|

|

| Korean J Intern Med > Volume 38(5); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Background/Aims

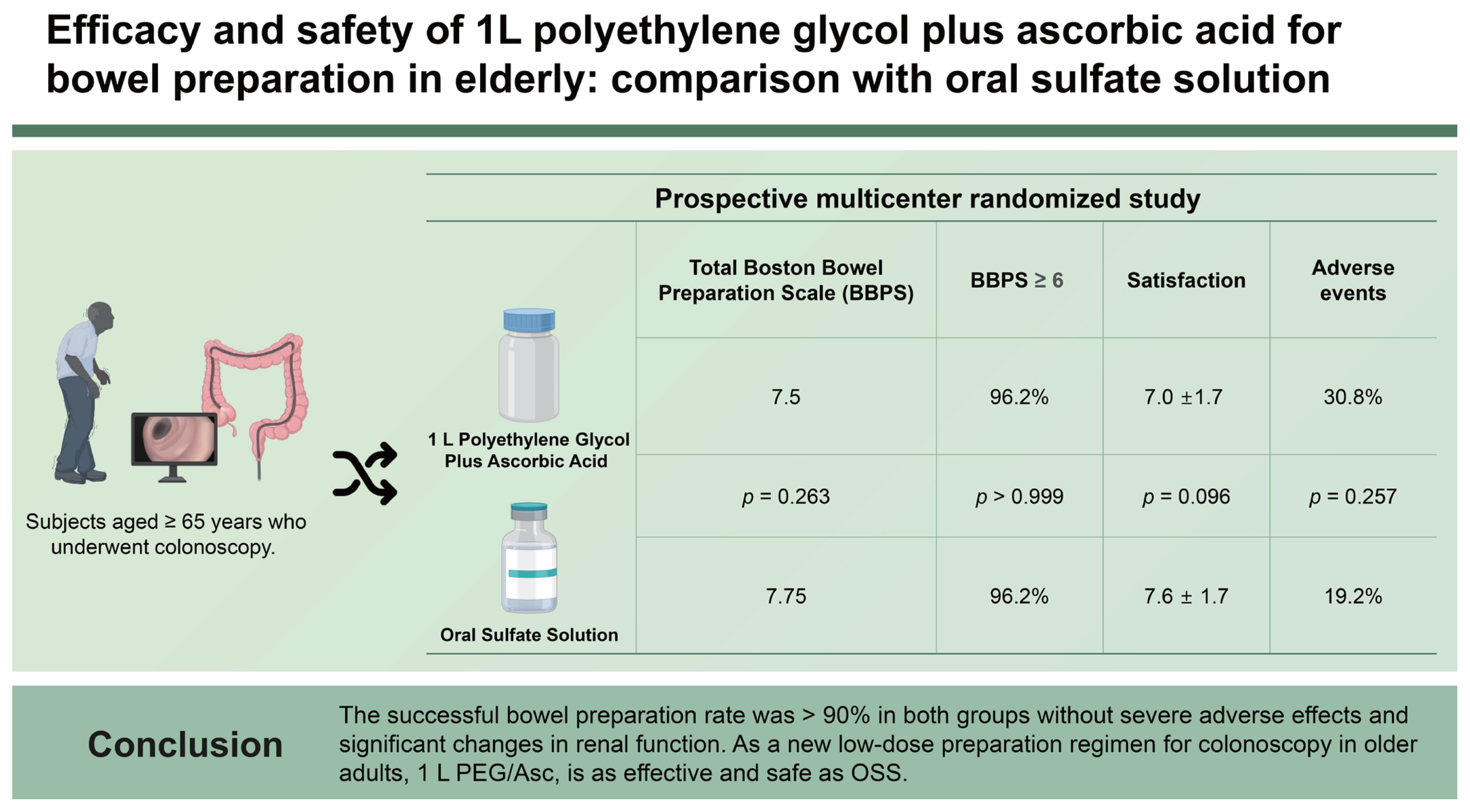

Recently, 1 L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) plus ascorbic acid (Asc) has been introduced in Korea as a colonoscopy preparation agent. Data on its efficacy and safety in older adults have been limited. We aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of 1 L PEG/Asc in older adults by comparing it with oral sulfate solution (OSS).

