INTRODUCTION

Secondary leukemia or de novo leukemia should be considered when a new leukemia develops after successful treatment of various malignancies. Secondary leukemia refers to the appearance of a new, biologically-unrelated leukemia different from the primary malignancy, following the treatment of the primary malignancy; de novo leukemia refers to leukemia in patients without exposure to potentially leukemogenic therapies or agents. In patients that undergo allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), the possibility of the appearance of leukemia from allogeneic hematopoiesis (donor cell leukemia) as well as de novo or secondary leukemia, which originates in the recipient, should also be considered despite lower likelihood and difficulty to confirm. It is not surprising that a large percentage of patients who develop secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) were previously treated for hematological disorders but not solid tumors, considering the responsiveness of hematologic malignancies to chemotherapy [1]. However, in most cases, prior treatment was not for leukemia but for lymphoma and myeloma [2,3]. Indeed, although malignancies after HSCT has been well documented [4], secondary leukemia occurring after HSCT for AML is rare [5,6]. In addition, most reports of secondary AML follow autologous transplantation, and it is rare following allogeneic transplantation regardless of the primary disease [4], primarily because the anti-leukemic effects of the allogeneic graft reduce the risk of a secondary clone developing.

We present a case initially diagnosed as a de novo AML without a cytogenetic abnormality. The patient was successfully treated with a HLA-matched sibling allogeneic HSCT. However, more than six years later, a second AML developed that was associated with new complex cytogenetic abnormalities.

CASE REPORT

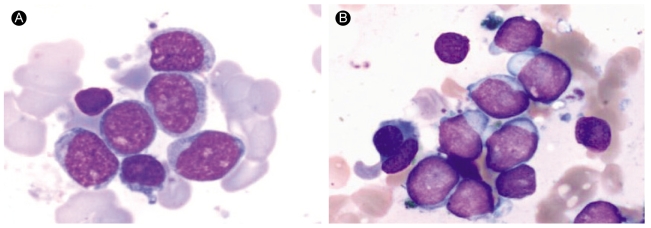

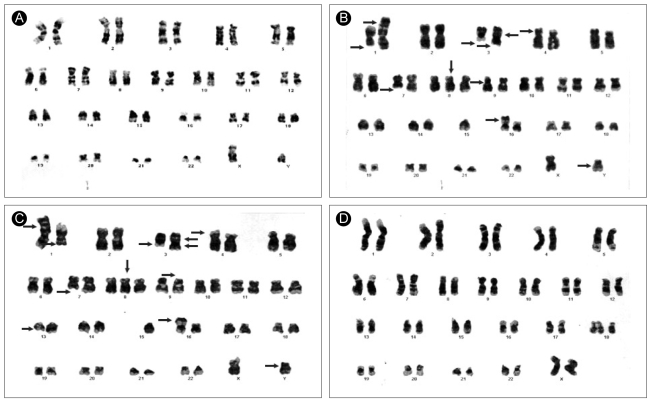

A 36-year-old man was diagnosed with AML-M1 by the FAB classification in April 1998 (Fig. 1A). His chromosome analysis showed a 46, XY karyotype without any cytogenetic abnormalities (Fig. 2A). He was treated with induction chemotherapy (idarubicin 12 mg/m2/d on days 1 to 3, enocitabine 300 mg/m2/d on days 1 to 7, 6-thioguanine 100 mg/m2, bid on days 1 to 7) and augmentation chemotherapy (enocitabine 400 mg/m2/d for 2 days). He achieved a complete remission, and underwent consolidation chemotherapy with amsacrine 100 mg/m2/d on days 1 to 3 and etoposide 100 mg/m2/d on days 1 to 5. The patient had two HLA-identical sisters out of his three siblings, and received an allogeneic bone marrow (BM) HSCT from one of his fully matched sisters on December 1998; conditioning included fractionated total body irradiation (TBI) 1200 cGy for three days, followed by cyclophosphamide 120 mg/m2 for two days. On day 21, a BM biopsy revealed morphologically stable engraftment with definite three-lineage maturation. The first HSCT resulted in a continuous, complete remission that lasted seventy three months. On December 2004, he presented with a hemoglobin of 9.1 g/dL, white blood cells 2.0 × 109/L and platelets 52 × 109/L. A BM aspirate showed that a majority of the nucleated elements were blasts without dysplastic changes (Fig. 1B). Cytogenetic analysis showed a complex karyotype: 46,X, der(Y)t(Y;15)(q11.2;q11.2), del(1)(q32), t(1;3)(p36.1;q21),inv(3)(p21q25),add(4)(p16), del(7)(q22),+8,inv(9)(p13p24),-15,add(16)(p13.3)[8]/46,idem,del(13)(q12q22)[3]/46,XX[9](Fig. 2B). Molecular analysis with a Y-chromosome probe revealed that the abnormal chromosomes originated from the recipient. The patient achieved morphological and cytogenetic remission again with reinduction chemotherapy; he underwent a second allogeneic peripheral blood HSCT from another human leukocyte antigen-identical sister on May 2005. Stable engraftment and normal peripheral blood counts were achieved. The patient has been followed for over 12 months after the second HSCT without serious complications.

