Comorbidities and the use of comedications among patients with chronic hepatitis C in Korea: A nationwide cross-sectional study

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Chronic hepatitis C (CHC) is the second leading cause of liver-related mortality and is more prevalent in the elderly population in Korea. Decisions to initiate treatment and selection of proper antiviral agents may be challenging among elderly patients due to relevant comorbidities, comedications, and drug-drug interaction (DDI). It may be helpful to understand the current demographic status and comorbidities of CHC patients in the country.

Methods

Patients aged ≥ 18 years and diagnosed with CHC (KCD-7 code B18.2) were extracted from the Korean Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service database in 2018. Data on comorbidities and comedications were assessed and potential DDIs were analyzed.

Results

A total of 50,476 patients with CHC, with a mean age of 60.3 years and 46.7% male patients were identified. The proportion of patients with cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver transplantation was 6.0%, 4.1%, and 0.3%, respectively and 37.2% of patients were more than 65 years of age. The three most common comorbidities were diseases of the digestive system (83.7%), respiratory system (58.2%), and musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (57.6%). The three most common comedications were analgesics (91.6%), gastrointestinal agents (85%), and antibacterials (80.3%). Lipid-lowering agents and anticonvulsants were prescribed in 28.5% and 14.8% of patients. Rate of potential DDI for contraindication was 2.2%, 13.1%, and 15.6% with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, ledipasvir/sofosbuvir, and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir.

Conclusions

With the increasing age of patients with CHC, comorbidity, comedication, and potential DDI should be considered when choosing antivirals in Korea. Sofosbuvir-based regimens showed favorable DDI profiles among Korean patients.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection still remains a global public health issue with 170 million patients developing chronic hepatitis C (CHC), among whom 32.2 million reside in Asia [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the sixth most common cancer with 10% of cases originating from HCV infection in Korea [2]. The rising disease burden of HCV infection also reinforces the goal of the World Health Organization to eradicate HCV infection by 2030 [3] and thereby warrants the need to implement the universal national HCV screening for early diagnosis and implementation of optimal HCV infection treatment [4].

The introduction of oral direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) has resulted in an unprecedented shift in providing more efficacious and expansive treatment options for individuals with CHC with fewer adverse events as compared with the previous peg-interferon based treatments [5]. While comparing with the western countries where most of the patients are young intravenous drug users [3], the prevalence of CHC increases with age in Korea with procedures-based transmission such as acupuncture, tattooing, and piercing as the major root of transmission [6,7]. One study using the Korean National Health Insurance (NHI) claims database of 2013 has shown that 84.8% of patients with CHC had at least one comorbidity and 96.8% of the patients took at least one prescribed medication [8]. With such patient demographics, a thorough review of comorbidity and comedication is required before HCV treatment to prevent any drug-drug interactions (DDIs) [8]. This is further reinforced by the International guidelines including the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, European Association for the Study of the Liver, and Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver recommended thorough review of medications in all HCV patients to consider DDI risk prior to starting DAA therapy or other medications during treatment in all patients undergoing DAAs intervention [9–11]. It is thus paramount for physicians to understand the comorbidities and comedication profiles of patients with CHC to optimally manage chronic HCV infection along with their comorbidities [12]. With the growing importance of DDI evaluation and the updated availability of pangenotypic DAA regimens, there is a strong need to explore the comorbidities and potential DDI profiles of patients with CHC in Korea. Therefore, this study was conducted to identify the comedications, and comorbidities of Korean patients with CHC and the potential DDI of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (LDV/SOF), SOF/velpatasvir (SOF/VEL), and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (GLE/PIB), which are available pangenotypic DAA regimens in Korea.

METHODS

Study design

This retrospective, cross-sectional study used data extracted from Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service (HIRA) database from January 1st to December 31st, 2018. The HIRA database is the national claims database of Korea which covers 90% of the total population and carries compiled data from healthcare providers for patients’ actual medical service utilization across the country [13]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy (2020-1854-001) and informed consent was waived due to the study nature of retrospective data analysis.

