|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 29(3); 2014 > Article |

|

Abstract

Acute esophageal necrosis is uncommon in the literature. Its etiology is unknown, although cardiovascular disease, hemodynamic compromise, gastric outlet obstruction, alcohol ingestion, hypoxemia, hypercoagulable state, infection, and trauma have all been suggested as possible causes. A 67-year-old female underwent a coronary angiography (CAG) for evaluation of chest pain. CAG findings showed coronary three-vessel disease. We planned percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Coronary arterial dissection during the PCI led to sudden hypotension. Six hours after the index procedure, the patient experienced a large amount of hematemesis. Emergency gastrofibroscopy was performed and showed mucosal necrosis with a huge adherent blood clot in the esophagus. After conservative treatment for 3 months, the esophageal lesion was completely improved. She was diagnosed with acute esophageal necrosis. We report herein a case of acute esophageal necrosis occurring in a patient undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Acute esophageal necrosis is a rare condition. Its etiology is unknown, although cardiovascular disease, hemodynamic compromise, gastric outlet obstruction, alcohol ingestion, hypoxemia, hypercoagulable state, infection, and trauma have been suggested as possible causes [1]. We report here a case, and we include a literature review.

A 67-year-old female presented to an outside hospital with exertional chest pain associated with diaphoresis and dyspnea. She had no previous history of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, or cigarette smoking. Cardiac enzyme levels were within normal limits. Electrocardiography showed normal sinus rhythm. The treadmill test showed a positive finding. We planned an elective coronary angiography (CAG) to establish a confirmative diagnosis.

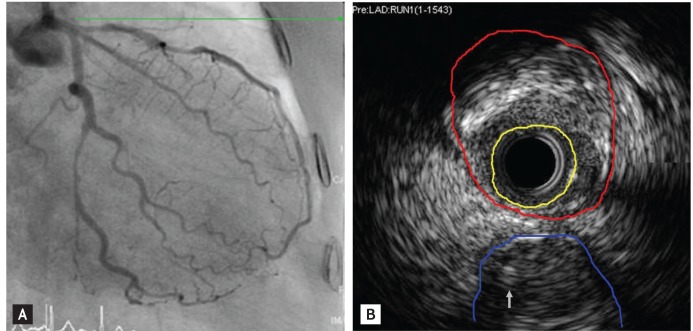

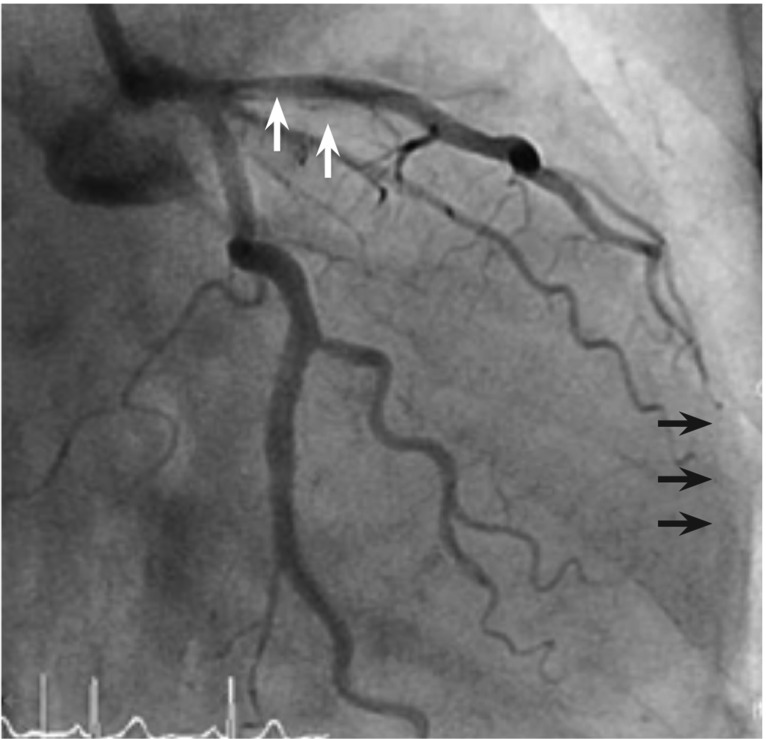

CAG findings showed visually a 80% to 90% diffuse stenosis in the distal left circumflex artery (LCx), a 70% to 80% tandem stenosis in the proximal and mid left anterior descending artery (LAD) (Fig. 1A), and a 50% to 60% diffuse stenosis in the mid right coronary artery (RCA). Intravascular ultrasound revealed that the minimal luminal area was 2.25 mm2 and external elastic membrane cross sectional area was 13.5 mm2 at the ostium. The proximal LAD stenotic lesion consisted of mixed plaque. Therefore, the stenotic area was approximately 83.5% (Fig. 1B). We planned percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for the distal LCx and proximal/mid LAD and medical treatment for the mid-RCA. PCI for the distal LCx and mid-LAD was successful. However, shortly after balloon inflation for the proximal LAD, the patient complained of severe chest pain, and then her blood pressure abruptly fell to 70/40 mmHg. Cineangiography showed major dissection in the proximal LAD and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade I to II (Fig. 2). We made an immediate stent deployment by the cross-over technique to the proximal LAD from the left main coronary artery. Nitroglycerin and adenosine were infused simultaneously via the intracoronary arterial route. After approximately 20 minutes, her vital signs returned to normal and her chest pain subsided. We successfully completed the procedure. She was transferred to the coronary care unit for close observation.