Methods

A prospective multicenter randomized study was conducted with subjects aged Ōēź 65 years who underwent colonoscopy. The participants were randomized to receive 1 L PEG/Asc or OSS. The primary endpoint was successful bowel preparation, defined as total Boston Bowel Preparation Scale Ōēź 6, and Ōēź 2 at each segment. Patient satisfaction, adverse events, and renal function changes were compared between the groups.

Results

Among the 106 patients, 104 were finally included in the analysis. Overall, successful bowel preparation was achieved in 96.2% of both 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS groups. The satisfaction scores for taste, total amount ingested, overall feeling, and willingness to repeat the same regimen were not significantly different between the groups. Adverse events of moderate or higher severity occurred in 16 and 10 cases in the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS group, respectively. There were no significant changes in electrolyte levels or renal function from baseline.

Colonoscopy with removal of premalignant lesions has been considered the most effective colorectal cancer (CRC) screening tool because most CRCs arise from adenomatous polyps [1,2]. Considering that the incidence of colorectal adenoma and cancer increases with age, a large proportion of colonoscopies are performed on older adults [3]. Although adequate bowel preparation is crucial for a full inspection of the colonic mucosa and removal of precancerous lesions, older adults are at higher risk of poor bowel preparation due to slower colonic transit and higher prevalence of obstipation [4]. In addition, they are less tolerant to large-volume preparation agents than younger patients [5]. Various low-volume preparation agents, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) and non-PEG-based agents, have been introduced to enhance tolerability and adherence. Most of the agents have proven to be non-inferior in efficacy and safety compared with 4 L PEG [6ŌĆō13]. However, most studies regarding novel low-volume preparation agents have excluded older adults. Therefore, the 4 L PEG-based split dose preparation is still accepted as safe and effective in these age groups despite reduced adherence due to the large volume [14]. Considering that older adults are at higher risk of colorectal neoplasms and have low tolerability to ingest large volumes of preparation agents, it could be very helpful if low-volume preparation is effective and safe for them.

Recently, 1 L PEG plus ascorbic acid (1 L PEG/Asc) was introduced in Korea. Although its efficacy and safety have been approved by several studies, data on older adults have been limited. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of 1 L PEG/Asc in older adults by comparing it with another non-PEG-based low-volume preparation, oral sulfate solution (OSS).

This prospective, randomized, non-inferiority, investigator-blinded, multicenter study was conducted at five academic hospitals in Korea from September 2019 to August 2020. Eligible patients were consecutive older adult outpatients aged between 65 and 84 years who had undergone screening or surveillance colonoscopy for colon polyp and CRC. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) previous history of colectomy or gastrectomy; (2) inflammatory bowel disease; (3) severe constipation; (4) intestinal obstruction; (5) severe congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association [NYHA] class III or IV); (6) acute myocardial infarction in the preceding six months; (7) severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance rate < 30 mL/min); (8) liver cirrhosis; and (9) American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status index Ōēź III.

Participants who provided informed consent in each hospital were randomly assigned to receive computer-generated random numbers into 1 L PEG/Asc or OSS groups at a 1:1 ratio. The investigators did not know which regimen was assigned to the participants until study completion.

Patients were 1:1 randomized to receive the bowel cleansing regimens: (1) 1 L PEG/Asc (CleanViewAL; Taejoon Pharm, Seoul, Korea; composition: PEG 3350, 160 g; sodium chloride, 2.7 g; potassium chloride, 1.0 g; anhydrous sodium sulfate, 18 g; Acs, 40.6 g; and sodium ascorbate, 9.4 g) and (2) OSS (Suprep; Taejoon Pharm; composition: sodium sulfate, 35 g; potassium sulfate, 6.26 g; magnesium sulfate, 3.2 g).

All enrolled participants were instructed by a nurse to consume a low-fiber diet three days before colonoscopy, and a rice porridge at 5 p.m. the day before the examination. The preparations were dispensed by a nurse who carefully explained how they should be taken, emphasizing the importance of complete intake of the solution to ensure a safe and effective procedure.

