INTRODUCTION

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic systemic, inflammatory, rheumatic disease affecting primarily the sacroiliac (SI) joints and the skeleton. Other clinical manifestations include peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, and extra-articular organ involvement such as uveitis, aortitis, pericarditis, pulmonary fibrosis, and amyloidosis [1].

Dysphagia related to the musculoskeletal system is encountered frequently in cases such as diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH), acromegaly, hypoparathyroidism, fluorosis, ochronosis, and trauma [2]. However, dysphagia is very rare in AS and can develop due to syndesmophytes. Dysphagia in AS needs to be defined, as it may lead to complications like weight loss and nutritional disorders. Here, we describe a case of dysphagia in AS to raise awareness of this condition.

CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old male, who was being followed up for AS, visited our hospital complaining of progressive dysphagia. Difficulty swallowing solid foods started ~4 years prior, and for the last year, he suffered from dysphagia when swallowing both solid and liquid foods. The patient had no pain while swallowing, but did experience coughing, and had lost ~16 kg in the last 4 years.

Upon physical examination, cervical motion was limited in all directions; the occiput-wall distance was 12 cm and chin-manubrium sterni distance was 7 cm. The patient had dorsal kyphosis with a Schober test score of 1 cm. A SI compression test was bilaterally positive; the Bath AS disease activity index was 4.7; and Bath AS functional index was 3.9. Laboratory tests showed that the whole blood count was within normal limits. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 25 mm/hour, and C-reactive protein was 19.8 mg/L (normal range, ≤ 5). Blood levels of urea, creatinine, transaminases, calcium, and alkaline phosphatase were all within normal limits. While he was negative for antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor, he was positive for HLA-B27.