Patient selection and data retrieval

Patients aged ≥ 18 years and have been diagnosed with Korean Standard Classification of Diseases (KCD)-7 code “B18.2 (chronic hepatitis C [CHC])”, the Korean version of the International Classification of Disease-10 codes [14] or any of its subcategories as primary diagnosis in 2018 were selected for analysis. The demographic characteristics, patients’ comorbidity profiles, and prescribed medications throughout 2018 were identified and retrieved for each de-identified patient. The patients were categorized into four subgroups by liver disease status: liver transplant (LT), HCC, liver cirrhosis (LC) as diagnosis of exclusion, and CHC patients not included in LT, HCC, or LC groups. Any patients with LT-related code of Z94.4 (LT status), or T86 (LT failure and rejection) were classified as LT group. Excluding patients with LT-related diagnosis, patients with HCC-related code of HCC (C22 [malignant neoplasm of liver and intrahepatic bile ducts], C22.0 [liver cell carcinoma], and C22.9 [malignant neoplasm of liver, not specified as primary or secondary]) were categorized as HCC group. The LC patient category was defined as all patients with LC diagnosis except for those who had LT or HCC.

Analyses of comorbidities and comedication profiles by the patients’ cirrhosis status and DAA exposure status were also conducted. The cirrhosis status is defined as whether a patient had been diagnosed with cirrhosis with the following codes, irrespective of whether the patient was categorized in the four disease subgroups: CHC (B18.2), liver cirrhosis (LC; K74 [fibrosis and cirrhosis of liver], K74.0 [hepatic fibrosis], K74.1 [hepatic sclerosis], or K74.2 [hepatic fibrosis and hepatic sclerosis]).

DAA exposure status group was identified if the selected patient was prescribed with any of the following DAA regimens at least once between 2015 and 2018: ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir (OBV/PTV/ritonavir + DSV), daclatasvir + asunaprevir (DCV/ASV), elbasvir/grazoprevir, GLE/PIB, or any regimen using SOF including SOF, SOF/VEL, LDV/SOF, DCV + SOF, ASV + DCV + SOF, and SOF/VEL/voxilaprevir (SOF/VEL/VOX).

Assessment of comorbidities

Comorbidities were captured according to the main and sub-disease KCD-7 codes and classified into disease categories. Diagnostic codes captured for ≥ 1 inpatient or ≥ 2 outpatient experiences for patients with diagnostic codes of CHC were included in comorbidity analyses. The number of comorbidities was counted by disease categories and individual disease codes. The number of patients with each disease code was counted and compared by age group, gender, cirrhosis status, and DAA exposure status.

Detailed information on KCD-7 codes and disease categories is included in Supplementary Table 1.

Assessment of prescribed comedications

The prescribed medications taken by patients with CHC were identified by main substance, ingredients, and drug classes. Classification of drugs was based on main substance information provided by Liverpool University (https://www.hep-druginteractions.org, accessed June 2020), and if the information was not available, the information provided by Peking University (http://newywxhzy.ashermed.com) was referred. The category of cytotoxic drugs includes both cytotoxic and HCC therapies, and the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) drug category includes HIV Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors, HIV entry integrase inhibitors, and HIV protease inhibitors.

The proportion of patients with each prescribed medication and the mean number of prescribed medications used per patient was calculated by drug classes. The mean number of prescribed medications per patient and the proportion of patients taking ≥ 1 medication was analyzed, and subgroup analyses were conducted stratified by age, gender, and underlying liver disease group. When a patient had been prescribed two or more medications of the same composition with different brand names, or medications with different dosages, the number of prescribed medications was counted as one based on its identical active ingredient even though the drug codes were different.

