [28]. The score ranges from 0 (no disability) to 3 (severe disability).

Radiography

Baseline radiographs of hands and feet should be performed for diagnostic and prognostic purposes [29]. Erosions seen within the first 2 years of disease are markers of aggressive disease, but normal X-rays do not exclude the diagnosis of RA. In addition, a chest X-ray (CXR) is appropriate to assess rheumatoid lung involvement and to exclude TB prior to commencing DMARDs. It also provide a baseline in the event of pulmonary complications of therapy [11]. Bone density determination is indicated before the start of glucocorticoid therapy.

Sonar and magnetic resonance imaging

Newer imaging modalities such as high-resolution ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging of peripheral joints allow detection of synovitis, joint space narrowing and erosions much earlier than conventional radiography [30]. Precise visualisation of anatomical structures allows more accurate diagnosis of joint and soft tissue pathology in the RA patient, and facilitates accurate placement of intra-articular injections. These are not yet part of routine patient management [31].

THERAPY

Synthetic disease modifying drugs (DMARDs)

Methotrexate (MTX) is the most widely prescribed DMARD and the cornerstone of RA treatment. It is recommended as first-line therapy in doses starting at 7.5 to 15 mg weekly, with rapid dose escalation according to response and tolerability to a maximum of 25 mg weekly. The drug has an excellent safety profile. Mild elevation of liver enzymes is not infrequent but usually transient, and cirrhosis is rare [32,33] There is no evidence that higher doses than 25 mg weekly are more effective and they may increase toxicity.

Antimalarials (chloroquine [CQ] or hydroxychloroquine), may be used as monotherapy for mild RA, or in combination with MTX for moderate to severe disease. Sulphasalazine (SSZ) is effective as monotherapy, and is particularly useful in patients in whom MTX is contraindicated, or as part of combination DMARD therapy. Similarly, leflunomide may be prescribed as monotherapy or co-prescribed with MTX. A summary of the doses, major side-effects and recommendations for monitoring patients is presented in Table 4, and further details have been given in previous South Africa guidelines for RA [34]. Patients who have failed MTX monotherapy should be treated with combination synthetic DMARDs. The most commonly prescribed combination treatment is MTX, SSZ, and CQ.

Glucocorticoids

Glucocorticoids (GCs) rapidly reduce symptoms of RA and may inhibit development of erosions, particularly in early RA when used in combination with DMARDs [35]. However, side-effects limit their long-term use, and GCs are not appropriate as monotherapy. Low-dose oral prednisone (less than 10 mg/day) is appropriate in combination with DMARDs in early RA (less than 2-year disease duration) for up to 6 months. After 6 months the symptomatic effects seem to wane. In established RA, they may be used as ‘bridging’ therapy when DMARDs are initiated, and should be withdrawn once DMARDs have controlled the disease [36,37]. Intra-articular GCs are useful for a mono- or oligo-articular flare of disease. Long-acting intramuscular methylprednisolone may be used as an alternative to oral prednisone.