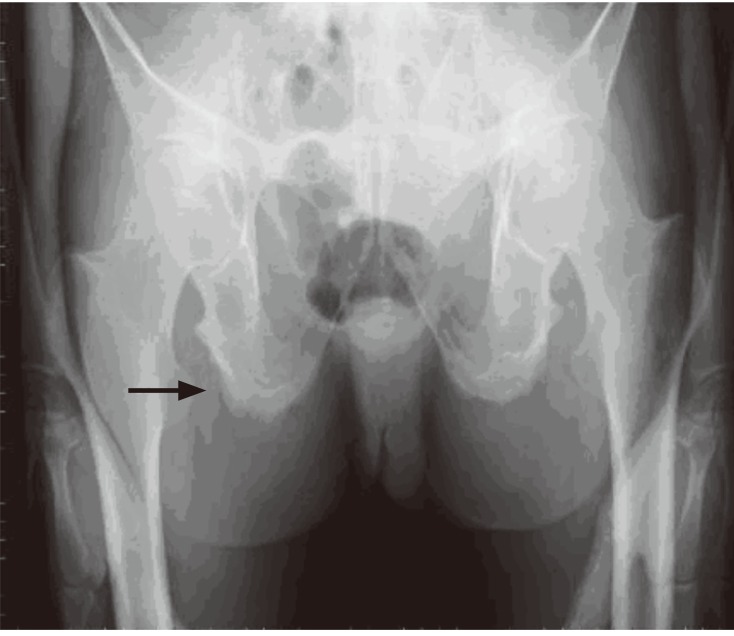

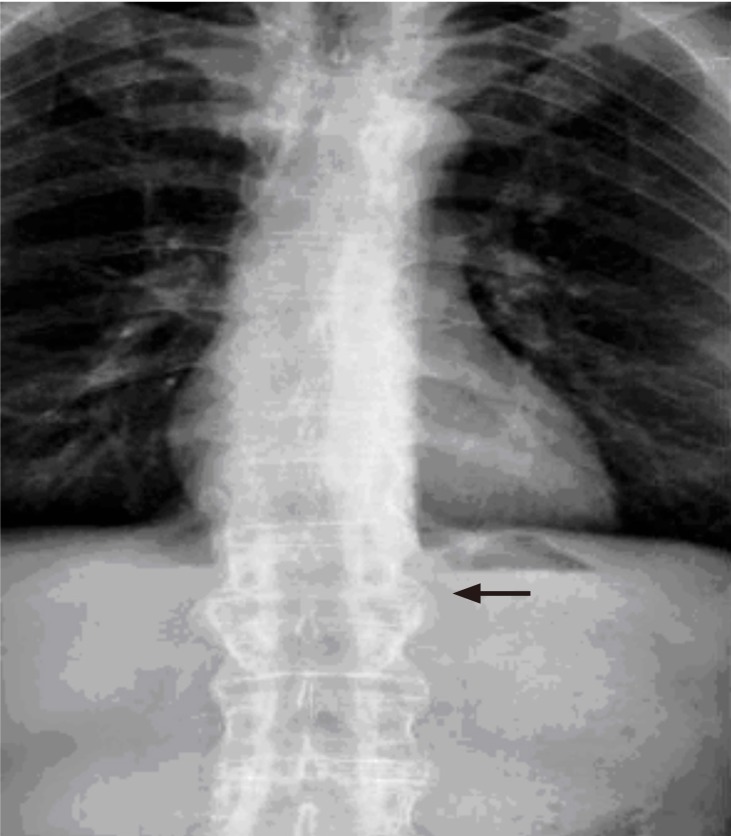

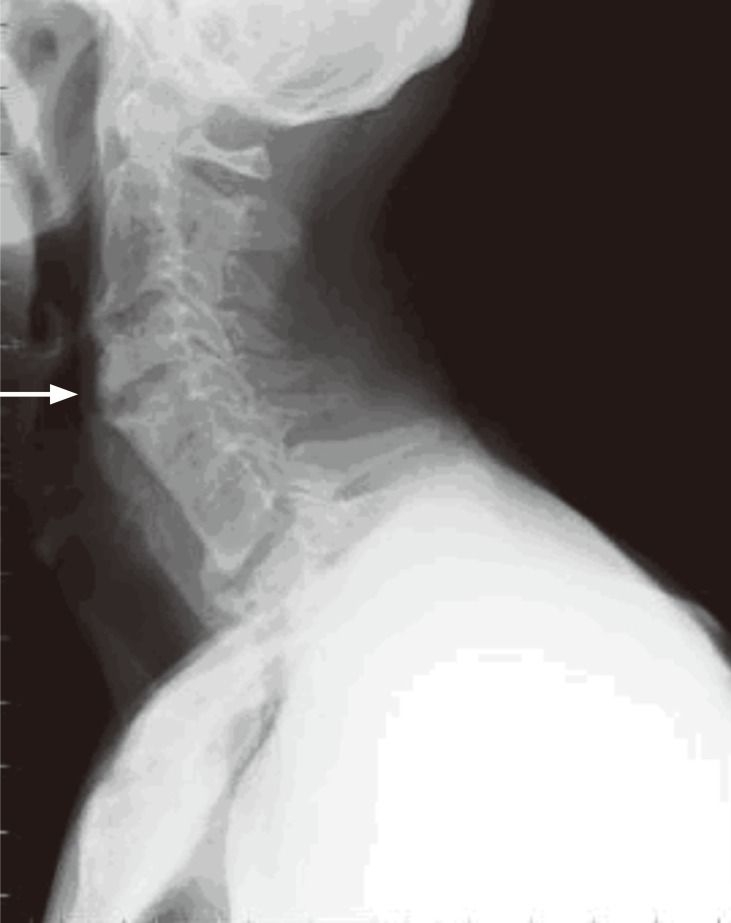

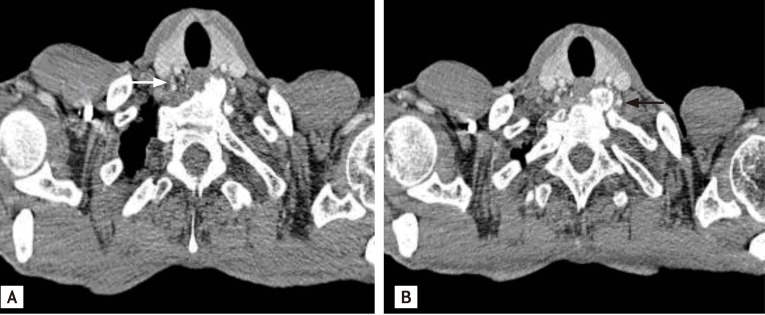

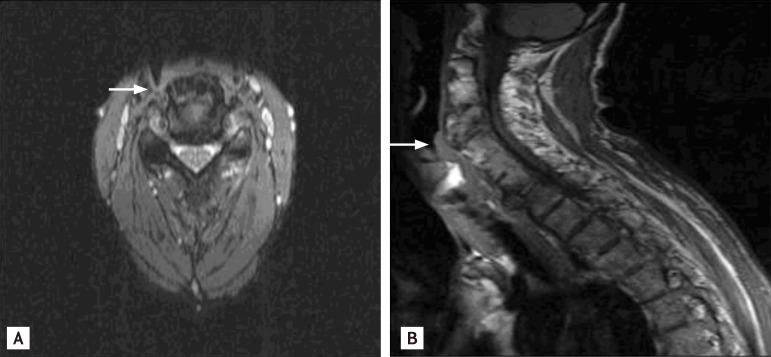

Imaging studies revealed SI joint ankylosis and whiskering sign in pubic bones with simple pelvic radiography (Fig. 1). A bamboo spine appearance was present with simple thoracolumbar radiography (Fig. 2). Osteophytes were observed at the anterior corners of vertebra corpuses at C4-5 and C7-T1 levels with lateral cervical radiography (Fig. 3). Esophagography with barium revealed compression of the esophagus due to osteophytes. Cervical computed tomography, performed to localize the osteophytes and for differential diagnosis, revealed fusion between the C5-C6-C7 corpuses with prominent osteophyte formation anteriorly on the left at the C7-T1 level. This formation compressed the esophagus (Fig. 4). Cervical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to rule out factors originating from soft tissues as causes of dysphagia. A large osteophyte formation on anterior vertebra corpuses at the C7-T1 level, which caused compression on esophagus, was defined in the cervical MRI (Fig. 5).