Assessment of potential DDIs between prescribed comedications and various DAA regimens against HCV

All prescribed medications to patients with CHC throughout 2018 were collected and analyzed for potential DDIs with three different DAA regimens, LDV/SOF, SOF/VEL, and GLE/PIB. The analysis was conducted under the assumption that the patients were treated by these DAA regimens with the current medical conditions and comedications. DDIs were categorized into four categories based on the information derived from Liverpool University and Pecking University: “Contraindication”, “Dose-reduction/additional monitoring required” (possible interaction; defined as the plausible need for additional monitoring and/or dose adjustments for safe administration of comedications and patient safety [15]), “No clinically significant interaction expected” (no interaction), and “No available information”. If a patient was prescribed with multiple medications in different DDI categories, a patient was included into the worse DDI category. The detailed information on prescribed medications for this analysis is included in Supplementary Table 2.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics, comorbidities and comedication profiles were reported cross-sectionally in 2018. The descriptive analysis of patient characteristics and health outcomes was summarized using means and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and using counts and percentages for ordinal and nominal variables. The chi-square test was used to compare between groups and each DDI across the three DAA regimens. All data analyses were performed using SAS® Enterprise Guide software version 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was assessed at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population

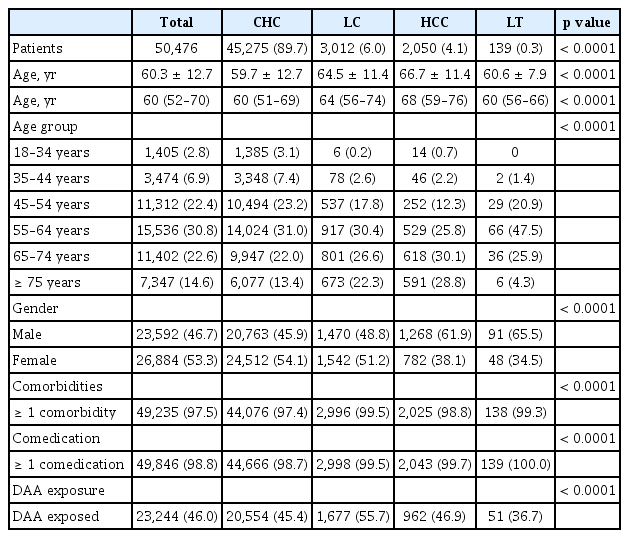

A total of 50,476 patients were identified as CHC in 2018. The mean age (± SD) was 60.3 ± 12.7 years and 37.2% of the patients were more than 65 years old. When the patients were divided into four subgroups, those with CHC, LC, HCC, and LT were 89.7%, 6.0%, 4.1%, and 0.3%, respectively. The mean ages of each subgroup showed significant differences from each other. The mean ages of CHC, LC, and HCC group was 59.7, 64.5, and 66.7 years, respectively (p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

When investigating the status of comorbidities, almost all patients (97.5%) had one or more co-morbidities. The proportion of patients with one or more comorbidities was 97.4% in CHC group, 98.8% in HCC group, and 99.3% in LT group (p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

When investigating the status of comedications, almost all patients (98.8%) had one or more comedications. The proportion of patients with one or more comedications was 98.7% in CHC group, 99.7% in HCC group, and 100.0% in LT group (p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

Of the total patients, 46.0% had DAA exposure, with the LC group having the highest proportion of patients with DAA exposure (55.7%) compared to other subgroups, followed by HCC (46.9%), CHC (45.4%), and LT (36.7%) (p < 0.0001) (Table 1).