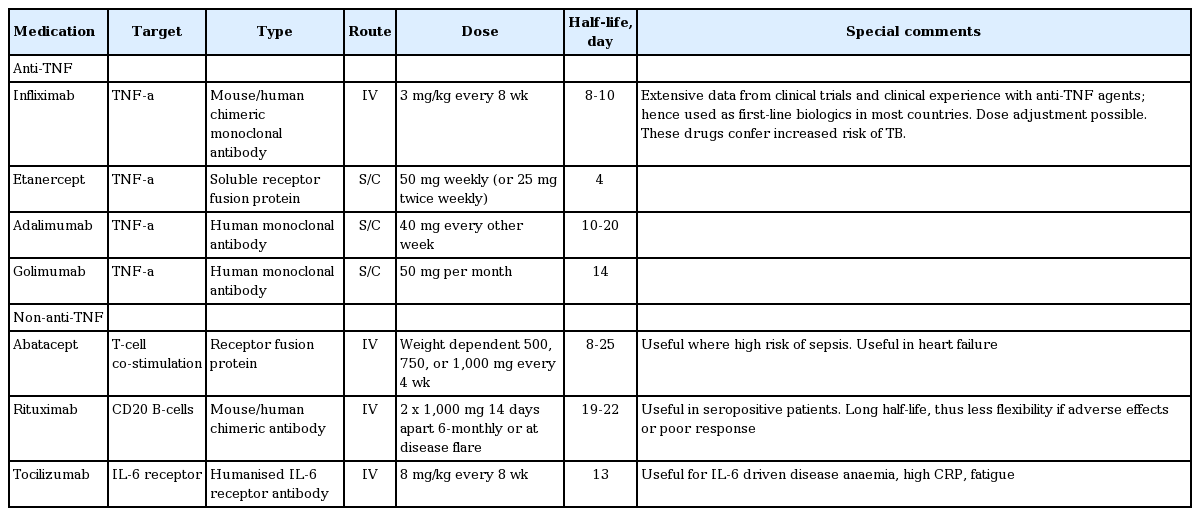

Biologic disease modifying drugs (DMARDs)

One of the most significant advances in the treatment of RA in recent years has been the development of biologic DMARDs, which are proteins directed against specific cytokines or their cell receptors. A wide choice of biologic DMARDs is now available in South Africa with excellent efficacy in controlling RA in patients who have failed synthetic DMARD therapy. Clinical trials and post-marketing experience have shown that these DMARDs treat many aspects of RA disease: suppression of joint inflammation, prevention of radiographic progression and improvement of physical function and health-related quality of life [38]. They may be classified into those inhibiting tumor necrosis factor (TNF; i.e., anti-TNF) and those targeting other cytokines or cells (non-anti-TNF). The ACR, EULAR, and SARAA have developed recommendations for the use of these agents [9,34,39]. Biologic DMARDs are usually co-prescribed with MTX to improve efficacy and reduce antichimeric antibody production. The use of combination biologic DMARDs is not recommended. Table 5 summarises the biologics currently available and provides details of dose and administration. In South Africa Biologic DMARDs are initiated by a rheumatologist, and information about patients on biologic therapy entered into the SARAA biologics registry. This process is somewhat time consuming with the result that patients who qualifies for this therapy do not get treatment as quick as ideally possible.

Timing and choice of biologic therapy

In South Africa, commencement of biologic therapy after a 6-month trial of at least three synthetic DMARDs (including MTX, unless contraindicated) is considered. This seems reasonable, given resource constraints, and given that up to one-third of patients will achieve LDA on synthetic DMARD therapy [40,41]. Indications for biologic therapy include an inadequate response to synthetic DMARD therapy, with high disease activity (SDAI > 26), or moderate disease activity (SDAI 11 to 26) in the presence of poor prognostic factors (seropositivity, radiographic erosions within the first 2 years, extra-articular complications or functional disability). The efficacy of all currently available biologic drugs has been confirmed by clinical trials and by clinical experience and the choice of drug depends on the safety profile and on the patient’s preferred route of administration. At present, the optimal sequence of biologics remains unclear. In future, genome biomarkers may assist in identifying the most appropriate biologic agent for an individual patient [42]. A biologic DMARD that has not resulted in an adequate clinical response after 6 months of treatment should be replaced with another biologic DMARD [43].

Analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs

Analgesics should be prescribed and taken on an ‘as needed’ basis for pain control. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective in controlling pain and stiffness, but are purely symptomatic therapies and offer no disease-modifying action. The toxicity of these drugs should not be underestimated. In RA, NSAIDs are often prescribed on a long-term basis, but should be used with caution as many patients have risk factors for NSAID-induced gastrointestinal tract events. Particularly at risk are older patients (age > 60 years), as well as those who are co-prescribed corticosteroids and aspirin. Hence, there should be a low threshold for co-prescribing a proton pump inhibitor for gastroprotection, or for considering a COX-2 selective agent (COXIB) [44]. In addition, all NSAIDs, both non-selective agents and coxibs, confer an increased risk of thrombotic events and should be used with caution in patients with cardiovascular risk factors [45]. Other side-effects of NSAIDs, including hypertension, renal and liver dysfunction should be kept in mind. Blood pressure should be checked within a month of initiating NSAID therapy. Ideally, NSAIDs should be used in the lowest effective dose and for the shortest duration of time, and withdrawn if possible once disease activity is controlled with DMARDs.