Six hours after the index procedure, the patient experienced a large amount of hematemesis. Emergency gastrofibroscopy (GFS) was performed to determine the cause of the sudden hematemesis. Upper endoscopy showed black macerated mucosa in the mid third of the esophagus and circumferential mucosal necrosis with a huge adherent blood clot in the distal third of the esophagus (Fig. 3A and 3B). She was diagnosed with acute esophageal necrosis, based on the GFS finding and her past history that did not include alcohol consumption, liver disease, varices, peptic ulcer disease, abdominal aortic surgery, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, gastroparesis, or previous gastrointestinal bleeding. She was started on pantoprazole (40 mg, twice daily) and continued on aspirin, clopidogrel, and atorvastatin. She was discharged on hospital day 7. One (Fig. 3C) and three (Fig. 3D) months after the event, follow-up upper endoscopy revealed complete resolution of the esophageal lesion.

Black esophagus, also known as acute necrotizing esophagitis or acute esophageal necrosis, was first described by Goldenberg et al. [2] in 1990. Six cases of black esophagus were seen at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester from 1997 through 2003, and 46 cases were reported in the English-language literature from 1963 through 2003 [3]. Moreto et al. [4] identified 10 cases of acute esophageal necrosis in a review of more than 80,000 upper endoscopies, with an incidence of only 0.0125%. Grudell et al. [3] suggested that ischemia is the most common cause of black esophagus. Gurvits et al. [5] demonstrated that the major risk factors include histories of cardiovascular disease, hemodynamic compromise including shock, and severe third spacing. Neumann et al. [6] reported a case of black esophagus associated with hypotension that developed during an acute coronary event. Also, he reported that endoscopically, the lesion often appears circumferential and black, with friable or macerated mucosa, usually involving the distal two thirds of the esophagus. Histopathology usually shows necrotic debris and mucosal and submucosal necrosis with a local inflammatory response [5]. The esophagus receives an intricate segmental vascular supply that separates this organ into three parts: upper, middle, and distal esophagus. The arterial network of the upper esophagus is derived from the descending branches of the inferior thyroid arteries. The mid-esophageal blood supply is derived from the bronchial arteries, right third or fourth intercostal arteries, and numerous small esophageal arteries off the descending aorta. The distal esophagus receives its blood flow from branches off the left gastric artery or left inferior phrenic artery, but variations are common [7]. Therefore, since the esophagus has a rich intramural arteriovenous network complementing the segmental blood flow, spontaneous esophageal ischemia followed by necrosis is rare [8]. The overall mortality of acute esophageal necrosis reported in the largest case review to date was high (32%) [4]. Mortality was most frequently secondary to the seriousness of the comorbid disease state. Our patient had no severe comorbidities except for the underlying coronary three-vessel disease, and the esophageal lesion improved with only conservative treatment using an oral proton-pump inhibitor. Coronary arterial dissection associated with therapeutic coronary intervention occurs in approximately 32% to 41% of cases [9]. In our case, coronary arterial dissection during the PCI led to sudden hypotension, which was suspected to cause acute esophageal ischemia and then necrosis. Interventional cardiologists should be aware that not only acute coronary events or chronic cardiovascular diseases but also acute hemodynamic changes that can take place during coronary intervention may cause acute esophageal necrosis.

References

1. Lacy BE, Toor A, Bensen SP, Rothstein RI, Maheshwari Y. Acute esophageal necrosis: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:527ŌĆō532PMID : 10202074.

2. Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology 1990;98:493ŌĆō496PMID : 2295407.

3. Grudell AB, Mueller PS, Viggiano TR. Black esophagus: report of six cases and review of the literature, 1963-2003. Dis Esophagus 2006;19:105ŌĆō110PMID : 16643179.

4. Moret├│ M, Ojembarrena E, Zaballa M, Tanago JG, Ibanez S. Idiopathic acute esophageal necrosis: not necessarily a terminal event. Endoscopy 1993;25:534ŌĆō538PMID : 8287816.

5. Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007;42:29ŌĆō38PMID : 17322991.

6. Neumann DA 2nd, Francis DL, Baron TH. Proximal black esophagus: a case report and review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;70:180ŌĆō181PMID : 19152880.

7. Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:3219ŌĆō3225PMID : 20614476.

8. Watanabe S, Nagashima R, Shimazaki Y, et al. Esophageal necrosis and bleeding gastric ulcer secondary to ruptured thoracic aortic aneurysm. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;50:847ŌĆō849PMID : 10570351.

9. Lim SY, Jeong MH, Kim W, et al. A case of spiral dissection during diagnostic coronary angiography. Korean J Med 2003;65:361ŌĆō364.

Figure┬Ā1

(A) Initial coronary arteriography shows a 70% to 80% diffuse stenosis in the mid left circumflex artery and a 70% to 80% tandem stenosis in the proximal and mid left anterior descending artery. (B) Intracoronary ultrasound revealed that the minimal luminal area (yellow line) was 2.25 mm2 and the external elastic membrane cross sectional area (red line) was 13.5 mm2 at the ostium. The proximal left anterior descending artery stenotic lesion consisted of mixed plaque. Therefore, the stenotic area was approximately 83.5%. A left circumflex artery (blue line) and a wire (arrow) are shown.

Figure┬Ā2

After balloon dilatation, a major dissection occurred in the proximal left anterior descending artery (white arrows), which induced thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade I to II in the distal left anterior descending artery (black arrows).

Figure┬Ā3

Serial follow-up endoscopic findings. The initial endoscopy shows (A) black macerated mucosa (arrows) in the mid third of the esophagus and (B) circumferential mucosal necrosis (arrowheads) with a huge adherent blood clot in the distal third of the esophagus. (C) After 1 month, detachment of the necrotic mucosa with re-epithelialization was noted at the same site. (D) Follow-up endoscopy performed 3 months after the first session shows completely healed esophageal mucosa without evidence of ischemic complications.

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

Late diagnosis of influenza in adult patients during a seasonal outbreak2018 March;33(2)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print