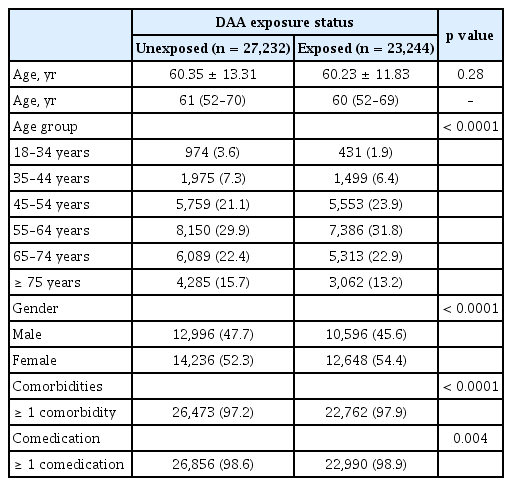

Comparison between DAA-exposed and DAA-unexposed group

The mean age of DAA-exposed patients and DAA-unexposed patients was 60.23 ± 11.83 years and 60.35 ± 13.31 years (p = 0.28), respectively. The proportion of DAA-exposed patients was higher in the age groups of 45–54 years (23.9% vs. 21.1%), 55–64 years (31.8% vs. 29.9%), and 65–74 years (22.9% vs. 22.4%) (p < 0.0001) (Table 2). There were more male patients in the DAA-unexposed group (47.7%) than in the DAA-exposed group (45.6%) (p < 0.0001). The proportions of patients with comorbidities (97.9% vs. 97.2%) (p < 0.0001) and comedications (98.9% vs. 98.6%) (p = 0.004) were higher in the DAA-exposed group as compared with DAA-unexposed group (Table 2).