Extra-articular disease

Moderate to high-dose GCs, sometimes combined with other immuno-suppressant drugs, are used in severe extra-articular disease including serositis, vasculitis, and scleritis [11]. The necessary vigilance for osteoporosis should be practised in this group of patients.

Multidisciplinary team

Care of the RA patient requires a multidisciplinary approach with referral to an occupational therapist, podiatrist, physiotherapist, clinical psychologist and social worker, as appropriate. A rheumatology nurse can offer patient education and support, with positive effects on adherence to therapy and on health-related quality of life [46]. Adoption of a healthy lifestyle that includes regular exercise, loss of weight (if overweight) and discontinuation of smoking is of benefit. Smoking has been shown not only to increase the risk of developing RA, but also to worsen the severity of joint disease, extra-articular complications, and comorbidities of RA [47]. Referral of the RA patient for orthopaedic surgery may be appropriate in certain circumstances. Importantly, surgical treatment of RA is only an adjunct to medical control of the disease with DMARDs. With modern aggressive therapy of RA, the number of patients requiring joint replacements and other surgical interventions is declining [48].

COMPLICATIONS AND SAFETY ISSUES

Tuberculosis

South Africa has of the highest prevalence of TB in the world. Furthermore, all RA patients are at increased risk of TB. This risk is increased by drugs used to treat RA including GCs, MTX, and biologic drugs, in particular anti-TNF therapy [49]. The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF plays an essential role in the containment of mycobacterial infection in granulomas. Inhibition of TNF may lead to reactivation of latent TB, or possibly to new TB infection [50]. This reactivation of TB generally occurs within the first 3 to 6 months after initiation of anti-TNF therapy. The presentation may be atypical, with over half of cases reported as extra-pulmonary, and a high proportion of disseminated TB [51]. Each patient requires screening for latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) and an assessment of the risk of TB infection/reactivation (risk stratification).

Screening for latent tuberculosis infection

The efficacy of screening for and treatment of LTBI before initiation of anti-TNF therapy has been well demonstrated, but the most appropriate test to detect LTBI in South Africa is uncertain [51-53]. In a high prevalence setting such as South Africa, there is no reliable test for LTBI. The tuberculin skin test (TST) has traditionally been the primary tool for identifying LTBI, but limitations include false-negative results in immunocompromised patients (for example patients on immunosuppressive drugs such as MTX or corticosteroids [54]) and a false-positive test after bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination at birth, although this is not believed to be very significant amongst adults [55]. Other problems with the TST are the logistics of return visits for evaluation and variations in administration and interpretation of the test [56]. Despite this, detection of LTBI by TST (defined as induration ≥ 5 mm) is highly effective. Recently, interferon γ (IFN-γ) release assays (IGRAs), which measure IFN-γ response to TB-specific antigens, have been introduced. While excellent performance and good cost effectiveness of these tests have been reported [57], a negative IGRA does not exclude LTBI. In low-prevalence settings, the combination of TST and IGRA may be the best strategy [58]. Currently, there is little consensus on the most appropriate screening test in high-prevalence settings such as South Africa [59]. A patient due to commence biologic therapy should have a TST, an IGRA test (if deemed appropriate by the clinician), and a CXR. An abnormal CXR suggesting active pulmonary TB clearly needs investigation, and treatment for the patient. A patient with a positive TST, and a normal CXR, should be given anti-TB chemoprophylaxis. Extrapolating from studies in HIV-positive patients, chemoprophylaxis may be either isoniazid (INH) for 9 months, or rifampicin combined with INH for 3 months [60]. The current consensus is that anti-TNF therapy can be initiated after completion of a minimum of 1 month of chemoprophylaxis.

TB risk stratification

The incidence of TB in South Africa is amongst the highest in the world, with an estimated incidence of 808 per 100,000 in the general population [61]. In light of this, there are valid concerns regarding the safety of anti-TNF drugs and all patients must be considered to be at relatively high risk of TB. In the absence of prospective data, recommendations must err on the side of caution. The risk of developing active TB in RA patients treated with biologic DMARDs appears to depend on the background prevalence of LTBI. Factors associated with LTBI in the USA and in Hong Kong include older age, residence or travel in a TB-endemic area, high-risk occupation (healthcare or institution worker), previous TB infection, Felty’s syndrome, and low socioeconomic status [62,63]. Concomitant corticosteroid use and monoclonal rather than soluble anti-TNF drugs seem to confer a higher risk for TB [53,64,65]. Non-anti-TNF therapy appears to confer a much lower risk of TB, but cases have been reported [66].