All preparations were performed using a split dose. The first and second dose were administered between 6:00 and 8:00 p.m. on the day before the colonoscopy and 6:00 and 8:00 a.m. on the day of the colonoscopy, respectively. Patients in the 1 L PEG/Asc group drank 500 mL of Clean-ViewAL solution, with an additional 500 mL of plain water in the evening before the colonoscopy. Patients in the OSS group drank 473 mL Suprep solution, which was a mixture of a bottle of Suprep and plain water, followed by the same amount of plain water in the evening before the colonoscopy. The same procedures were repeated with the same agents on the morning of the colonoscopy in both groups. The preparations were completed at least 2 hours prior to the examination, and colonoscopies were performed within 6 hours of the last dose prepared. All patients underwent colonoscopy in the morning between 9:00 a.m. and noon.

The primary endpoint was the successful bowel preparation rate using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS), which was defined as a score Ōēź 2 for each segment and a total score Ōēź 6. Using BBPS, the degree of bowel cleansing was rated on a scoring scale of 0 to 3 for each anatomical segment of the colon (right, transverse, and left segment): 0 (unprepared colon segment with mucosa not seen due to solid stool that could not be cleared); 1 (portion of mucosa of the colon segment seen, but other areas of the colon segment not well seen due to staining, residual stool, and/or opaque liquid); 2 (minor amount of residual staining, small fragments of stool and/or opaque liquid, but mucosa of colon segment seen well); and 3 (entire mucosa of colon segment seen well, with no residual staining, small fragments of stool, or opaque liquid) [15,16]. The other secondary endpoints were perfect bowel preparation rate defined as a score Ōēź 3 for all segments and total score = 9, cecal intubation rate, average withdrawal time, and adenoma detection rate (ADR).

Bowel cleansing and other outcomes were assessed by the endoscopists performing the procedure, each of whom had at least 10 or more years of experience performing colonoscopies, and was unaware of the preparation method. To reduce inter-observer variability, all participating endoscopists were trained with captured colonoscopy sample images before study initiation. The preparation score was assessed by endoscopists as soon as the colonoscopy was completed, and reference images were provided in each case report form for standardized assessment.

On the day of colonoscopy, all participants completed a questionnaire related to tolerability by the study nurse before the procedure. Satisfaction and tolerability in terms of taste, amount, and overall feeling were assessed using a 10-level visual analog scale (VAS). We categorized the scores into five grades: very bad, bad, moderate, good, and very good. If the score was higher than 6, we considered it to be good. Complete ingestion rate and willingness to repeat the same regimen were also assessed.

Any adverse events related to bowel preparation, such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, thirst, sleep disturbance, numbness, general weakness, fecal incontinence, convulsion, change of consciousness, and anuria, were also evaluated by the study nurse before colonoscopy. One adverse event, thirst, was assessed based on the patientŌĆÖs feeling of dry mouth. These symptoms were rated on a 5-point scale (none, mild, moderate, severe, or very severe). In addition, mucosal changes defined as the appearance of aphthous ulcers, ulcers, and erythema in the colonic mucosa due to preparation were compared.

Changes in renal function or serum electrolyte levels before and after preparation were compared between the groups. Blood tests to assess renal function and electrolyte concentrations were performed on the day of colonoscopy immediately after preparation, and compared with the results obtained at the screening visit for the baseline study.

We assumed that successful bowel preparation would be achieved in 90% of the patients in the OSS group based on a previous study [8]. The sample size required for 80% power to detect a 15% difference in successful bowel preparation rate with a two-sided significance level of 0.05 was estimated as 48 in each group. Considering a dropout rate of 10%, a total of 106 patients (53 in each group) were needed to prove the non-inferiority of 1 L PEG/Asc.

Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and rates, while continuous variables are described as mean ┬▒ standard deviation or median (range). Chi-square or FisherŌĆÖs exact tests were used to compare categorical variables, while StudentŌĆÖs t-test was used to compare continuous variables. Statistical significance was identified at a two-sided p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The study protocol was registered at cris.nih.go.kr (KCT0004224), and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Yeungnam University Hospital (YUMC 2019-07-016) and all participating hospitals. The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request by the corresponding author.