Comorbidity profiles of the study population

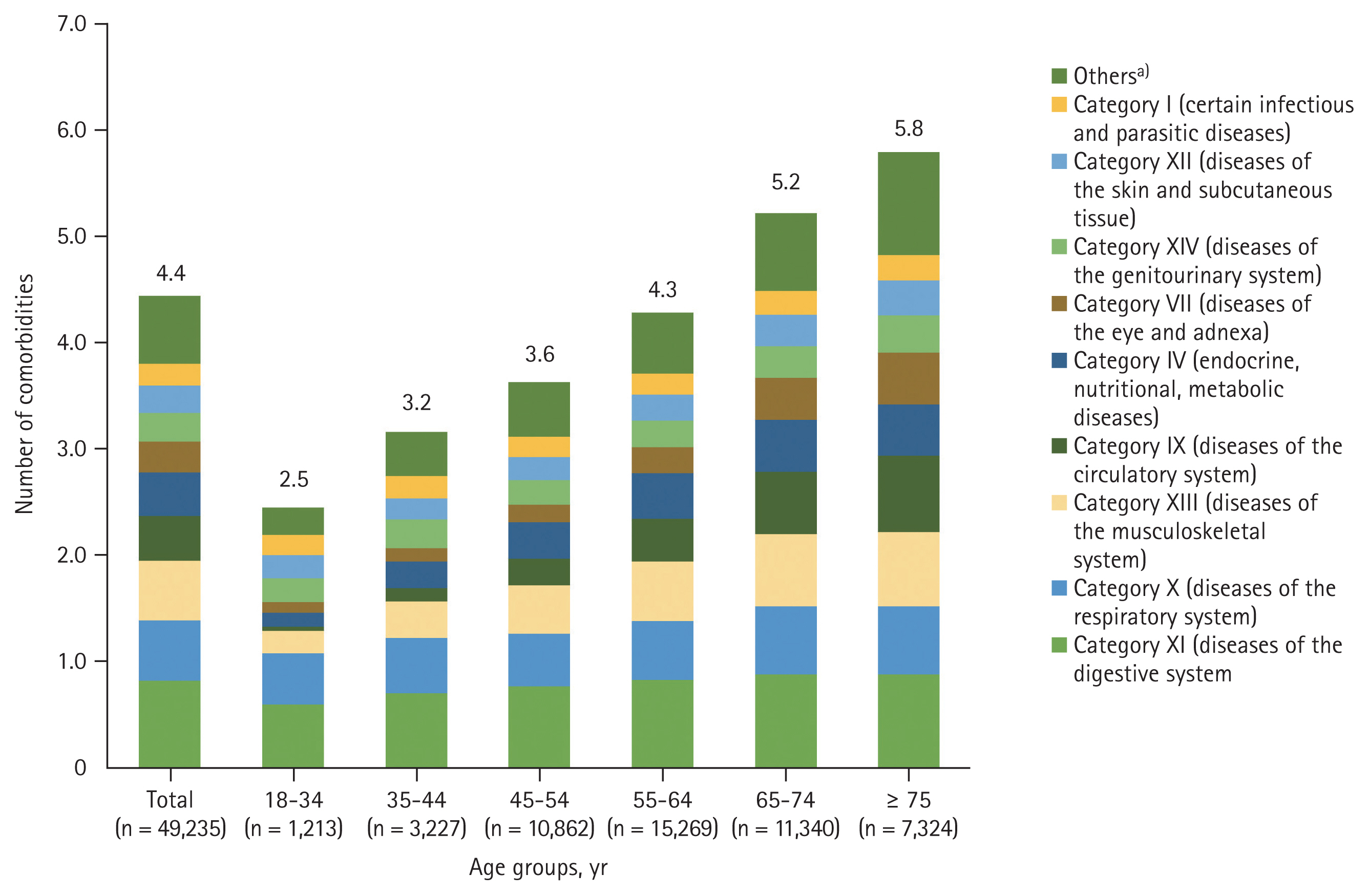

The mean number of comorbidities by disease categories was 4.4 (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 3). The proportion of patients with comorbidities increased with age and the patients aged ≥ 75 years had the highest number of comorbidities. The mean number of comorbidities by disease category was higher in females (4.7) than males (4.2), and in patients with cirrhosis (4.8 vs. without cirrhosis: 4.4) (Supplementary Table 3).

Distribution of chronic hepatitis C patients in Korea with ≥ 1 comorbidities based on age and disease categories. a)Include the following disease categories: category V (mental and behavioral disorders); category VI (diseases of the nervous system); category II (neoplasms); category VIII (diseases of the ear and mastoid processes); and category III (diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism).

The top three most prevalent disease categories include diseases of the digestive system (83.7%), the respiratory system (58.2%), and the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (57.6%) (Supplementary Table 3). Diseases of the respiratory system (category X), diseases of the musculoskeletal system (category XIII), and diseases of the circulatory system (category IX) were observed to have greater increase with age, albeit not significant (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 3). When looking into the KCD-7 disease diagnostic codes, hypertension (34.1%), dyslipidemia (21.5%), diabetes mellitus (19.9%), peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal ulcer (7.9%), and ischemic heart diseases (6.2%) were the most prevalent diseases in patients with CHC (Supplementary Table 4).

The prevalence of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal ulcer was significantly higher in the DAA-exposed groups than in the DAA-unexposed group (p < 0.0001). However, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart diseases were more prevalent in the DAA-unexposed group (p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 4).

Prescribed concurrent medication profiles/patterns of CHC patients

The mean number of comedications in overall patients was 9.5 and the number of comedications increased with age, from 6.2 in younger age group (18–34 years) to 11.3 in older age group (≥ 75 years) (Fig. 2). Female patients (9.7 vs. males: 9.2) and patients with cirrhosis (10.9 vs. without cirrhosis: 9.4) had a higher number of prescribed comedications (Supplementary Table 5).

Distribution of chronic hepatitis C patients in Korea with ≥ 1 comedications based on age and comedication categories. a)Include comedications of anaesthetics, muscle relaxants; antifungals; anticonvulsants; bisphosphonates; hepatitis drugs; parkinsonism agents; antipsychotics, neuroleptics; antivirals; antiprotozoals; cytotoxics; contraceptives and hormonal replacements; immunosuppressants; antimigraine agents; oxytocics; human immunodeficiency virus drugs; and anthelmintics.

The commonly prescribed medications (> 50%) were analgesics (91.6%), gastrointestinal agents (85.0%), anti-bacterials (80.3%), antihistamines (73.5%), anticoagulant, antiplatelet, and fibrinolytics (62.2%), and steroids (58.5%) (Supplementary Table 5).