Very high-risk patients

Patients who are stratified as being at very high risk of LTBI and who require biologic therapy need careful consideration. Risk factors include healthcare workers, inmates, or employees at institutions (like prisons and old age homes), patients who have had previous TB, a poor socioeconomic background and overcrowding. If such a high-risk patient is to commence anti-TNF therapy, a strategy offering 9 months of INH prophylaxis, regardless of TST/IGRA result, may be appropriate. Such a policy has also been adopted in India because of the high incidence of TB [67]. Despite concerns of INH toxicity and of propagating INH-resistant TB, this strategy may be valid in high-risk settings such as South Africa. Longer-term chemoprophylaxis, continued for the duration of anti-TNF therapy, may be appropriate in very high-risk patients, but there are no prospective data. Alternatively, non-anti-TNF drugs may be the safest choice of first-line biologic therapy in such patients. This is the current practice in Algeria and Morocco, and has also been shown to be effective in high-risk patients in Germany [68,69].

Other infections

There is an increased risk of infection amongst RA patients, particularly in patients treated with biologic therapy [38]. These include serious bacterial infections, as well as opportunistic fungal (histoplasmosis in particular), Listeria and non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Hence, biologic drugs should be used with caution in patients with chronic infected leg ulcers, septic arthritis in the preceding 12 months, septic arthritis of prosthetic joints, recurrent urinary, or respiratory tract infections, an indwelling urinary catheter, or hypogammaglobulinemia.

In the presence of active infection, administration of a biologic drug should be delayed. MTX does not increase the risk of sepsis or perioperative complications in patients undergoing joint replacement surgery, and can be continued. There may be a small risk of perioperative infections in patients using biologic DMARDs, and it is recommended that these drugs are discontinued prior to surgery for a period of 3 to 5 times the half-life of the drug and resumed after good wound healing.

HIV infection

In South Africa, the burden of HIV infection is amongst the highest in the world, with an estimated 33% of females between the ages of 25 and 29 years infected in 2010 [70]. This pandemic has both diagnostic and therapeutic implications for the management of patients with concomitant inflammatory arthritis [3].

HIV infection can cause, among other musculoskeletal syndromes, inflammatory polyarthritis mimicking RA [71]. Hence, an HIV test may be appropriate in a patient presenting with inflammatory arthritis. There are several challenges in the management of RA patients who are HIV-positive. Information on the safety of using immunosuppressive drugs in an HIV-positive patient is limited. MTX and biologic drugs place patients at risk of opportunistic infections and there is concern of added immunosuppression if prescribed in an HIV-positive patient [72]. For this reason, these therapies are not recommended and CQ (which may have antiviral properties [73]) or SSZ may be more appropriate choices. In addition, there are difficulties in the assessment of disease activity in HIV-positive patients due to the nonspecific increase in erythrocyte sedimentation rate associated with HIV infection [74]. Little is known about the effect of antiretroviral therapy (ART) on RA disease, or the safety of biologic drugs in patients receiving ART. These are areas for future research.

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis B reactivation can occur in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients treated with MTX or biologic therapy (particularly rituximab). Thus, screening for viral hepatitis before starting treatment in high-risk patients is recommended [75]. Hepatitis B vaccination should ideally be offered to non-immune patients before commencing DMARD treatment. In hepatitis C-infected patients, anti-TNF therapy and rituximab is considered safe, and possibly beneficial [76].

Vaccination

Patients with RA should receive killed vaccines based on age and risk, ideally at least 14 days before commencing DMARD or biologic therapy for optimal efficacy. These might include influenza, pneumococcal, hepatitis B and human papillomavirus vaccines. Live vaccines including herpes zoster and yellow fever vaccines are not recommended in RA patients on MTX or biologic therapy. It may, however, be appropriate to vaccinate a patient likely to travel to a high-risk yellow fever area, prior to commencing biologic therapy [11].