DISCUSSION

This case is characterized by a longer latency period than in previous reports of secondary AML following hematologic and/or non hematologic malignancies [2,3] as well as rare cases of secondary AML following de novo AML [5,6], in the setting of an allograft. In our case, the new complex cytogenetic aberrations, as well as the allograft setting, suggested that the origin of the second AML might be biologically unrelated to the first. There are two possible origins for the second AML: a secondary AML, another de novo AML, or perhaps a donor cell leukemia.

Secondary AML is primarily associated with therapy-related myelodysplasia and/or therapy-related AML (t-AML) as a late complication following cytotoxic therapy [1-3,5,6]. t-AML consists of 2 different syndromes: one with a long latency (5 to 7 years or more) observed following the administration of alkylating agents, which frequently show antecedent dysplastic changes and clonal abnormalities with loss of all or part of chromosome 5 or 7, or both. The other syndrome has a short latency period (1 to 3 years), with no antecedent dysplastic phase, abnormalities of chromosome 11, specifically 11q23, or abnormalities of chromosome 21q22, and usually follows the use of topoisomerase II inhibitors [1]. Our patient received topoisomerase II inhibitors for induction (idarubicin) and consolidation (amsacrine and etoposide) chemotherapy, and the alkylating agents, TBI/cyclophosphamide, for conditioning therapy. In our case, the long latency period and cytogenetic abnormalities characterized by deletion of 7q would suggest that the newly developed AML might be a t-AML caused by cyclophosphamide and/or TBI, rather than by topoisomerase II inhibitors. However, the dose of cyclophosphamide was much lower than normally associated with t-AML [7], there were no antecedent dysplastic changes and relatively long latency period, and secondary AML is very rare in the allograft setting [4], making it difficult to verify this possibility.

Another possibility is the development of another primary AML, either de novo AML or donor cell leukemia. However, donor cell leukemia was excluded by cytogenetic studies showing the aberrations associated with a Y chromosome. Then, is the second de novo AML of recipient origin? First, our case had a longer latent period and an allogeneic HSCT. Generally, in all grafted adult AML, patients without a relapse or chronic graft-versus-host disease five years after allogeneic HSCT are often considered "cured". Second, deletion of 7q, which may be associated with alkylating agents, often occurs in de novo AML as well as secondary AML [8]. Third, considering the possible graft-versus-leukemia effect of the allograft, our patient was probably cured and then developed a new AML later. Finally, the patient showed a good clinical course after the second allogeneic HSCT; secondary AML due to alkylating agents has a uniformly poor prognosis [1]. Alternatively, the clones found in the second AML may have been undetected subclones at the time of the first AML that later gained proliferative potential after the HSCT. However, this is unlikely and would be difficult to prove even with molecular genetic analysis [5].

In conclusion, our patient may have had a second de novo AML following successful treatment of the first de novo AML, although we could not rule out other possibilities. Future studies of a patient's intrinsic genetic makeup may help indicate a predisposition to the rare development of a secondary or de novo AML.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print