A total of 106 patients were randomized to receive either 1 L of PEG/Asc (n = 53) or OSS (n = 53). Of these, one patient in each group withdrew consent and was excluded from the analyses. Accordingly, 52 patients in both groups were included. The baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the groups, with no significant differences. The median age of the patients in 1 L-PEG/Asc and OSS groups was 70.5 ┬▒ 4.5 years (range, 65ŌĆō83 yr) and 70.5 ┬▒ 5.3 years (range, 65ŌĆō84 yr), respectively, and the male-to-female ratio did not significantly differ between groups. Twenty-six patients (25.0%) were aged > 75 years, 11 (21.2%) in the 1 L PEG/Asc group, and 15 (28.8%) in the OSS group. The proportions of patients with comorbidities were 57.3% and 67.3%, respectively (Table 1).

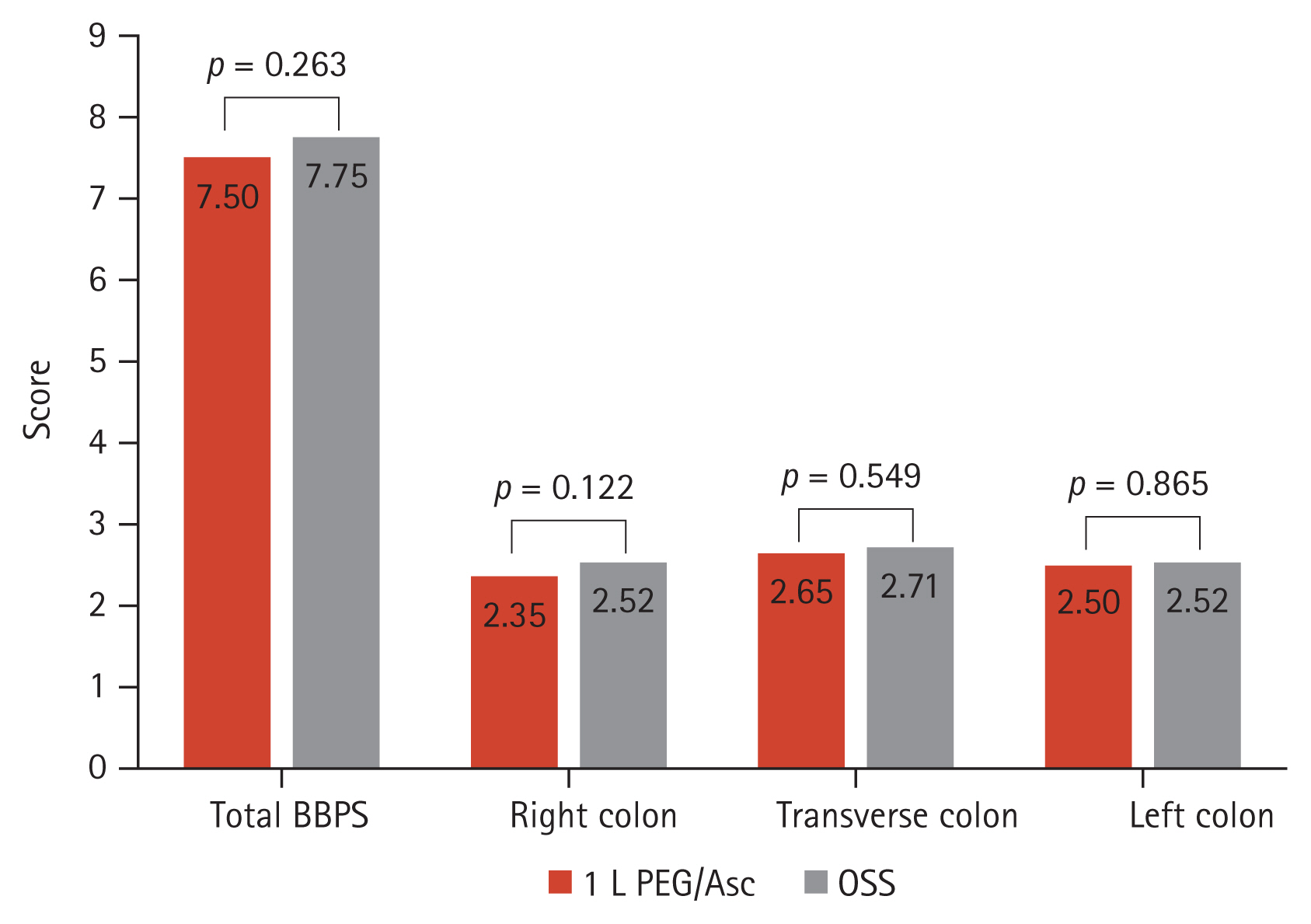

Cecal intubation was achieved in 100% of the 1 L PEG/Asc group versus 98.1% (51/52) of the OSS group (p > 0.999). The withdrawal time did not differ between groups (775.9 ┬▒ 536.9 s vs. 828.5 ┬▒ 506.7 s, p = 0.609). The mean overall BBPS (7.50 ┬▒ 1.1 vs. 7.75 ┬▒ 1.1, p = 0.263), and the mean score at each segment (right, transverse, and left colon) was not statistically different either (Fig. 1). The overall successful bowel preparation rate was 96.2% (50/52) in both the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS groups. The successful bowel preparation rate at each segment was not significantly different between groups. The overall perfect bowel preparation (BPPS 9) was achieved in 17.3% (9/52) of the 1 L PEG/Asc group versus 30.8% (16/52) of the OSS group, with no significant difference (p = 0.168) (Fig. 2). The perfect preparation rate for each segment was not significantly different between the groups. The overall ADR was non-inferior in the 1 L PEG/Asc compared to the OSS group (55.8% vs. 61.5%, p = 0.691).

Complete purgative ingestion was reported in 98.1% (51/52) of patients in both the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS groups. The reasons for failure were the taste of the agents and nausea in the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS group, respectively. Satisfaction score regarding taste (5.9 ┬▒ 2.0 vs. 6.3 ┬▒ 1.8, p = 0.255), total amount ingested (7.4 ┬▒ 1.6 vs. 7.0 ┬▒ 1.9, p = 0.314), and overall feeling (7.0 ┬▒1.7 vs. 7.6 ┬▒ 1.7, p = 0.096) were not significantly different between groups. The proportion of patients with good (VAS 7ŌĆō8) or very good (VAS 9ŌĆō10) taste, total amount ingested, and overall satisfaction were not significantly different. Both groups of patients showed a willingness to repeat the same purgatives at the next examination in > 80% of cases (p > 0.999) (Table 2).

Adverse events of moderate or higher severity occurred in 16 cases of 1 L PEG/Asc and 10 cases in the OSS group. In 1 L PEG/Asc, thirst was the most common (nine cases), followed by nausea (seven cases). In the OSS group, abdominal distension (six cases) was the most common, followed by nausea (four cases). The frequency of adverse events was not significantly different between groups (Table 3). No serious adverse events or deaths were reported. During colonoscopy, there were no mucosal changes in either group, such as erosion or erythema.

Electrolyte and renal function changes associated with bowel preparation did not occur in the 1 L PEG/Asc group. Although blood urea nitrogen in the OSS group showed a significant numerical change (p = 0.002), it was not considered clinically meaningful because it was below the normal upper range (Table 4). In addition, no clinically significant events were associated with renal function.

We also performed a subgroup analysis according to age (65ŌĆō74 yr, n = 78; 75ŌĆō84 yr, n = 26). There were no significant differences in the successful bowel preparation rate (96.2% vs. 96.2%, p > 0.999) and overall ADR (59.0% vs. 57.7%, p = 0.543) between the subgroups. Additionally, overall satisfaction (65.4% vs. 73.1%, p = 0.630), willingness to repeat (78.2% vs. 92.3%, p = 0.146), and adverse events of moderate or higher severity (25.6% vs. 23.1%, p > 0.999) were not significantly different between the groups.

In addition, we compared age with a cutoff value of 75 years in both the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS groups. There were no significant differences in efficacy (successful bowel preparation rate and overall ADR), tolerability, and safety (complete ingestion rate, taste, amount, overall satisfaction, willingness to repeat, and adverse events) between subjects < and Ōēź 75 in both the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS groups (Table 5).