Cardiovascular events

Due to a combination of systemic inflammation and traditional cardiovascular risk factors, patients with RA have increased cardiovascular disease and risk of cardiovascular death, similar to that seen in patients with type 2 diabetes [77]. Traditional risk factors including smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia (most importantly low levels of high density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol and resultant high total cholesterol to HDL ratio) need to be addressed [78]. In South Africa, treatment of dyslipidemia is based on cardiovascular risk estimation using the Framingham risk score [79]. In the setting of RA that is seropositive, extra-articular, or established (≥ 10 year disease duration), this percentage risk should be multiplied by 1.5 [78]. Uncontrolled severe joint inflammation, extra-articular disease, physical inactivity, and corticosteroid use further contribute to the risk of cardiovascular events [80]. Improved disease control with therapy, such as MTX and anti-TNF therapy, has been shown to decrease cardiovascular risk in RA patients [3,81].

Osteoporosis

Bone loss is an important consequence of long-standing RA and patients may require co-therapy with osteoclast-inhibiting agents or osteoblast stimulators. The pathogenesis of osteoporosis in RA is multi-factorial and can be cumulative over time. In early disease, the predominant feature is localised, or juxta-articular, osteoporosis, which is a consequence of locally acting pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is not yet clear whether biologic DMARDs are capable of retarding or reversing bone loss in RA, but studies are under way to evaluate this. One recent study failed to show a significant impact on bone density following anti-TNF therapy, but the sample size and duration may have meant that it was underpowered [82]. Generalised osteoporosis affecting the femur and lumbar spine is usually seen in long-standing RA, especially in post-menopausal women. The mechanism is likely to be due to a combination of immobilisation, age, menopause, GC therapy and inflammation due to RA. The dose of prednisone associated with bone loss is likely to be as low as 2.5 mg daily [83]. The ACR has recently published revised guidelines for the treatment of GC-induced osteoporosis, recommending that a lower threshold for intervention be used. In general osteoporosis cases are undertreated. Fractures in these patients may occur when the bone mineral density T-score is –1 to –2.5 (osteopenic) [84]. Should a daily GC dose of more than 7.5 mg be used for longer than 3 months, bisphosphonates should be commenced to prevent osteoporosis. Calcium and vitamin D supplementations are recommended for routine use in all patients likely to receive GC therapy for longer than 6 months, irrespective of dose. Control of joint inflammation with DMARD therapy will help to maintain the bone density by improving physical activity.

Malignancy

Patients with RA are at increased risk of lymphoma with the major risk being uncontrolled joint inflammation rather than DMARD therapy [85]. Neither synthetic nor biologic DMARDs seem to confer an increased risk of malignancy [86,87], nor do they increase the chance of recurrence of a malignancy, or change the prognosis of cancers that occur in patients using biologic therapies [88]. The current recommendations are that biologic therapy be avoided in patients with a current or recent (< 5 years) diagnosis of a malignancy.

Pregnancy

RA tends to improve during pregnancy. In general, because of potential risks to the fetus, DMARDs are not recommended and low-dose GCs may be adequate to control symptoms. MTX and leflunomide are contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding, but SSZ and CQ are considered relatively safe and may be useful in active disease. There is sparse evidence for the safety of biologic drugs in pregnancy or lactation and formal recommendations are that anti-TNF drugs and rituximab be stopped 3 and 12 months, respectively, before conception. However, there are recent reports of successful pregnancies in patients using anti-TNF drugs, and many experts feel that these drugs can be safely continued during conception and the first 2 trimesters of pregnancy [89].

Monitoring patients on therapy

Disease activity should be evaluated with an SDAI. An intensive disease control strategy should be used with escalation of therapy if LDA or, ideally, remission is not achieved. Patients with moderate or high disease activity should be assessed frequently (1 to 3 monthly) until an LDA state is achieved, after which less frequent visits (3 to 6 monthly) are acceptable [11]. Monitoring for toxicity of DMARD therapy is summarised in Table 5. There is no indication for ‘routine’ liver biopsy in patients on MTX therapy. A biopsy may be indicated in a patient with persistently elevated liver enzymes (more than three times the upper level of normal) after DMARD discontinuation [90]. Annual serum creatinine and cholesterol tests are appropriate. Baseline bone mineral density measurements are recommended in postmenopausal women starting long-term GC therapy and should be repeated at yearly intervals. Bone density should be considered at 6 monthly intervals where patients are on GC treatment of more than 7.5 mg daily for more than 3 months. Because of the high risk of infection, including TB, RA patients and their physicians must remain vigilant for symptoms of infection. Patients should be advised to seek medical attention for any symptoms of possible infection to allow for prompt assessment and treatment. Loss of weight, fever, or lymphadenopathy in a patient on biologic therapy requires prompt investigation for TB, which might include a CXR, abdominal ultrasound, and bone marrow aspiration.