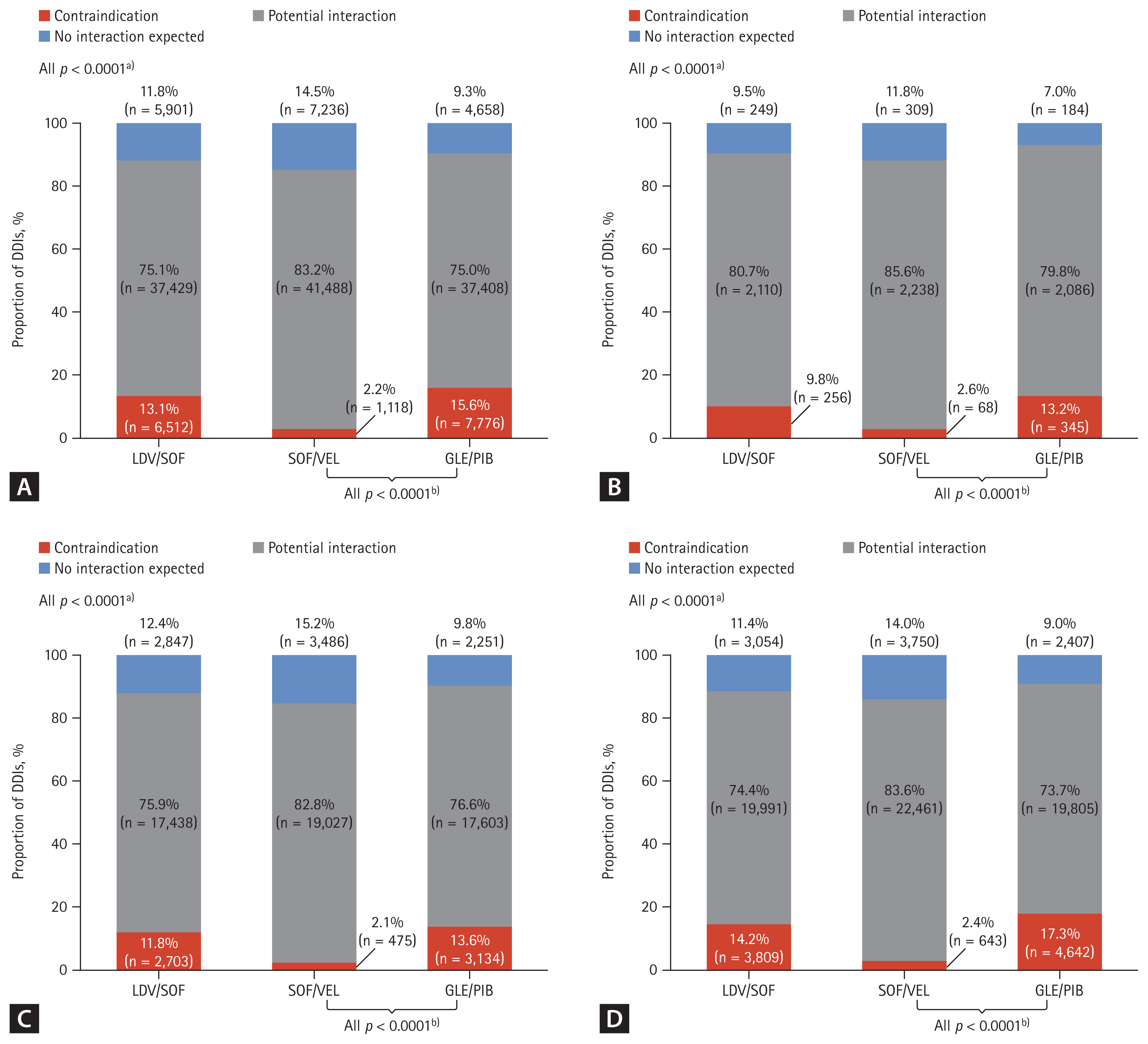

Potential DDIs associated with DAA regimens

The proportion of contraindicated DDIs among CHC patients across the three DAA regimens was lowest in SOF/VEL (2.2%), followed by LDV/SOF (13.1%), and GLE/PIB (15.6%) (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A). SOF-containing regimens (SOF/VEL, LDV/SOF) had lower contraindicated DDI risk compared to GLE/PIB, respectively (Fig. 3A).