As the incidence of CRC increases with age, colonoscopy in older adults has increased parallel to life expectancy [17,18]. In general, osmotically balanced 4 L PEG solutions are thought to be the safest, and are preferred in older adults [14]. However, older adults often have difficulties taking large amounts of preparation agents, so they fail to achieve adequate bowel preparation [19]. Fortunately, in addition to 4 L PEG, which is currently considered a conventional standard agent, various low-volume bowel preparation agents such as 2 L PEG/Asc, 1 L PEG/Asc, and non-PEG-based agents such as OSS have been released [19,20]. Several studies have been conducted to compare the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of these agents [8,12,20ŌĆō25]. One of these studies, comparing OSS with 4 L PEG and enrolling patients > 65 years, showed that OSS as low-volume agents was not inferior (in terms of efficacy, safety, and tolerability) to the 4 L PEG [8]. However, this study has a limitation because older adults > 75 years and those with comorbidities were excluded. Another study comparing 1 L PEG/Asc with OSS in patients of all ages showed no significant differences between the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS groups. However, the age of the patients in this study ranged from 20 to 71 years, and most of them were < 65 years [26]. Therefore, we evaluated the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of low-volume preparation agents by comparing both 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS in older adults, including 65 to 84 years and with comorbidities. Our results demonstrated that 1 L PEG/Asc was similarly tolerable, safe, and effective compared to OSS for bowel preparation in older adults.

Our results showed no significant difference in the successful preparation rate between low-volume preparation agents. The preparation scores for each segment were similar in both groups. For proper colonoscopy, the Quality Committee of the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends a minimum standard of Ōēź 90% for adequate bowel preparation [27]. In our study, the overall successful preparation rate by BPPS (Ōēź 6) was 96.2% in both the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS groups.

ADR is considered the primary indicator of mucosal inspection quality and the single most important quality measure in colonoscopy [28]. In our study, the ADR of the 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS groups were 55.8% and 61.5%, respectively, exceeding the target of 25% recommended by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy for screening colonoscopies [29ŌĆō32]. ADR varies depending on the population, purpose of endoscopy, and techniques such as cecal intubation rate, withdrawal time, and bowel preparation level. Thus, every study showed a variable degree of ADR. On average, ADR was higher in studies targeting the elderly than for all age groups. For example, some studies targeting all ages showed ADR from 18.7 to 36.6, and some studies targeting elderly individuals showed ADR from 47.1 to 69.8 [20,22,33ŌĆō35]. Considering the above results, ADR was somewhat higher in our study rather than other studies because we included elderly patients and the incidence of colorectal adenoma increases with age. In addition, since our study included surveillance colonoscopy as well as screening, ADR might be higher than that in other studies.

The satisfaction with taste, total amount ingested, and overall feeling showed no significant differences. Bowel preparation-related adverse events were not significantly different between groups. Compared with previous studies on 1 L PEG/Asc or OSS, the results were similar [8,35]. Because both 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS are low-volume agents, there might be no significant differences in tolerability.

We also compared the efficacy, tolerability, and safety between the subgroups by age and found no significant differences. This shows that low-volume agents are also efficient, tolerable, and safe, even in older adults > 75 years.

The reason why we chose OSS as the control group was that it already showed similar efficacy and safety with superior tolerability compared to 4 L PEG in a previous study in older adults [8]. So, we assumed that it could be a good alternative to 4 L PEG as a preparation agent in older adults if 1 L PEG/Asc was not inferior to OSS.

Our study had several limitations. First, since uncontrolled comorbidities such as severe heart failure, renal failure, and acute myocardial infarction were excluded due to a lack of safety assurance, our results regarding the efficacy and safety of 1 L PEG/Asc were not applicable to older adults with these comorbidities. Additional research should be conducted on older adults with severe comorbidities and structural changes. Second, when the medical staff provided education on diet control and medication regimen before the test, there might have been differences in the patientŌĆÖs acquisition level or reflection of the educational content because our study population was > 65 years old. To reduce this difference, we used the same diet leaflet in all participating hospitals. Third, because a considerable number of subjects had at least one type of comorbidity and took medication, they could be one of confounding factors. Fourth, although the minimum number of samples for each group to obtain appropriate results was satisfied, the number of patients older than 75 years was too small. Therefore, we need more study with larger number of patients in this age group. Lastly, we could not exclude the possibility of inter-observer variability in the assessment of the preparation efficacy. To reduce inter-observer variability, all participating endoscopists were trained with captured colonoscopy sample images before study initiation. We reported the preparation score as soon as the colonoscopy was finished in a case report form, at which a standard image was presented for the standardized assessment.