Economic aspects of therapy

The costs of therapy to treat RA, which may include the considerable expense of biologic drugs in patients who do not respond to synthetic DMARDs alone, need to be balanced against the consequences of uncontrolled disease with ensuing joint damage and disability. Loss of productivity in the home and workplace, loss of income, isolation from society, and reduced recreational comforts, together with the negative psychosocial impact of the disease, have severe economic consequences for patients, their families, and to society [11]. The measures used to quantify these effects include the disability adjusted life-years and the quality of life-years lost. The costs of therapy will be relatively low in patients receiving non-biologic DMARDs, but will escalate when biologic DMARDs are added. When comparing different therapies for the treatment of RA, the number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve a response may be a useful reference. Such calculations will differ depending on the tool used to measure response. Most studies base their calculations on achieving an ACR 50 response in a 70 kg subject. A recent meta-analysis of the cost-effectiveness of all biologics showed that the NNT varied between 2.8 and 5.7 [91]. A recent systematic review of the literature, which contributed to the EULAR recommendations, showed that the merits of effective control of RA outweigh the costs of therapy. At disease onset, synthetic DMARDs should be initiated. If these fail, treatment escalations with biologic therapy are cost-effective, provided standard dosing schemes are used.

PROFILE OF RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS PATIENTS IN A SPECIALIST PHYSICIANS PRACTICE IN BLOEMFONTEIN, CENTRAL SOUTH AFRICA

Due to the low numbers of rheumatologists in South Africa, specialist physicians also care for RA patients. A cohort of 75 patients who were evaluated at a specialist physicians practice was entered onto a database to establish the health profile of patients seen by specialist physicians. All patients were confirmed as RA according to the ACR/EULAR 2010 classification [10]. The male to female ratio was 1:3. The average age was 57 years and the average duration of disease was 8.46 years. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of disease duration. Disease activities score (CDAI) distribution is shown in Figs. 2 and 3 show associated medical conditions. Co-existing hypertension was present in 22% of subjects. Hypothyroidism, dyslipidemia, diabetes, asthma, and depression were all present in 5% of subjects or more. Therefore it is suggested that a high index of suspicion should be present for patients with RA and the appropriate tests should be done to screen for these conditions. DMARD prescriptions are shown in Fig. 4. As expected, a MTX was the most used synthetic DMARD. GC usage was surprisingly high. The low cost and short term efficacy may account for this.

Duration (years) of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in a specialist physician practice in South Africa (cohort of 75 patients).

Clinical disease activity index (CDAI) scores for 75 patients with rheumatoid arthritis from a specialist physician practice in South Africa.

Number of patients with associated medical conditions in 75 rheumatoid arthritis patients from a specialist physician practice in South Africa. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; CA, cancer.

AREAS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

There are several areas for future research to provide answers to optimal RA management in our unique South Africa situation [11]. The most important issues revolve around TB, including the safety of biologic DMARDs, and the risk factors for development of TB. Contemporary epidemiological data on the prevalence and incidence of RA in South Africa are needed. Other areas for investigation include management of RA in HIV-positive patients, the burden of RA on productivity in South Africa and local exploration of the cost-effectiveness of RA treatment. Due to recent advances in RA therapies, it is suggested that these recommendations are updated every 2 years.

CONCLUSIONS

It is important for specialist physicians to adopt the new classification criteria for RA in order for early detection of RA. Early aggressive therapy to reach LDA or remission is important to minimize radiological damage. Primary care physicians should be aware of the presentation of inflammatory arthritis for earlier referral and treatment. Specialist physicians should be aware of associated medical conditions (hypertension, hypothyroidism, dyslipidemia, diabetes, asthma) and screen for it. Biological treatment has changed the face of RA treatment and newer molecules which continue to have a profound effect on the prognosis of RA.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.