The proportion of potential drug-drug interaction (DDI) types with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen by health conditions in hepatitis C virus (HCV) infected patients. (A) Proportion of DDIs reported among all HCV diagnosed patients. (B) Proportion of DDIs reported among HCV diagnosed patients with cirrhosis. (C) Proportion of DDIs reported among all HCV diagnosed patients in the DAA exposed group. (D) Proportion of DDIs reported among all HCV diagnosed patients in the DAA unexposed group. DDI were categorized as ‘Contraindication’ from reference of Liverpool University and Pecking University. LDV, ledipasvir; SOF, sofosbuvir; VEL, velpatasvir; GLE, glecaprevir; PIB, pibrentasvir. a)p values indicated for each potential DDIs (contraindication; potential interaction; no interaction expected) across each DAA regimen (LDV/SOF vs. SOF/VEL vs. GLE/PIB). b)p values indicated for potential DDIs (contraindication; potential interaction; no interaction expected) across each DAA regimen (SOF/VEL vs. GLE/PIB).

The proportion of no interaction expected was lowest in GLE/PIB (9.3%), followed by LDV/SOF (11.8%), and SOF/VEL (14.5%) (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A). Similar trends were observed in patients with cirrhosis and in the DAA-exposed group as well as when compared in age groups (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 3B-D, Supplementary Table 6).

Of all contraindications when classified by drug classes, the HIV drug class with GLE/PIB had the greatest number of prescribed comedications with contraindications, followed by anticonvulsants with all three DAA regimens (Supplementary Fig. 1). The three most common comedications which were classified as “contraindication” were atorvastatin with GLE/PIB (12.7%), rosuvastatin with LDV/SOF (11.1%), and simvastatin with GLE/PIB (1.4%) (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to investigate the demographics, comorbidities, and comedication profiles of patients with CHC in Korea using the nationwide claims database of 2018, and to identify any potential DDIs with the latest DAA regimens. Herein, our study found that the mean age of Korean patients with CHC was 60 years in 2018 with 37.2% of patients over the age of 65. This demonstrates the high disease burden in the elderly population with CHC in Korea, enforcing the importance of treating HCV infection at the earliest to prevent complications [16]. In a previous study including nationwide Korean CHC patients, the mean age was around 57. This suggests an aging trend in Korean patients with HCV wherein, risk factors associated with aging should be taken into consideration when treating CHC patients of older age [17].

In this study, nearly all identified CHC patients had comorbidities (97.5%) and comedications (97.5%). The previous study of CHC patients from another national data base of 2013 showed that 84.8% of CHC patients had comorbidities and 96.8% of patients with comedications [8]. Since this study implemented the similar inclusion and exclusion criteria for patient selection from the previous study [8], as well as methods of counting comorbidity and comedications, one can assume that the proportions of CHC patients with comorbidities and comedications have relatively increased. This could be associated with the high proportion of elderly patients aged ≥ 55 years recorded in this study (n = 34,285), wherein the elderly patients would have higher underlying comorbidities than younger patients [18].

When looking into comorbidities by disease code, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes are the most prevalent among CHC patients regardless of age group. As these are chronic metabolic diseases that require continued monitoring and treatment, this finding also highlighted the importance of considering comorbidities and comedications when initiating DAA treatment in patients with CHC.