Despite these limitations, our study has several strengths in that we targeted elderly patients up to the age of 84 years compared with a previous study that included patients aged < 75 years [8,26]. And this is the first study comparing 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS in only elderly patients. In addition, it is significant that the elderly group aged 65 to 84 was classified into subgroups (< and > 75 yr), and the efficacy and safety were compared again. By using OSS, whose efficacy and safety have been confirmed in previous studies, as a comparison group, our study confirmed the results of a previous study. While most of the previous studies usually compared high volume agents and novel low-volume agents, our study is meaningful in that we compared novel low-volume agents against each other in elderly subjects.

In conclusion, both 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS showed acceptable preparation efficacy and safety with high tolerability in patients older than 65 years. Based on these results, 1 L PEG/Asc could be considered as an alternative to 4 L PEG in the older adults.

1. This is a prospective randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy, safety and tolerability of 1 L of PEG/ACs in older adults by comparing it with OSS.

2. Both 1 L PEG/Asc and OSS showed acceptable preparation efficacy and safety with high tolerability in patients older than 65 years. Based on these results, 1 L PEG/Asc could be considered as an alternative to 4 L PEG in the older adults.

Notes

CRedit authorship contributions

Ki Young Lim: data curation, formal analysis, writing - original draft; Kyeong Ok Kim: conceptualization, formal analysis, writing - review & editing, funding acquisition; Eun Young Kim: data curation, methodology, project administration; Yoo Jin Lee: data curation, methodology, visualization; Byung Ik Jang: data curation, formal analysis, methodology; Sung Kook Kim: data curation, formal analysis, visualization; Chang Heon Yang: data curation, formal analysis, methodology

Figure┬Ā1

BBPS at each segment. BBPS, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale; OSS, oral sulfate solution; PEG/Asc, polyethylene glycol/ascorbic acid.

Figure┬Ā2

Efficacy of bowel preparation using the BBPS. BBPS, Boston Bowel Preparation Scale; OSS, oral sulfate solution; PEG/Asc, polyethylene glycol/ascorbic acid.

Table┬Ā1

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Table┬Ā2

Tolerability

Table┬Ā3

Comparison of adverse events in moderate to severe degree

Table┬Ā4

Changes in renal function and serum electrolyte levels

Table┬Ā5

Comparison of efficacy and safety by age in each group

REFERENCES

1. L├Ėberg M, Kalager M, Holme ├ś, Hoff G, Adami HO, Bretthauer M. Long-term colorectal-cancer mortality after adenoma removal. N Engl J Med 2014;371:799ŌĆō807.

2. Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, et al. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1095ŌĆō1105.

3. Cha JM, Kozarek RA, La Selva D, et al. Risks and benefits of colonoscopy in patients 90 years or older, compared with younger patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:80ŌĆō86e1.

4. Loffeld RJ, Liberov B, Dekkers PE. Yearly diagnostic yield of colonoscopy in patients age 80 years or older, with a special interest in colorectal cancer. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012;12:298ŌĆō303.

5. Hassan C, Fuccio L, Bruno M, et al. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:501ŌĆō506.

6. Yang HJ, Park SK, Kim JH, et al. Randomized trial comparing oral sulfate solution with 4-L polyethylene glycol administered in a split dose as preparation for colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;32:12ŌĆō18.

7. Cesaro P, Hassan C, Spada C, Petruzziello L, Vitale G, Costamagna G. A new low-volume isosmotic polyethylene glycol solution plus bisacodyl versus split-dose 4 L polyethylene glycol for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy: a randomised controlled trial. Dig Liver Dis 2013;45:23ŌĆō27.

8. Kwak MS, Cha JM, Yang HJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of low-volume preparation in the elderly: oral sulfate solution on the day before and split-dose regimens (SEE SAFE) study. Gut Liver 2019;13:176ŌĆō182.

9. Zorzi M, Valiante F, German├Ā B, et al. TriVeP Working Group. Comparison between different colon cleansing products for screening colonoscopy. A noninferiority trial in population-based screening programs in Italy. Endoscopy 2016;48:223ŌĆō231.

10. Pisera M, Franczyk R, Wieszczy P, et al. The impact of low-versus standard-volume bowel preparation on participation in primary screening colonoscopy: a randomized health services study. Endoscopy 2019;51:227ŌĆō236.

11. Rex DK, Di Palma JA, Rodriguez R, McGowan J, Cleveland M. A randomized clinical study comparing reduced-volume oral sulfate solution with standard 4-liter sulfate-free electrolyte lavage solution as preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:328ŌĆō336.