The patient was diagnosed with severe dysphagia because he could not swallow small solid foods and he complained of coughing when swallowing liquid and solid foods [3]. After consultation with an orthopedic surgeon, an operation for osteophyte excision was proposed, but the patient refused. Diet modification, antireflux and swallowing therapy were prescribed. However, after 6 months, dysphagia had not improved.

DISCUSSION

AS is a systemic anti-inflammatory disease, accompanied frequently by extra-articular involvement [1]. The presence of HLA-B27 has an important role in AS pathogenesis and is often concomitantly observed with environmental factors such as infection [4,5]. AS affects primarily vertebral joints and intervertebral disc distance, where lymphotoxic infiltration causes degeneration in the disc interspaces. Ossification and autofusion progressively follow the erosion of vertebral joints. As a result, characteristic syndesmophyte formation, expansive ankylosis, and radiological bamboo spine appearance develop [6]. In our case, there was a large anterior osteophyte on the cervical vertebra resulting from ossif ication. This osteophyte compressed the esophagus to cause the progressive development of dysphagia.

Early diagnosis and treatment of AS is key to preventing complications, such as compression of adjacent organs by vertebral deformities. Initiation of swallowing therapy in the early phases and a patient treatment plan for AS are equally important since most patients with cervical osteophytes can be managed conservatively [2]. Although dysphagia developed in the case reported here, it was diagnosed after 4 years of detailed anamnesis. As a consequence, the patient did not respond to conservative therapy that included diet modification, swallowing and medical therapy, and the condition progressed to a point that required surgical intervention.

Cervical osteophytes are common but osteophytes causing dysphagia due to compression of esophagus are unusual. Abnormal osteoblast growth or activity in ligamentous regions of bone is the pathogenesis of DISH. The criteria for spinal involvement in DISH includes all of the following criteria: 1) presence of flowing calcification and ossification along the anterolateral aspect of at least four contiguous vertebral bodies, with or without associated localized pointed excrescences at the intervening vertebral body intervertebral disc junctions; 2) presence of relative preservation of intervertebral disc height in the involved vertebral segment and the absence of extensive radiographic changes of degenerative disc disease; and 3) absence of apophyseal joint bony ankylosis and SI joint erosion, sclerosis or intra-articular osseous fusion. The case presented here did not meet the DISH criteria, and involvement of the SI and apophyseal joints was typical for AS.

DISH usually begins after the age of 50, is more common in males, and is associated with endocrine and metabolic syndromes [2]. A similar case reported the coexistence of DISH and AS in a patient that developed lung aspiration due to dysphagia secondary to anterior cervical osteophytes. The patient was elderly at 80 years of age and had osteophytes in the clavicle and shoulders, as well as spinal stenosis due to DISH and the posture and bamboo spine appearance suggesting AS [2]. Our patient had onset of symptoms at age 25, morning stiffness, inflammatory back pain, and a positive family history, which are all suggestive findings for AS. He had no comorbid disease related with DISH.

Large osteophytes in cervical vertebra cause dysphagia through several mechanisms. These include direct compression of the pharynx or esophagus [7], tilt mechanism disorders of normal epiglottis at the laryngeal inlet due to osteophytes at C3-C4 level [8], inflammatory reactions in paraesophageal tissues [9], and cricopharyngeal spasm [10]. In our case, an anterior osteophyte at the C7-T1 vertebrae caused dysphagia by esophageal compression. DISH occasionally causes dysphagia. Typically, osteophytes causing dysphagia are in the C5 cervical interspace [2]. Again, our case had a large osteophyte compressing the esophagus at the C7 cervical interspace, a localization not typical for DISH.

The patient reported here had a typical presentation of dysphagia that started mildly and progressed gradually. Dysphagia is graded as none, mild, or moderate. Mild dysphagia is defined as an abnormal sensation in the pharynx while swallowing solid or liquid foods; moderate dysphagia is defined as difficulty in swallowing of large solid foods, but easy swallowing of small amounts of liquid foods; severe dysphagia is defined as inability to swallow small solid foods or development of cough while swallowing [4]. These classifications can be used to make either medical or surgical treatment decisions. Conservative therapies, like diet modification and swallowing therapy, can be employed in dysphagia of mild and moderate severity; whereas surgical therapy is employed if there is no response to the conservative measures or in cases of severe dysphagia [11]. Indications for surgical therapy in moderate dysphagia are not well described. Some studies advocate surgical intervention in the early phases of moderate dysphagia [12], while others propose surgery to patients who do not respond to medical therapy (i.e., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, myorelaxants, antireflux drugs) [13]. The patient described here had severe dysphagia, indicating surgery according to this classification. However, he refused surgical intervention and diet modification with antireflux and swallowing therapy were prescribed.

In conclusion, anteriorly localized osteophytes in cervical vertebrae may rarely cause dysphagia in AS. Early diagnosis is important for conservative therapy response and should be considered when evaluating patients with AS.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print