It is interesting to see that SOF-containing regimens (SOF/VEL, LDV/SOF) had lower contraindicated DDI risk compared to GLE/PIB, respectively. This is aligned with another previous study [10,19], where a real-world observational Italian study reported that contraindications due to DDIs remained higher in GLE/PIB cohorts both before (9.3%) and during DAA treatment (3.2%), while patients with contraindicated co-treatments decreased from 3.2% to 0.4% after SOF/VEL initiation [10]. Similar observations were highlighted in the Taiwanese study. In this study, a total of 86.3% of hepatitis C patients had ≥ 1 comorbidity and 75.7% of patients received ≥ 1 concomitant medication [19]. The study demonstrated a high prevalence of comorbidities and widespread use of concomitant medications [19]. Among patients without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, contraindications were more prevalent with PTV/ritonavir/OBV plus DSV (13.3%), DCV/ASV (6.0%) and GLE/PIB (5.4%) compared with SOF-based regimens (0.8–2.1%). SOF-based regimens had no contraindications in patients with decompensated cirrhosis [19].

There are a few limitations to the study. The study had investigated potential DDIs by collecting all the comedications for the patients with CHC diagnosis but not actual DDIs linked to individual patients. Furthermore, the study was conducted based on the national claims database, which is more focused on prescribed medications. There can be additional medications such as over-the-counter medications that the patients are taking without prescriptions. Due to the nature of administrative data, errors or omissions of diagnostic codes could exist. Considering the nature of the claims data and the National health care system in Korea, this HIRA data represents characteristics of the HCV patients diagnosed in Korea. Since the previous research from Chung et al. [8], utilized the 2013 NHIS (National Health Insurance System) data and the HIRA data was used to identify patients recorded in 2018, we could not have a direct comparison between the two data sets. Although we were not able to make a direct comparison of the 2013 NHIS data to the 2018 HIRA data, the HIRA data well represents the prescription pattern nationwide as we investigated the changing trends of CHC patients in Korea. Therefore, this study holds value in providing an aging trend of patients with HCV as well as an increase in the comorbidity and comedication patterns in such patients. This study also reports the latest potential DDI in patients with HCV which can be taken into consideration by physicians when initiating treatment with DAAs in patients with chronic HCV infection.

Overall, the study findings highlighted that there was a trend toward increasing mean age, comorbidity, and comedication of Korean patients with CHC in 2018. This study also provided an update in DDI analyses wherein, newer pangenotypic DAA regimens available since 2013 were included, which can be referenced for practical clinical use.

While DAAs regimens objectively treat HCV infection, consideration of comorbidities and prescribed comedication is essential to minimize the risks of DDIs especially since there is a growing proportion of elderly HCV-diagnosed patients. In this setting, evaluation of comorbidities and comedication is essential to minimize the potential risk of DDIs and choose the safe options with favorable DDI features ahead of treating CHC patients, to improve patient outcomes and optimize patient management.

KEY MESSAGE

1. With the increasing age of chronic hepatitis C patients in Korea, number of comorbidity and comedication is increasing.

2. Drug-drug interaction (DDI) should be considered and consulted prior to hepatitis C virus treatment.

3. In general, sofosbuvir-based regimen has lower DDI in Korean patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Amanda Woo and Ms. Sandhya Kaimal from Cerner Enviza for providing medical writing and editorial support.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Kyung Min Kwon: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, writing - review & editing; Jae-Jun Shim: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing - review & editing; Gi-Ae Kim: conceptualization, writing - review & editing; Bo Ok Kim: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing - review & editing; Helin Han: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing - review & editing; Hyun Jung Ahn: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, visualization, writing - review & editing

Conflicts of interest

Kyung Min Kwon is an employee of Gilead Sciences. Jae-Jun Shim is an employee of the Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea, and Cheorwon Hospital, Gangwon-do, Korea. Gi-Ae Kim is an employee of the Department of Internal Medicine, Kyung Hee University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea. Bo Ok Kim, Helin Han, and Hyun Jung Ahn are employees of Cerner Enviza.

Funding

This study was funded by Gilead Sciences. Cerner Enviza received funding for the conduct of the study and development of the manuscript.