12. Spada C, Cesaro P, Bazzoli F, et al. Evaluation of Clensia┬«, a new low-volume PEG bowel preparation in colonoscopy: Multicentre randomized controlled trial versus 4L PEG. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:651ŌĆō656.

13. Moon CM, Park DI, Choe YG, et al. Randomized trial of 2-L polyethylene glycol + ascorbic acid versus 4-L polyethylene glycol as bowel cleansing for colonoscopy in an optimal setting. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;29:1223ŌĆō1228.

14. Hassan C, Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, et al. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy 2013;45:142ŌĆō150.

15. Calderwood AH, Schroy PC 3rd, Lieberman DA, Logan JR, Zurfluh M, Jacobson BC. Boston Bowel Preparation Scale scores provide a standardized definition of adequate for describing bowel cleanliness. Gastrointest Endosc 2014;80:269ŌĆō276.

16. Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc 2009;69:620ŌĆō625.

17. Cha JM. Would you recommend screening colonoscopy for the very elderly? Intest Res 2014;12:275ŌĆō280.

18. Travis AC, Pievsky D, Saltzman JR. Endoscopy in the elderly. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1495ŌĆō1501quiz 1494, 1502.

19. Cohen LB, Sanyal SM, Von Althann C, et al. Clinical trial: 2-L polyethylene glycol-based lavage solutions for colonoscopy preparation - a randomized, single-blind study of two formulations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:637ŌĆō644.

20. Bisschops R, Manning J, Clayton LB, Ng Kwet Shing R, ├ülvarez-Gonz├Īlez M. MORA Study Group. Colon cleansing efficacy and safety with 1 L NER1006 versus 2 L polyethylene glycol + ascorbate: a randomized phase 3 trial. Endoscopy 2019;51:60ŌĆō72.

21. Marmo R, Rotondano G, Riccio G, et al. Effective bowel cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized study of split-dosage versus non-split dosage regimens of high-volume versus low-volume polyethylene glycol solutions. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:313ŌĆō320.

22. DeMicco MP, Clayton LB, Pilot J, Epstein MS. NOCT Study Group. Novel 1 L polyethylene glycol-based bowel preparation NER1006 for overall and right-sided colon cleansing: a randomized controlled phase 3 trial versus trisulfate. Gastrointest Endosc 2018;87:677ŌĆō687e3.

23. Malik P, Balaban DH, Thompson WO, Galt DJ. Randomized study comparing two regimens of oral sodium phosphates solution versus low-dose polyethylene glycol and bisacodyl. Dig Dis Sci 2009;54:833ŌĆō841.

24. Corporaal S, Kleibeuker JH, Koornstra JJ. Low-volume PEG plus ascorbic acid versus high-volume PEG as bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol 2010;45:1380ŌĆō1386.

25. Pontone S, Angelini R, Standoli M, et al. Low-volume plus ascorbic acid vs high-volume plus simethicone bowel preparation before colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4689ŌĆō4695.

26. Woo JH, Koo HS, Kim DS, Shin JE, Jung Y, Huh KC. Evaluation of the efficacy of 1 L polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid and an oral sodium sulfate solution: a multi-center, prospective randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022;101:e30355.

27. Kaminski MF, Thomas-Gibson S, Bugajski M, et al. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Quality Improvement Initiative. Endoscopy 2017;49:378ŌĆō397.

28. Rex DK, Schoenfeld PS, Cohen J, et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;81:31ŌĆō53.

29. Saito Y, Oka S, Kawamura T, et al. Colonoscopy screening and surveillance guidelines. Dig Endosc 2021;33:486ŌĆō519.

30. Atkin W, Rogers P, Cardwell C, et al. Wide variation in adenoma detection rates at screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastroenterology 2004;126:1247ŌĆō1256.

31. Sanchez W, Harewood GC, Petersen BT. Evaluation of polyp detection in relation to procedure time of screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1941ŌĆō1945.

32. Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2533ŌĆō2541.

33. Jung YS, Lee CK, Eun CS, et al. Low-volume polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid for colonoscopy preparation in elderly patients: a randomized multicenter study. Digestion 2016;94:82ŌĆō91.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print